I said he was trying to play the ruthless male, not to mention the fascist, just a little too transparently.

I was being sentimental, he said.

Maybe, I said, but I couldn’t express myself properly in this rotten language.

He’d do the expressing for me.

Please, stop acting silly.

Is that what he was doing? he asked.

He could go on acting silly, if he liked.

Did I still know what we were talking about?

Did he?

Péter Nádas: A Book of Memories, Jonathan Cape, London, 1997, 222-223

Prologue

After visiting his solo exhibition in MNAC Bucharest, I met Alex Mirutziu in Cluj-Napoca in his studio at Centrul de Interes in October 2017. He showed me the short film of his latest performance Dignity to the Unsaid, which is, and at the same time is not an homage to the English author and philosopher Iris Murdoch. The video reminded me of the oeuvre of the well-known Hungarian author, Péter Nádas and especially his novel from 1987, A Book of Memories. Nádas examines our emotional states, mindsets, feelings and anxieties with an extraordinary accuracy and sensitivity. He emphasizes and transforms into literature the constant approach to understand what cannot be understood, the irrational, the unsaid as well as an unexplainable mystery of human existence: how can something which didn’t even happen, affect our life in a strange way. These are also the fluid territories that are – in my opinion – the most interesting questions in Mirutziu’s work.

Since his early works, Alex Mirutziu challenges the notion of meaning, representation and language. He examines the often invisible power structures and dynamics which are connected to the different modes of expressing ourselves. In his performances and videos the body and its gestures function as a platform where those things could be expressed which otherwise (e.g. through language) are not possible. It would be however a misunderstanding to say that language and ratio are opposed to the free bodily expressions in his work; Mirutziu concentrates much more on the relationship between these two terrains and the shifts, passages, collisions and dynamics between verbal and body language, written and oral tradition, finding and losing meaning.

When we are trying to express ourselves, we constantly reveal our incapability of total accuracy – this happens through errors, mistakes, stammered words that appear also in our body movements, gestures. Mixing the different ways through which we communicate and navigate in the world, Mirutziu highlights those talemonger signs – errors, collisions, fragments and confusions – that are impossible to hide, as well as “ordinary” gestures. We hide ourselves behind the construct of language and “appropriate” behavior as well as bodily gestures, but through sudden ruptures, fragments and failures those things that we try to hide often appear. For a better understanding of gestures and movements in Mirutziu’s works, an essay of Giorgio Agamben would serve as a good example. Agamben quotes in Notes on Gesture, Marcus Terentius Varro, ancient Roman poet and philosopher, who differentiated gestures as a third type of action, distinguishing it from acting (agere) and from making (facere). Agamben summarizes the paradoxicality of gestures in an interesting way: “What characterizes gesture is that in it nothing is being produced or acted but rather something is being endured and supported. (…) The gesture is, in this sense, communication of a communicability. It has precisely nothing to say because what it shows is the being-in-language of human beings as pure mediality. However, because being-in-language is not something that could be said in sentences, the gesture is essentially always a gesture of not being able to figure something out in language (…).” [i] In Mirutziu’s performances we can witness this specific terrain of different levels of communication.

Language and typography as a compass

In his early works Mirutziu experimented with performative-subversive ways of playing with gender roles and stereotypes. These powerful performances (like Feeding the Horses of All Heroes, 2010) already addressed critically the expression of identity through different symbolic structures, what effects global industries and market economy have on our life etc. In his most recent works a shift could be detected: firstly, he stopped “using” his own body and started to delegate his performances. Secondly, from this quite personal starting point he began to focus on questions about the politics of reading and writing and how we constantly reconfigure ourselves through language. What kind of order and security could language give and how do we navigate in it?

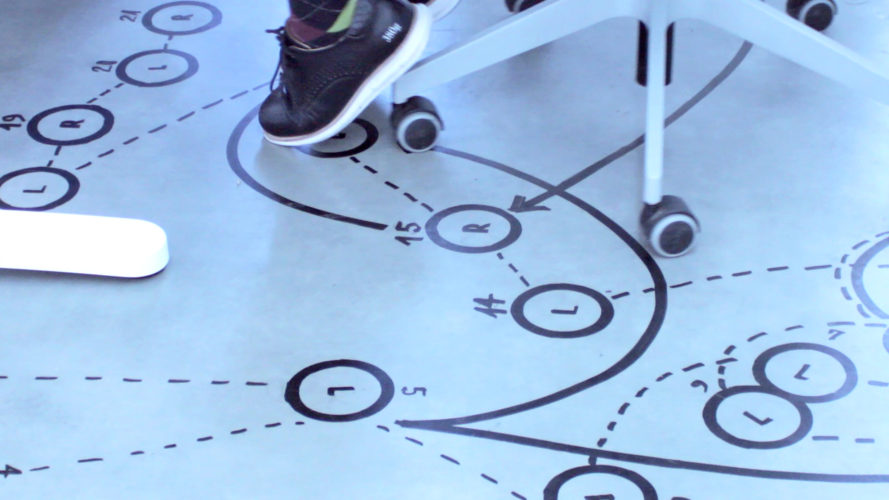

Before analyzing more thoroughly one of the artist’s latest pieces, Dignity to the Unsaid, it is important to mention some of his previous works, in which he focuses more concretely on the notion of design and typography. The artist examines these territories through their relationship with the “user” and tries to highlight the invisible mechanisms, power relations inherent in them. The performance documentation The Finnish Method (2015) focuses on how design – especially the famous Scandinavian one – creates a sense of security as well as functionality, which helps us to find “our place” in the world. Taking the brand Martela as an example, which is known as creator of the “best working environments”, The Finnish Method criticizes in a sense this secure functionality. In the video one can see the artist – at first only his legs, later his hands – as he follows carefully a set of instructions, a step-by-step manual, which seems to illustrate the most effective way to function within this working environment. The ironical performance is in contrast with the act of working itself – instead of doing his “job”, the artist only repeats these movements. The performance raises the question: can these design elements really help us to function better in the world or are these only substitutes for realizing to what extent we are depended on our environment and on outside factors? If every step is regulated, designed, how can we move freely?

The notion of different structures, systems etc. is also important in those performances that put typography, poetry and their translation into dance in focus.[ii] But as a document (2015), which the artist made during his residency in IASPIS – The Swedish Arts Grants Committee, Stockholm, at first looks like an “average” dance piece. However, the work has many layers that open up a complex network of meanings. As I have mentioned earlier, Mirutziu is interested in the politics of reading and writing. More closely he examines how our body takes part in the process of reading (how it is not limited to the mind and the eye), how typography (as an aspect of design) helps us to navigate easier in the world and understand it better. Mirutziu suggests that the fields of poetry and dance, typography and gesture are not so far from each other, as every letter, text, language has its own rhythm, inner logic and basic movement.

For But as a document the artist used the typeface Sweden Sans (created by Söderhavet agency) and transformed its fonts into movements, gestures – thus creating a special kind of choreography. Sweden Sans is not chosen randomly: it is part of the new, national branding of Sweden and according to the designers, this typeface is considered to be the best to represent the country. This way Mirutziu also emphasizes the power relations behind such “casual”, everyday things as fonts and typography. Within the performance, each letter was given a specific set of movements (these instructions were also on display in MNAC Bucharest) and on the video we can see the dancer Pär Andersson performing. What shaped these movements were the movement of the eyes (how your eyes move from left to right while reading) as well as the dynamics of reading (slow, fast etc.) and most importantly as the artist summarizes it: “how we read with our entire body.” As the exhibition text concluded, Mirutziu “transferred from plain page to plain space” the typeface, producing a “live reading” of poems by contemporary Swedish and American poets, Karl Larsson and Graham Foust.[iii]

But (how) do we understand these poems? They appear in a very different sense than reading in a book – we have to decode it while watching the performance / choreography and because of this, the meaning transforms: it becomes fragmented, destabilized, momentary. The moment we grasp it, it disappears. According to my interpretation Mirutziu’s goal was precisely for the viewer not to “understand” the poem through a traditional way – while emphasizing the rhythm and movement in the fonts as well as how eyes are moving while reading – he speaks about a different kind of meaning, understanding, communicating. Yet if we get the fragmented lines: “let your animal mind prevail / and become not as a cage / but as a document”, an enigmatic sentence appears.

This piece also reminds me of the work by Ula Sickle (Canadian artist with Polish origins), which was recently presented in U-jazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art, Warsaw. In the choreographic exhibition Free Gestures (2018) the performers reflected on five short stories, written by contemporary authors about the topic how ideologies become incorporated in our bodies, what is the relationship between everyday gestures and the terrain of politics, activism etc. We can’t understand or put together each story, but we listen to fragments, look at different kinds of constellation of movements, interactions, relations between the performers. Sometimes we notice as a dancer imitates how we scroll on our smartphones or use a touch screen, other occasions we can listen to a monologue in various ways, about punching someone in the face. The audience can participate yet it is clear that their participation won’t change the choreography, which also many times seems to be improvised. The relationship between literature and choreography, gaining and losing meaning, translating words to movements and understanding the different aspects of bodily gestures is what connects the two artists.

Should we talk about what we cannot say?

In one his new works, Dignity to the Unsaid (2017) Mirutziu moves to even more poetical and abstract terrains, to examine the notions of meaning, understanding, memory and forgetting. He abandons the typographical starting point yet still focuses on another figure from literature: the English author and philosopher Iris Murdoch. Both on her oeuvre (which for example in Hungary is not very well-known) as well as how she suffered in her late years from Alzheimer’s disease. Mirutziu is interested in the question: how someone whose primary mode of expression is through writing/speaking deals with the process of fading memory and how this becomes manifest in her public speeches, interviews (and how she reflects on it). As curator, art historian Eugenio Viola summarized, for Mirutziu “Murdoch becomes an occasion or pretext to construct a story that deals with his recurrent themes: otherness, marginalization, exclusion.” Yet from the works a deep understanding and solidarity towards Murdoch becomes visible, as the artist not only uses her as a starting point but through this, tries to deal with often unsaid, repressed notions. That is why Dignity to the Unsaid becomes one of this strongest works, a performance where the emphasis is on such uncanny questions as how to say things which couldn’t be said, how do we constantly fail in communicating with each other, how despite the fact that language always fails us, we try to hide behind it. The three “word workers” (as the artist calls them) in the performance brings into notion those fractures, errors, mistakes when these notions of “normality” or expressing ourselves properly shatter.

In the enigmatic, fragmented yet perfectly shot video we can see three performers who are walking/dancing in an abandoned building, sometimes talking to each other or to themselves. The texts we can hear are poems, written by Mirutziu inspired by the English author, except the one in the elevator scene, which is constructed form an interview with Murdoch. The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease – confusion, the inability to associate words and concepts – become visible in a subtle way through fragmented gestures, accents, stammering, repetitive movements and the tangling narrative which won’t make a coherent story. Again the essay by Agamben is worth mentioning here, as what he writes about the Tourette syndrome and explains the situation when “catastrophe of the sphere of gestures” arrives. As the philosopher concludes: “patients can neither start nor complete the simplest gestures. If they are able to start a movement, this is interrupted and broken up by shocks lacking any coordination and by tremors that give the impression that the whole musculature is engaged in a dance (chorea) that is completely independent of any ambulatory end.”[iv] The movements of the performers could also remind the viewer about this “catastrophe of the sphere of gestures”, and Agamben’s sensitive comparison between these specific bodily movements and dance is also worth underlining.

The fragmented story parts are telling about sensitive observations and poetic reflections about the day, light, and also about the mind, which again connects Mirutziu’s interest not only to the psychological/emotional aspect, but to the cognitive processes and the “scientific” explanation about what happens when we lose our memories. One of the strongest parts of the film is the scene that takes place in the constantly moving elevator while a red light is shining. In this scene two performers out of three are always “silent” – or as their post-it says: they will be back in x seconds – while the third one is speaking. These are the most coherent parts of the narrative which could be understood as interpretations of the interviews conducted with Murdoch, where the gestures, repetitions are exaggerated in a strange way (as mentioned above). Here the topics are becoming more concrete: the performers speak about dogmas, beliefs, also about language and the fragmentation of the self (“one part of you disapproves to another part of you.”) – thus they seem to appear as three versions of one person.

In the last, powerful scene the performers are marking a starting line. They get into the position, commence the preparation, but they just keep repeating this movement without actually running. This hesitant movement and the delay itself summarizes perfectly that kind of constant incertitude, doubtfulness which characterizes our life in the current moment: whether about deciding on taking a new job, leaving the country or getting into a relationship with someone. The performers yet suggest that there is a way to escape this “blocked” state, stop postponing the start and step out.

Epilogue

As I have already mentioned, the performance reminded me of Péter Nádas’s novel The Book of Memories and especially the storyline set in East-Germany in the 70’s: a sudden yet deep and disturbing love story between a Hungarian and a German man. The narrator describes their first encounter and the weeks that followed, where time disappeared and only the two people mattered. Even though it is one of the most beautiful romances in literature in my opinion, it also tells a lot about communication, understanding and the constant failure to get to know someone truly. Thus I would like to end my essay with a paragraph that is about how two people communicate with each other through language, which is always, essentially, through the body as well.

“We talked, as I say, though it would be more correct to say that we told each other stories, and even that would not be an accurate description of the feverish urging to relate and the eager curiosity to listen to each other’s words with which we tried to complement the contact of our bodies, our constant physical presence in each other, with signs beyond the physical, with the music of spoken sound, with intelligible words, and at the same time to use words to envelop, to obscure the physical relationship; we soliloquized, we gabbed, we inundated each other with words, and inasmuch as speech has a sensual, physical significance in the meaning, we used it to enhance our physical closeness, knowing well that words could only allude to the mind, to what’s beyond the body, for words may be genuine but they can never tell the full story; we kept gabbing away – interminably, insatiably, in the hope that with our chaotic stories we would draw each other into the story of our own bodies (…).”[v]

[i] Giorgo Agamben: Notes on Gesture in: Means Without End: Notes on Politics, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis-London, 2000, 57-59.

[ii] See also the performance: Stay(s) against cofusion, http://www.alexmirutziu.com/performance-documentation/.

[iii] When Andersson performs a letter, that specific letter is written below on the screen in the video work.

[iv] Giorgo Agamben: Notes on Gesture in: Means Without End: Notes on Politics, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis-London, 2000, 51.

[v] Péter Nádas: A Book of Memories, Jonathan Cape, London, 1997, 205-206.

POSTED BY

Flóra Gadó

Flóra Gadó (b. 1989) is a freelance curator, art critic and Ph.D. student. She graduated in 2015 from Eötvös Loránd University with an MA in Art Theory. Currently, she is enrolled in the faculty�...

artportal.hu/

Comments are closed here.