The Artist As…

If someone is interested in critical artistic strategies dealing with the past, the questioning of fixed and stable truths and the relationship between personal and collective memory, it is impossible to avoid the works by the artistic duo Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán. The artists have been working together since 2011 and since then, they built up a coherent praxis without self-repetition, using various techniques, media and displays. In their works, they attempt to make visible the invisible patterns behind certain historical, social or geopolitical decisions and highlight specific contradictions, mindsets and narratives that shape our world but are rarely questioned. As Magda Radu summarizes it, they “frequently shine the spotlight on the unevenly matched confrontation between the individual – viewed as an autonomous subject within the society – and institutional authority, such as the state, multi-national companies, and art institutions.”[i] I have selected some, to me, especially fascinating but at the same time typical works by Benera and Estefán created in the past 5-7 years for further analysis.[ii] All of them are characterized by a constant balance between a personal starting point and a more general understanding on issues of identity, the re-interpretation of history and the role of the citizen in today’s world.

Each of Benera and Estefán’s projects are dedicated to a certain problematical or debated phenomenon, which the artists try to question and decipher taking up symbolically and often also literally the position of the ethnographer, the historian or the archeologist. It was Hal Foster who stated in his famous essay The Artist as Ethnographer[iii] in 1996 that artists appropriate the role of the ethnographer in their practices in order to understand the Other. This strategy still maintains the binary thinking between the self and the other and also, according to Foster, could result in a narcissistic over-identification. This influential phrase has been incorporated in the discourse on contemporary artistic strategies: from the original notion of the artist as ethnographer many variations spread out, artist as historian, archivist, archeologist or even museologist. What is common in all of these attitudes is that they require a certain kind of research and the critical examination of documents, facts and objects.

The above-mentioned methods are all visible in the practice of Benera and Estefán. Although not all of their projects are based on a long-term research, as Raluca Voinea states it, “they research documents, treaties, official statements, media reflections, years and facts, statistics, agreements and renegotiations, and then propose witty works which provide synthetic – almost abstract in their precision – answers to political conundrums.”[iv] They are open to new disciplines previously unstudied by them and the usage of models, graphs, diagrams – as well-known tools for understanding the world around us – also underlines the interest and attitude of striving to map out a certain situation and its components.

However, referring again to Foster, in the practice of Benera and Estefán the examined “Others” are often the artists themselves. Their self-reflexive approach helps them to understand the shaping and construction of identity. They investigate the role of history and symbols of collective memory in that context and how certain notions can be rethought or revisited from the present point of view. In other words, they rethink, rewrite, appropriate and give new meaning to certain phenomena. In some works more directly, in some works more subtle, but often the process itself and the procedure of understanding, gaining and sharing knowledge become dominant features. Their starting point in many cases derives from a personal memory, a family story or a current situation which caught their attention and through which they address the historical, social and economic context and its framework with an analytical eye. Balancing between the micro and macro perspective, their critical approach is always perceivable, however the several layers of their works might be interpreted by the viewer in different ways.

History/Memory/Identity

It is not a surprise that the artists also reflect more closely on the notion of collaboration: in some cases, the process of working together and the exchange of thoughts are accentuated and the work itself emerges from a literally “common act”. It is precisely the presentations of different viewpoints on a specific event and the collision of these narratives which become visible in one of their most acknowledged projects, entitled Pacta sunt servanda (Agreements must be Kept, 2011- ongoing). This work presents in an intimate yet powerful way how the artists deal with their different (Hungarian and Romanian) origins and backgrounds and what does it mean for them to question the official narratives related to history. In the performance they read aloud and simultaneously from Hungarian and Romanian school history textbooks specific parts on certain historical events that were contradictorily interpreted by the two nations (e.g. the 1848 Revolution, the Treaty of Trianon, 1920). The setting is simple: the artists are sitting facing each other and reading aloud (to each other, to themselves) the selected paragraphs. Neither the artists, nor the audience, can understand fully the narration and the details, as the voices and the two languages are mixed, despite the subtitles. The chaos from the speeches creates some kind of “united” and new perspective: a “third meaning”. The critical analysis of history textbooks (official narratives) could remind us of the Hungarian artist, Zsolt Keserue’s project, titled National Textbook in which he and his team search the stereotypes and statements on Hungary and its citizens in foreign history books.

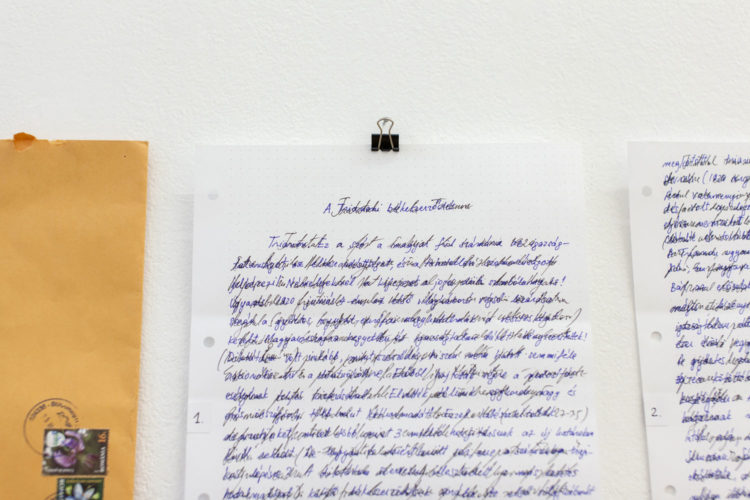

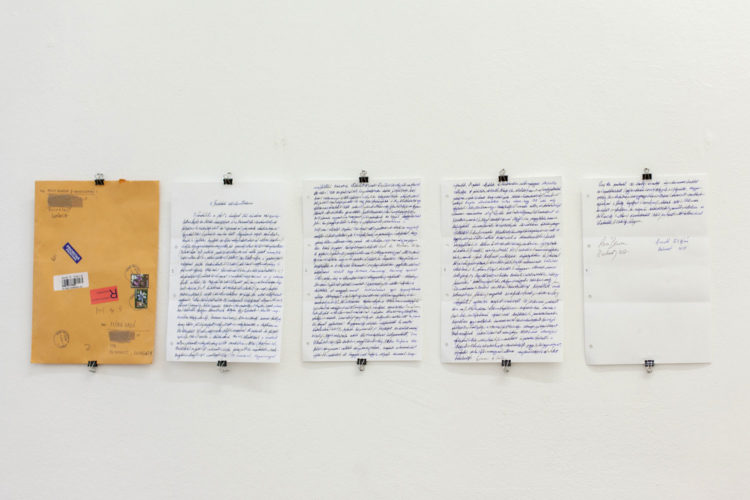

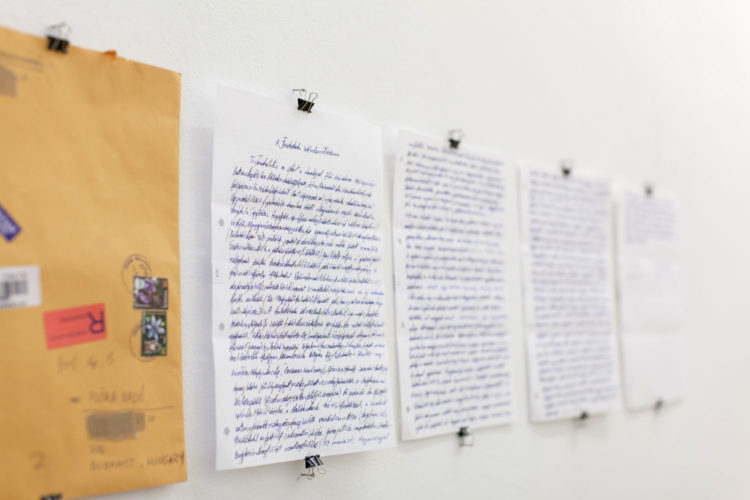

The simultaneous reading in Pacta sunt servanda eliminates both the differences and the similarities, emphasizing that the effort of understanding the other, or the other’s perspective is a missing element in our society. However, certain viewers – like myself – are also bound with understanding only one language from the two, which also results in a one-sidedness, which aspect the performance criticizes. Benera and Estefán’s performance conveys the message that history can be understood differently, “one certain truth” does not exist. History and identity could not be seen as clear, linear stories – they are often confused, interrelated and mixed – the project Pacta sunt servanda sheds light on this postulation. An interesting continuation of this project was the artists’ contribution to the second OFF-Biennale in Budapest this year. They took part in the exhibition For me Trianon curated by Teleport Gallery. Here, the artists were asked to send personal reflections, objects, photos about this specific event, and the duo transformed their performance into writing: they wrote on each other the texts form the history book.

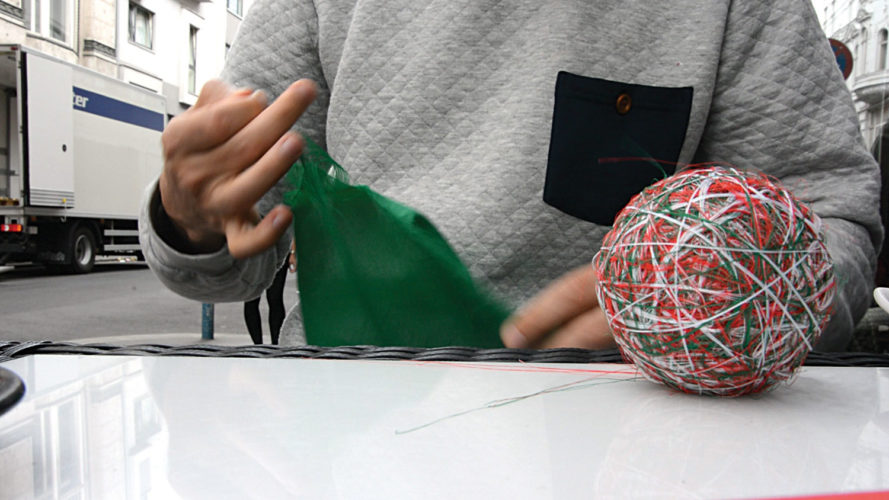

The project Jus soli (2013) challenges further the question where do we come from, what are the components that form our identity and what are the factors that officially label our ethnicities. In this work Benera and Estefán appropriate and give a new meaning to a national symbol, and through this process rethink its current significance in today’s nationalistic discourses. The project foreshadows the artists’ precise, minimalistic and enduring working process which would be seen in their future projects too. The title is telling: according to the artists this Latin phrase refers “to the main criteria for determination of national status of individuals”, jus soli (the right of soil) meaning that “the nationality of an individual is determined by the fact of his birth in the territory of a state”. In this work the artists question and deconstruct the role of such symbols as the national flag of a country and again, they also put into play their different viewpoints due to their background and imposed ethnic identities. They are literally doing this by unthreading those national flags which are related to their place of birth (Romania) and also to their ethnic heritage (Hungarian, Italian, Ukrainian and Spanish) and transform them into colorful balls. At first it looks like an act of damage, but by this procedure the artists got the strict divisions of the colors on the flags disappeared and created new objects where the colors are tangled together. This gesture could also be seen as ironic, playing with our identities, pointing out the flexible aspect of it. We can also associate to Société Réaliste, another (ex-)artist duo, who in their project UN Camouflage (2011-13) converted the colors from the flags of United Nations member countries to military camouflage patterns, thus changing our whole perception of the flags.

Through these newly formed objects Benera and Estefán pointed out the necessity of thinking without prejudices, avoiding the rigid frameworks of nation, origin and country of birth. A video documents the process of this contemplative and everlasting activity wherever it takes place: in a park, on the tram, or at home etc. Jus soli could be seen as a special kind of performance in which the emphasis is laid precisely on the time-consuming aspect of the process which in the end, however, reaches its goal. I consider this prolonged and tiresome feature of transforming the flags a crucial part of the project. The duration of the procedure and the fact that the artists execute it themselves have a special significance: although we develop different strategies to deal with our past and to understand our identity, it could only be done by ourselves and it could not take place in a hurry without (self)reflection. And sometimes it seems like an endless Sisyphean process too. [v]

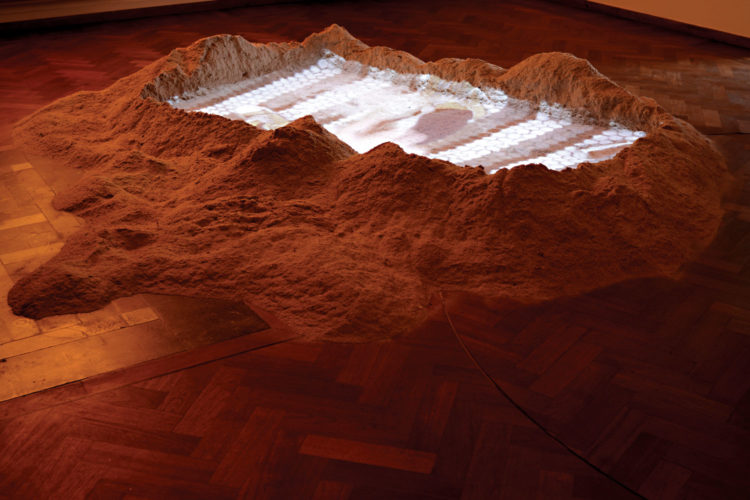

This slow process resulting in a new meaning can be recognized in a later project, called Untitled (2016). It was first shown at the Universal Hospitality exhibition, first in Vienna then in Prague. In this project the personal story is again very strong, as the starting point was the series of events which occurred to one of the artists’ grandparents. As the artists summarize it: “Towards the end of WWII the artist’s grandparents – refugees fleeing the red Army – decided to migrate west, beyond the new borders of Romania established by the Second Vienna Award. Before leaving, as a symbolic gesture, they decided that each would take with them an item of furniture from the living room. In this way they would symbolically be preserving the unity of the family, in the hope that the moment of reunion (of both family and country) would not be far off. Those who had decided to travel the furthest each took a chair, while the two who were to remain in Transylvania got the table and the cabinet.” This story is touching in itself and one would have thought, that it would be a reasonable gesture to reunite these chairs, once finding them. However, the artists did something very different, what I consider as a radical act, and as a consequence the furniture has gained a new form. Through a long process, which they documented, they sawed the chairs made of wood into sawdust and baked bread from it[vi], referring to the lack of alimentation in the times of war.

What would have been a sentimental gesture of reuniting the furniture for Benera and Estefán wouldn’t make any more sense, since some of the family members who wished that, are not with us anymore and it is not possible to go back to that time. We can refer here to the notion of restorative and reflective nostalgia by theorist Svetlana Boym, who in her book The Future of Nostalgia[vii] points out two relations towards the past. According to her, restorative nostalgia means the total reconstruction of monuments of the past and it “puts emphasis on nostos and proposes to rebuild the lost home and patches up memory gaps.”[viii] Reflective nostalgia on the other hand, centers also on loss and longing, but emphasizes the imperfect process of remembrance. “The focus here is not on recovery of what is perceived as an absolute truth but on the meditation on history and passage of time.”[ix] In reflective nostalgia, longing and critical thinking are not separated or opposed to one another, rather this imperfection of memory and the impossibility and uselessness to reconstruct the past as it was, are in the center. For Benera and Estefán the lost and reunited furniture could symbolize home, but they do not wish to “rebuild a mythical place” instead they focus on the collision of historical and individual time.

In a way, the sawing of the chairs could be seen as a destructive act, but also as a special transformation, where a different kind of materiality is being created from the remains, from the saw dust. The method is similar to the one we saw in Jus soli – a long, slow working process which requires patience and concentration, resulting in a new kind of essence. This new quality which is again transformed through the baking and becomes a – black and not edible – bread, could also open up a more optimistic narrative, as bread is often considered the symbol of life and survival. On the other hand, it also raises attention to some “good practices” and methods which we have to learn in order to use them maybe in a not-so-bright future.

Nature/Land/Geopolitics

In their recent projects Benera and Estefán started to investigate wider geopolitical issues, e.g. how in the age of Anthropocene our traces in nature can be witnessed and how nature is used to cover certain political decisions. In their black and white video, titled No Shelter from the Storm (2015) they address the notion of wilderness and the deforestation from a political/historical point of view. The artists are wandering in a forest which once, in its entireness also served as a hiding place for the partisans in the Second World War and also a living place for nomadic people. Today, as the title suggests, there is no shelter from the storm, the forest disappeared, yet the artists try to find their pathway in it, while whistling a famous song 1960’s anti-war song: Where have all the flowers gone. Symbolically, they are walking again the routes of their ancestors, while highlighting how the conditions have been changed since then and pointing out the movement from the battlefield to the virtual (cyber, bio) wars in our times. The video is a poetic response to the massive deforestations in the world but merging it with not only an ecological, but with a political context, referring to their constant yet often invisible correlation.

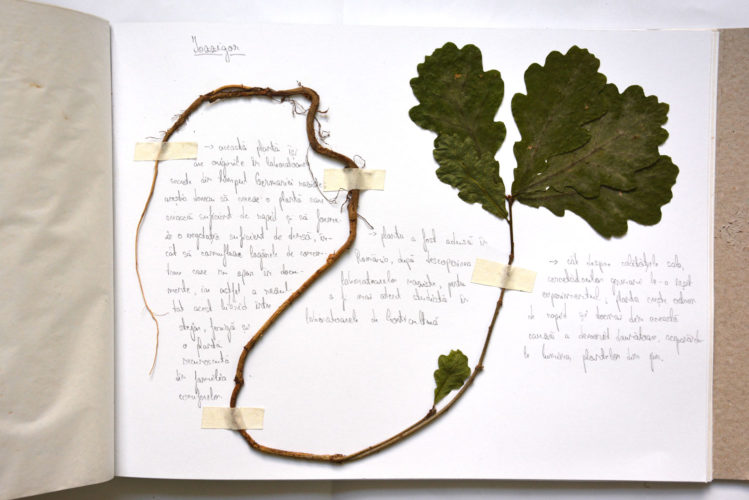

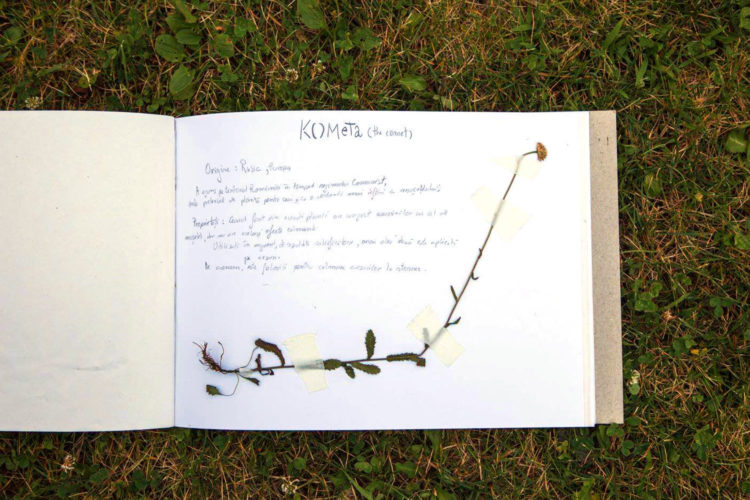

In their new project, currently shown at the Natural Histories exhibition at Mumok in Vienna (curated by Rainer Fuchs) Benera and Estefán present a long-term research project. Debrisphere. Landscape as an extension of the military imagination – displayed as a mixed-media installation – unites several attitudes and directions in which the artists have been interested in the past few years. The core of the project is a study on five exemplary places, which are specific natural sites used for military purposes and are often not visible or known for the average people. We can see architectural scale models of these places – like the Teufelsberg in Berlin which is made of ruins from the former military college that the Nazis founded, or the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, where China created several artificial islands and built military facilities on them – presented in a museological display accompanied by botanical drawings representing the local environment and some strange names (instead of the name of the plants, trees, corals), which turns out to be the name of the militarized island or the operation used there. As curator Raluca Voinea puts it: “The artists talk about landscape as camouflage, nature built on top of a nature of a different kind, erased to create another narrative, history re-written through the manipulation of geology, scenery reconfigured according to the needs of strategic military thinking.” The installation presents itself as a study room of a geographer, with models, scientific drawings and strange collages, yet the topic it addresses, is rarely studied in these academic circles. The five case studies – among there are more and less well-known places – appear as certain non-places (according to Marc Augé) that do not exist in common knowledge, whose existence is camouflaged on purpose. The artists emphasize these invisible mechanisms: although these islands occupy large territories, their function remained unnoticed. The research carried out by the artist duo is broad but precise, yet the fictive aspect of the work is hidden just like these islands are hidden from our sight. Renaming the plants and flowers which used to grow in these places before the military interventions is a forceful gesture which underlines its critical attitude.

The artists continue to go further on this field of interest: their most recent project Herbarbarium takes as its starting point “the new European legislation against foreign non-native species invading local flora, thus altering «national habitats».”[x] In the framework of a workshop, students were invited to collect in their surroundings the plant, flower which they thought is “alien” in that environment and create fictional stories around them. This also fits into a tendency which is dealt by Hungarian artists Bence György Pálinkás and Kitti Gosztola, who reflect on the so-called “invasive species” in Hungary, like the locust tree, which is now found everywhere in the country and is even a symbol in the national discourse, however they were planted on purpose.

Anca Benera and Arnold Estefán continue their critical, analytic practice with the intention to change our approach and attitude to certain notions. Maybe the transformative power of art is still utopian, but through the questioning of official discourses and challenging rigid attitudes there is a chance that our awareness might change.

[i] Magda Radu: The Equitable Principle, in.: Anca Benera + Arnold Estefán. Works 2012-2014, pepluspatru Association – Ivan Gallery, Bucharest, 2014.

[ii] It is important to mention that the artists exhibit regularly both in Romania and abroad (eg. Mumok, Vienna 2017; Jewish Museum, New York 2014; Istanbul Biennial, 2013; tranzit.hu/Budapest and tranzit.ro/Bucharest 2013; Palais de Tokyo Paris, 2012)

[iii] Hal Foster: The Artist as Ethnographer, in: The Return of the Real, MIT Press, Cambridge–London, 1996.

[iv] Raluca Voinea: Creating Forms of Poetic Justice, in.: Anca Benera + Arnold Estefán. Works 2012-2014, pepluspatru Association – Ivan Gallery, Bucharest, 2014.

[v] Taking and appropriating a more concrete but also symbolic object, which is well-known in the Hungarian (Transylvanian) folklore, is in the focus of the project We are all dust and ashes. After a workshop which took place during the first edition of OFF-Biennale Budapest in 2015, this year the artists – according to them – are “hijacking the folklore” by creating their “own” prototype of Kopjafa (a traditional Székely monument) with new designs which are representing repressed social groups.

[vi] They delegated the process of baking to someone.

[vii] Svetlana Boym: The Future of Nostalgia, Basic Books, New York, 2011.

[viii] Boym, 41.

[ix] Boym, 49.

[x] Quote from the artists, via email.

Flora’s residency in Bucharest was made possible with the generous support of AFCN and Balassi Institute – The Hungarian Institute in Bucharest.

POSTED BY

Flóra Gadó

Flóra Gadó (b. 1989) is a freelance curator, art critic and Ph.D. student. She graduated in 2015 from Eötvös Loránd University with an MA in Art Theory. Currently, she is enrolled in the faculty�...

artportal.hu/

Comments are closed here.