The “Touch Nature” exhibition, launched at the beginning of May at /SAC Berthelot and /SAC Malmaison, is a major accomplishment that explores the theme of nature in the context of the ecological crisis, involving an impressive number of Romanian and Austrian artists: Uli Aigner, Matei Bejenaru, Floriama Candea, Codruța Cernea, Adriana Chiruță, Ciprian Ciuclea, Larisa Crunțeanu, Anna Dumitriu & Alex May, Michael Endlicher, Thomas Feuerstein, Peter Hauenschild, Barbara Anna Husar, Nona Inescu, Kitty Kino, Aurora Kiraly, Alexandra Kontriner, Ana Maria Micu, Nicoleta Mureș, Klaus Pichler, Monika Pichler, PRINZpod, Oliver Ressler, Gregor Sailer, Elisabeth von Samsonow, Hans Schabus, Ramona Schnekenburger, Marielis Seyler, Paul Spendier, Oana Stanciu, Mircea Suciu, Dan Vezentan, Judith Wagner, Nives Widauer, Laurent Ziegler. Organized by /SAC Bucharest and the Austrian Cultural Forum, with the support of the Austrian Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs and curated by Sabine Fellner and Alex Radu, with an exhibition design by Justin Baroncea and Maria Ghement, it is part of a series of events initiated by Austrian partners, that have been or will be held until the end of the year in 11 European countries and the United States, culminating in a large event that will bring together participants from all 12 countries at the Lentos Museum in Linz.

Continuing a series of ongoing Romanian-Austrian collaborations that critically analyzed the natural-artificial relation as well as the concepts of „nature” and „landscape” and the capacity of contemporary art to (re)present them (see the Landschaft exhibitions at Fotogalerie Wien and Galeria Posibilă), “Touch Nature” proposes approaching nature as an experiential and imaginative encounter. Behind this interpretation is the 19th-century German explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt, today considered the father of climatology and ecology. In this sense, the title of the exhibition is linked to the way in which the Romantic, holistic thinking of the distinguished scientist overcame the Cartesian, mechanistic paradigm that reduced biology to a mechanism described by mathematical laws. As his comprehensive treatise entitled Cosmos demonstrates, Humboldt was inspired by ancient Greek thought, for which nature was more than a mere sum of parts or set of laws and classifications. For him, as for the Greeks, nature is rather a living, fascinating and complex animal, whose interconnected elements can never be understood by reduction to formulas, but can instead be experienced and appropriated by way of unmediated intuition. It is important to note that feelings constitute a part of this romanticized, experiential knowledge, guided by things themselves (den Sachen selbst).

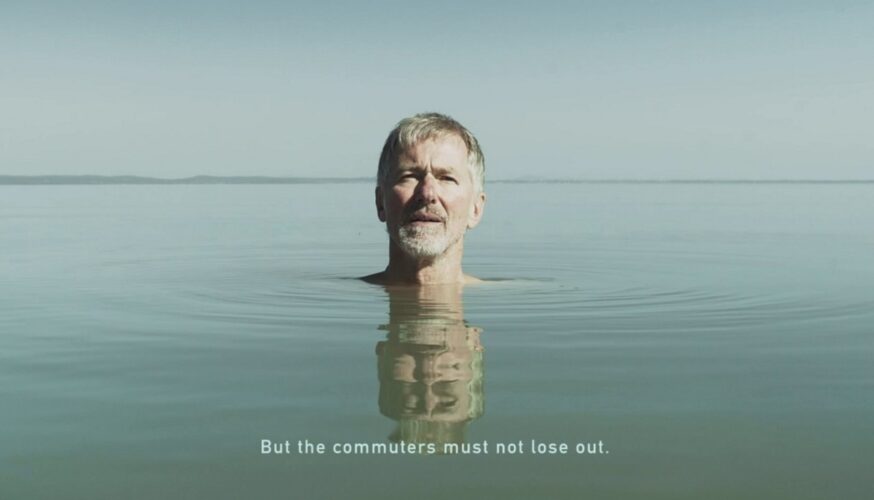

In this context, the works proposed by the “Touch Nature” exhibition confirm the importance of experimentation and emotional engagement by inscribing themselves in the realm of pure poetry, even if sometimes mediated by the camera lens. In Ritual for earth (2022), Barbara Anna Husar sets off on a diaphanous journey over snow-covered mountains with a red balloon of an unusual shape (the artist claims it’s an udder, but it could just as easily be a jellyfish or a flower). The aim of this journey is to release 1001 wishes for the earth created by children who have inscribed their messages on just as many leaves, thus entrusted to the wind and further on to the three streams that cross the Swiss Lunghin Pass. Pure poetry, but not in the sense of mere versification, are also the three subtle projections by Adriana Chiruță that bring to presence butterflies, lovestruck snails, or sublime snow-covered mountain heights. Displayed in unusual places, on ceilings or in usually overlooked passageways, they engage a gestural side, demanding the activation of the body: tilting the head, raising the eyes and the aching concentration of the gaze. unsettling blends of aesthetic categories, typically associated with the realm of nature: grace and cruelty, beautiful and sublime, the coldness of death juxtaposed with an excess of vitality. Marielis Seyler’s rug printed with graceful butterflies leads us towards the same vortex of poetry and feverish affectivity (compassion for the condition of nature, rebellion) as Ramona Schnekenburger’s expressionist portrait of a hybrid animal-vegetal creature and Nona Inescu’s plant sculptures, which strike a blow against anthropocentrism by replacing Rodin’s famous hands (La Cathédrale, 1908) with a cathedral of nature crafted from dry palm leaves. A similar critique of anthropocentrism is delivered by Michael Endlicher’s Dar Dar Dar, at first glance a contemplative shot of a cold, clear blue and tranquil lake, mirroring the clear sky without a single cloud. However, against the backdrop of the blue that discloses the absolute continuity between earth and sky, the human character notably emerges: a head submerged up to the neck in the natural element reciting in an even but sonorous voice a long series of possible objections to ecology and the renunciations it demands.

At the same time, “Touch Nature” aligns with the new paradigm of Eco-phenomenology, whose dynamic proponents such as Dylan Trigg or Ted Todvine draw attention to the multisensory nature of the environment, emphasizing the importance of positioning humans in a relationship of perfect symmetry and reversibility with the non-human. Hence, there is a profound understanding of nature’s rights, of the forest and landscape, to gaze back at us, thereby displaying its own capacity to feel, experience and even to wear a face. In this respect, a significant part of the photographs and drawings present in the exhibition are defined more as phenomenological approaches that are not interested in the classical production of re-presentations, but rather in the elaboration of detailed and concrete descriptions that can function as invocations or as bringings forth of nature with its authentic states and moods. One can read in this context the poetic Green Line collages by Larisa Crunțeanu, multiple black and white exposures that contrast natural and urban dwellings, as well as Elisabeth von Samsonow’s series of eco-feminist photographs that embody the revolt of a goddess covered in dry branches, personification of the desolate, infertile landscape.

A similar aesthetic is proposed by the six instances of the Văratec forest captured by Aurora Kiraly during an initiatory walk. Under the name of Reconnection, this trail reveals as many faces and expressions of the forest captured by a machinical eye behind which an artistic will is manifested. Despite the title, the immersive universe, encapsulated in a shell of branches and leaves, conceals an affective space devoid of sky and horizon, enclosed within itself, turned towards the earth. The photographs gain depth instead through subtle layers of overlaid text on an imperceptible layer of museum glass. The words here do not aim to compose poetry in the classical sense of the word. Alongside the images, they rather constitute lessons of seeing, showing us nature as a nature beyond human preconceptions and habits of ignoring the world and its inner layers, reducing everything to a few dichotomies and concepts. They testify to the presence of beauty all around us, behind every tree or blade of grass. It all depends on our way of looking, of touching (“Touch Nature”!). Aurora Kiraly’s forest seems alive, not only because in various frames it shows its limbs or even takes on a face, but because it is animated from within, because it looks at us in its own way with a thousand eyes or a thousand leaves.

The remarkable project To Heal You, I Hardly Know What to Do by Ana Maria Micu, an artist who masters drawing techniques so well that she allows herself to push them beyond the limits of representation towards a space of affect and performativity, also represents a meticulous artistic phenomenology. The subject of this observational drawing, as the artist calls it – what I would also describe as a phenomenological description – is a life experience during the COVID crisis. After a period of gardening on a limited perimeter balcony, the artist realized she had too much compost. The dilemma of abandoning this organic material, which she had nurtured herself, turned out to be a revelatory issue, raising intricate ethical, metaphysical and practical questions. Is compost living matter or is it merely waste? What is its relationship to contemporary high-rise dwelling far from the earth? Are bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms part of nature with a status comparable to that of Anthropos? Can we consider this dark matter, perpetually the source of energy and life, as unclean?

Among the most pertinent answers to these questions we recall George Bataille’s base materialism, which calls for a reconnection with the soil and the abject as a fundamental layer of being, the contemporary theory of the formless (Rosalind Krauss) and Jane Bennet’s new materialism. Ana Maria Micu’s response was not to release the compost anywhere other than in the forest and to document the process through photographs, that upon returning to the studio, became charcoal and chalk drawings. The almost ritualistic process consisted of an animation of 47 frames taken at successive moments during the drawing process on the same sheet of paper. Specifically, while the background of leaves and branches remained fixed, the artist intervened on the paper with chalk and charcoal, sketching and erasing the character’s movements one by one. Thus, as soon as they were photographed, the successive drawings disappeared, ultimately giving rise to a final image, the last frame of the animation and also a drawing, exhibited face to face with it. We note that this ingenious process generates pertinent comments on the relationship between drawing and photography: Who documents whom? Which is the copy and which is the original?

In a similar manner, Ciprian Ciuclea expands his critical research on the ongoing deforestation of the Băneasa forest with a new chapter. This time the focus is on how the forest’s nutrient-laden soil is being stripped and left to become infertile and barren, like the lunar soil. Within the extensive photographic documentation, one of the pictures shows precisely this perimeter of emptiness into which a small anthropomorphic statuette has been inserted. The adjacent depiction of a similar image taken on the moon by the Apollo 15 expedition suggests that this is in fact a re-enactment of the performative act in which the Apollo space program crews deposited a series of artificial objects on the moon: the American flag, a bible and, in the case of the Apollo 15 crew, a miniature astronaut statuette by the Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck. The debate in the early 1970s about the statue, which for NASA symbolized a fallen astronaut and for Van Hoeydonck the achievements of humanity with a capital H, without gender, race or nationality, is being reiterated in the Anthropocene period as the relationship between man and nature is redefined.

The same human-nature connection is also addressed by Dan Vezentan’s long-term research on the process of phenomenological dwelling on the earth, under the sky, in balance with the elements of nature. Vezentan presents a documentation of his working process and a model of the Harvesting Structures series, large-scale cellular assemblages of crates or baskets for collecting fruit, vegetables or other agricultural products. Putting into action the important ideas of Ursula Le Guin (The Carrier Bag Theory), the artist draws attention to the predominance of agricultural tools over weapons, of the feminine element (Gaia) over the agonal masculinity, and to the original kinship between technology and nature.

The poetry of dwelling blends with activism in Oliver Ressler’s remarkable investigative films. To this end, Ancestral Future Rising juxtaposes images of raw beauty (rainforests, effervescent waterfalls, stones covered in mysterious petroglyphs) with interviews of residents and activists in and around Quito Canton, an area of Ecuador, declared a UNESCO natural reserve. Despite the global warnings of scientists (starting with Alexander von Humboldt in the 19th century) and ignoring the fact that the unique ecosystem inhabited by hundreds of mammals, reptiles, birds and amphibians also harbors ancestral cultural remnantsancient of the Yumbo and Inca peoples, the government has approved concessions for gold, silver and copper mining. Against this tense backdrop, Ressler’s film shows how nature and culture have the opportunity to join forces to stop the regime of exploitation: from ceasing dynamite detonations at depths that could alter both the history of the relics and the course of rivers and the life of forests, to the simple call to let things be.

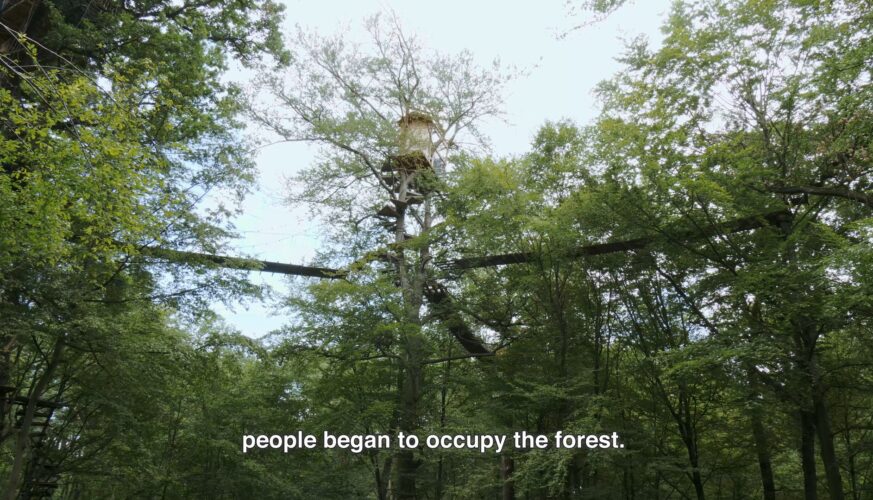

The second film, titled The path is never the same, reaffirms the need for a profound continuity between nature and culture. The concept of nature is inherently problematic, inevitably creating ruptures between the realm of the living and human creations, comments one character, expressing a desire to become one with nature, even at the cost of dissolution of the concept itself. The issue of the confrontation between wilderness and anthropocentric exploitation interests is also revisited, this time in the context of the Hambacher Forest near Cologne, one of Germany’s last old-growth forests. In an attempt to halt its deforestation and the exploitation of its lignite reserves, from 2012 until 2020 (when, after prolonged pressures, the government agreed to protect areas that had not yet been destroyed), around 200 people initiated one of the most original occupy strategies here, building shelters in trees between sky and earth. The powerful metaphor of dwelling can be read in this context, both in political terms as a liberation of space and the creation of heterotopias (Foucault), and phenomenologically, in the sense of the pulverization of space into „places of dwelling” (Heidegger), dense zones not subject to spatial leveling imposed by positivist thought or the capitalist circulation of commodities.

Ressler’s film masterfully presents this rewriting of space, the generation of liberated places of dwelling through long, panoramic shots. These carefully and patiently follow the rope bridges that connect the tall trees, the squat huts of activists, the games of suspended strings and lights that cut and reorient the region of the Hambach Forest. From this, we understand that ‘up’ and ‘down’ are mere conventions, simplifications that don’t reveal much about the true nature of space, its multidimensionality, or what it means to dwell on the earth yet close to the sky. These shots are complemented by ground-level footage that gently exposes an ant’s way of looking and reveal how the sky can be seen through the leaves from the height of a mushroom cap. Time passes differently here, each moment is full, every gust of wind is significant, every sway of grass and leaves means something. It is about qualitative, kairotic time, impossible to measure, about the „celebration of finitude” that eco-phenomenologists associate with the intensification of the concrete, perceiving the infinite within the finite.

Last but not least, “Touch Nature” exhibition extends the hypothesis of nature-culture continuity through several captivating artistic endeavors in the interstitial zone where the biological meets the artificial and the technological. Examples include Oana Stanciu’s poetic digital exercise imagining a garden of the Anthropocene, and Nicoleta Mureș’ collages of black and white avatars, neon mushrooms and withered real plants, scanned through photogrammetry. In this context, we can also include Thomas Feuerstein’s fascinating installation, Octoplasma, a white, almost translucent creature grown in a formalin jar from human liver cells, an uncanny hybrid between a liver and an octopus.

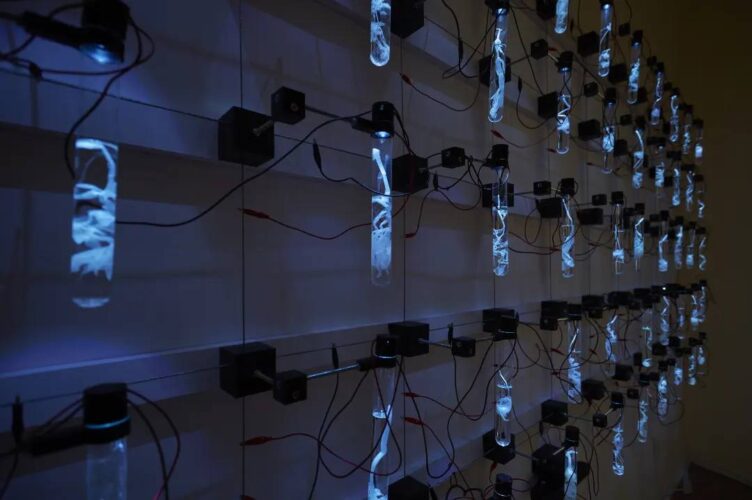

Two other projects that dominated the spaces of Berthelot and Malmaison can also be placed under the same domain of the poetry of strangeness. At Berthelot, we are talking about Floriama Cândea’s spectacular installations, Endangered order and Sensitive Dependence, poetic exercises in the technological appropriation of movement, breathing, natural rhythms, flow and duration. These projects fall under the umbrella of BioMedia – an eco-art practice promoted by Peter Weibel, which eschews the use of biological materials in favor of employing technology to simulate typically natural behaviors and explore life. While Endangered order simulates the rhythmic signalling of fireflies already extinct in many natural perimeters, represented by 50 luminous test tubes, Sensitive Dependence involves a series of transparent glass globes housing hybrid plants – white leaves with fine silicon veins and compact, black flowers – that can be activated by human touch. Specifically, in this second case, using an assembly of pulse oximeters, cables and Arduino boards, Sensitive Dependence transforms the viewer’s heartbeat into a flow of vegetal energy that animates the plants, making the white leaves pulsate and the flowers breathe like lung tissue trapped in a black cloth pleura. Returning to the first case, Endangered Order uses a depth camera (Kinect) to detect when someone enters the depth field of the installation and consequently disrupts the LED pulses of the 50 firefly test tubes. The presence of human intruders thus causes a loss of natural order, disorganizing the rhythms and light pulses, while their absence allows for a gradual resynchronization until all the fireflies light up in unison again.

It is important to note that at the origin of these entities is the procedure of decellularization, used in biomedical engineering to isolate the extracellular matrix of a tissue (ECM) from the cells it hosts. In other words, Floriama Cândea’s fine silicon strands invoke the idea of a decellularized leaf that retains only the body’s formal matrix: the white, almost translucent connective tissue. It is interesting to see that this biological scaffolding on which bodily functions rest brings us paradoxically close to what Aristotle would have called the „form” of the leaf. We have to admit the power of art to propel us unexpectedly into a twilight zone where the metaphysical touches the biological, the human returns to the vegetal and the becoming-plant (Deleuze) seeks the idea (Plato).

At Malmaison, the latest work addressing the theme of the botanical intertwined with the artificial is Modele, a series of large-scale photographs by Matei Bejenaru depicting a fascinating range of simulacrum flowers. Despite being displayed at the back of the hall, they caught your eye right from the entrance. Remarkably, the foundation of these photographs lies in a set of small botanical models imported from the GDR in the 1970s-1980s, a set recovered by the artist from a laboratory at the Faculty of Biology in Iasi. The project reveals a series of constants of the artist’s conceptual laboratory: a readiness for research and a structuralist interest in investigating the machinic eye, contrasted with the organic need to launch inquiries into affective spatiality that are not quantified in meters but in sentiment and color. In this context, Matei Bejenaru’s flowers can be seen as a manifesto of the hybridization of the botanical with the animal, the human, and, last but not least, with the mechanical. Magnified and viewed from unexpected angles, the voluptuous petals, the flesh-colored corollas, sap-dripping calyxes, and the bleeding white pistils thus invoke human or animal organs as well as menacing mechanisms, sublime machine flowers. In these giant cyborg-flowers we encounter a new species of the sublime that borrows the terrifying mechanism from the old Kantian sublime, the dynamic sublime of nature. What is invoked here is not the gracefulness of the botanical but rather its power.

Placed at the interference of the natural with the artificial, of the real with the virtual in a world of contrasts and affinities, Floriama Cândea’s fireflies and cyborg plants, Matei Bejenaru’s models, Thomas Feuerstein’s liver-octopus hybrid, Oana Stanciu and Nicoleta Mureș’s digital garden and flowers escape any traditional classifications and norms. Together with all the other projects in the “Touch Nature” exhibition, they propose rethinking the world beyond genres and species, according to new categories and focal points that belong to art (shapes, sounds, colors) and the everyday (things, technologies). A new type of ontology is inaugurated: visual, capable of understanding hybrid modes of existence, natural-technological. To transcend solipsisms and dichotomies that have isolated humans from their world and things, this ontology initially pursues the phenomenological premises of reintegrating humans into the world and reclaiming things themselves. However, these are rethought beyond the rigid functionalities of anthropocentric perspectives, from within the new technological rhizome – the IoT Internet of things. In this case, technology questions our capacity to act upon the world, to protect the sky, earth, to approach plants, fireflies, and all other things until they become our own bodily extensions.

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.