The Hognon family has been traveling the roads of southwestern France for more than thirty years, staging plays that explore their nomadic Tsigane identity—“Tsigane,” in the French context, being a positive word generally used to encompass the country’s three Roma subgroups: Sintis/Manouches, Roms from Eastern Europe, and Kalés/Gitans. The family is breathing life into an ancestral tradition that was all but lost: troupes of itinerant entertainers bringing art and intercultural communication to rural areas.

*

“For us, being nomads means more than driving our caravan from one village to another. It’s also a spiritual and intellectual nomadism,” says Marcel Hognon. “By writing plays, I am endlessly exploring this nomadism of ours so that it may be handed down to the next generation.” Like his father and his father’s father before him, Hognon was born in a caravan by a river. His ancestors are members of one of the oldest Sintis/Manouches nomadic families in France, who worked in iron forging and basketry. His father was a street performer who introduced his children to the art of performance.

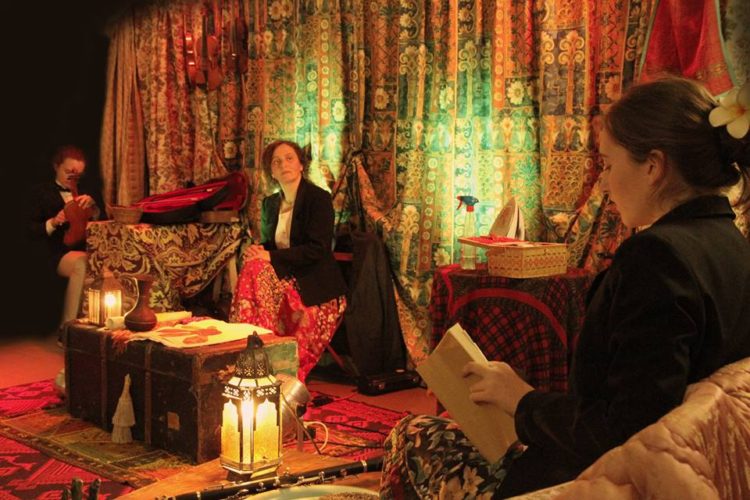

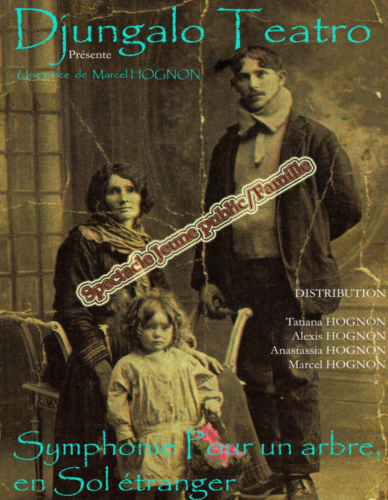

Hognon began as a musician, later becoming a visual artist and then a playwright and actor. Thirty years ago, he and his wife Anastasia, a Greek Tsigane, founded Djungalo Teatro, which means “villain theatre” (referencing Molière’s L’Illustre Théâtre) in Romani. They began by putting on puppet shows, then the plays that Hognon was writing. With the caravan as their backdrop, or under a circus tent, the couple performs with their two youngest children, Alexis and Tatiana. The family also formed a music group, the Sinthan Tchavé (children of the land of Sind), which sings their “bohemian” melodies. Their plays and songs take audiences on a journey through the Tsigane culture and traditions.

Theatre as a Way of Telling Your Own Story

Hognon tells us that an estimated two hundred to three hundred Tsigane families used to travel across France, putting on dance performances or music or theatre productions. “All that art disappeared when the Tsiganes were sent to concentration camps in World War II,” he says, “but also, and this is less well known, during World War I.” He mentions this moment in history in his play L’être bohème (The Boheme Being), which explores the origins of hatred toward his people.

Because Tsiganes have an oral tradition, it is hard to find written records of their performances. Most of the historical evidence on them is from outside works, which perpetuate the stereotypes that range from fascination to repulsion. In French literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Tsiganes are seen as kidnappers, fortune-tellers, or fantastical bohemians—nomads running free. The author Blaise Cendrars, however, tried to document the reality in his poetic autobiography, mentioning his Tsigane friend Sawo. “It was 1916, I had just returned from the front. I had followed the caravans of the travelling theatre,” he wrote in his book L’Homme foudroyé. “My friend Sawo [was] accompanying us part of the way, but without pleasure; he loved only the streets of Paris and the life in the caravans.”

Hognon is convinced that dramatic literature already existed in the art of his forebears. “This knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation doesn’t come out of thin air. I can’t imagine that the desire to assert themselves as Tsiganes was foreign to them.” So they must have written their own story. This is one of the reasons why Hognon writes and publishes his plays—to leave behind a written trace of his search for his identity and that of his family. “Today, we have this fantastic tool called the internet that allows us to preserve all that, something my ancestors didn’t have,” the playwright adds.

Part Hybrid and Part Lesson—the Originality of Nomadic Creation

Author Stéphane Labarrière describes two types of nomadism in his book on itinerant performance, Spectacle vivant à l’épreuve de l’itinérance: nomad artists and sedentary-mobile artists. He sums these up in the concept of structif, which studies the influence of daily life, including economic and material aspects, on performance. “The approach is different. The sedentary-mobile person is mobile only during the show,” he explains, “while the most important thing for the nomad artist is being a nomad. So that has an effect on the creative process, because daily life is part of that process.”

This is why the family component is so important to the nomad artist. Hognon writes the plays for Djungalo Teatro, but he writes them by taking into account the members of his family. They all do the readings and the acting together. And learning occurs by immersion: the children learn on the job and the show is part of that learning, and vice-versa. The same is true of the Cirque Romanès, a Tsigane circus in Paris. The children play the roles even though they are not considered to be professional actors. Their performance is part of their training, and the show changes in step with their progress. As Labarrière describes it:

“This is what makes nomad art original. If you are a sedentary-mobile artist, you are mostly going to create a new show starting from nothing. If you’re a nomad, you see a continuity, and even if there are new shows, you can see what was handed down from one generation to another.”

Hybridizing artistic forms is also part of nomad art. Even though this cross-pollination is not specific to the itinerant artist, it is part of their artistic identity. For example, Hognon is a guitarist, visual artist, playwright, and actor. His wife makes the costumes and plays the tambourine, while their children play violin and clarinet. Next summer, they will stay three days in each village for their Odyssée Bohème: Chant III (Bohemian Odyssey: Song III), a show in three acts about the daily life of a nomadic Tsigane family in France. The first part is mainly dramatic, the second is both dramatic and musical, and the last is musical only. “I make distinctions between the art forms but I don’t separate the genres,” explains Hognon.

The “Invisible People” of French Theatre

Unfortunately, this desire to explore the traditions and the arts of the Tsigane comes into conflict with French institutions, which are often unwilling to embrace the affirmation of a nomadic Tsigane identity. The French constitution defines the republic as “indivisible,” which means it does not recognize regional and ethnic minorities. This translates into increased oversight of these minorities when they try to take back their cultural identity. Last summer, the French police interrupted a Djungalo Teatro performance to check papers. Hognon took a picture and sent an official request to the UN to protect the Tsigane population in France.

The physical act of roaming is also hampered, because Tsiganes must obtain municipal authorization to park their vehicles. This winter, the Hognon family set up its caravan between Bordeaux and La Rochelle to work on plays they will be presenting next summer. But this is also the time when they have to apply for parking permits. “It takes a great deal of time,” says Hognon. “Before, we would perform one show per night in each town, but we had to fill out two hundred applications. Staying three days has allowed us to cut down on applications.” Still, the family has to fill out twenty or so applications just to obtain one authorization.

Tsiganes arrived in France in the fifteenth century as nomads. They slowly became more sedentary, at times by force. Several hundred families were still nomadic before the two world wars, but most of them were sent to extermination camps or made sedentary in the 1950s. Today, families like the Hognons are continuing their nomadic tradition. The administrative code defines them as “travelers,” which includes Tsiganes and other types of traveling carnival workers and itinerant traders. In 1969, a travel pass was created for those who were not sedentary. Although they were French, they had to report to the police station on a regular basis. The pass was not repealed until 2016, when it was ruled unconstitutional because it prevented freedom of movement.

Yet nomads continue to be stigmatized. “We are always being hounded. We receive no assistance, no special favors,” objects Hognon. In the 1990s, he founded the Mouvement Intellectuel Tsigane (Tsigane Intellectual Movement) and the Comité International de Réflexion Tsigane (International Committee for Tsigane Considerations) with some other Tsigane artists. “We worked well for a dozen years, and then it all fell apart in 2010 under President Sarkozy’s repressive policy against Roma and Tsiganes. The repression continues today but the general public doesn’t see it,” he adds.

While doing his research, Labarrière noticed how these nomadic artists had become invisible. When he wanted to write his thesis on itinerant theatre, university officials and heads of institutions that support the arts told him: “We don’t know about them. They don’t exist.” Yet they do, in fact, exist. They just have to organize themselves on their own, outside the system of subsidies and festivals. While Djungalo Teatro has been able to obtain creative grants, it does not count on this aid alone, because “you can wait months before receiving them and sometimes they lose our applications,” laments Hognon. Nor does the company hold the status of “occasional performers” because they have not accumulated enough hours. Before taking to the road in March, the family lives off concerts, sculpture sales, and income saved over the summer. Other itinerant artists do odd jobs to get by.

Nowadays, references to nomadism can be seen everywhere, like digital nomads and the bohemian lifestyle. People are fascinated by nomads, but the true nomads are disappearing. Labarrière describes this ambivalence: “The image of the nomad has been taken over by marketing departments. We see nomads in movies, in shows, we praise the nomad lifestyle in magazines, but we reject those who really want to live as itinerants.”

Itinerant Theatre That Promotes Intercultural Dialogue

Despite the denial, nomadic theatre has always been a part of the French artistic scene. In the seventeenth century, Molière, like most actors of the era, began by playing in a traveling troupe. He also spent time with Tsiganes during his wanderings and had “Egyptians” (the word used before “gypsy” to describe Roma in France because people thought they came from Egypt) in his plays. Up till the 1970s, people in the provinces regularly saw theatres and circuses set up in the town square. Everyone would go to see the show. An article in the Libération newspaper from 1996 recalls this bygone era of the traveling theatre as the “provincial theatre,” often scorned by the Parisian theatre scene.

“Sadly, all that became very rare,” explains Labarrière. “First because culture became institutionalized, ruining the autonomy and the authenticity of the traveling show and making it dependent for its financing, but also because everything has been covered over in concrete and there is no room for itinerant circuses and theatres except outside the cities.” One concrete example of this is the installation of “traveler sites,” parking areas that every municipality has been required to set up since 2000. The arrangement forces the non-sedentary people to park outside the towns, often next to waste recycling centers or water treatment plants. Labarrière feels that television also led people to abandon the itinerant theatres. “People used to go out at night back then, but now they stay home to watch the show.”

But traveling theatre does have its place in French drama while also providing an artistic alternative to traditional drama. This became clear at the Centre International pour les Théâtres Itinérants, where several companies, including Djungalo Teatro, gathered to share experiences and preserve their originality in the world of entertainment.

“Once a reporter described us Tsiganes as coming from nowhere,” Hognon says. “But we don’t come from nowhere! We’ve been in France for centuries and you become part of the land.” This reveals the unique nature of itinerant theatre artists: they are familiar with the land and establish a special relationship with the locals. “Our nomadism is also spiritual because we return to the places that our ancestors have already passed through. It is a form of spirituality linked with memory,” adds Hognon.

Labarrière has also studied the nomad’s route in comparison with that of the sedentary-mobile artist. “When the nomad travels, he doesn’t go from point A, his house, to point B. His house is with him and he returns to the places he went before,” he explains. “Traveling artists know the land, they have guide posts, resources, and people who can help them. That’s not the case with sedentary-mobile people. They don’t know the areas and will go looking for outside resources like festivals.”

So the nomadic artist builds his lifestyle around his ties to the inhabitants and their lands, especially in rural areas that have been left behind economically and culturally. “Today, we have a dominant culture that does not come from the people so it is not made by the people,” says Labarrière. “Itinerant artists are necessary because they come in direct contact with the public. They provide a sense of togetherness and intercultural dialogue.”

Through theatre, Hognon is rediscovering an oral tradition and a direct language based on his own way of seeing things. It is a direct art that is “translated live. There are no more obstacles, no more bans. You’re on the stage and you don’t need to shout or make demands,” he asserts. “The artist channels other intelligences, those of the audience but also of elected officials, who will change their perceptions about us.”

One specific example is the use of the word “bohemian” applied by people outside the Sinti/Manouche families. But Hognon and his family have chosen to use it. “When we give the word a new meaning, we give our identity a new meaning. We choose ‘bohemian’ because it describes our work, which is artistic and poetical,” he says. “Even though there is an element of activism to our theatre, there is also a feeling of the pleasure of writing and communicating with others through theatre. We want to explore our own universe rather than impose a point of view.

Their efforts have paid off. In November 2018, their play Lettre à la Poule (Letter to the Hen), the story of a nomadic Tsigane family that faces xenophobia, won the audience award at the International Prize of Il Teatro Nudo di Teresa Pomodoro in Milan. In the play, a tree tries to heap clichés on the family. The family, sitting in the village square, has no intention of being boxed in by stereotypes.

The award serves as a first step toward European and international recognition, which Hognon approves of. “I am noticing the emergence of Roma theatre across Europe. That’s great news,” he says. He is also in touch with Roma companies and actors in other European countries. In this way, the theatre is becoming a way of writing a new “collective story” of the Roma people. “Nomadism is physical and spiritual, but also temporal,” he says, “because these texts, this work that we do, becomes part of our history and the history of a country and a continent.”

This piece originally appeared on HowlRound.com on 13 March 2019.

POSTED BY

Marine Leduc

Marine Leduc is a freelance journalist in France and Romania. Before going to university, she hesitated between two paths: journalism or theatre. She took the first one, but the second one has always...

Comments are closed here.