Marion Baruch was born in 1929 in Timișoara, Romania. She spoke Hungarian at home, German with her nanny, and Romanian and French at school. In 1938, the short-lived Goga-Cuza far-right government passed a series of increasingly anti-Jewish laws, which gained momentum under the fascist Antonescu government starting in 1940, with one of the laws prohibiting Jews from studying at public schools. This led to Marion Baruch, who is Jewish, being enrolled by her parents in the Lycee Francais in Bucharest, where she spoke exclusively French. Her mother had divorced Marion’s father, moved to Bucharest, and remarried Sascha Roman, who, during the Bucharest pogrom of January 1941, was briefly imprisoned by the Guardists but luckily survived, while Marion and her mother were hiding at the house of friends.

Of the 1944 Allied bombing of Bucharest, she recounts:

We went to the countryside, to a community of Romanian peasants because there were bombings, and we had to hide in the cellar. I could hear the bombs falling. In this community of peasants, we ate cold polenta brought by the peasants, and we worked together in the fields. It is there that I started drawing, in that room where we had taken refuge. It seems to me that these memories with the Romanian peasants are a central point of my life.

She enrolled in the Bucharest Academy of Fine Arts in 1948:

In 1948 it was the nationalization that impressed me – “Get Out!” they said. My mother left for Israel earlier than me, I was not allowed to go with her. I did a year of art at university. There was a group of communists there who would not let the bourgeois enroll, so I was rejected the first time I tried. I managed to enter another exam , in a department where there were no communists…

In 1950 she left for Israel, to join her mother, singer and composer Daniela Dor, who had left Romania two years earlier. There she enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts, Bezalel, and studied with the Bauhaus artist Mordecai Ardon. At the age of 24, she launched her art career with a solo drawing and painting show at Micra Studio in Tel Aviv. As a result of its success, she was awarded a stipendium to study in Rome, and starting in 1954 she settled there. From 1994 to 2011 she lived in Paris, then returned to Gallarate, Italy, where she continues to live and work today.

The following interview is the result of a series of phone conversations over the course of two months at yet another peak in the lockdown of September and October 2020. The stringent COVID-19 measures in Italy over the last year, including the two months of our discussions, prohibited Marion Baruch, who is 91, from contact with her family or with outside visitors of any kind. These conversations, which were sometimes in English, but mostly in Romanian, and total more than 10 hours of recordings, created a deep bond between us. The following is a shortened version of this material, edited for clarity.

What brought you from painting to sculpture?

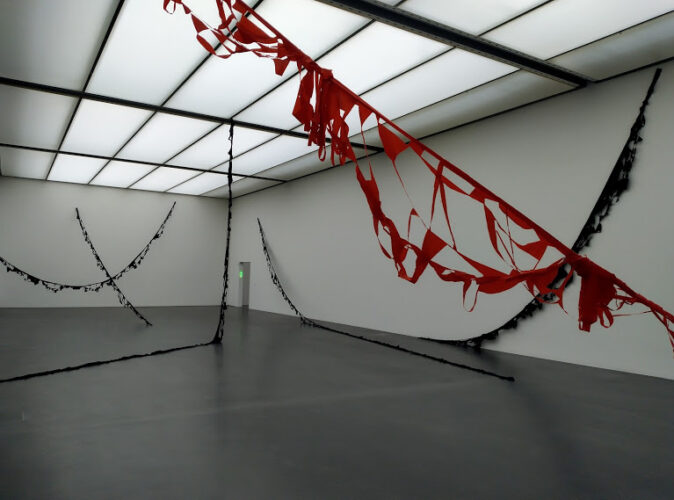

This designation, “Sculpture” (from 2011 to present), is attributed to my last project now on display at the Kunstmuseum Luzern. I called it sculpture because it was certainly not painting and… these scraps of fabric looked in space like pure sculpture.

And how did you end up working in textiles with these remnants of fabrics?

My husband had a fashion fabrics business, and he developed a new formula to create them. He did not personally make the fabric but gave it to others to produce and so the production was very rich because it could be done in a short time. I began this interest in textiles in France, in Paris. To celebrate my 80th birthday, I created a big hat out of I don’t know what material, in fact a smart Albanian artist made it for me, and I put this huge sculpture on my head, then passed it to others – it was passed from head to head.

The project she mentions, Mon Corps, où es tu ?, is a trilogy which took place at the Musee des Sciences de l’Homme and at Marion Baruch’s apartment at 32 rue Sorbier in Paris (both iterations in 2009-2010). Maybe even more than others, Mon Corps, où es tu ? clarifies Marion’s approach to the public sphere, to social interactions and artmaking, proposing the latter as collaboration between the artist, artisan, and all other participants. Her obsession with unplanned encounters, exchange, and language are all here foregrounded.

I was collecting medical boxes, empty ones, in pharmacies and in houses for old people who consume many medicines and throw away the empty boxes. I showed them in the hall of the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme in Paris. It was an installation where people could enter and follow the road, and on the floor I had thrown the empty boxes of medicine. On my head I had this strange “chapeau,” a hat which then I put on the head of other people, it was circulating. When we were walking in this material formed by empty medicine boxes, it arrived almost to the knees and produced a strange noise.

What about the empty medicine boxes was appealing to you? Why did you choose them for your work?

First it was La Chambre Vide, it was an empty room in my apartment where people could meet; there was nothing in it, one had to sit down on the floor, and anybody could enter at certain times when the program was fixed, because that was the point… to meet. They sat on the floor in the sunshine, and it was a beautiful meeting point, and there were Africans, because I was working with “sans-papiers,” immigrants, and people were coming from my neighborhood. And then I set it up with the medicine boxes. I needed a public place where to present it and to leave it and that’s how it got to La Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

And les “sans-papiers” and your relationship to homelessness – was there a common point with your own life experience?

Well, I participated in their actions, their manifestations. The police arrived and it was in February, the coldest day of the year, and they put us in a place outside – there we were so cold that we had to dance and sing, and that was the way we kept warm until in the evening the police let us go. I felt very close to those immigrants. I had never done political actions before. That was the only one in my life. It was especially important for me.

You did a lot of work including or alluding to Rembrandt.

I had seen an exhibition in Bucharest where there was a Rembrandt displayed. And that impressed me so much that it was the point where I fell in love with painting.

I would like to speak about the work La Madre, which you translated into Hungarian. You told me that the Rembrand exhibition influenced you so much.

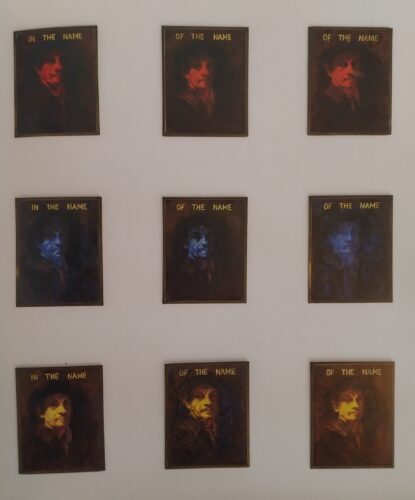

La Madre (Anyamhoz, Anymert, Anyamtol, Anyamnak, Anyamban, Anyambol), 1978-82, is a narrow wood plank that contains seven painted reproductions of a famous Rembrandt self-portrait, set equidistantly from each other. The plank was leaned vertically against the wall next to a similar composition titled The Son, 1978-82. The Rembrandt paintings on the latter are only five in number and alternate in color between red and green.

La Madre – it is formed of small paintings, 7 or 8 cm by 4 cm, let’s say, a row from top to bottom. I also titled it in Hungarian because it is my mother tongue. I declined in the title the word mother, meaning for mother, to mother, etc. And I gave this work to my son as a gift; unfortunately he died, I lost him when he was 42, it was hard… See, language was so important to me. This was a work of connection between my son and my mother.

Your maternal language is Hungarian, your nanny spoke German, you speak perfect Romanian, and English and Italian and French. Language is so important in your work. You use a variety of artistic languages in your practice. What’s the relationship between thinking in different languages and producing art in so many media…

Language is essential because the translation from one language to another is never perfectly possible. It is always something else in a way and that is a great richness. Languages for me are essential. There is an English philosopher who says that somebody who knows only one language doesn’t know his own language. I find myself in this concept. Language and translation have been central points in my life.

Tell me a little about Superart (1988-90)

This is an important work for me. The person I worked with was a carpenter and he stole this cart from the supermarket. We were together in Milan because I wanted to do this work and I needed this cart, which had to be stolen. And he made what is inside, that metal shape, which is inside this supermarket cart, and which had sloping angle outwards, and he had to follow exactly this shape and he managed to do it; the height is of a normal person, like me for example, and it is inclined towards the one pushing the cart, so the head can’t be seen. When I was holding this supermarket cart with what was inside and pushing it, I could not see anything, I could see only what was in the cart, the form that follows the cart’s shape precisely.

The work Superart was made while you started working under the brand “Name Diffusion.” It was a time when you were interested in working in a more commercial field, to discuss production and commerce in art. It is the period when the phenomenon later called Relational Aesthetics started to develop…

It was a title I came up with the gallery owner Lucian (Luciano Inga-Pin), who is no longer alive. I only put Name because I didn’t have a name. I hadn’t exhibited in important places until then, and I wanted to call myself “Name” because you still have to have a name, don’t you, and the gallery wanted to put Name Diffusion, and he was for…

For art distribution and dissemination…

Exactly, and that’s how it became “Name Diffusion.” I went to a great gallery owner and showed him a work and he told me to put it on the wall behind his desk, to see how the public reacts, and after two weeks he called me and said that he was taking it to Art Basel, the most important art fair; and then I created Superart and no one looked at what I took to the gallery because Superart was much more impressive. Maybe it was a mistake, I didn’t have patience to wait for results little by little. I immediately had another idea and that was a mistake because the public threw themselves immediately on the latest product which they thought impressive.

Under the “Name Diffusion” brand established in 1990, Marion Baruch worked in collaboration with many entities, artists, and groups, thus undermining the concept of authorship and the uniqueness of artistic objects, emphasizing instead collective production and the importance of each contributor to the whole. Through the projects undertaken with “Name Diffusion,” Marion articulated her artistic position in relation to public space and between herself and the other. She stopped working under “Name Diffusion” in 2010, from which point she resumed signing her works with her own name. La Chambre Vide and Mon Corps, où es-tu ? are some of the last projects signed as “Name Diffusion” besides her own name.

What role does the void play in your work?

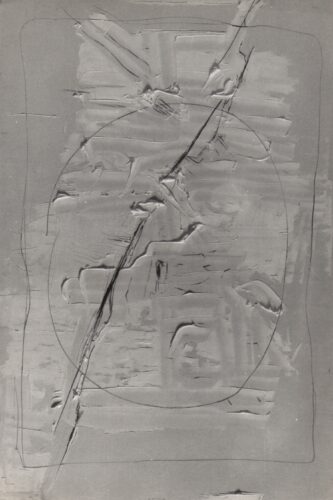

It’s so hard to put into words everything you feel inside! I made a monitor that was also from the Superart period but a little before it. And it was a beautiful work. And there the void was so important. That is, there was a frame and inside was glass and there were different frames of different shapes and in the frames it was empty; there was glass that was in the frame that was made of a very beautiful material, and I called the work Monitor (1985-1989). It became several works and that’s what I actually took to that gallery owner who put it on the wall. On the floor was this box, rusted, beautiful, and mysterious. That box was important to me, I didn’t know why. It was empty. It’s really hard to say what this void means to me.

Is it something autobiographical, metaphysical, existential, emotional?

Rather metaphysical. Like what is basically full, that is, the full and the empty come together in a way, but it is difficult to explain what we feel inside, in ourselves, in our mind. It’s like a self-portrait.

And this contradiction is present in the title of the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Luzern, Innenausseninnen that you yourself gave.

Yes, exactly, this continuous relationship between inside and outside and inside, an oscillation between extremes…

Do you see this as an autobiographical representation?

An artist is always, one can say, autobiographical in her works, but actually it is more of an essence that comes out of you in your work. It is something existential.

For example the work from the 1970s with the newspapers (Untitled), where you erase some words, and others you leave visible, this game that is a reference to Innenausseninnen, empty and full, inside and outside, this permanent preoccupation of yours with what is present and what is absent. Were you also influenced by Dada?

Dada was important. I never knew what influenced me, what grew inside me, I don’t know. Who we are, why we are like that… But Dada is still actively present in my mind. It is difficult to separate what I am from what is around me.

You were preoccupied by the “name of the artist,” the idea of brand, fame, of course themes inherent in the project “Name Diffusion”, but which can be first identified in the work In the Name of the Name of the Name (1978-1982), paintings of Rembrandt that differ from each other only in color. This repetition until the end, which is also valid for the artist who copies and repeats himself when he reaches a certain fame. But I also see in this work the zeitgeist of the period when multiples were fashionable…

Actually, these were the years when painting was just not done because art was conceptual… And I decided to paint at that very moment when painting was excluded, because art was supposed to be intellectual. That is when I needed to paint. I started this work in London when I lived there for a year.

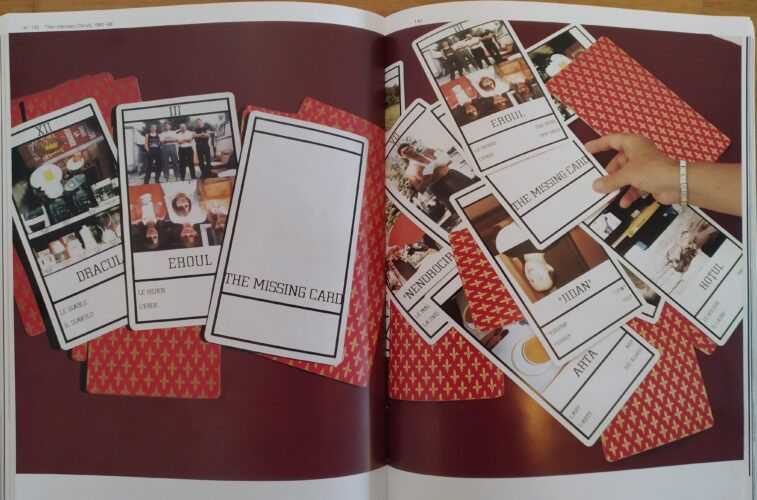

You did a piece with playing cards, Displacement for…, 1997-98. It intrigued me.

This is a work that I loved very much. In Milan I met a group of Roma people with whom I spoke Romanian, and I created this game with them. I met their families, and we went to the restaurant together and we talked about everything, because I worked a lot with Romanian migrants. Romanian emigration was in full force when the doors opened after the Revolution of 1989 and the Roma who wanted to earn money came to Italy because in Romania it was not possible.

The cards have words printed on them, such as “devil, hero, kike, thief, misfortune”, translated in four languages, and some of the words are written in quotation marks. For example, kike is written in quotation marks, as well as misfortune. Why?

These were the words of the Roma people; they said those words.

Have you ever discussed this degrading term they used for Jews?

This term was not an offensive term for them, that was the term they used, even though they knew it was an ugly term. On these Tarot cards I used photos made by my girlfriend, as well as autobiographical photos. The game was also online during an exhibition at the Shedhalle in Zurich.

You left Romania in 1950.

Yes. As we discussed in the beginning, I was 23 years old when I had my first exhibition in Tel Aviv, and thanks to it I received a scholarship to go and study in Europe. At that moment I chose something that I regret even today – I chose Italy instead of England.

Why did you regret the decision to go to Rome?

Because Rome was the past, I was thinking of Giotto… In Rome I was walking around in Piazza Navona – someone who comes from Israel and Romania dreams of these places. I thought I would end up in England anyway… Well, life’s mistakes… I should have been more serious and asked to go to England, where people look towards tomorrow, not think about yesterday.

POSTED BY

Olga Ștefan

Olga Ștefan is a curator, researcher, arts journalist, and documentary filmmaker. In 2016 she founded the transnational platform for Holocaust Remembrance through Art and Media, The Future of Memory,...

www.olgaistefan.wordpress.com.

1 Comment

Superartistic!!! Loved the interview and the evasive answers of the interviewee…she is such an interesting character with a fascinating life and quite an original view of art!