In artistic and literary discourses, Romani people are so often negatively represented. Our stories are frequently appropriated by non-Roma people, and many times the characters presented are stereotypical, falling into the archetype of villains who, by the end of the story, are severely punished. To counteract this narrative, over the last few years my collective Giuvlipen and I have been generating a repertoire of plays that focus on our Roma identity, each one displaying a different worldview of Romani people living in Romania.

As academic Suciu Pavel Cristian describes, the dominant representations of Roma place them in the marginal and/or exotic category, like noble savages or members of an abject race. “Beginning in the fifteenth century, Roma inspired an impressive corpus of visual and literary representations. The striking contrast between this inclusion in art and literature and their social exclusion has no simple explanation,” he writes. “The analysis becomes all the more complicated by the fact that writers who put into circulation idealized images of the Gypsies were often indifferent, at best, if not hostile, at worst, to the real population.”

Theatre has borrowed many of these violent perceptions and has contributed to the reinforcement of stereotypes about Roma, constructing and disseminating negative typologies and archetypes of Romani characters such as the fortune-teller, the thief, and the criminal, as well as romanticized characters like the passionate or rebellious “Gypsy.” These dehumanizing caricatures have been assimilated in public discourse, paving the way for both the rampant cultural appropriation of Romani culture today and the anti-Roma sentiment that has historically plagued European society and continues to rear its ugly head.

As a founding member of the Roma Actor’s Association and Giuvlipen, an independent Roma feminist theatre company based in Romania, I work with fellow artists towards the construction of a full Roma cultural identity while also seeking to dismantle widespread stereotypes.

Despite the fact that Romania has the most developed network of minority theatres in Europe—the country is host to nine Hungarian state theatres, two German ones, and one Jewish one—no theatre space exists for Roma minority, the country’s second largest minority. (Unofficially, Roma are, in fact, Romania’s largest ethnic minority, but, given the deeply seated stigma surrounding Roma identity and thus the shame of self-declaration, these statistics are skewed.) One would think that the long history of Romani persecution in Romania—five centuries of slavery and eleven thousand Roma who perished in the Holocaust—would render the establishment of a Roma theatre a moral obligation of the state.

However, when the Roma Actor’s Association approached cultural authorities to help establish a Roma state theatre, the responses we received time after time were offensive against Roma; they intoned inaccurate stereotypes, arguing that we don’t have a theatrical tradition. But, contrary to widely accepted and false notions that Romani have not cultivated a tradition of theatre art, new research by theatre director Mihai Lukacs shows that Roma slaves laid the foundations of early modern theatre in the Romanian Principalities.

“Once the jesters were integrated into the history of Romanian theatre, their ethnicity and lowly slave status were forgotten, thereby denying the symbolic importance of Roma participation in the construction of a national culture,” writes Lukacs. “The rediscovery of Roma jesters is a gesture of recognition of Roma theatrical tradition, which preceded that of Romanian theatre and deeply influenced it.”

The forgotten tradition of the Roma slave jesters, who for three hundred years were the only performers of the epoch, shows us how their early contribution in the building of a Romanian national culture was erased. Moreover, we learn from Lukacs’ research how the compositions and texts of jesters and lautari (Romani musicians) were the “intellectual property” of the lords who owned them. Therefore, the creations of the Romani cultural slaves were automatically transferred to their owners, meaning Roma themselves received no credit for their artistic work.

Historical events, such as the deportations of Roma to Transnistria under the fascist regime of the Romanian government during the Second World War, thwarted Roma theatre culture, which included troupes, puppetry, and circus arts. In the period that followed the Romani Holocaust, Roma artistic production was completely absent from Romanian theatre, yet examples of Romani cultural appropriation proliferated. The most significant example is the socialist play Rhapsody of the Gypsies by Mircea Ștefănescu, which premiered in 1957 and takes place during the period of Roma slavery. Despite being performed with the accompaniment of a band of Roma musicians, the Romani characters were performed by non-Roma actors.

It wasn’t until 2010 that the long period of invisibility of Roma in theatre came to an end with the appearance of the first Romani theatre production in contemporary Romania. The play, Jekh răt lisăme (A Stormy Night), was an adaptation of a story by the illustrious Romanian playwright, I. L. Caragiale, translated into Romanes (the Romani language) by Romani actor Sorin Sandu, directed by him and another Romani actor, Rudy Moca, and performed and disseminated by professional actors who assumed their Roma ethnicity: Marcel Costea, Zita Moldovan, Sorin-Aurel Sandu, Madalin Mandin, Dragoş Dumitru. Although the show enjoyed immediate success, the reaction from the public wasn’t free from hateful public opinions; some considered it offensive that a play written by Caragiale, a symbol of Romanian national culture, was performed in the Romani language and “appropriated” by a team of Roma artists.

While Jekh răt lisăme is a classic comedy whose subject does not necessarily have a connection with the Roma, the gesture of translating it into Romani language and having it performed by Roma actors became a political statement of de-marginalization of Romani culture and, in particular, of Romani theatre. The fact that the piece inspired negative reactions demonstrates the racism of Romanian society—a society that is comfortable with negative images about Roma found in the media and entertainment industry but unprepared for an affirmative cultural view of the same ethnic group. But for Roma actors, Jekh răt lisăme symbolized a gesture of encouragement to initiate other Romani theatrical productions, as well as a glorious beginning for Romani theatre, which became increasingly “political” in the years to follow.

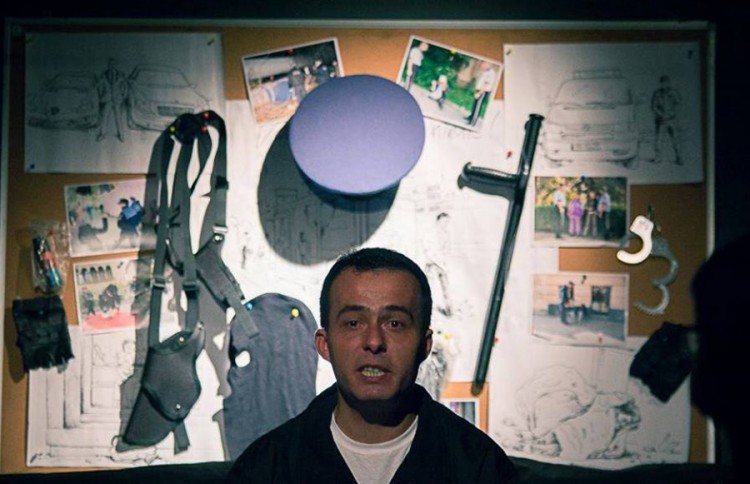

Since that moment, Romania has enjoyed many productions that tackle subjects relating to discrimination and persecution of Roma—plays that directly attack racism (I Declare On My Own Responsibility, a one-woman show with and by Alina Serban about individual discrimination), police abuses against Roma (You Did Not See Anything!, a one-man show with and by Alexandru Fifea about the real story of a young Roma killed by the Romanian police), or bullying, stigma, and the segregation of Roma children in schools (I Am Roma, Too!, directed by Andrei Serban, and Looking Through the Skin, written and directed by Alexandru Berceanu). Other plays depict the forced evictions of entire Roma communities (Without Support by Bogdan Georgescu, and La Harneala, written and directed by me and Lukacs) or early marriages (Del Duma / Talk About Me!, an one-woman feminist show written and performed by me).

Almost all of these plays were built as documentary theatre, using interviews as the basis for the storytelling, and exist in the broader category of social/political theatre. Many of the Romani actors who work in the field have been influenced by the work of director David Schwartz, who calls his artistic practice “political theatre”—theatre that is positioned from and assumes a leftist perspective.

Schwartz believes that all theatre is political because it is public discourse, part of the continuous transformation of power relations in the organization of a society. However, because the idea that art contains an implicit political dimension is still being challenged and minimized in Romania, it is important for Schwartz to explicitly label the theatre he’s making. “Political theatre is a theatre that aims to question, provoke and take uncomfortable positions in relation to dominant discourse,” he explains. “It’s theatre that attempts to attack social and economic issues head-on and to go into the profound analysis of the causes and dynamics of these issues.”

Beyond these definitions, this type of theatre involves artistic responsibility and ethical conduct. In an artistic creation, artists cannot speak authentically and respectfully about race, minority, gender, or sexuality except from a left-wing political perspective. However, there are many productions in Romania that are directly about the Romani experience that are deeply problematic.

Sometimes these productions are documentary theatre, based on true stories about Roma, but are performed by non-Roma actors. They expose intimate parts of Roma’s lives, exploit their suffering, and are not only appropriative in terms of story and costume, but also present stereotypical depictions of Romani people. The plays speak on behalf of the Roma community from a perspective of the privileged white majority and are seen by a majority white audience.

A counter-example in this regard is the play Despre oameni si cartofi (About People and Potatoes) written and directed by one of the most renowned Romanian directors, Radu Afrim. In line with the method of political theater, the author starts by documenting a true story that took place six years ago, namely an accident on the railway track, which led to the death of nine people, most of them from Roma families who would work during the days as potato pickers. The director chooses for the story to be told by non-Roma actors and shows emotional video interviews with family members of the deceased produced during the documentary process. There are images of harsh poverty that expose their intimate part of their life and exploit their suffering in an irresponsible artistic act, although it is obvious that the director’s intention was to inspire emotion and empathy. Moreover, children of the deceased families are included in the play and reduced to the stereotype of Roma dancers, performing popular Roma dances. Although Afrim said on several occasions that he is not interested in political theater, we notice that the themes of his performance (the Roma minority, poverty, the choice to expose real people who have gone through a tragedy, the choice to work with non-Roma actors playing characters Roma) are deeply political, treated with utmost ignorance, without realizing that he is exploiting real people and situations for the benefit of his own artistic piece.

And even if the audiences may be moved to tears, those tears do not change the ingrained racist mentalities that denigrate Roma and reduce them to the status of absolute victims, nor do they change Roma people’s realities.

Even with the best intentions, talking about Roma without Roma—and, specifically, non-Roma actors playing Roma characters—is dangerous and damaging for the Roma artists who occupy a position of marginality and struggle to make their voices heard on local stages. Romani people have a whole history of oppression and silence behind us, such that no non-Romani artist has the right to represent us in their artistic projects without our voices. That approach only helps to preserve the status of marginalization and precariousness of Roma theatre and Roma artists.

For example, both Țiganiada, an adaptation by the classic writer Ioan Budai Deleanu under the direction of Alexandru Dabija at the National Theater in Cluj— as well as the play Maskar (Between)—by the Replika Educational Theater Center on a text by Mihaela Michailov directed by Radu Apostol— ignore the fact that they speak on behalf of the Roma community from a perspective of the privileged white majority.

Perhaps we would have expected a mainstream theater such as the Cluj National Theater to promote a colorful, exotic image about the Roma and to fall victim to cultural appropriation in terms of costumes, but the disappointment comes from the independent Replika Education Theater group, well respected from a political standpoint on the theater scene in Romania and a supporter of Roma rights. Maskar describes itself as a show about the confrontation between a majority’s perception of a minority and the realities faced by the minority, yet it simply ignores the fact that it presents all these things from a non-Roma perspective.

When I founded Giuvlipen with Lukacs and actress Zita Moldovan in 2014, we wanted to respond to these misrepresentations of Romani people and also offer an alternative option to the Roma actors from Romania in order to reclaim our culture. We refused to pigeonhole ourselves in the category of social or activist theatre, as we felt the connotation that came with the label placed primary emphasis on Roma as a social problem rather than on the artistic value of the cultural product. We preferred instead to identify as a “contemporary Roma feminist theatre.” Our goal was to develop our own practice and methods—not to create documentary theatre but to create fiction, to develop a type of experimental Roma theatre with an intersectional and progressive discourse, one that tells stories of empowerment about our Roma identity.

It was the first time a Roma theatre group formed in Romania, consistently assuming the role of producing theatre. Over time we collaborated with the majority of Roma actors in the country, and we now have six productions in our repertoire: Gadjo Dildo, Who Killed Szomna Grancsa?, Orange Blue, Urban Body, Kali Traś / Dark Fear, and The Cult of Personality. With an intersectional, feminist, anti-racist, and queer agenda, Giuvlipen was named by Reuters in 2017 “the vanguard of the Romani revolution in Romania, a counter-attack, through art and activism against centuries of oppression.”

Although a Roma state theatre still does not exist in Romania, one step was made last year when, for the first time, a state theatre joined forces with Giuvlipen to co-produce a Roma show. The piece, Kali Traś, which depicts the Roma Holocaust in Romania, is part of the repertoire of the Jewish State Theatre in Bucharest. In the following years, as we seek to ensure the continuity of Roma theatre productions in the Romanian national space, our intention with Giuvlipen is to collaborate with other state theatres. Our years of experience in the independent scene have taught us that the precariousness and lack of space threatens our sustainability.

Roma theatre in Europe has been consistently marginalized because of the segregation and discrimination of Romani people as a group. We Romani artists are looking to reclaim our place in the world of theatre with our bodies and voices. As professionals, we are interested in using theatre as a way to speak about our experiences, as a response and as recourse to the lack of inclusion and marginalization we have faced. At the same time, we want to get rid of the idea that Roma theatre is sad, overwhelmingly and focused only on our oppressive experiences. We celebrate our identity and resistance through theatre, we take a lot of pride and joy from being Roma on stage and we want to contribute to a new type of drama more inclusive with minorities and non-white theatre makers.

This piece originally appeared on HowlRound.com on 10 March 2019.

POSTED BY

Mihaela Drăgan

Mihaela Drăgan, born in 1986, is an actress and playwright who lives and works in Bucharest and Berlin. In 2014, she founds Giuvlipen Theatre Company, for which she is an actress and playwright, a �...

mihaela-dragan.com/

Comments are closed here.