The double exhibition I feel something, don’t know what[1] was certainly an event. The project could serve as a template for future national exhibitions. The exhibition was conceived as a collaboration between Zachęta Project Room (ZPR) in Warsaw, an associated space of the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, by curator Magda Kardasz, and the Timișoara-based Art Encounters Foundation by curator Diana Marincu, and succeeded spectacularly in building a creative bridge between Lera Kelemen, Ana Kun, Andreea Medar, Carmen Nicolau, Pusha Petrov & Miki Velciov, Sorina Vazelina – artists active on the Timișoara art scene (a kind of Romanian national team, why not?) – and Polish artists Zofia Gramz, Janusz Łukowicz, Paulina Pankiewicz, Anna Siekierska, Mikołaj Szpaczyński, Marta Węglińska, who have been featured in exhibitions at ZPR. Even the works on display seemed to enter into symbolic dialogues with each other. Communication was carried out playfully on multiple thematic levels: ecosystems and human intrusion, cyborgs, and, last but not least, civic activism.

It so happened that the exhibition in Warsaw coincided with the massive humanitarian crisis on the border of Poland and Belarus, in the Białowieża Forest. Many people trying to follow the fragmented news from the border are feeling something, not knowing what. The government has declared a state of emergency and blocked all access to journalists, medics, and activists into the area. Having become pawns in a large-scale political game, the refugees are trapped between rows of border guards, border police, and razor-wire. They are shoved and pushed back, doesn’t matter if they’re women or children, and left to die of cold, exhaustion, hunger, or thirst. A telling case is that of the 32 people trapped around the village of Usnarz Górny. In other areas along the border, four deaths by hypothermia have been recorded. It is likely that more bodies are still in the Białowieża Forest. The Polish government legalized these pushbacks, which violate the Geneva Convention, post factum. These circumstances demanded of me a certain reading of the exhibition that is more ethical than aesthetic, and which I would like to share with you here.

A new death has just been announced in the area of Białowieża, an Iraqi refugee. This time the cause of death was not hypothermia but a heart attack. At least an ambulance had been called. He died while being resuscitated. It is from the heart that I will start. The symbolic heart of I feel something, don’t know what, powerful and hope-giving, was, in my opinion, Information Age Produces Realistic Fiction, a work by Ana Kun produced in collaboration with fashion designers Gina Larion, Diana Bobar, and Ionela Stratan. It is an installation sewn together from scraps of fabric (surface: 350 x 650 cm) which can take multiple shapes – a volcanic cone, a tent, a flag, a scarf, a bunker’s top side, a bedsheet, a fort, or, as was the case in Warsaw, where it was exhibited in the middle of the gallery, in the passage leading to the basement, a screen covering the curators’ office, continuing the thread of potentially subversive works without interruption.

Information Age Produces Realistic Fiction is, among other things, an object imbued the value produced through the invisible labor of artists – 100 hours of collaborative work, mentioned in the object’s description. I read that the installation was born out of a common feeling of drifting, loneliness, uncertainty, and captivity caused by the pandemic-imposed isolation. In this period, information technology was tasked with filtering interhuman relations, while access to nature and travel opportunities were curtailed. Another source of inspiration was a series of getaways to the disappeared Sumiga volcano, near Timișoara, on the border between Romania and the former Yugoslavia. During the communist regime, bunkers were set up along the border to surveille potential enemies and defend against a possible invasion. They are shaped like natural volcanic cones. Ana Kun & Co transposed this shape in a material that is diametrically opposed to the hardness and oppressive nature of a bunker, using soft colorful fabrics.

Polish border guards see the refugees in Białowieża as enemies or weapons, not as real, suffering human beings, partly and paradoxically because of their clothes, which, some casually say, are too expensive, too fashionable, too good to be worn by some refugees, clothes which they themselves couldn’t afford. Someone once suggested starting a fundraiser to buy a certain border guard a pair of designer label jeans – if a pair of jeans can pull the wool off of his eyes and allow him to see the refugees as people and not hybrid war weapons, why shouldn’t people chip in and buy him one?

The installation’s surface is sprinkled with sewn texts arranged in lines. There is a poem dedicated to a hypothetical female border guard located in a bunker:

“Is this the never-ending informational age where I’m a hunter-gatherer of data, is this my future, hiding in the field of wheat, a bunker’s slit looking at another? / Be the net on the forest floor that will catch the people’s trash, the dying leaves, and the industrious rodents and bugs. / Be the forest rooftop that will catch the lucid dreams, the sun’s radiation, and the dancing plastic bags. / I’m gazing at you, analyzing you, interpreting you, you are what I say you are, for I am everywhere and you are here.”

The artist chose a female figure because at the time of producing her work, the army had employed female civilians to process the information gathered from soldiers deployed along the border (and not only). On the one hand, we are shown a situation of relative gender equality in a field of work generally thought of as “masculine,” but, on the other hand, I am reminded of Julia Kristeva’s texts which warned about women being employed in violent professions. In Kristeva’s view, this carries the risk of reproducing patriarchal structures and violence to the detriment of life-creating and life-nurturing activities. A telling and fresh example did not occur to me. A new death on the border has just been announced, a 16-year-old boy. He had entered Poland from Belarus through Białowieża, then his family was pushed back into the forest. According to his parents, the boy felt sick. His state suddenly took a turn for the worse, and the boy died. The family was forced to abandon his body to protect their other, younger children from freezing. The body has still not been recovered. Perhaps it is on the Belarussian side. Some of the press officers of the Polish border police are women. The press keeps quoting a female major who commented on the case and then the pushing back of a group of minors.

The exhibition’s title was inspired by one of Zofia Gramz’s drawings, which I would read as illustrations of Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”[2] – the cyborg fundamentally stands for partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversion. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely lacking in innocence. No longer structured by the public/private polarity, the cyborg defines a technologized polis based partially on a revolution of social relations within the home itself. Nature and culture are reevaluated; the former can no longer be the resource that the latter appropriates or integrates within itself, and so on. Zofia Gramz’s works seem to be a disavowal of anthropocentrism. The razor-wire in the Białowieża Forest does not only keep unwanted migrants out of Poland but also decimates the ancient inhabitants of the woods – it kills deer who don’t know how to face the lethality of the blades that have sprung up in their paths overnight. The blades slice into bodies and the organs come loose and reunite in new constellations. Gramz’s monsters are also the activists who form autonomous search parties for those lost in the woods, with the help of electronic devices, able to see in the dark, but also the lost ones who manage to survive days on end in the forest, sometimes without food, in temperatures too low to sustain human life.

The cyborgs sketched out by Gramz were joined by Carmen Nicolau’s very elegant, immaculate, gold-accented anthropomorphic ceramic figures with nonhuman heads. The artist questions humans’ dominant place relative to the lives of animals. The figures were inspired by ancient representations of the ancient animal goddess Potnia Theron and her retinue. There is also the Bee Queen, perhaps inspired by Romanian folk tales. But these figures, especially the exceptional and laid-back anthropomorphic sow, but also the two lynxes, which, the artist explained at the opening, are a kind of symbol of Romania, cannot help but create associations with another series of anthropomorphic, but also traumatizing, images, one on display at the same time as the show at Zachęta in another important exhibition space in Warsaw – the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. It is a painting by Wilhelm Sasnal inspired from a scene in Art Spiegelman’s comic Maus.[3] In Maus, the Poles are represented as anthropomorphic pigs. Undoubtedly some of them fell victim to the Nazis, and many Polish names made it to the book of the just, but, on the other hand, some collaborated with the Nazis and took part in crimes against humanity. And what is going on today on the border with Belarus is, formally, terribly similar. Groups of starving, frightened, different people – strangers – appear out of nowhere. Some have money. Some locals feed them, give them warm clothes, and allow them to carry on, but many more immediately report them to the border police. The latter are oblivious to the association I have just outlined. Even though in Poland there are no precedents for being punished for offering humanitarian aid. At the same time, there is an extraordinary activization of the population going on. There are numerous collections of warm clothes, calory-rich foods, hygiene products, money… There are protests in front of the offices of the Polish Red Cross, whose leadership, unlike in its branches in Lithuania and Latvia, is affiliated with state power and refuses to offer aid to the refugees on the Belarus-Poland border.

Paulina Pankiewicz presented 80 small landscapes sketched on pieces of notepad paper. Movement is not only a philosophical practice, but an artistic one as well. The artist is in constant motion. She maps out places symbolically with her entire body, and the abstract lines on the notepad sheets are rather traces of motion and approaches to space than simple landscapes. She assimilates and explores the spatial and temporal coordinates of the environment through her own body. She has gathered the snapshots on display by running around a symbolic place for art history, Mont Sainte-Victoire, obsessively painted by Paul Cézanne. Pankiewicz attempts to capture the essence of art itself. The drawings’ size is comparable to a smartphone screen. This exercise in motion is practiced constantly and by necessity by many people currently wandering through Białowieża Forest. The activists in the organizations currently monitoring the situation at the Polish-Belarus border stated that refugees have sent them screenshots of maps and their location pins, as soon as they thought they were on Polish territory and still had some battery left. Like Pankiewicz, the refugees in Białowieża are in search of a symbolic idea. They are seeking a welcoming land (perhaps Europe?) in which to find peace, shelter, and a future.

In Timișoara, Marta Węglińska exhibited her video The Wolves Prowl, which was absent in Warsaw. It is a story of becoming, a transformation from human to wolf, the construction of a rebellious character, a materialization of the themes that inspire Węglińska: moving around in new geographic and cultural spaces, establishing intercultural dialogues, and initiating mutual understanding. In Poland, the artist exhibited two large-format works. She decided to use watercolor, as it has a minimal environmental impact, but also because it is perhaps the most delicate artistic technique. Delicacy as a topic is also explicit in Andreea Medar’s installation. Węglińska’s watercolors are part of a series of works about close contact – not just physical, but also spiritual and sensual – with the environment. They show the forming of the bond between the perception of human life and the rules governing the cosmos. The watercolors are startlingly beautiful. Perhaps too beautiful for the current circumstances, but we should also remember Dina Gottliebová’s watercolor portraits of Romani inmates in Auschwitz. In Węglińska’s work we see an elegant foot daintily stepping through colors. The work’s description mentions the experiences that lead to the emergence of rituals and beliefs.

The photos by Pusha Petrov and Miki Velciov, Invaziv. Autogenerativ, document thrilling encounters between the artificial and the natural (the curators reference das Unheimliche, a psychoanalytic term often rendered in English as the uncanny). The artists created land art installations that radically altered the space, introducing distorted perceptions and sublime illusions. In their work, the two often start from local histories, plural identities, and cultural singularities. As part of the exhibition, two of their photographs were presented which document two intrusions in different spaces. The first documents an installation created in a forest on the outskirts of Timișoara. The artists implanted plastic straws inside a clearing. Despite being artificial, the straws uncannily imitate nature. The second photo shows an installation of delicate modular structures in an abandoned garden in Timișoara. Human interventions in space are most often violent, destructive, seizing natural resources and claiming possession over territories that belong to other communities or species. In an opposite manner, nature occupies abandoned places slowly, non-aggressively, and healingly. The works resonate with the situation in the virgin Białowieża woods, which abound in artificial objects, razor-wire, silver and golden emergency blankets given haphazardly to the refugees by activists, discarded candy bar wrappers, and torn clothing. The collaboration between Pusha Petrov and Miki Velciov can be discussed as one of many artworks documenting the phenomenon of migration by cataloguing foreign bodies in “the jungle,” which, by means of the ethical, rethink the aesthetic. I am referring here to the works of Laura Waddington, Mathieu Pernote, Estefania Penafiel Loaiza, Maria Kourkouta, Nikki Giannari, and, finally, Sylvaine George.

Lara Kelemen’s multimedia installation in Warsaw is a bit different from the one showcased in Timișoara. It is therefore a highly adaptable work, but it continues to function as an interface between the individual and artificial experience of isolation and the access to the natural world. The installation was placed in the basement of the Warsaw gallery. The green screen becomes here the perfect metaphor for a synthetic world in which the boundary between skin and landscape is virtually amplified and poetically decoded by the artist through audio-textual inscriptions incorporated in the installation. We are shown both a micro- and a macroverse. On the one hand, the work is precise, made of hard elements: monitors, metallic parts, cut stone, and, on the other hand, the artist underlined the feminine dimension that she tried to incorporate. I could not help but think of the national survey that took place during the time of the exhibition, with its data represented in precise rectangular columns, published on two national news portals right after the exhibition closed. 41 percent of those interviewed (especially women, people living in the city, and people with university degrees) would like for the refugees to be treated humanely, while more than half (52%) of interviewed Poles supported the government’s pushback strategy. The most ruthless are old and young men; right-wing voters constantly try to outdo each other in terms of resentment, indifference, and fear of strangers. However, compassion and the willingness to help overtook the feeling of danger, aversion, or indifference. 70% of surveyed women said that they had positive feelings towards the refugees. The discrepancy between feeling and action – supporting measures to offer them asylum rather than push them back – can be explained by the high level of perceived threat (32%) that they feel towards foreigners. That could explain the much lower figure of 60% when it came to being in favor of asylum when compared to simply feeling empathy for them among the interviewed women.

Sorina Vazelina arrived at the exhibition with a suitcase, just like Marcel Duchamp, the reinventor of art, started on his exile. Sorina Vazelina’s suitcase contains an entire world. She managed to fit in the whole Traian neighborhood of Timișoara, with all its inhabitants and complex multiethnic history. The neighborhood found itself theatrically transposed in Warsaw. I encountered hundreds of faces, noticed architectural similarities, and remembered that it is not only in Warsaw that ancient trees in old parks are being mercilessly chopped down. It also happens in Timișoara. It is not just in Mazovia that “foreigners” have been driven out / deported, but also in the region of Banat, and the traces of disappeared trees still persist in the fabric of Timișoara (like in Warsaw). Furthermore, the figures and buildings in Sorina Vazelina’s suitcase were sculpted from the wood of trees recently evicted from Regina Maria Park in Timișoara. The artist had previously been involved in a campaign to save them. Her work is also an homage to those felled witnesses of history but also an assurance that their testimonies will not be lost forever. The scene in the suitcase is an explosion of color, detail, and vitality, even though the story it tells includes frightening gaps that we should not cease to think about if we want to try to avoid repeating personal tragedies and systemic atrocities, even though we continue to repeat them, commit them, to not understand the past, to think dehumanizing others is alright, because what could foreigners possibly want on our land if not to idle about, steal, go on welfare, and rape, right? Sorina Vazelina helps us persist in opposing this, in stating loud and clear our disagreement with the crises brought about by defective and nazified politicians, and perhaps to get us to reconsider this entire political system which continues to raise to power individuals who do nothing but fart out snuff laws. (At a press conference a little while after I feel something, don’t know what, two Polish ministers, following the tradition of Nazi propaganda, showed fake stills from pornographic films, claiming they had been found on the phones of asylum seekers in Białowieża, in an attempt to justify the state of emergency and stem the population’s growing discontent.)

Sorina’s sculptures were accompanied by a zine with distinct portraits of the Trajans of today. A number of comic strips signed by Vazelina were also passed around at the closing of the exhibition; they documented the deportations and a few waves of refugees from and into Romania.[4]

The activists from the House of Nature and Culture in Białowieża Forest also brought a kind of comic with them. Until fairly recently they were fighting state-sponsored deforestation, and today, forced by circumstance, they are on the front line of the humanitarian aid guerilla in the service of the people traveling the woods seeking asylum in Poland. In fact, before their lecture at Zachęta, we met at a protest around the humanitarian crisis that had been going on for more than a month at the EU-Belarus border. The comic they offered the visitors was conceived as a guide for supporting sustainable practices as a lifestyle, and for getting closer to nature. They also spoke about psychological self-care techniques in case of burnout. Art can play a crucial role in this sense. It seems that improvisational theater is an appropriate tactic, and the group often makes use of it. More and more actors are part of their collective. Those present at the closing of I feel something, don’t know what took part in an improvisational exercise imagining a posthumanist future with no deforestation, purges, hatred, pollution, and violence, full of mutual understanding and solidarity.

Anna Siekierska deals with the hunting towers installed throughout Polish forests, used to increase accuracy during hunting. Poland was blessed with environment ministers who not only gave carte blanche to unlimited deforestation but were also keen hunters themselves. They granted great concessions to animal killers, for example encouraging, through a decree, the massive culling of the boar population through hunting. Examples of questionable hunting behavior returned to the public discourse after videos were posted on social media showing sadistic hunters having a laugh at the slow spasmodic death of animals wounded by their pellets. Siekierska not only documents these structures of death but also advocates for the “necessary destruction” of those objects and killing practices. In one video we see a hunting tower being engulfed in flames.

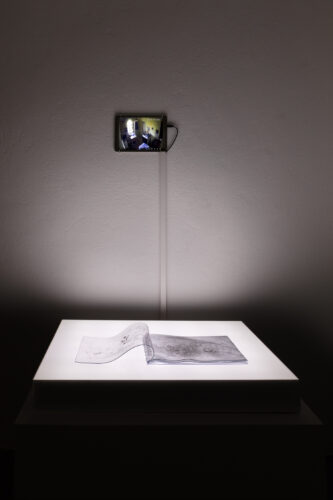

In his new project displayed at ZPR, Section II, negative of a fragment of an uncovered cave, Mikołaj Szpaczyński explores the topics of wandering and escapism. The viewers could see a video work, a clay sculpture, a sketch, and a chisel. These objects tell the story of the discovery of a cave. A few million years before the dawn of humanity, near his home (in contemporary Jaworzno), water carved a cave into the stone. Then, in the following millennia, the cave was completely filled up with clay. The cave’s inside became a capsule in which time and space disappeared in the compact earth mass that filled it. Between 1900 and 1980, a number of quarries were dug in Jaworzno. During excavation, the cave’s clay-sealed entrance was uncovered. For two years the artist has been digging and removing the clay from this cave, slowly reestablishing its existence. Until the present, he has cleared 20 meters of underground passages, removing tens of tons of clay. The cave can end at any moment or could go on for hundreds of meters more. The fossils discovered there date from the Triassic, making it an extremely rare find. Extracting the clay from the stone is like sculpting. In this case, however, the artist is merely an assistant of nature, unveiling the sculpture that it has created. Szpaczyński compares this exceptional escapist experience and his work on the project with meditation, in the company of bugs on the walls, twisting his body oddly in an attempt to make his way deeper into the rock. Once cleared, the cave could become someone’s shelter or hideout. The work was in the gallery’s basement, and the wall on which the video was projected seemed to open up into the abyss.

Together with the cave discovered by Szpaczyński, one finds Andreea Medar’s multimedia installation, a poetic collage made from various elements, starting from childhood memories, family stories, and the memory of a place that has almost disappeared. The central figure is the artist’s grandmother, a peasant from Racoți. Observing the decay of the village and its specific features, the artist reconstructs a model of her house and brings to the exhibition space a collage of nature and artificial parts, a drawing album with thick, transparent plastic sheets, together with the image of the grandmother doing her daily tasks. Romanians, like Poles, despite being stuck in the vortex of migration, are able to return to their roots. Perhaps the families of migrants from places farther away who reach Europe, including Romania and Poland, do not have to become lost in waters or forests.

In the Timișoara exhibition, Janusz Łukowicz took a piece of advice from a magazine literally: in order to be happy, you need to do a good deed, more precisely, to volunteer in Riverside Park in New York and plant flowers. Łukowicz took a plane to New York, cleaned up a few spots in Riverside Park, and planted some flowers. The action was documented in a video work. In Warsaw, the artist showcased a new work inspired by a newspaper article – an homage to Greenpeace. The French Ministry of Transportation JB Djebbari stated that the climate crisis could be solved by developing a “green airplane,” a zero-emission engine, before 2035. Greenpeace activists in response, seeing the proposal as insufficient, painted part of a “standard-emission” plane bright green. Łukowicz reproduces this green spot in the exhibition space. the similarity of the activists’ medium, “borrowed” from art practice, is striking, said Łukowicz. The artist investigated whether the efforts of climate activists and artist activists have a similar potential for success in privileged societies. Let us not forget that planes are still a privilege, but they have an impact on the whole planet.

We have certainly gone beyond the decent level of subliminality of the message I want to convey to you. What you have before you is a text of explicit, engaged art criticism. Still, I don’t feel I’ve “crossed the line.” Following the profiles of the artists who participated in the exhibition (most of them are women – the Guerilla Girls would be proud) have declared or shared similar content to what I have tried to put forth in this text. And even though the police forbade children from drawing houses on the ground in front of the border police headquarters in Warsaw (a group of parents protests daily against the pushbacks) and activists are forced to offer guerilla assistance in the middle of the night to the wanderers in Białowieża, a tabloid has just published a story about how border police officers saved a 17-year-old Congolese girl from freezing. Currently she is in a refugee center, and she will likely stay in Poland. The press officers of the border police can brag about how the institution on behalf of which they speak has done a good deed, even though they have already become memes. Journalists from a civic news portal, on the other hand, have managed to track down at least two of the girls pushed back into the woods, so the children have not frozen to death, they are still alive.

Erich Maria Remarque once stated[5] that artworks are like immigrants. Nobody asks them what they want to tell us, instead using them as they see fit. To be consistent in my disobedience, I hope I have managed to direct your eyes and ears a bit towards the travelling works in I feel something, don’t know what and have made you feel their presence, at least a little bit. What remains is to ask them what they are trying to tell us. And to listen to them.

The double exhibition I feel something, don’t know what took place in Timișoara, during 15.04 – 5.06.2021 and in Warsaw, during 02.07 – 12.09.2021.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

[1] The exhibition was partly displayed in Timișoara as well.

[2] https://posthum.ro/post-h-um-1/donna-haraway-un-manifest-al-cyborgului/.

[3] See also Michael Rothberg’s Traumatic Realism.

[4] They can be read online here.

[5] In his novel Shadows in Paradise, way before art critic W.J.T. Mitchell.

POSTED BY

Teodor Ajder

Teodor Ajder was born in Chișinău. He studied psychology at Babeș-Bolyai, Cluj-Napoca, and got his master's degree in education sciences and his doctorate in media, information and environmental sc...

Comments are closed here.