Recently, a renowned British artist posted a letter from a child on Instagram declaring that his paintings make her happy. A commenter responded that this was more valuable than any sort of art criticism.

Maybe we have reached the point where the question of ‘likes’ has entered so deeply into the professional life of artists that the traditional system of art producers, distributors, critics, and audience no longer holds — and does not provide any meaningful corrective measures to what artists are doing within it. And though this lament may sound outdated, so many of us have not stopped believing that art might still carry some kind of value. Witnessing every aspect of art swallowed by capital, some of us still believe in art’s agency. “If art could change the world” reads the blurry cursive font of one of the paintings in the latest exhibition at ElectroPutere in Craiova; another proclaims: “Too exhausted to grasp beauty”. But how can we overcome this dichotomy of agency and form?

The exhibition The Resilience of Capital can be read as a continuation of Silvia Amancei & Bogdan Armanu’s practice of tying these two threads together ex negativo. In multiple past video works, they have shown how global power structures and access to financial means shape the possibilities of their artistic practice, turning the two artists into powerless subjects on the margin of this capital-driven world. Though they exhibit internationally, the “resilience of capital” still casts a shadow over their practice. Disseminating their work does not change or do anything but garner some affirmation within a bubble. Agency and attention still follow money. Maybe this is what led to SABA’s first show of only oil paintings, seemingly imitating the kind of exhibitions that have impact in the art world.

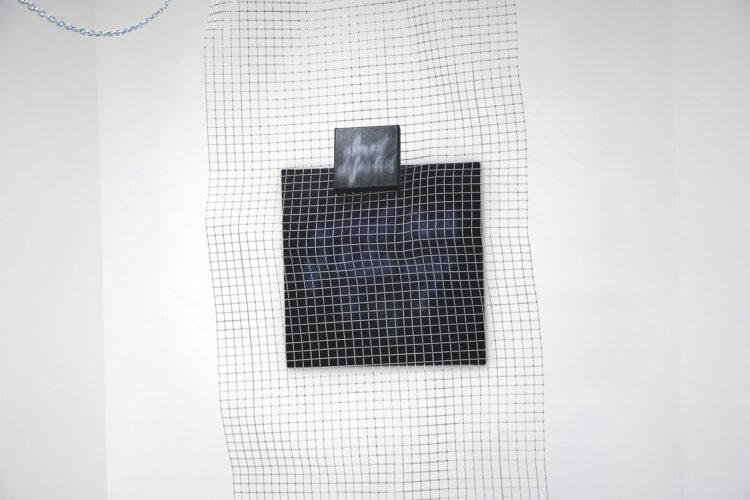

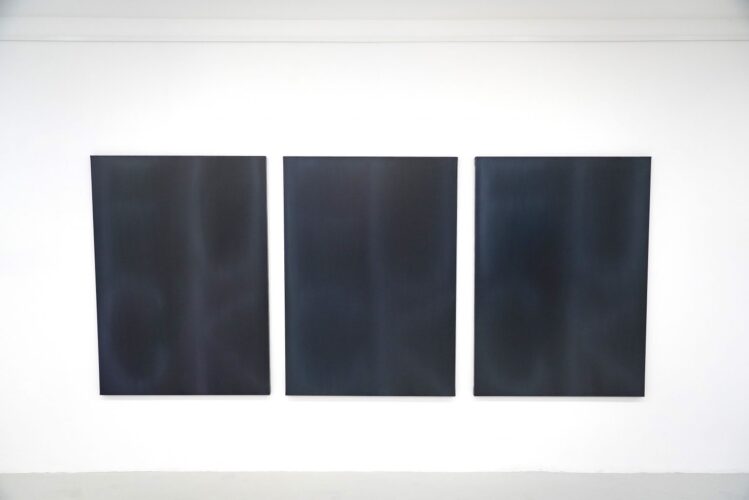

Despite its (former) site-specific dedication as the museum of Craiova’s theatre and its unusual shape, the exhibition space still comes across as a white cube; SABA’s black canvasses only emphasize this reading. Neither hung in straight line nor all the same size, still their sheer presence and stark contrast to the white walls present a perfect art-world presentation. Detached from the walls, two metal grids serve for the mounting of further black paintings. The bent-out-of-shape grids could be read as a metaphoric second space within the first, like the outlines of 3D renderings that have not yet been filled in with color suited to the landscape or surfaces they are supposed to illustrate.

These two spaces are replete with messages: the large paintings with capital letters drive home a sense of resignation, aggressively turning against the system called “art”. The most direct is a triptych stating “FUCK” on each of its 1 by 1,40m canvases. The others claim the artists to be both powerless and hopeless — tropes that SABA have been dealing with for some time. What is interesting is how by putting these words in uppercase letters across the width of the canvas they reduce the entire exhibition’s statement to these sentiments about the artworld.

But there is also a softer side to these declarations, a hint to SABA’s hidden desires, a feeling that they wished to erase from this show. There are canvases that speak of beauty and faded dreams, like “Seamlessly falling into melancholy”. Mostly these are hung on metal grids or from chains detached from the walls. And though this way of mounting adds rigor, even evokes S&M practices, they reveal a tiny remaining spark of belief. As these paintings turn into another empty gesture of revolt against the very system within which they gain meaning, this is exactly how they gain power: by acknowledging that they are powerless. Explicitly pointing this out by assuming — and accepting — the little impact art has; the paintings turn into a kind of negative dialectics that inhabits the normalized form with its critique.

And yet, the most beautiful irony would be if these works would sell out and become a true market success. I’m not sure if it is about knowing your “enemy” or just another love-hate thing, but there are many instances when critique has been subsumed by the system. Yet is this the kind of “confirmation” one should strive for or just another layer of the idealist’s masochist dream to simply conform? Not everyone can be like Damien and embrace this joy. The anger emanating from SABA’s paintings is probably the more appropriate reaction of those who truly believe in the impact of art — even though they wouldn’t want to hear that.

n.b. The reference to the Instagram activity of the renowned British artist unveils the friendship between the artists and the author which manifests in the critical exchange of posts and memes on the absurdity of art and life. And this reference becomes even funnier knowing that their preceding series of paintings with similar content was as colorful as the British artist’s latest works. Our jealousy concerning his nepotism being more successful than ours just adds a drop of bitterness to this article.

POSTED BY

Maximilian Lehner

Maximilian Lehner works as a research and teaching assistant at the Institute of Contemporary Arts and Media at KU Linz and co-founded The Real Office (RO) in Stuttgart, an agency for concepts, fundi...

Comments are closed here.