Among the few exhibitions that managed to prevail against the difficult context of the pandemic, between October and November 2020, was Studies of Gaze, an excellent project by GAEP Gallery in Bucharest which brings together a series of heliographs and video works inspired by the Minerva photo archive (of the Cluj-based newspapers Făclia and Igazsag). Răzvan Anton, the project’s author, known for his involvement in the digitization and promotion of this archive, presents a research that goes beyond strictly visual practice, a meta- or pata- discourse (see Alfred Jarry’s pataphysics, which appears on the border between science and poetry, where art is able to access the truth and science becomes critical and self-ironic) interested in new kinds of functions, interpretations, and ways of seeing associated with contemporary art.

What at first glance appears to be a game of revisiting a historical archive (an aesthetically impeccable one), a reconstruction of photographs through a process combining manual labor with technology, turns out to be a relevant research project, with many layers and interpretations, centered around repositioning drawing relative to etching and photography (think of the status of the latter two as reproduction technologies that only later asserted themselves as art forms) in the recent age of post- prefixes (postmodernism, posthumanism, postphotography, postcinema). In this sense, questioning the photographic process in the age of postphotography will have to involve tracing its evolution from the old writing with light to its status of witness to and means of representing (the sometimes traumatic) reality, and also to its status of media affect or tool of the society of the spectacle.

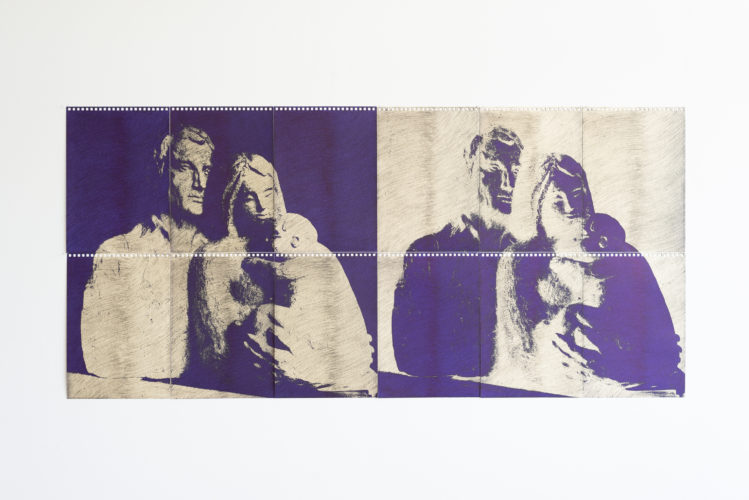

The idea of heliography, of including the sun in the art-making process, becomes in this context a way of initiating an archeology of the photographic process. Răzvan Anton’s heliographs are technically produced by layering a series of masks (negatives of the archive photos about to be recreated) over pages from a notebook hatched in with a blue pen and exposing them to the sun on the studio window. Free to act on the areas not overlapped by an opaque surface, the sun decolorizes the artist’s hatching, creating the image.

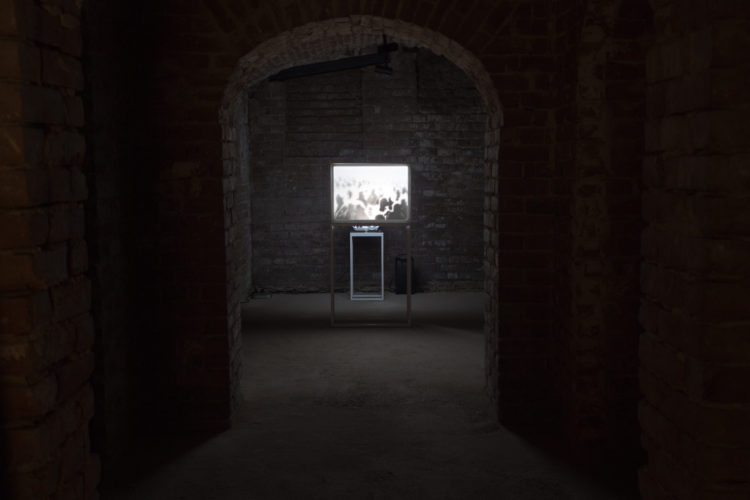

As for the videos, they comprise footage captured by the artist that is reflected onto the studio’s wall with the help of mirrors prepared like engraving plates (the dark areas are covered so as not to reflect light). Each mirror shows a photo from the Minerva archive, one with a strong socio-political message, not chosen at random.

Two other discourse layers comment on the type of gaze engaged by visual art nowadays as well as the status of the art object and the possibility of practicing art in an age marked by functionality (craft, techne), by the multiple conditionings of the market and the inescapable noise of the media, the channels through which the technical image, in Flusser’s words, circulates.

If the technical image is the image produced with the help of an apparatus, the role of the contemporary artist becomes, in Flusser’s view, to overcome the condition of mere operator of said apparatus, delineating a space of freedom that is indispensable to art. Transcending the condition of mere operator comes with asserting your own message, beyond the redundant noise of the apparatus and its manufacturing company (interested only in boosting sales). In the current case, Răzvan Anton’s unique way of working with photography negates both the interference of nationalism, a constant of the Romanian government, regardless of political leaning, and that of technology itself, with its functionalist (non-gaze) blindness and infinite proliferation, insensitive to its consequences on humans and nature.

In this sense, both the artist’s heliographs, produced in collaboration with the sun, and his videos, in which the willow tree’s branches and the birds in front of Anton’s studio window become amateur actors playing an open script, ensure that the technical image (photo, video) is recharged with a certain kind of aura, of authenticity. It seems we are seeing how art practice returns to nature, paradoxically by means of technology.

In my view, we could say that the videos that allow the intervention of ambient elements in the footage of shadows on the studio wall by the artist’s engraved mirrors recontextualize the works of Fluxus and Nam June Paik (the latter’s Electronic Nature series) in a post- age. Because of the almost ritualistic act through which the artist hatches his notebook pages with a blue pen, on which the sun will then apply its writing, the heliographs also reconstruct a neo-avant-garde performance practice. The gesture of hatching is, as Răzvan Anton himself states, a personal gesture of discovering the image, of activating archive photos, of incorporating them in the texture of the present, like the design of a coin is brought into presence by shading a piece of paper placed above it. This gesture is reminiscent of Vija Celmins’s practice of recreating stones found in the Colorado Desert. In other words, the gesture of recreating a stone’s features, spending hours to recreate each freckle, each small imperfection, is, like that of meticulously hatching on paper, loses its proximity to the technical, rushed act of copying. It is closer to the old sense of the term mimseis, that of following nature’s way of creating (rocks are formed, birds sing, the spider weaves a web).

We must also note that, in order to become imprinted, these heliographs need weeks of exposure to sunlight. This kind of patient time, which, following Debord’s thinking, I would oppose to the linear time of the society of the spectacle, dominated by consumption, is an important part of the project. In a posthumanist age, time as duration, the kind of time that is free, qualitative, and financially unquantifiable, seems to be art’s solution in reconsidering nature and the old species of cyclic time (that of the seasons).

The same contemporary posthumanist, postmodern, interdisciplinary paradigm enables a paradoxical revaluing of nature and unquantifiable time by means of technology, as well as a recontextualization of the aura, without losing political relevance. Surprising even Benjamin, Răzvan Anton’s works manage to combine the poetic with socio-political commentary, in a manner similar to contemplative cinema – I am thinking for instance of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s fascinating docu-fiction Mysterious Object at Noon (2000).

One could also argue that Răzvan Anton himself follows the paradigmatic model of the posthumanist artist, embodied by Beuys: an educator concerned with the way their students see art and society and only secondarily a maker of art objects. Being a professor at the University of Arts in Cluj, Răzvan Anton chose, perhaps not by chance, for his exhibition the theme of the gaze engaged by contemporary art, a kind of gaze marked both by its bidirectionality as well as by its ability to critically and responsibly relate to the canons of various paradigms. Studies of Gaze therefore questions one of the biggest problems of Romanian art schools, and that is that they restrict the gaze within a perimeter of forms and techniques that no longer speak to new generations, a car park where none of the vehicles work anymore. Learning a craft for the sake of the craft proves to be, in this context, just as useless as training athletes that do not know in which direction to run. As art becomes a play of gazes (why do you look at something? how can you make others look?), solving this problem will require engaging in an exercise of orienting and recovering attention (the artist’s, the public’s). If we were to invoke the workings of inspired art, the chain of enthusiasm going from muses to artist, performer, and public (Platon, Ion), drawing an audience’s gaze will depend on the artist’s own enthusiasm. Creation returns to its sense of cultivating an interested gaze, which cannot happen in the absence of a strong connection to a subject.

Returning to the problem of canons associated with different historical periods, we notice that the photos from which Răzvan Anton makes his heliographs represent Romanian sculptures from the communist and postcommunist period, united in the same blameworthy nationalist discourse: a bust of Ceaușescu, an anonymous sculpture of a traditional family, an equestrian statue of Transylvanian revolutionary Avram Iancu commissioned in the ’90s, when nationalist politician Gheorghe Funar was the mayor of Cluj.

The monumentality of these sculptures (reminiscent of the typically western obsession with eternity, with everlasting things) breaks down in Studies of Gaze as they are transformed into two-dimensional, almost immaterial compositions that remind one rather of the fragility of Japanese prints and the Zen philosophy of transitoriness, of the author’s withdrawal, of the self dissolving into the world, into nature. The beauty of transitoriness, as the hegemonic position of the self and, implicitly, the author is undermined, is contained under the umbrella of the term to gaze, the only word out of fifty synonyms that became established in contemporary visual art theory and in psychoanalytic film studies.

According to theorist Margret Olin,[i] the widespread use of the verb to gaze in contemporary discourse to mean an attentive, long, deliberate looking at something marks a break between the paradigm of optical, metaphysical, and atemporal visuality and that of tactile, engaged, two-way reception. The shift that took place in the field of art in the mid-20th century, with the neo-avant-garde’s attempt to bring art and life together, saw a corresponding shift in the field of reception. Redefining the artistic process as a socio-political one, close to the field of anthropology, made the loss of the traditional kind of spiritual, elitist gaze (one centered rather on mystery and optical effects than on the relevance of the viewed object) inevitable. A new, dynamic kind of gaze is asserting itself on the art scene, a gaze that, in theorist Jennifer Reinhardt’s[ii] terms, is capable of bridging art and social theory, of integrating politics into the field of art history.

In this sense, gazing means considering the object itself, for itself, passing from optic to haptic, from the atemporal or presentness to presence. Unlike the traditional gaze of the optical, traditional paradigm, unable to transcend the boundaries of the work, this new kind becomes a medium of communication between gazer and gazed-at. It allows the object of the gaze to react, to become a subject, like the characters in Velasquez’s Las Meninas or those in the Farm Security Administration archive documenting the Great Depression.

Awoken from their contemplation, the viewer feels the need to enter into a kind of dialogue with the object of their gaze, which has become a subject. What takes place between the two is a kind of roleplay, a battle of wills (to power). The characters-become-gazers may attempt to seduce each other (like in marketing ads), to give orders (we can think here of the Führer’s presence in Reni Riefenstahl’s films), to ask for empathy (Margret Olin comments on Walker Evens’s famous photo titled Sharecropper’s Wife, in which the woman’s look, reflecting the drama of the Depression, makes it impossible for the viewer to withdraw indifferently, as such withdrawal is revealed as partaking in a politically and economically oppressive system).

In similar fashion, Răzvan Anton’s works, which investigate ways of gazing at and interpreting the Minerva photo archive, encourage the viewer to react and examine. The representation of Ceaușescu’s bust, abstracted until details are lost, becomes the representation of a gesture, of an attitude that can belong to any bust and any (political, administrative, academic, etc.) leader, the message of power itself, of how it imposes and commands. His weakened glance, devoid of power and materiality and reduced to a two-dimensional representation lacking monumentality, questions the artist’s role in revealing social inequalities and the ways in which current totalitarian regimes are imposed and maintained. Its juxtaposition with an equestrian statue commissioned by the administrative-political power of the ’90s raises another topic for discussion: the numerous forms taken by a dangerous nationalist and ethnocentric ideology in Romania over time.

In this sense, studying the gaze becomes studying power, in a sense applicable both to our daily reality and to art. Political power and the power wielded by art institutions functions after similar rules and canons. Foucault’s lesson teaches us about the link between power and knowledge. Benjamin’s lesson, radicalized by Virilio, who introduces terms like the industrialized non-gaze, the entrenched sightless vision, teaches us about the link between technology and perception. Nietzsche’s lesson is about defining art as will to power. Hal Foster’s lesson is to link the gaze’s Dionysian wildness, associated with contemporary art, to a representation of a traumatic reality. In a world plagued by inequality and asymmetrical conflict, Răzvan Anton’s teaches us that revealing the mechanisms of power within the art world encourages critical thinking and can be a step towards a future revealing of broader social phenomena. By innovatively combining history and the present, the virtual and the real, duration and presentness, poetic contemplation with a social message, Studies of Gaze initiates a necessary process of Apollonianly taming the gaze, helping one adapt to a traumatic everyday without obscuring the Dionysian truth of the moment. Transgression (artistic or otherwise) remains possible only once we understand and accept the laws the real, as Bataille advised.

The exhibition Studies of Gaze by Răzvan Anton took place between the 10th of September and the 7th of November 2020 at GAEP gallery.

[i] Olin, Margaret, “Gaze.” In Critical Theories for Art History, ed. Robert Nelson and Richard Shiff. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

[ii] Jennifer Reinhardt, The Gaze, https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/gaze/.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.