Last year’s pandemic context seems to have made no difference for Electroputere Gallery’s AiR summer programme and, as is customary for Craiova’s contemporary art space, this year saw a number of shows dedicated to the works developed during the artists’ residency there. Among them, the first project to receive the attention of a solo exhibition was Lucian Bran’s From Centuries Ago to Eons to Come – a photographic series focusing on the Ada Kaleh island and its notorious recent history .

We first managed to catch a glimpse of the work in the D Platform Season 2 group show at Victoria Art Center, in 2017, curated by Raluca Oancea. A dedicated venue, however, was long overdue for an artistic endeavour which, in its treatment of Ada Kaleh’s story, perfectly embodies such qualities defined by Thomas Weski as “artistic and documentary,” “historically present,” and “a precise description of the object.”[1] Indeed, similar to the island’s own blurred geo-political (border)lines throughout the years, Lucian Bran’s project sits at a crossroads itself. Namely, it documents traces of an absurd population displacement plan and the collective memory left in its aftermath, while simultaneously using landscape made absent to question man’s hold on land and what it means to dwell on it when faced with the enormity of time and with fate’s fickle finger.

Rigorously recounting the islet’s history is both beyond this text’s scope and redundant, given the abundance of source material available today. But suffice to say it had a tumultuous past throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, repeatedly exchanging hands between the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian one. The dispute between the two resolved when it became a Turkish exclave, only for it to be given in the end to Romania in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. When it was finally submerged in 1970 during the construction of the Iron Gate dam, it came as a shock to its (predominantly Turkish) population, who otherwise proved to be extremely resilient up until that point.

All that being said, going forward I should probably also disclose that Ada Kaleh serves for the artist a role more in tune with an absent character than of a landscape. (Of course, landscape is not just another term for the surrounding environment but also for something that is defined through social use, for landscape is always culturally determined per se, ever linked to civilisation and formed by human hand and interactions.) After all, not only is the memory of this small strip of land still vivid in the population surrounding the Danube and beyond (its Google Maps marker a testament to this), but by way of speculative documentary process the artist managed to cast doubt on its supposed geophysical disappearance too.

An evocative example of this approach, which in many regards also stands at the basis of the project, could be found in the silver gelatin prints located on the right-hand corner upon entering the gallery. Bran’s study of Danube deposits uses the camera to follow the movement of the river’s sediment downstream, across four weeks and in four locales – Sucidava, Corabia, Calafat harbour, Calafat beach. The distance covered by the deposits, i.e. 57 metres per week, was accounted for by taking a photograph each week and moving the camera from its initial shooting spot accordingly. Considering the two lightboxes also present in the show, holding film developed with water from the Danube, we might get an idea of where all this sediment is headed. Impressive in thickness, with a slanted surface and usually put on the floor (to convey one’s gaze on bodies of flowing water), the two represent strategic pins forming an imaginary course. One of the ligthboxes is a photo of Ada Kaleh’s former location, while the other shows the newly forming K Island, located in Musura Bay at the mouths of the Sulina and Chilia river branches. It would seem what was lost in 1969 (from a single spot on the Danube) has found its way not only through the rest of the river’s flux downstream, bordering four countries (Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine), but also into a new strip of land located just smack on the border between Romania and Ukraine, defying state imposed land delimitations and ownership yet again.

In his research, the artist likewise visited Șimian – the island where authorities planned to architecturally rebuild Ada Kaleh and move its displaced populace. Needless to say, the regime’s ambitions didn’t work out exactly as planned. The project was soon cancelled when said populace decided to move in neighbouring cities and Dobrogea instead, if not even Turkey. Bran treated this migration process and collective memory (along with its trauma) in a number of works. Beside the portrait of a displaced Turkish shopkeeper (Mr. Engur) taken in 2019, probably the most suggestive of them are the two photographs of the rebuilt citadel on Șimian, displayed in black frames with subtle laser drawings applied to their protective glass. Both drawings were derived from actual photos taken on Ada Kaleh, using minimalistic silhouettes to represent the different idealised perspectives which authorities and former population projected (and still do so) on the island. One superimposes what seems to be a perfect family image (not unlike Ikea stock photos) thereby raising issues of nostalgia vs. reality, while the other overlays an Ada Kaleh landmark building over the rebuilt citadel, thus being a sore reminder of unrealistic institutional expectations.

With that in mind, if Homi K. Bhabha in his essay “Beyond Photography” described Taryn Symon’s work as a “continual looping of the past-in-present,”[2] it would appear Lucian Bran’s artistic research goes further and fluidly oscillates between past-present-future. Nowhere is this more discernible than in his Reverse Archaeology […] series with three PET 3D printed vases submerged and recovered from the Black Sea – one Dacian, one Turkish, and one Greek. In creating them with present means, overlaying a patina of antiquity and presenting them as archaeological discoveries, the artist accurately emits projections of future (civilisation) histories.

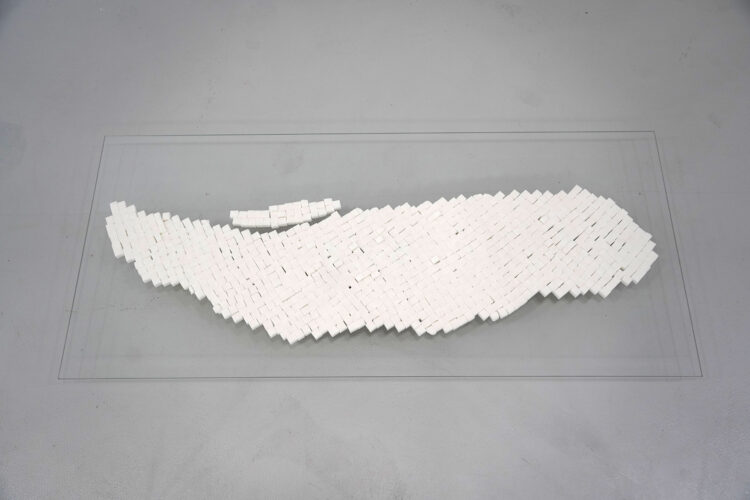

Elsewhere on the gallery floor sits a minimal installation made using cubic sugar, glass and a brick found on Șimian Island – Soluble Model of Ada Kaleh Island. It evokes not only the essence of this particular series, but indeed (talking with the artist) the basis of most of Lucian Bran’s practice up to this point. If, for example, photographic work such as Meghann Riepenhoff’s is known for drawing attention to nature’s (and landscape’s) axiomatic state of impermanence, then perhaps what Bran reveals is far more relevant and ironic given the age of the late Anthropocene and its/our impending doom – climate change. Specifically, it draws attention to humanity’s impermanent hold and control on land, sea, and any other force of nature really, even more so when confronting time itself.

Not only that, but it becomes clear how From Centuries Ago to Eons to Come poignantly embodies Fernand Braudel’s “longue durée” view of history, drawing attention upon the intertwining and causality between three temporalities – the geological one, the (socio-economic-) cultural one, and the surface-level event one (political and individual, conflict-ridden). In its representation of longue durée the project serves as a testament to man’s propensity for carefully laid plans and hope as well as to their futility, and as much a proof of our destructive power as of nature’s irrefutable capabilities to find its course.

From Centuries Ago to Eons to Come, Lucian Bran’s solo art show took place at ElectroPutere Gallery in Craiova, during 24 April – 23 May 2021.

[1] Heinz Liesbrook, Thomas Weski, How You Look At It: Photographs of the 20th Century, Distributed Art Publishers, 2000.

[2] Homi Bhabha, Geoffrey Batchen, Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I – XVIII, Gagosian / Rizzoli, 2012.

POSTED BY

Andrei Mateescu

Andrei Mateescu is an artist working with photography and an alumni of the Bucharest National University of Arts, holding a BFA and MFA after studying in the frame of the Photography and Dynamic Image...

andreimateescu.ro/

Comments are closed here.