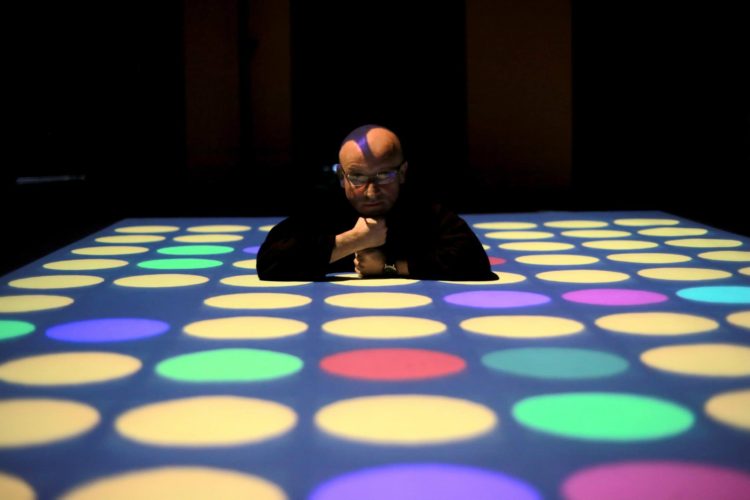

Experimental musician Cătălin Crețu, who likes to play a lot with technology, often performatively, has a special relation with his computer. He tempers it better than a clavier, he tames it, communicates with it. But he also loves acoustic sound, which he modifies with software, sometimes connecting a laptop to a grand piano. As a researcher at the National University of Music, he has written numerous times on the processes of the sounds he makes, having also recently published the book 3logia, a collection of articles that might seem technical at a first glance but, in fact, flow with metaphor and are accessible, language-wise, even to the layperson. Crețu’s relation with technology is a special one, which draws only a fine line between analog (acoustic) and digital (processed, numeric).

The artist likes to often employ a visual, sometimes almost tactile dimension to his sound pieces, using projections, lights, and interactions with augmented reality. Crețu is a great fan of controlled randomness, where the computer has many ways of sculpturally modifying the sound, within pre-set parameters. He programs his own software and uses apps on his tablet, in addition to his synthesizers. He works with all kinds of sensors and contact microphones to capture acoustic sound or, for instance, the brain’s activity in real time.

The “musical” interaction between the human body and technology begins in the ’90s, when Crețu attended the Universities of Petroșani (electromechanical engineering) and Timișoara (music) in parallel, and in 1998 graduated from the National University of Music in Bucharest. This was followed by Erasmus and New Europe College scholarships and specializations, masters and doctorates in multimedia composition or spectral music and a growing number of live appearances in the most varied contexts: from the ARCUB stage to independent galleries or the Innersound festival. His work is a hallmark for sound experimentation with both synthesizers and neural headphones or different types of sensors, all through modules programmed by the artist himself. Most of Cătălin Creţu’s performances bring something new to the field of interactive music and not just locally, inventiveness being the key word here.

There is a lot of ground to cover in Cătălin Crețu’s career, from his first encounter with a computer capable of “making music” to his experiments with neural headsets, which I attempt to do in the interview below:

When did you first feel you could truly communicate with your computer and faithfully transpose your ideas to it? How did your first encounter with a computer able to “make” music look like?

The moment I truly began communicating with my computer was when I learned its language and it became my receiver, the decoder of my messages, and a giver of feedback. From then on, we have been interfacing with each other. My first encounter with a computer capable of making music was at the Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg in 2001, as part of a year-long in-depth study program with an Erasmus grant. It is then that I used audio editing programs and had the opportunity to get a sense of the electronic medium’s musical potential.

Before Max, the multimedia-focused programming language, what did you use to communicate with your computer?

I used Pure Data (Max’s precursor), scripting languages like Csound or SuperCollider, or software from IRCAM Paris: Modalys, AudioSculpt, OpenMusic, etc. Today, Max’s platform offers me all the instruments I need to develop any project, and that is why I remain faithful to it.

I’ve seen you many times augmenting pianos through tech. What do you like to use best when you “break the sound” of a piano, from ping-pong balls to contact microphones or sensors?

I love acoustic-electronic hybrid sounds. That is why I often augment pianos through bicephalic preparation, using various means to expand its normal timbre. In my works Piano Interactions I & II, I used three entities simultaneously in what I call double acoustic schizophrenia: the real piano, a sampled piano, and a microphone-processor system, the last two coming from speakers placed close to the piano itself. The performer-pianist is the one who controls sound processes through various kinds of sensors, through actions strictly notated on the score, and with the help of the computer, the mediator of the duet.

What are your favorite pieces of tech/gadgets, besides the Kinect or the Emotiv Epoc EEG headset?

My favorite devices are synthesizers. They satisfy both my “needs”: my artistic one – through their practically limitless offer of timbres – and my technological one – by allowing me to automate and control various sound processes. As an external interactive control instrument, I have been increasingly toying with the iPad.

What do you think about generative music? Don’t you sometimes feel you’re losing control?

I believe some classical pieces can be generative too, in the sense that they develop micro-ideas like a cell or a (sub)motive: Bach’s fugues, Beethoven’s Fifth, etc. In the musical-technological context, I would mention algorithmic composition, a way in which musical works can be formalized in symbolic representations. In this sense we can speak of condensing the compositional process into a series of rules and instructions whose goal is to automate musical labor.

How much is programming and how much is improvisation in your works?

In the works I made using my computer, I often use a technique called controlled randomness. It was acoustically experimented with by Polish composer Witold Lutoslawski. In parts of his scores, he would write a few notes framed in a rectangle, which the performers would play at the rhythm they wanted, improvising them on the spot, the randomness being therefore controlled. When I work algorithmically, I leave the computer the freedom to choose certain development paths, of course within my set of limits. I thereby generate classes of compositions, a term I borrowed from set theory.

How do traditionalist musicians, used to scores and conductors, react when they come into contact with the Center for Electroacoustic Music and Multimedia at the National University of Music in Bucharest and the possibilities of expanding the classical vision of music?

I will answer with an example. As part of the post-doctoral project MIDAS, undertaken at the National University of Music in Bucharest in 2012, I developed a project for a piano augmented with sensors, the one mentioned earlier. The experts, my classically trained university professors, were very open to my proposal. The fact that I did everything I could to dissect the technological processes and translate them in as classical terms as possible probably also helped. For instance, I produced a score on which I wrote both the notes that the musician would play, as well as how the sensors would have to be activated and, depending on the case, the effects obtained. I personally take every opportunity to talk about the activities behind my multimedia projects. I do it gladly. I believe that is how we can avoid a gap between worlds.

When composing, what “creative-alchemical” recipes do you use, as you mention in your recent book 3logia? What is your approach?

I used the phrase “urban alchemy” to name a multimedia project with an apocalyptic vision, a critique of the dark side of technology, using artistic means to draw attention to a potential scenario: the city dweller exists no longer, their place has been taken by a shadow, their being has melted into a form devoid of content, a transparent entity through which urban reflexes pass intermittently. It is a confirmation of technology’s failure on the human level, as the human remains only as an illusory, virtual form, an outline, a silhouette.

You talk about a certain religiosity in your relation to artificial intelligence. How do you think the future will look like: will we become 100% dependent on it or will it just augment our sensory experience? Is artificial intelligence a new religion?

Artificial intelligence is what we allow it to be. It is a cohabitation that can stretch across a spectrum going from mere technological appendix or kitchen appliance to a replacement of our being. Each of us decides what place and bandwidth technology is allowed in our private life. About my spiritual relation to technology, I wrote some time ago in an article the following: “I am friends with my computer. I communicate with him, I am nice to him, I sometimes ask him for advice. Together we established the rules of good technological behavior, we live together, collaborate, I help him be creative, interpret the algorithms I give him honestly, and I even allow him the freedom to complement my own creation, to be my coauthor. We are a team, and even though we interact a lot, we never fight. He is my new interface with the world, my artistic facilitator to a magic, Matrix-type world, a space of freedom and technologically mediated challenge. He is human, I respect him, am faithful to him, and he is loyal to me.”

How do you see the future of music dictated to a computer directly from your brain through EEG? Experiments have advanced a lot, but where do you think it will all go? How do you see the development of brain-machine interfaces?

Given that we possess a rational and an emotional brain, the ways we interact with EEG headsets will be adapted accordingly: the rational conceives algorithms, the emotional tames them. Such interfaces, I believe, have applications in various artistic contexts: in creative or performative processes. I believe the most spectacular potential lies in making music together by linking up multiple brains, a kind of “EEG chamber music.” It would also perhaps be a way in which technology would make up for having estranged humans from each other.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Miron Ghiu

Obsessed by new technologies and a careful manipulator of sounds of all kinds, Miron Ghiu lives in a continuous present. He likes to wallow online and lounge offline, surrounded by as many buttons to ...

mironghiu.wordpress.com

Comments are closed here.