Wednesdays to Saturdays, around 12 pm, I make my way to Suprainfinit Gallery, where I am currently working as a curatorial assistant. It’s a 15-minute walk from home under the greyish tones of Bucharest’s winter sky, traversing a lively neighbourhood I know oh-so-well, emotionally-charged squares and street corners. I pass by the concrete structures of the so-called Mantuleasa Park, by Mircea Eliade’s statue – embellished as always with a considerable layer of pigeon faeces –, and arrive at Suprainfinit. By now, my clumsy hands have learnt the sequence of movements required to successfully unlock the gallery door. Yet ever since the opening of art collective Apparatus 22’s solo exhibition Of Pleasure: The Learnings and Strange Fortunes of Atletica Ideal, which took place this mid-November, the morning ritual ends with a set of pensive gestures.

The movements are triggered by the shimmering VHS-tape curtain, part of the installation The Owls Are Not What They Seem, that now hangs before the entrance, as well as cuts through/brings together the infinite entry-exit points of the exhibition in an irregular sense of intimacy. The ends of the VHS strips get blown outside by gusts of wind, and I am made to wonder whether to bring them back in or not, whether to tame SUPRAINFINIT, Apparatus 22’s queer utopian universe, or to let it contaminate the dichotomy between private and public space. No matter the human effort, the flying tapes remain at least partially uncontainable.

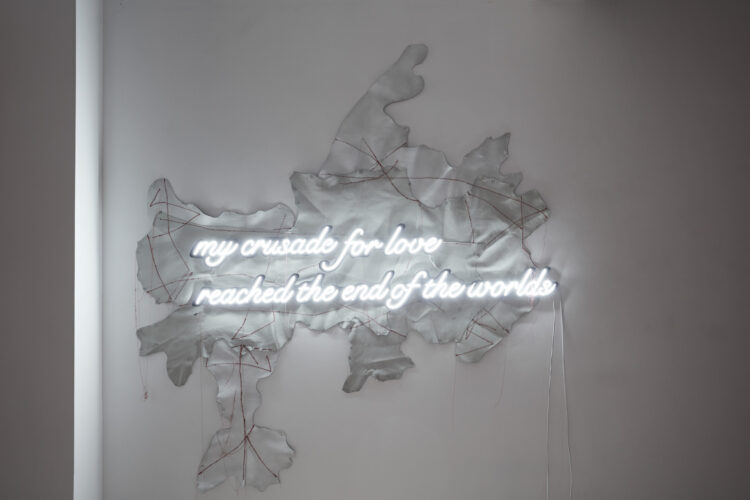

The works of the collective have a disorienting effect even within the gallery itself. They disrupt my usual path through the main exhibition space and towards the back office, as my attention is diverted by the show’s kinky aesthetics and the multiple textures mobilised in its construction, from the tapes to the neon, from the deconstructed leather flags to the goth bird figures. I turn on the video works. The temporary inhabitant of the space, Atletica Ideal, an A.I. machine in search of love and pleasure, imagined by the collective’s current members, once again forces me to think – in the unusual context of daytime office labour – about the limits imposed on sexuality by conceptions of The Natural [1].

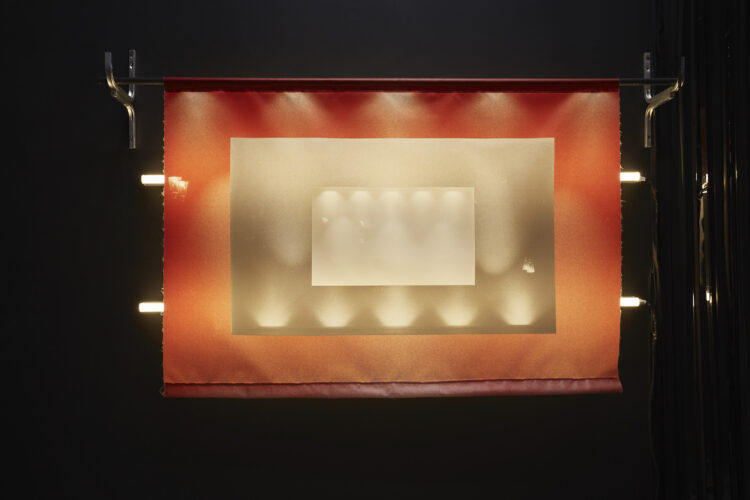

In a 2018 article published by Tate Papers, artist Amba Sayal-Bennett explores the ways in which embodied methods may inform art history, theory, and criticism[2]. There, Sayal-Bennett critiques the epistemology that often guides them as one that separates representation from lived reality and from art practices themselves. In a similar vein, this series of notes is devised as a situated attempt at writing auto-theoretically and auto-ethnographically about the Apparatus 22 show at Suprainfinit Gallery, from my (differential) perspective as an exhibition custodian. During the first month of the Apparatus 22 show, the gallery became a space of personal reflection and of speculation about the ways in which queer art practices may inspire certain specific political reimaginings. The article ends with a poem I wrote about the installation skeleton of lightbox (2022), one of the many aspects of the exhibition that unconsciously entered my thoughts, my routines, and my dreams.

The solo exhibition Of Pleasure: The Learnings and Strange Fortunes of Atletica Ideal at Suprainfinit gallery is still open to visitors until February 4th, 2023. It showcases 20 works by the collective, most of which were produced in situ, installations that draw on Apparatus 22’s practices that have crystallized over the past 7 years: “long-lasting experiments (…) to transform artistic research about the future ~ the unknown ~utopia into complex narratives, working leather into magical~visceral~kink sculptural forms, the hyperbolic intensity and queer sensibility imprinted on perspectives that may be included in the sphere of science-fiction”.

01 The materials of utopia

The week before the opening, the gallery turns into a lively art studio, as the collective’s members join forces with the art technicians to bring the show to life. I am here both as a witness and a helper, and what particularly sticks with me is the three artists’ well-coordinated efforts to bring the many materials and media of the exhibition together, from sewing up the leather pieces to assembling the wooden and metal totem installations and drafting up the exhibition texts, as authorship dissolves through collective practices of doing. And as someone who struggles with motor planning and spends most of their time writing, I am glad to discover the work environment of the collective as a safe space and as one where making is seen as a mode of liberating oneself from the constraints of the textual. While Apparatus 22’s SUPRAINFINIT may be easily described as what Jose Esteban Munoz[3] saw as a concrete utopia – one that is “relational to historically situated struggles” –, witnessing its making triggers me to consider ‘utopia’ as necessarily entangling between doing and thinking. I wonder about the materials used in the process of radically transcending and transforming the real. What are the textures, the smells, the fabrics of a queer revolution?

02 To all the inner parties

I wait until the time of the opening to have a proper look at the exhibition. Walking in, the gallery has transformed once again from a hectic working space into an enticing, red-and-white neon-lit darkroom, enveloped in the atmosphere of a rave. Although missing the high-bpm rhythmic flows of a club night, it is a similarly trance-like state of reflection that Of Pleasure induces in me at first glance. The exhibition immediately speaks to me – as queer raves have in the past – about gender dissidence and body acceptance, of a counter public where what is socially rejected as abnormal and deviant may be genuinely explored and performed. The asymmetrically arranged installations have a diffracting effect on my gaze, the central point of attention no longer being the gallery walls, but the infinite visual mazes of light and darkness that emerge with the help of the VHS-tape (anti)curtain, hiding or making visible certain groups of visitors engaged in conversations. Common objects such as bed frames, birdhouses, leather jackets, gloves, flags, and bike seats, displaced from their usual function, become queering devices that disturb the social order of things rather than make it familiar[4]. I see people that I know or that I know of at the opening, yet their presence is made uncanny to me, as if the setting of the show has displaced them from a social semantic chain, previously wired in my brain.

What is equally enticing on the opening night of the exhibition is how its form and narrative content come together. The more I think about it, the more I see why Atletica Ideal’s quest for love takes place in this particular universe. The envelopment of kink engenders an affective context that makes it possible to reflect on something which Apparatus 22 member Dragoș Olea describes on multiple occasions as mindfuck – AIs as sexual beings, having sex with artworks no less. With regards to certain BDSM subcultures, Mel Y. Chen reads the use of dog chains and other “accoutrements of animals” as participating in the construction of complex power relations, as well as in fostering “a sensualized sense of animacy”[5]. When kink and AIs queer each other in SUPRAINFINIT, I am begged to think of sexuality as beyond the realm of biological animacy, in a cyberspace-made-material where sexuality and pleasure are a matter of fantasy, of future possibilities and their expansion rather than of past/present encounters.

03 Soundings

Days go by, and as I get more accustomed to the visual workings of the exhibition, its sounds increasingly populate my thoughts. As I am working from the office desk, I can hear the two streams of audio emerging from the videoworks Sex Tape VIII and Sex Tape III perfectly. Each day a slightly different overlap between the two gets concocted, depending on how loud I turn on the volume or how quickly I move between the two screens as I click ‘play’. Sometimes I mute the videos if there are no visitors, but most often I choose not to. On most occasions, I enjoy discovering the new dissonances and I progressively find that the repetitiveness does not turn them into background noise. I start to memorise the lyrics, without meaning to. “I wanna crack your universe a little wider”, from Sex Tape VIII, is what – unwittingly on my behalf – ends up playing on and on in my head as I go about my day, whether I find myself in the sonic presence of the videos or not. As my encounter with Sex Tape VIII becomes a matter of routine, the unqualified intensity of the lyric penetrates my mind until it becomes fixed[6], developing conscious meaning. “I wanna crack your universe a little wider” turns into a motto of my personal explorations of gender – I crack former selves to find new embryos of Maria.

Although this was not the first time when the daily encounter with an exhibition engendered increasingly embodied and visceral emotions, it is with Of Pleasure and the cracked universe in Sex Tape VIII that I am starting to think of art and its audiences in terms of time. Gallery encounters between visitors and the showcased art are of a fleeting kind; they are durationally short experiences that may facilitate the affective making of art objects into something exceptionally distinct from the materials of everyday life. As a gallery or museum worker, inhabiting the world of exhibitions entangles the slow temporalities of the quotidian with the extraordinary qualities of art objects, as one becomes progressively accustomed – or further estranged – with their unfamiliar vocabulary. Artworks accumulate meanings that slowly derive from affect, from repeated and varying intensities; they get pluralized and personal, drifting between the conscious and the unconscious.

04 Articulating the monstrous I

Atletica Ideal becomes present in my daily thinking not only due to the sonic effect of the exhibition. They intrigue me as a cyborgian figuration for queer and feminist possibilities. I am reading Atletica Ideal together with my past research into monstrosity, and particularly with the portrayal of AI robot Ava in Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014). In the film, Ava is programmed by her male creator, CEO and former genius-child Nathan, to be a docile female heterosexual subject, tailored to the tastes and desires of his new recruit Caleb. Although Ava manages to escape Nathan’s research facility and therefore, symbolically, a patriarchal logic of confinement, her departure depends on an exploitative and hierarchical relation with Nathan’s racialized robot, Kyoko, heavily sexualized and portrayed as voiceless. While Atletica Ideal’s embodiment resembles that of a woman in Sex Tape VIII, their representation is slowly twisted towards fluidity. Rather than reproducing existing hierarchies within the very concept of ‘humanity’[7], Atletica Ideal leads me towards new and unknown terrains of embodiment and emotion, making strange what is oppressive and bound by the normative. When it comes to matters of love and desire, the display of emotions by Ex Machina’s Ava turns out to be a ploy for her escape, replicating the trope of AIs as mathematically rational – and paradoxically ‘savage’– beings. By contrast, Atletica’s quest to become-human by learning the language of love does not lead them towards a human Other to have sex with and therefore to contaminate them with ‘humanity’, but opens up the undiscovered domain of AI-to-art intercourse.

My theoretical interest in monsters, and particularly of the cyborgian kind, stems from the emotional release that their hybridity conveys to me. In my thinking, to situate oneself in-between the human and the machine engenders the possibility to eschew certain social scripts and bionorms, to open up forms of expression that defy conventional forms of emotional existence. Of Pleasure’s atmosphere does not only nurture queer and nonhuman narratives of desire – it equally envelops the unfolding of a story that celebrates neurodiverse experiences. In the episode About the curious digressions of Atletica Ideal. A report, part of the collective’s radio-inspired audio series THE CONTINUUM BROADCAST and where the character was initially presented, Atletica describes their journey in a way that reminds me of the neurodivergent struggle to regulate one’s feelings in socially-accepted forms: “I did everything to immerse in those definitions and depictions of love and pleasure. I hoped something might one day grow inside me: raw, scarifier, oily and nourishing, confusing and irrepressible.” Sex Tape VIII, Atletica’s encounter with The Scream, is partially a response to Edvard Munch’s recently discovered inscription on the canvas that reads “could only have been painted by a madman”. Rather than taming the body deformed by madness, as a faithful subject to the quest for modern progress would do, Atletica proposes to be “the private icon” of the bewilderment generated by the oppressive structures of sanitation.

07 Poem to an art installation

in my dream I was

skeleton of lightbox

I was

floating above

The family nucleus

a particle

of fine metal

shimmering

above the white

warehouse

ambiental neurons

of

acceptance

Apparatus 22 is a transdisciplinary art collective, initiated in January 2011 in Bucharest, RO by the current members – Erika Olea, Maria Farcaș, Dragoș Olea – together with Ioana Nemeș (1979-2011). Beginning with 2015 they are working between Bucharest, Brussels and SUPRAINFINIT utopian universe.

They see themselves as a collective of daydreamers, citizens of many realms, researchers, poetic activists and (failed) futurologists interested in exploring the intricate relationships between economy, politics, gender studies, social movements, religion, and fashion system in order to understand contemporary society. An important part of their work is dedicated to shaping queer futurities.

The work of Apparatus 22 was presented at La Biennale di Venezia 2013, Kunsthalle Wien (AT), MUMOK, Vienna (AT), BOZAR, Brussels (BE), Museion, Bolzano (IT), Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles (BE), Kunsthal Gent (BE), Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz (AT), Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart (DE), Contemporary Art Museum (MNAC), Bucharest (RO), La Triennale di Milano (IT), TRAFO Gallery, Budapest (HU), Futura, Prague (CZ), Ujazdowski Castle CCA, Warsaw (PL), Onomatopee Eindhoven (NL), TIME MACHINE BIENNIAL OF CONTEMPORARY ART, D-0 ARK UNDERGROUND, Konji (BIH), Osage Foundation (Hong Kong), Closer Art Centre, Kiev (UA), Brukenthal Museum Contemporary Art Gallery, Sibiu (RO), CIAP, Hasselt (BE), Barriera, Turin (IT), Survival Kit festival, LCCA Riga (LV), Autostrada Bienniale Prizren (XK), MAK, Vienna (AT), Steirischer Herbst, Graz (AT), Drodesera Festival, Dro (IT), TRIUMF AMIRIA. Museum of Queer Culture (Ro) etc.

[1] Amba Sayal-Bennett, Diffractive Analysis: Embodied Encounters in Contemporary Artistic Video Practice, Tate Papers, 2018.

[2] Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire, Duke University Press, 2020, p. 6.

[3] José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, New York University Press, 2009, p. 3.

[4] Sarah Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Other, Duke University Press, 2006, p. 560.

[5] Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Duke University Press, 2012, p. 105.

[6] Brian Massumi, The Autonomy of Affect, Cultural Critique, University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

[7] Neda Atanasoski and Kalindi Vora, Surrogate Humanity: Race, Robots, and the Politics of Technological Futures, Duke University Press, 2019.

POSTED BY

Maria Persu

Maria Persu (born 2000) is an independent cultural researcher and a member of the editorial and artistic collective specula. She is currently working as a curatorial assistant at Suprainfinit Gallery ...

Comments are closed here.