Fragments from a conversation between Michele Bressan, Ruxandra Demetrescu and Diana Marincu, on the occasion of Michele Bressan’s solo exhibition “There are no bad trips, only fear” at Strata Gallery in Bucharest, 4 March – 8 April 2022.

Ruxandra Demetrescu: We are glad to be here, on the closing day of Michele Bressan’s exhibition, in this gallery which benefits from an outstanding space. We are looking at a very interesting artist who you might already know, and a talented and imaginative curator with whom he collaborated in the past. Maybe a few words about Michelle could be helpful: he is part of the generation born in 1980, graduate of the Art University in Bucharest, the Photo-Video department, with numerous activities as a photographer. I would add that photography and video were always in a fervent dialog in his artistic practice. Another significant aspect are the projects in which he collaborated with other artists, such as Bogdan Gârbovan and Nicu Ilfoveanu. I think this collaborative dimension shaped your personality, Michele, and maybe we can start the discussion from here.

Michele Bressan: Related to collaborations, I would say I actually wished I had more. In 2005 when I applied for the University, I was lucky to see myself in this love triangle, this “bromance” with Nicu and Bogdan. We collaborated without realizing we collaborated. It was something very spontaneous. Each of us was driven by photography. Things got settled and I remember precisely the situation when I realized we were only meeting to talk about photography and do photography, and to work together. Everything was gravitating around photography, almost maniacally, but in a good sense. Even though along the way each of us became established and went their own way, we continued communicating and bonding. This connection between us was very present and the only one of this kind. I collaborated more with curators, like Diana. We worked together on different events, such as for the exhibition “Pasaj” at MNAC, in the Photography Annex, where I used different media for the first time. Diana was the one who imposed different works, like Madonna. With that occasion, I gained more confidence and it was important to have that type of curatorial dialog and to see the works in the space.

R.D.: Today everyone is doing photography. I think in your case it is more about a passion for images. There is a nuance here that maybe deserves elaborating on.

M.B.: It’s an ambiguous nuance. This distinction between an artist and a photographer still exists. I was a “photographer” for many years, and so did Nicu. From one point onwards, people started to name us artists. There is a gray area in this regard, but yes, it is about a passion for image, which can be photography or an adjacent, parallel reality. For me, even the artwork-as-object is thought of in a photographic way. The entire exhibition here is a “frame” which encompasses different types of images, a bigger picture.

My passion for photography did not come from my family, parents or relatives who practiced it. I chose photography because it was the easiest and the most forthright way to express myself without being dependent on other materials. I think it’s the easiest way to become a “collector”.

R.D.: You mentioned a crucial word here. I know you collect objects, all sorts of objects. What we see in the exhibition is proof of this “obsession”. It is about neglected objects which others throw away and which you repurpose and recontextualize.

Returning to the exhibition, a first aspect which I thought is interesting is the fact that there are many works exhibited for the first time, from a significant timespan.

And for this I would ask Diana, how you decided on this “rediscovery” of works which have not been exhibited so far.

Diana Marincu: It was a tremendous pleasure to work with Michele Bressan as one of the artists who truly inspires me.

In this exhibition, I would say right from the start that nothing was accidental. Michele is always very thoughtful about what he exhibits and when. Unfortunately, the exhibition was marked from the very beginning by two brittle events, which cannot be ignored in relation to the exhibition’s theme: the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

When we selected the works together, we thought a lot about the atmosphere they create and how they communicate in space, but also about the “hidden” laboratory of the artist, the works which remain unseen but which represent an important “link”.

The fact that Michele brought up into the discussion the other exhibitions we worked on is important because in those exhibitions he always experimented with different creative media.

The thematic chapters in this exhibition are connected by a red thread concerned with human fragility, the ancestral fear, which the titles also suggests, and this marginal, peripheric universe.

R.D.: The first thing I found striking was the ambiguity, interpreted in many ways—an ambiguity on the level of the objects’ visual expression, like for instance, an entirely atypical work, the drawing on the blackboard with a title which you can perhaps untangle.

M.B.: It is a drawing I saw near a kindergarten and its heaviness was unsettling. It was a drawing of an ambulance, a graveyard, naked bodies and a text “Dueath comes to get ya”. I was surprised that some children from kindergarten would portray such things. I was glad my phone was dead and I couldn’t photograph it. I tried to recreate that drawing on blackboard for eight months, using my memory. I had the boards in my bedroom; I was waking up, deleting, drawing. At some point it became slightly manically. And when I couldn’t do it any more, I told Laszlo “this is it, we take it to the gallery”.

Related to what Diana was saying, nothing is accidental, but at the same time everything is somehow left to chance. Including these blackboards which are not fixed; they will disappear, drawing is ephemeral.

R.D.: Another aspect which I find striking is the angle from which you can see the works: and I mean the play between the close and the distant view. If you look from a distance, you can identify another medium in a work. I thought you were forcing the materiality, cultivating the eye’s deception, maybe on purpose.

For Nonno it is about the “ruin” of a portrait, sprung from a mistake.

M.B.: Yes, in some of the works you can find this ambiguity, of inter-media or inter-moments presence. This ambiguity generates tension, a functional and polyvalent tension. It often supports a state of awareness and curiosity and makes things move: you rotate a wheel, an arc strains, and the mechanisms start or restart. Someone looked at the blackboards for minutes thinking it was a photograph. Someone else thought that the work Vă Rog Frumos/ I Beg You is an intervention made on the gallery walls, when in fact it was a photograph. The mistake which brought Nonno to life is redeeming, the moment which makes the difference between “another portrait” and that “other thing” which is impossible to put into words.

R.D.: I see an ambiguous tension also in some works where we discover a very precarious medium, a factory which no longer exists, an atelier for props pushing out the leftovers, an abandoned discotic. When you look at them, it seems as if they are archeological fragments. As I was discussing with Diana, it seems to me you are playing with different temporalities.

D.M.: Yes, in my discussions with Michele, there was an interesting idea which he referred to as “the past that is about to come”. The play between the medium ambiguity and the temporal ambiguity is captivating. The images we are discussing belong to a suspended past, a time which can be inflected in different versions of the future. And this to me is connected with the idea of ruins or what you just mentioned, the ambiguity of the appearing fragments. Fragments of some antique statues or fragments of props made yesterday. Talking about ruins, I want to bring into the discussion a text by Andreas Huyssen about the nostalgia of the ruin in which he said: “Within the ruin’s body, the past is both present through its remains and inaccessible, transforming the ruin into an element which particularly favors nostalgia.” Nostalgia is defined by Huyssen as “an inseparable blend of spatial and temporal desires”. And I believe it is relevant for the way in which Michele works with a paradox, with space and time, but also with the encounter between past and future. Maybe it would be interesting, in relation to this, if Michele could tell us about the absolutely magical moments in which he found these elements.

M.B.: That temporal ambiguity you were mentioning is directly related to photography—as the quintessence of this ambiguity. The pictures we are taking belong to the past, we don’t photograph what we see. We catch an echo of the things we have already seen. We were talking early about time, if we can count the seconds without looking at the watch. In fact, while you are counting them, they are already gone. If you take upon yourself photography at this operative level, you take upon yourself this passing of time. Besides the fact they are archeological traces, they embody multiple layers.

To be honest, I try not to be nostalgic anymore, I prefer to believe in “accidents”. All are some happenings I “framed” in a medium or another. I think that no matter the work, those which are more present, more spectral, are related to something I want to achieve or materialize. It is something that makes me go on.

I will tell you something which might sound strange or normal at the same time: I don’t like my works, I cannot stand them, which creates an anxiety, a state of tension, a search, an inertia.

My studio is mental. All my works take place in my thoughts and when I materialize them into something concrete or “display-like”, they are in the past. The exhibition, even though it was postponed because of the pandemic, for me it already took place. Exactly like the photographs we were talking about; it is also about the discourse of disappearance.

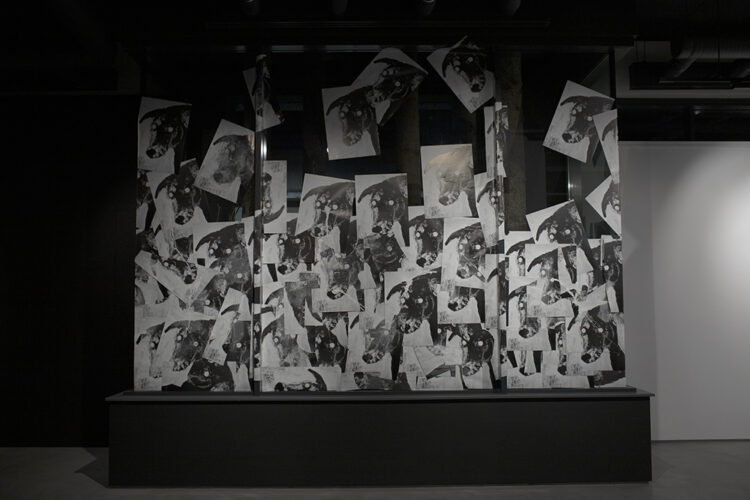

R.D.: There is also a particular object you can pass by without noticing. It looks like an ordinary object, but it speaks about the eye’s capacity to record, to form an image: it is an eye watching us and making us watch differently, which is also in a dialogue with the eyes of the dogs. The first thing that struck me in the exhibition was the intervention of the dogs, and then the title. I was thinking why Câinii lui Tonitza/ Tonitza’s Dogs? And then I realized that the eyes of the dogs are empty, blind, like the eyes of Tonitza’s paintings of children.

Maybe you can tell us how this installation got here. The gallery has some “obstacles” you had to work with, like this glazed space.

M.B.: The black dog is a recurrent theme. It was quite natural; it was a “virgin” space which we didn’t know how to work with, and then I realized that this dog has a connection with the exhibition title and that fear encompasses a larger meaning. I wanted to experiment and get out of my comfort zone, without the fear of being validated only through photography. It was a cut from a drawing I did some time ago which I never planned to use but finally found its place here. And I think this exact hypnotism became present.

We tried to create a relation between all the exhibited works, and the exhibition to become an immersive single-work experience.

It was difficult to manage the space; during our preparatory meetings I discussed this together with Diana, so that it does not become too daring but also not too fragile. In the end, we gave up on some artworks instead of adding. An idea we can take from this is that absence is as relevant as presence. This creates that frequency which transmits “particular postures” for some receptors.

I think “art”—a very slippery term—is like a song you like and you listen to on the radio, and while disturbed by other radio posts, you try to fix it and adjust the volume. The volume is put louder than necessary, consciously or unconsciously, so that others can hear it and perceive from the same frequency. Many times, a solo exhibition is considered a climax, the culmination of a work. But for me, the exhibition is like a burial stone by which I leave something behind and through which I exorcize something.

R.D.: By the way, since you spoke about sounds, the exhibition also consists of a sound universe, made by you, a collage of sounds. The dialogue between image, sound, and word is significant. The last work, maybe the most ambiguous, Fine, also has an amusing story, like the one with the handyman who helped you make it and who was saying “this is so fine”.

The sound in the background has a striking density and materiality. And I was wondering to what extent sounds and words are important to you. Those close to you know about your passion for literature and poetry and this matters as a personal cultural background.

M.B.: These passions were cultivated through others as well, like for the book T made with George Nechita, who is present here. I realized he “reached” the frequency and that is how we met, in a zone of sound distortion. From that “distortion” a book came out.

Similar to fear and exorcizing, I will tell you about the “sound” process. I have a sampler at home which I barely know how to use. I push some buttons, and luckily, the generated sounds correspond with my feelings. Also related to eliminating fear, during the set-up, the discussion about sound and music came up, and the people from the gallery considered that what I showed them sounded good. I believed in them, just how they believed in me, and so we included the short sound extras in the exhibition, which complements it and congeals the space.

The word Fine in the black room at the end is also related to the idea of an end which captures my experience and communicates well with the black panels placed in a crescendo in the gallery glass.

It is interesting to offer background details for the works, like the work I Beg You, but at the same time I think each work can be assimilated without a “prescription”. Such as for this work which has a universal and poetic message, and also a story. In an area in Bucharest which I visited quite often, there was a fence scribbled with all sorts of interventions. The words “I Beg You” belong to the house owner who was tired of all this. This seems like an intimate request to me.

For me it is a very personal and necessary exhibition.

D.M.: I have to admit I’m most fond of the work Fine. I see it as a mix between a dynamic and static image; at first sight, it gives you the impression of that “fine” from the end of a movie. But in fact, it is an image which monumentalizes space. Time stands still, and the viewer petrifies together with it. You are part of that infinite final moment, a total suspension.

I think the relation with cinematography is important. Michele, in relation to other works of yours connected to cinema, maybe it would be interesting to draw a parallel with your series Waiting for the Drama.

M.B.: I did happen to realize how my works were created and surprised myself with that. One of my favorite movies is 8 ½ by Fellini; in one sequence, a magician writes with chalk on a blackboard the words “ASA NISI MASA”, a sentence related to the protagonist’s childhood. Fine is related to something very grounded. When I was a child, the moment I knew I had to go to bed was when I saw the “fine” word on the TV screen. In the case of cinemas, I noticed these spaces are presented only through the perspective of their activities. What happens in the transitory moments? Between two screenings? There is an interesting tension there and that is why I photographed those intervals. After many necessary approvals, I photographed right during the twenty minutes of “emptiness”. I was interested in the chairs, not the screen. Afterwards, without any connection to my project, these cinemas disappeared. This photography series was like a premonition. Related to the meaning of ruins and disappearance, or the Fine, can we ask ourselves what remains. Photography remains.

R.D.: The last thing I wanted to touch on was the manner in which you photograph nature. I always thought that in your work the city always absorbs nature.

M.B.: I grew up far from the idyllic, alluring nature, or the ideal and idealized landscapes. I didn’t experience life in the countryside. I was born in the city, lived in an apartment, but I longed for that relationship with an idyllic surrounding which I always associated with my friends’ holidays. I always faced the apartment bloc in the front, seeing myself in relationship with the urban landscape and the close vicinity of cities. I think I slowly embodied these details.

R.D.: I think we can identify the power of the details throughout the exhibition.

M.B.: As further you go in paying attention to these details, more answers and questions are revealed. As I was saying earlier, I believe more in absence than presence, just as much as I believe more in questions rather than answers. It’s a different endeavor and effervescence. The exhibition is full of details that “grab your hand”, they lead you but do not force.

D.M.: In relation to these observations of nature which do not appear here neither aesthetically nor poetically, but fragmentary and decomposed, I would add something else. The human figure appears in a similar way—it’s a scattered humanity. The work we were talking about earlier, that fleshless arm gives you the impression of canceling the integrity of the human figure. And I find it interesting how this common body is created by the suggestions of human figures within the exhibition. They become a collectivity which finds itself in a radiograph room, the exhibition. It doesn’t show anything, it shows everything, it shows you even what you don’t want to see.

M.B.: Not long ago I had an epiphany. A moment in which I suddenly realized I rarely take photos of people. At the same time, I became more conscious of the way in which I suggest the human figure: almost never in a clear manner, explicitly, or immediately recognizable; most of the time I do it in a fragmentary or spectral way. Each photograph functions as a radiograph, and some of them get to see more than others, and manage to go deeper. The photography of the hand and the arm / the concrete object of the work Go West is only apparently contradictory. They both coexist in the sphere of fragility, absence, and uncertainty. An area in which we often know what we are looking at without knowing what we see and vice versa. Not to forgive anything means not to forget anything, and photography transcends this. I think a good part of the discussions and theories surrounding photography can be encapsulated in an anecdote. I was somewhere near Cluj when I documented the religious pilgrimages in Romania. I couldn’t take many photographs. I was ashamed to “bite” those people with my camera. At some point, a woman came to me and asked to take a picture of her; I gladly accepted and said the usual: “please leave me your address, I will send you the photos, it’s a camera on film, I cannot show them to you now.”

Her answer was unexpected: “I don’t want the photographs. I don’t need them. I only want to know someone photographed me now, here.”

POSTED BY

Diana Marincu

Diana Marincu is a curator and art critic, member of AICA and IKT, Artistic Director of Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara. Her recent exhibitions include: At the edge of the world (co-curator: C...

Comments are closed here.