When I hear the year 1984, George Orwell’s dystopia immediately comes to mind. Those of us who consciously witnessed 1984 were truly relieved that not much of Orwell’s surveillance and repression fantasies were real. In retrospect, we were mistaken, naive in thinking we were safe, and that only applies to the citizens of the free states. In the so-called Eastern Bloc, especially in Romania, there was a state of spying and surveillance, the obscenity of which would have surprised Orwell himself to a certain extent.

For me it is a dialectical task to write about Ceaușescu’s Romania. I was born in a free state, in the belief that the last terrible dictatorship invented by an Austrian was so fatal that similar things could not happen again during my lifetime. Nevertheless, I have a strange feeling when I consider the absurdity of dictatorships, Ceaușescu being one of the best examples, to be remarkable.

In recent years, I have become increasingly interested in literature about dictators. Perhaps influenced by my travelling exhibition stations in Eastern Europe, but certainly also out of fear for the ever more intense shift to the right in Austria, throughout Europe and the world. First it was the Refugee Movement 2015, now the Covid 19 crisis creating the circumstance, as well as the appearances of small men striving for absolute power. (Small Men is my personal framing for dictators or those who want to become dictators.)

This is exactly what surveillance does: you stop being yourself and start living next to yourself. The human being is unchangeable, but it can be forced to a degree of self-consciousness that is unnatural. (Patrick McGuiness).

But back to Romania in 1984 and the architect and artist Horia Marinescu, whose artworks are part of the exhibition The Romanian 1984, which took place in Vienna, at the 12-14 Contemporary gallery in June 2020.

Horia Marinescu is an architect who separates the drawing from the design process and allows it to become independent. Born in the Bucharest of 1967, he moved to Vienna in 1992. He grew up in Bucharest’s artist and writer milieu. Marinescu studied architecture in Bucharest, then in Vienna at the Academy of Fine Arts and the Technical University. He has always crossed the border between practical design, art and architectural journalism. He has maintained lively contacts with the Bucharest scene, bringing about the cooperation with Zeppelin and Ideilagram.

Zeppelin is the leading Romanian architecture magazine, published in Bucharest since 2008 (respectively 2000-2008 as Arhitectura), headed by Stefan Ghenciulescu, Cosmina Goagea and Constantin Goagea. Ideilagram is a Bucharest based association dealing with architecture and the city, implementing micro or macro ideas for urban communities, an interdisciplinary network for interventions in urban space, under the direction of Ilinca Paun-Constantinescu.

The exhibition The Romanian 1984 showcases, on the one hand, a survey of social and urban planning parameters (through the project Uranus Now by Zeppelin / Ideilagram), on the other hand Horia Marinescu’s confrontation with his own past and the experience of the demolition of his home and district. Uranus Now was conceived by architect and cultural manager Dorothee Hasnaș. She is the curator of the Street Delivery event on behalf of the Romanian Order of Architects and moderates București Cotidian, a live show about life in the capital’s neighborhoods, where the guests are locals and specialists in various fields.

During the restructuring plans and implementations that Comrade Leader elevated for his personal monument, the Marinescu family, like 30,000 other families, lost their home. Ceaușescu’s lofty reconstruction plans imitated the restructuring plans of Eugene Hausmann in Napoleon’s Paris, but with a communist twist: strictly geometrical streets, new blocks of flats and residential towers in kitschy style, cheap prefabricated housing in the suburbs, while senseless magnificent buildings lined the boulevards, which were obviously designed for parades and marches. The size of the buildings were to eclipse any human manifestation.

Since the beginning of the gigantic construction projects in the early eighties, the demand for marble and stone for facades and interiors had been steadily increasing. In the cemeteries the graves were therefore marked with wooden boards, table legs, chairs and even broom handles. Ceaușescu’s new Palace of the People could be measured not only in square meters but also by gravestones. Under other circumstances this would have been surreal, but unfortunately it was the only available reality. (Patrick McGuiness).

As a consequence, rural communities were forcibly resettled in concrete castles on the outskirts, families were torn apart, civic structures destroyed, people expropriated, crammed into tiny apartments, often without electricity, water or windows.

The photo from 1984 by Emanuel Tânjală is particularly striking – in which a young couple poses on a kind of pedestal, like a monument. The last remaining roots in the demolition landscape stand on the concrete manhole cover, which stands out of the rubble like a relic. The social and emotional wound, opened up in the people of the city after the dictator’s arbitrary interventions, has not been closed until today. After reunification, the new Romanian state withdrew from any responsibility and left the battlefield of property disputes to the victims. The climax of these absurd building projects was the Palace of the People. It was never explained what benefit the people would receive from this palace, but it was clear that this construction was designed to last for eternity. More floors go down than up, although it is impressive when you stand in front of it and feel like an ant, due to its dimensions. The underworld of the palace is supposed to be a universe in itself.

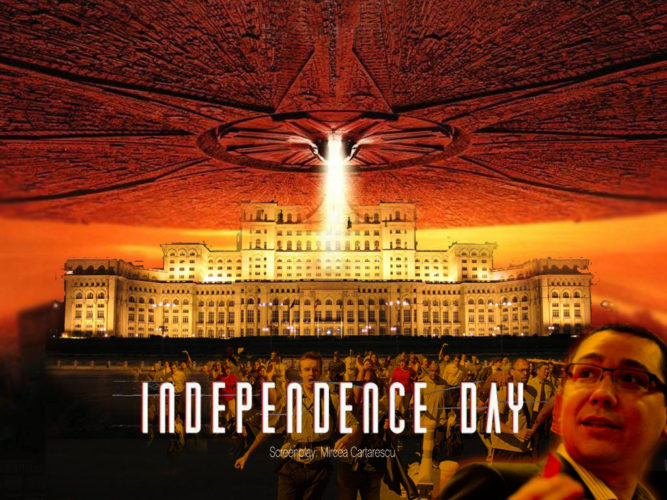

Viewed from a distance, the building resembles a plan of a mad world ruler in a Bond film, who installed bunker-like parallel universes underground for the case of emergency. To complete the caricature, the architects of the time took the opportunity to build “the largest post-modern ensemble in the world,” at a time when this style was causing a worldwide sensation. The Palace of the People became a conglomerate of all sorts of stylistic quotations, mixed according to the good humor of the communist leader, who, as is well known, was almost illiterate.

Modernism and populism, between Vienna and Bucharest

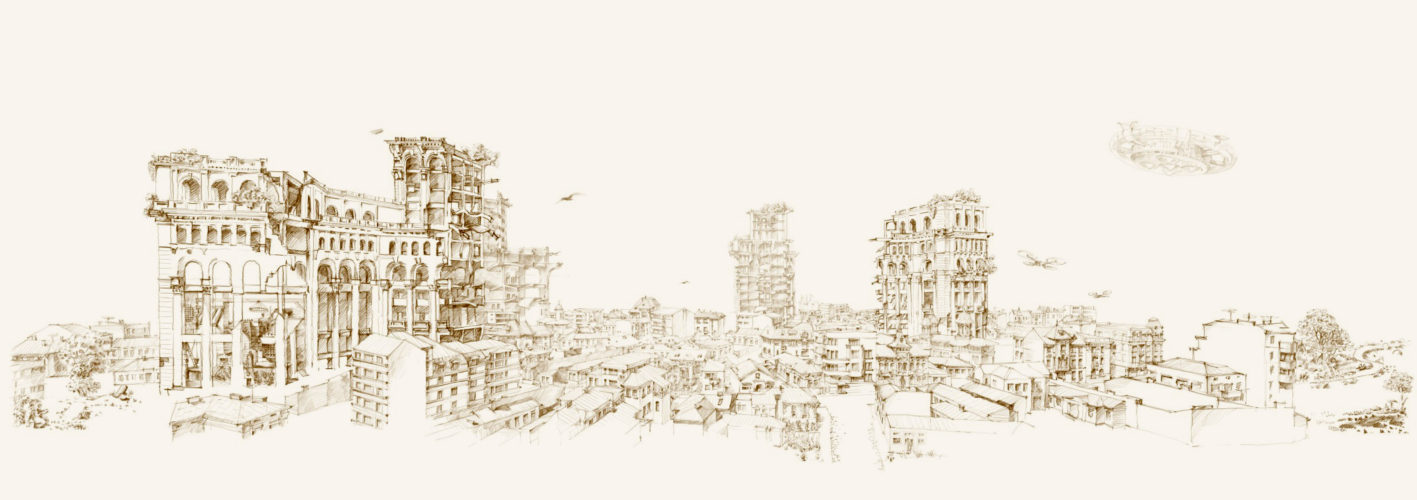

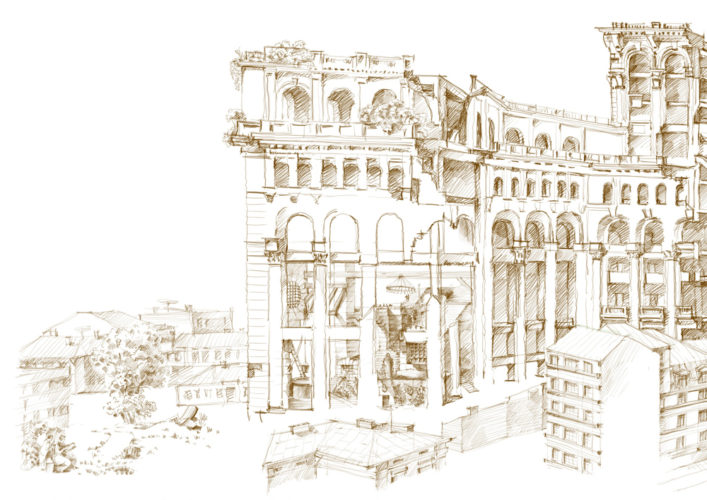

Exorcism through drawing is one of Marinescu’s approaches. Inspired by Mircea Cărtărescu in one of his novels, where he destroyed the Palace of the People in an apathetic scene reminiscent of Hollywood’s Independent Day, Marinescu takes this imaginary destruction as his starting point in his exorcism of drawings of the Palace of the People. He uses architectural set pieces of the same postmodern approach that was used during construction. Romantic ruins after Claude Lorrain, cellar scenes à la Piranesi or the detached dream-like state of Tarkovsky’s Solaris or The Mirror are added.

In 1992, Horia Marinescu set out to achieve a better, freer life and emigrated to Vienna, Austria. In 2000, Austria moved into an authoritarian, international right-wing corner and was rightfully criticized by many states for the newly installed vice chancellor Jörg Haider of the Black-Blue Government Phase 1, under chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel. In any case, the year 2000 marked a continuous movement towards neo-liberal autocracy in Austria, which reached its climax (so far) with the current chancellor. From the rain into the fire, from a dictatorship into a kind of corrupt authoritarian state.

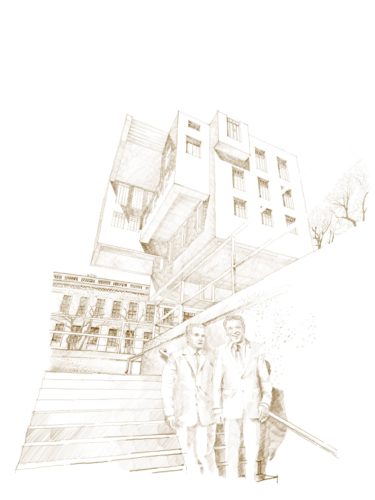

But what do Nicolae Ceaușescu and Jörg Haider have in common – except for January 26, their shared birth date? One is a dictator, the other is striving for it. Ceaușescu preferred people who resembled him: semi-educated, uncouth, cunning in a primitive way and rock-solidly faithful as well as thoroughly corrupt. Haider’s followers also were similar to him: young, dynamic, male, semi-educated, vain, devious, absolutely loyal and corrupt through and through. Both promised the best for the people, both left scorched earth in their wake. The after-effects are still felt today. In his digital drawing Nightmare Wittgensteinhaus, the two leaders stand amicably next to each other, Haider laughs as if Ceaușescu had just told him a joke. Above them hovers the upside-down Wittgenstein House, an example of pure, simple, ingenious architecture.

In the second perspective, Marinescu seeks a poetics with which to express his transformation from communism to neoliberalism, modernity and arbitrary change, from Ceausescu to Haider, from Romania to Austria. This inverted modernity becomes a reflection of postmodernism, which is not meant stylistically, but ethically and socially as a loss of orientation.

The exhibition makes one curious to dig deeper, to investigate and to form connections, because it is not didactic. Marinescu uses art to break up various themes. He unites the forces of architecture, fine arts, film and literature to create a multi-layered overall picture, on the one hand out of a deeply personal concern, on the other hand for reasons of enlightenment.

What I learned from Daniel Kalder is to not trust any politician who writes his autobiography at the age of 30 or plans visionary monuments. What I was able to discover from Horia Marinescu was how to edit the story with many different tools to understand the whole dimension of madness.

POSTED BY

Denise Parizek

Denise is art historian and curator. She directs Schleifmuehlgasse 12-14 in Vienna, where for over 5 years she has been curating international projects....

12-14.org

Comments are closed here.