A dialog between Diana Marincu and Marius Bercea, occasioned by the exhibition “This Side of Paradise / Dincoace de paradis”, at the Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara, May 31st-August 17th, 2024. In this exhibition, the visual experience is driven mainly by the permanent dialogue between the large-scale paintings and the small cut-out moments of rapid observations that punctuate the display like a needle and thread, sewing together Bercea’s micro and the macro universes. The personal creative process is being revealed by means of two types of archives on display: there is the analogue, pre-internet studio work, featuring drawings, psychedelic watercolours, stencils, and dioramas; and there is the digital archive, corresponding to the internet age, influenced by the devices we use as extensions of our hands, including a series of on-the-road photos in the desert. The desert remains a terminus point, a proof of nature’s resilience and a geometrical abstraction, a reminder of the “nostalgia of belonging”, a significant structural element in Marius Bercea’s work.

Hi Marius, I’d like to start our conversation with your return to Cluj, in 2013, from your “initiation” trip to the west coast of the United States. Your paintings took the form of a series of impulses and sources of inspiration that proved to be extremely fertile for what would follow. The “Transylfornian” landscape reconciled both the geography and biography. Your incursion into the desert overlayed with a fascinating genealogical inquest, starting with the gold rush that drew in massive numbers of immigrants to California between 1849 and 1859. Tell me a bit about your activity there, how you retraced the stories you heard from your grandfather, and the conceptual journal, starting from the 1960s painting of those “California dreamers” gathered around Walter Hopps’s Ferus Gallery, considered to be America’s answer to Harald Szeemann.

That’s exactly right. I already had things accumulating, impulses that started to materialize, kind of like a motif, following the on-site research, in the Californian urban and rural spaces, going all the way back to 2013. The first new works emerged from a kind of “utopian” landscape informed by two important symbols: Transylvania and California. The medium was the traditional oil on canvas.

Looking back now, I’m sure that my age, being just over 30 years old when I started this visual research, afforded me the energy and appropriate “mindlessness” to take on the adventure. I remember Henry Miller said that freedom is the strict inner precision of a Swiss watch combined with complete recklessness. I practiced avant de partir, a cultural, social, political cartography of these layers between the two spaces. There is an affective-rational order and a sequence of events in the project. From the personal side, there were the discussions with my grandpa from the Apuseni area, in which I learned about his relatives who went to America in search of gold, and those photographs, letters, and sights from California stuck with me throughout my childhood. Thinking back, I believe some came back from California after the post-World War I agrarian reform, while others built American identities for themselves and became free citizens there.

Another thing that attracted me was the San Francisco Bay painting, which, historically at least, taught me what a different style of painting can offer, as opposed to the abstract expressionism of the east coast. In my work, I find it much easier to associate this style with European research in painting, the naturalism, the attempt to understand the immediate surroundings: the color, the caprices of the air, a classic composition, inner landscape, outer landscape, etc. From my own perspective, I felt closer to the French school of painting, but also to the methodology and curriculum of the Russian Academy from the ‘50s and ‘60s (in San Francisco), as well as a visual influence from the geometric and lyrical abstractionism of the late ‘60s. I’m thinking particularly of Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Paul Wonner, Elmer Bischoff. I suppose the cultural immigration after the end of World War II, the Russian and Ukrainian communities in northern California, had an impact on the Bay Area school of painting. Victor Arnautoff was a famous and well-respected professor there.

I was also fortunate to have a close group that helped get me read up, educated, and versed in the LA artistic ecosystem: starting with “the cool school” boys (Walter Hopps, Ed Kienholz, Ed Ruscha, Ed Moses, John Baldessari), Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley, Ken Price, Lynn Fawkes, Chris Burden, Lari Pittman, Candice Lin, Rashid Johnson, Sterling Ruby, Tala Madani, etc., toward a very youthful dynamic and energy.

I think what we’ve seen in your paintings from the last 15 years is a movement from a search for space – both geographic and mental – to a search for a human typology with which to fill that space. Your research in the United States focused on architecture and design, but also literature as a kind of trusty guide.

The familiar presence of a kind of Austrian modernism in southern California’s urban development was another interesting supplement: the influence of the Viennese, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, Rudolph Schindler, the defining and materialization of the “Architecture of the Sun,” the establishment of an urbanizing system, a kind of icon of modernism in California, not unlike that of Vienna, Salzburg, or Linz, and their extension into Transylvanian cities.

Another theme that stuck with me was the abandoned city, something I’d also explored in the past. I was looking for a portrait of depopulated urbanity, a ghost town. Following the “the very fast industrialization,” or the period of intensive gold mining, the deserts of California, Nevada, and Arizona became a Siberia of the west. These sites were then colonized at the end of the ‘60s by marginal communities of the society, “itinerant” groups. Places like Barker Ranch, a former mining depo, became the residence of the Manson Family. Put another way, I uncovered an archaic lifestyle in sunny California, a vicious society of rubber tires and consumer culture, overlayed with beatnik, vagabond literature, spiritual exploration, inhibition, and social expectations.

The groundwork was initially provided by several books: Ilf and Petrov’s One-Storied America; Jean Baudrillard’s America; Kafka’s America; Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums, Big Sur, On the Road, The Town and the City; John Fante with Wait Until Spring, Bandini, Ask the Dust, Dreams from Bunker Hill, The Road to Los Angeles; Charles Bukowski, and others. Los Angeles is intimidating, where the automobile becomes an extension of the body, where understanding cultural mechanisms, the interactions of artistic practices (art, music, cinematography, architecture, ceramics, land art, screenwriting, etc.), in a space that is vast geographically but also culturally and ethnically, requires constant and sincere revisitation.

The new painting, made especially for the exhibition, Bertoia and Poussin, is a special piece. The image is problematized in multiple ways, from representation in painting to the screen to the stage, and, perhaps, we’re all witnesses, actors, prisoners.

Bertoia and Poussin communicates from between the themes of the exhibition, between the human and non-human, to intentionally establish a script, something I’ve been working with often recently. There’s an important connection in art history with this script, following the metaphor, “rehearsal for a better world”. The decision to create a dialogue between modernist hospitality, the myth, and the violence from Massacre of the Innocents comes to represent a kind of reality show we participate in on a daily basis. The element of the wall panel in the back suggests an entrance or exit but keeps out the winds of change. The peacock-feather curtains with Hera’s eye also suggest surveillance and Big Brother. In terms of the method, the painting vacillates between the intentional and the accidental, eventually forming a temporal arc.

I think what I find most captivating about the ‘60s and early ‘70s is what Peter Weibel discusses in The Allusive Eye. Illusion, Anti-Illusion, Allusion. He describes a paradigm shift in the art of the 20th century, from illusion to anti-illusion, not unlike other opposing pairs: figurative – abstract, material – spiritual. The calls have been growing for illusion to return to art, and perhaps we need it, but in your work the borders between illusion, anti-illusion, disillusion, seem to disintegrate, and the space is always being negotiated in a world that may be plastic or may be “the best world available”. You work with our illusions; you cannot work without them. As a result of these ongoing negotiations, your entire painting laboratory becomes an endless field of exploration, where the “archive” and the “accident” overlay.

The idea of lab work involves a systematization and analysis of written or visual information, but the current informational flow is dynamic, pulsating constantly. The painted environment, the historic immensity of the painting archive, prove that painting is a medium with endless possibilities.

I was interested in the mechanism by which memories are compiled. The juxtapositions of layers of memory building a reality. There’s a reason there are no road signs. Recreating the details of a memory can destroy the memory. The feeling of nostalgia or “the happiness of being sad,” as Victor Hugo calls it, is a feeling I get often. The same is true of the feeling of time becoming material and of an uncertain future. The physical distance and the American experience gave me this panoramic view on the mirage of transition. So, thematically, I choose to stick with ideas that simply pop up, precisely for the reason that they stay fresher for a longer period of time.

The cloud of inspiration is a kind of ethereal institution that quickly passes over. My studio work operates like a dual mechanism. There are aspects I visually study down to the most minute detail, which are then remade and reproduced. At the same time, there are moments of spontaneity, hazard, and “the accidental” that frame an order to thought, movement, a trip with no destination, a blank map.

Your more recent works fall back on the human figure, on a desire to understand discontinuities and transformations of a generation that came of age before our eyes. Can paintings such as The Grace of April Light or Perfume of Candor be something other than a script you’ve created for your subjects, withdrawn and alone in themselves?

The figures that appear in recent works, starting with 2019, have a personal story. Even the timing of the works is symbolic – 30 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The figures are young artists, the first generation to be born and raised during the Romanian Transition – now around 30 years old – for whom nostalgia, progressiveness, and neoliberalism formed a kind of rollercoaster ride.

The Alien Who Wanted Pajamas as a Keepsake, by Matei Vișniec, aptly addresses this social portrait: “[…] parents that went abroad to work often entrusted their children to grandparents, other relatives, neighbors […] We’ll never be able to evaluate – we don’t have the psychological or sociological tools – the frustration of these kids who grew up without their moms and dads around, who didn’t get that important time to develop the emotions and pride in life that they can only get from their parents.”

The alien with 3 eyes, 3 hands, and 3 legs comes to help the children. One hand points to the past, one to the present, and the third to the future. The blue eye sees space, the green sees time, and the orange eye dreams.

Thieves of Time, The Far Sound of Cities, and The Echo of a Breaking String are three exhibitions that feature these characters, suspended in an exhausting and difficult period of waiting. Their setting is labyrinthine and domestic, their clothing is opulent, “all dressed up and nowhere to go”. The atmosphere is feverish, tension hangs in the air, social realities are obscured, the characters seem captured in a dialogue with their own thoughts, a meditation on isolation. In the second room of the exhibition, with the Huntington Gardens paintings, Perfume of Candor, Untitled (Mirror, present tense), and others, there is a shaping of this atmosphere or the Eastern paradigm, of the painful divide between the progressive, neoliberal ideals of the parents that work in the west and the nostalgia of the recent past, the burden of the grandparents living in Romania.

The dress code is polychromatic, animal and vegetable prints that bring the fable back into discussion as a literary form, a short allegorical story, whereby the irony of human typology, morality, and jokes are personified, following a nostalgic thread of the “lizards”, of the jokes and stories with double meaning that we used to practice in the ‘80s.

At the same time, a series of applied readings join these characters: Milan Kundera, Life Is Elsewhere, Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic, Svetlana Alexievich, Secondhand Times, A. P. Chekov, The Cherry Orchard.

I’d also like to talk about the desert. There’s something interesting there that exceeds the esthetic. In a book dedicated to the desert as a literary and philosophical motif in modernity, I found a range of interpretations: the desert as a symbol of the wilderness, bleakness, as a delicate ecosystem, as a stalwart of natural resilience, as a geographic extremity, even in the sense of alterity, or as a metaphor for the unseen, as a backdrop for human intervention, even artistic intervention, as a rhetorical, literary, semiotic construction, as a philosophical topology. The author, Professor Aidan Tynan, also notices the way the desert challenges our conceptions about “place” and “belonging”. I know that you’ve discussed the special relationship of light and shadow in the desert, the lack of reference points for understanding the scale, proportion, geometry, and transforming it into a mental space, a space of thought in the visual, symbolic language, constantly swinging from representation to abstraction and back.

A fit of curiosity drove me to investigate that space “on site”. An initial map included San Bernardino, Yucca Valley, Morongo Valley, Joshua Tree, and Mojave. All the media, Hollywood, MTV iconography immediately fell away as the eternity and the horizon’s geometrical limitation instigate a new and harsh mechanism for interpretation – vulnerability, ecstasy, belonging, atemporality, and gridlock.

The experience of the esthetic, lyrical, anthropological, archaic, sensorial, minimalist, all fused together in the most confusing way. The image, surface, texture, cold and warm air, forms turning into light helped me visually verbalize a hybrid between Georges Seurat (the landscape from Saint-Denis) and Richard Artschwager, as a first impression.

The abstract painting from the exhibition, Fountain of Mud and Honey, is a psychedelic muddy volcano. These moments cannot be truly immortalized. Winter months spent in the desert bring new experiences. The huge temperature drop from day to night, the moment when the desert blooms, drop you in a Sci-Fi, psychedelic scene.

In Margaret Atwood’s manifesto, “Time capsule found on a dead planet”, meant to accompany the 10:10 climate change campaign, she writes about the “ages” of humanity. The fourth age is about the creation of deserts, as a metaphor for the absolution of the space of indifference rendered by the desert, a new empty spirituality, I’d say. But in the cracks of that emptiness, maybe “the third space” can appear, and maybe the desert helped you find it.

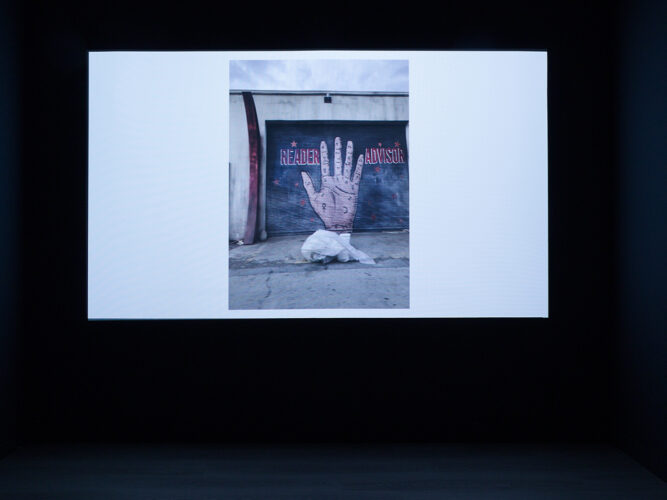

The digital video archive we’re presenting here, the “on the road” workshop, is also presented in the Sun Tan Mustang artist book, and marks the path I’d taken these ten years. There’s an aseptic relationship to the dry geometry of the horizon, whether it’s over the desert or the ocean, shore, sand, trucks, sky. There’s a vulnerability to being in that space, and you can’t read the objects or landscape at any scale. I wound up with a few thousand photographs, and they became a slideshow that drove my research forward. We start off in the morning with a kind of Piero della Francesca perspective, a single vanishing point, then midday, afternoon light, the light changes, in just half a day in the desert. In America, I also experimented with film studios, a metropolis of 8 cities, in themselves, that helped me better understand scripting and diorama, which I call 2-and-a-half-D.

Nights weren’t good for photography, but it was just as generous visually. Night trips, the constellations in perfect clarity, as if they were drawn by Vija Celmins, the cold fire of electric, neon signs, an Ed Ruscha specialty, the lonely howls of coyotes, the cold, grey/yellow geometry of the roads, sporadic rest stops, all of it feeds the feeling of belonging – a simple citizen of Earth…

POSTED BY

Diana Marincu

Diana Marincu is a curator and art critic, member of AICA and IKT, Artistic Director of Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara. Her recent exhibitions include: At the edge of the world (co-curator: C...

Comments are closed here.