Christa Wall is an Austrian multidisciplinary artist based in Vienna. With a tentacular way of thinking, Christa touches the space between performance and singing, between ritual and activism, between folk culture and queerness. Her works invite us to become complicit in cultivating storytelling of responsibility, unraveling aqueous poetic soundings and luring chants composed by tender bodies.

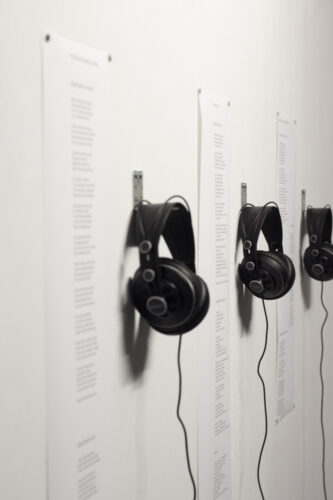

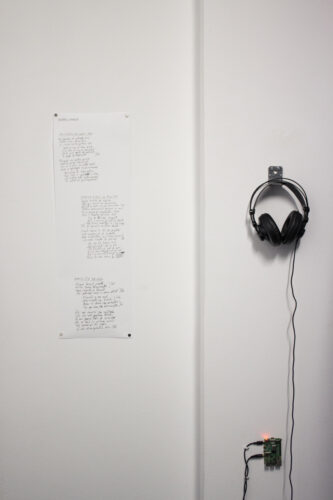

Wall and myself engage in a dialogue about their art practices and the common interest in the mourning ritual, offering an introduction to our show From Tears to Ideas, which was on view at Atelier 35 from the 15th of November until the 15th of December 2021. From Tears to Ideas is an act of grief performed in a world in ruins that undergoes various crises and an ongoing pandemic. Through the mourning ritual, one can connect with an individual and collective body, vulnerable and permeable, while searching for alternative ways of care, affection, and solidarity.

Andreea Vlăduț: When did you first become interested in folk customs?

Christa Wall: My interest in folk customs blossomed while researching yodelling, a powerful and striking voice technique. I dived into the subject in 2015, when I started to become more interested in folk dances and rites of passage, particularly in the process of warding off evil spirits. There was a mixture of thinking about mythology and magic, a focus on the processes of metamorphosis of humans and animals, rituals embodying creatures with beyond-human features.

A.V.: Can you tell me a bit more about some of your works related to folk customs?

C.W.: Iridescent Iteration is one of the main performances concentrating on the subject of alpine folk customs, a 2018 project in collaboration with artist-performer Bernadette Leinbauer. We recreated a ritual centered on the reinterpretation and transformation – a feminist appropriation – of yodelling and Schuhplattler dance.

What about you, Andreea? What sparked your interest in folk customs?

A.V.: Before I started this project about professional mourning, I had made one performance piece together with Florine Mougel. We reenacted Taranta, an Italian ritual, through a noisy and distorted audio-visual performance.

I started more in-depth research about folk customs, focusing on the topic of moirologists, as a result of my grandmother’s biography. At my grandfather’s funeral, I discovered that she was a professional mourner. The image of her and two other mourners next to my grandfather’s coffin got stuck in my mind. She wailed for three days and she continued doing so for the next 40 days after the funeral. I found the entire ritual very touching, the piece in itself: few lyrics, emphasis being put on the words through repetition and gestures.

I have also become interested in the non-linguistic aspects of mourning: body movements, gestures, the poetical and physical language that is born out of grief.

C.W.: How did we start the project?

A.V.: I started the project by documenting the biography of my grandmother and collecting her stories. Then I compared various laments from Romania with the laments from Greek tragedies, beginning with their structure and form. Furthermore, it was very important for me to emphasize the feminist aspects of the performative act of grief.

We started our collaboration based on creating electronic music in 2020, by combining an interpretation of classical and improvised lyrics of laments with electronic DIY instruments. To sum it, I would say that our piece is a reenactment of the ritual through voice and electronic music, highlighting the importance of laments and mourning rituals in times of urgency and deep environmental destruction when one is overcome with loss and grief.

Our research began with a theoretical input on the profession of mourning and the funeral rituals from different socio-politico-geographical contexts throughout history, as well as on the politics of grief.

C.W.: We also aim to create a space that opens up to the understanding of how to cope and engage with grief. Grief has the potential to transform itself into power and even empowering acts can help us nurture community and resilience.

A.V.: Pursuing this further, we started to explore and study in detail the gestures and the body expressions of the mourning ritual. Even though the traditional Romanian ritual in itself has an instant impact and is very straightforward, your interpretation builds on the opposite, slow-motion and stillness.

C.W.: That’s true. By slowing down the movement, I underline the time it takes to cope with grief. It is a process that needs a lot of slowness and a feeling of safety to be able to access and involve the somatic memory of our body on how to mourn.

If we manage to create a brave space for vulnerability and if we allow it, our body knows how to express grief through movements, gestures, and voice expression (pitch, tone, timbre).

Our research wasn’t only based on anthropological, historical books and articles, but also on some specific artworks, which explore the visual poetry of gestures and the importance of repetition and stillness. We got inspired by artworks such as Gestures by Hannah Wilke, Repair and Restore by Ekin Bernay, Maria Hassabi’s Staging, Gisèle Vienne’s Crowd, Bill Viola’s The Quintet of the Astonished.

A.V.: What kind of vocal technique are you using? And why are you using this technique in the context of mourning?

C.W.: I am using the technique of yodelling. For me, it is an utterance that comes from deep within you, a calling to communicate with people, animals, and maybe also your ancestors. In terms of vocal technique, it is a focus on, or an exaggeration of, the audible change between the head and the chest register, which usually gets avoided in a lot of classical western singing techniques. You find it in a lot of traditional folk vocal singing styles, in different variations. In our piece, I highlight this in-between space. This tool becomes the main characteristic of the vocal style.

First of all, breathing is circulation, an extension of our body reminding us of our kinship with forest on land and the underwater. It is a very powerful tool to calm our nervous system, and it is rhythm. It is also seen as a messenger of the soul. And when it comes to laments, it is one of the most important tools of expression.

For the listener, it creates an immersive space through the sensation of circularity. Working with the breath is a practice and it is also essential to the ritual of mourning, which invites grounding in order to slow down, to allow vulnerability, and to open up space for various cries of pain and grief. Aisha Devi points to the impact and the healing power of various frequencies and vibrations on our body and mind. She also says that the base frequencies connect with the lower parts of the body.

A particular instrument that we use in the performance of Pneuma Lamentare is toaca.

Can you tell me about the history behind it and what was the reason for using it in the first place?

A.V.: One informs the others that someone from the community has died by sending out particular sound signals – by either beating the wooden toaca or by ringing the church bells. Ion Ghinoiu describes the instrument, drawing on its history, in his book Cartea Românească a Morților (The Romanian Book of the Dead). From my point of view, the sound of the toaca in the composition is a key transition element in the performance, which marks the progression from stillness to the powerful sounds of the beats and voice.

C.W.: Can you introduce us to the other instruments you built for the sound piece?

A.V.: I used DIY instruments for the composition. One of them is a huge spring instrument that sounds like a cello. I play this instrument by using a head massager that generates a continuous movement of the spring through its vibration. The uninterrupted motion and the metallic sound generated by its materiality create overtones, distortion, and harmony.

The bow box is an instrument with many steel wire springs of different thicknesses screwed onto a wooden box. A piezo is attached to the bottom of the box, which is plugged to a delay effect. I play this instrument with a violin bow, aiming to achieve various tonalities and overtones due to the different materialities, thickness, and varying pressure of the bow strokes. In the composition, this instrument is combined with continuous breathing. As a result, the two specific sounds merge and the listener can’t distinguish the instrument from the human voice.

The spring guitar was constructed by assembling found metallic objects, springs, strings, etc. I chose to play this instrument to get accents in the musical composition, getting the same beat of the toaca.

The Techno Beats

We chose to explore the possibilities of electronic music in our piece. The transition from the serenity and introspective part to the powerful techno beats and the variety of frequency ranges were of special interest for us because of the impact it has on the body.

The ritualistic space and how it invites processes of collective transformation in times of uncertainty

C.W.: Mourning as a collective practice is a tool of resistance to the current world situation. Understanding the significance and the therapeutic power of grief is essential in coping with loss. Through the ritual of mourning, we can also reflect on the societal restrictions which shape our emotions, especially in the public sphere and beyond it. It can also provide an alternative to a sanitized or eerie view on death. Mourning is a social and cultural practice and process that teaches us to accommodate the loss. That is the reason why we started to wonder if mourning takes on a central part in our attitude towards the various crises and the ongoing pandemic we are experiencing could it enhance our engagement with the world? Could it break again the barriers between the self and the other (be it human or nonhuman)?

From Tears to Ideas project was realized in collaboration with Teodora Manolache, Ioana Mutu, Dorel Langă, Morunglav Taraf, and Daria Nedelcu.

The project was funded by the Austrian Cultural Forum within the program #newTogether.

POSTED BY

Andreea Vlăduț

Andreea Vlăduț is a Romanian multimedia artist based in Bucharest and Linz, Austria. She brings to the foreground raw, unaltered sounds of the environment, overlapping them with video images or filt...

andreeavladut.com/

Comments are closed here.