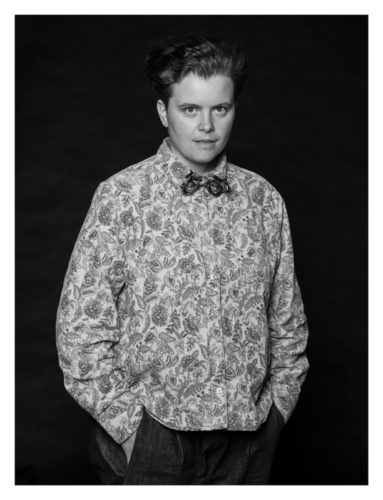

Alex Bodea is one of the most curious and incisive artists I’ve ever had the chance to meet. The acuity of her observation fuses with a conscientious critique and, at the same time, a questioning of reality that she assiduously probes. The visual medium with which she operates is drawing, materializing an approach and a very personal language for the process of exploration, discovery and understanding of the world which she inhabits. One could say Alex Bodea is a hacker of our everyday, our habits, looking for new perspectives and understandings where others have “exhausted the discussion” after reaching a predictable and amorphous conclusion. Her consciousness, doubled by an authentic experience which feels the lively pulse of proximity, outlines a particular approach in the landscape of Romanian contemporary art. As an extension of her own approach, Alex has recently inaugurated The Fact Finder, an art space in Berlin, where she has been living for a few years now. Curious about her evolution, I invited her to a discussion about her artistic training, how she coagulated her visual and conceptual exploration over time, what she looks for in the observation and processuality of art, and what is the gain of The Fact Finder.

Tell me about your artistic approach, how you came to this approach, and how did you switch from an academic training to the visual language you are currently using.

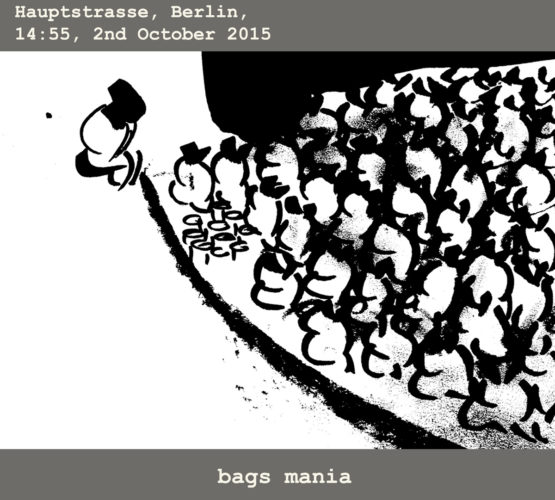

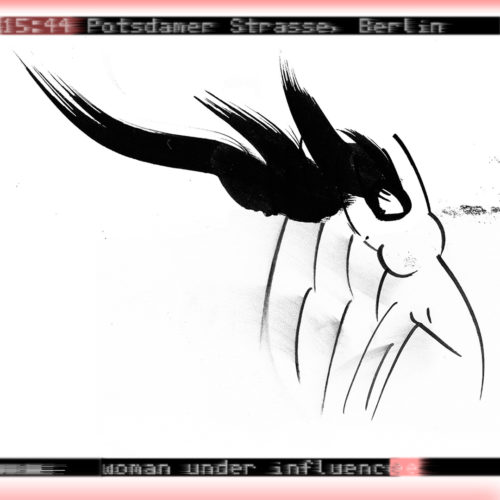

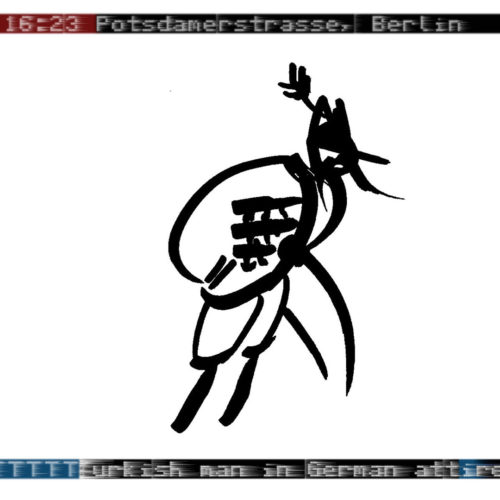

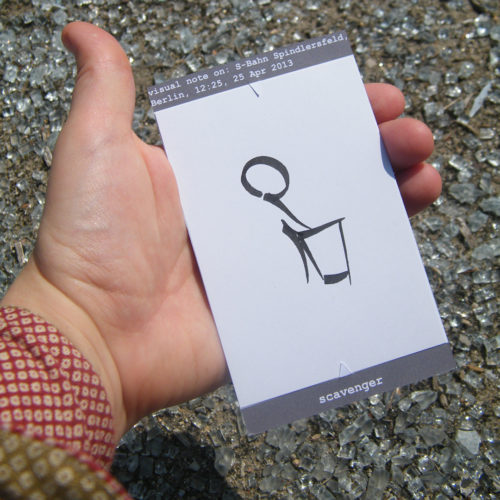

The inception point of this process can be traced to a moment of adolescence. It was then when I somehow arrived to the conclusion that there is no reconciliation or collaboration between the visual and the verbal and that I have to choose only one of the two. Up to that point, I was equally interested in poetry and drawing, but I felt like two different people each time I practiced (one at a time, never together). I perceived the drawing placed beside the word as a downgrade to the role of an illustration, a mere background aid (of course, I used to embraced a hierarchical system established by others). Conversely, I considered a text introduced in a drawing just an easy, vulgar even, solution to clarify things. And because I read somewhere that “the image is more powerful than the word” (as music is said to be more powerful than any other medium) I decided to “remain” within the visual. It took me a while to reconsider everything. But when it happened, it was very sudden. I was in my last year at the University of Art and Design in Cluj, I was interested in figurative painting, when I happened to be spending 7 hours in an airport in Baku. A few days prior, someone had given me a notebook and a pen that I happen to have on me and, to pass the time, I designed a game in which, for every word that popped into my head, I would draw something. Until departure, I already filled up the notebook. I was very impressed of how naturally this process came to me, how well this game of finding a key image for a word (and vice versa) fits me. “To name” and “to show”. Even when I was exclusively painting, I had a tendency towards synthesis, simplification, reducing everything to “a word” – approaches that were less explored in Cluj at that time. When I made a brush stroke I wanted it to remain as is, unchanged. But it so happens that painting requires addition, neither “freezing” nor subtraction (except the scracciato technique, the only one that has managed to please me, which leaves traces onto a background, similar to a kind of drawing, now that I think of it). I was frustrated with the fact that the painting I was working was all there, in the first couple of gestures; after that, all I was doing was covering up something I had already completed. Thus, after my experience with Baku, I haven’t looked back. It was all a matter of finding my instrument. I gave my colleagues all of my oil colors and I switched to gouache on paper, which I mix with gesso to make it thick, matte and as flat as possible. Over this background I draw with the brush. In terms of subject matter, I switched from the realistic-photographic documentation which almost everyone practiced at school to working exclusively from my imagination. Just like at the Baku airport, I first had the word for which I was trying to create a visual reality. I kept notes of everything that was going through my mind, and whenever I came to a conclusion, I crossed it off the list, just like in an office space. I made hundreds of gouaches over a couple of months, many of them playful, absurd, dada: “Half a mustache” “Mongol at the door of a church” “The dream of a fox in blue” “The fashion slave”. Towards the end of the gouache series, I had reduced everything to a black or white background, over which I was tracing pure lines with a brush or chalk. Soon after, I was in a bookstore where I found an album by Keith Haring. I was amazed to see how he made his designs to resemble writing, and felt like I just found my family (uncle in America). From there on, I simplified even more, almost to calligraphy (switching from brush to pen and calligraphic markers), which allowed me to work on my own themes, devour ideas, scenes, narratives. This indoor game culminated in a Laika space installation, consisting of thousands of cut-out drawings, a diorama cornucopia called “Protective Image”. In the meantime, I noticed was how easy it is to reach a “circle route”. From then on, the work is strictly in the imagination: on the one hand, it seems liberating, on the other hand, one quickly arrives to mannerisms, habits of thought, even tics, single-string approaches. I was about to go through a new transformation, from the continuous recycling of an interior ideological luggage to an active observation, with a sharp attention to what I do not know nor have experienced yet, but which I would attempt, attention to the other, to the “larger” world out there. All of which has happened, naturally so, with me moving to another city, to the “dark Berlin” as I like to call it. A city that seems to be composed of dozens of provincial towns, just like Matroschka dolls, except that they are all of the same size. However, people and subway stations are never the same. Both fascinated me. With minimized logistics (my studio space turned, under the spell of the big city with plenty, yet hard to access resources, into a writing table) and always engaged in a journey from point a to point b, I began collecting observations of what I was seeing, which later would become drawings and texts. That’s how the “visual notes” began, which I am still working on today, an archive of the city, of the people, of the institutions in which, during the last three years, I have included other projects, such as graphic reports I sometimes make for various collaborations, on different subjects and in different contexts. These are all based on visual notes, but the ensemble is composed differently, it is built as a prose. Sometimes it becomes a blog post, other times a book, often turning into a performative lecture. Now, I am starting a new approach, in which I seek to reconsider and recontextualize the observations of these last few years in the form of a book (graphic novel), large drawings, installation, and surprise! painting, of which I often think about from the perspective of this newly accumulated experience. All this, while carrying on my daily observations. And if the opportunity arises, I would love to collaborate with someone in the theater industry, for stage design or someone doing performance who is interested in augmented reality.

What is drawing to you?

Verb, adjective, a punctuation mark. A dummy test for life. While drawing, you can explore every possibility, you can speculate and simulate. You can create a virtual reality. With a minimum risk. Drawing is for art what mathematics is for science: a fundamental structure on which one can build and test. And of course, drawing transcends art many times, we apply it every day without even realizing it. It’s a good think whenever I forget I’m drawing or working on my art, it confirms that I’m doing the right thing.

How would you describe the differences between a visual documentation and illustration? To what extent do they interfere or reject each other?

I would have liked it if you’d asked me what is the relationship between an illustrative documentation and drawing in a broader sense.

The common element of a graphic documentation and an illustration is what separates them: their relationship to the text. An illustration can not exist without the text it illustrates, but a documentation may be silent, composed exclusively of images. If both are related to a text, then what separates them is the relationship between the text and the pre-existing reality/experience. Here we should discuss the difference between writing, in general, and writing perceived as journalism. It’s a very complex matter. Obviously, the lines are not as clear as they seems at a first glance.

If I were to think about the difference between visual documentation and drawing in general, I would give the following example: let’s say there is an illustrated documentation with a boulder as subject, next to a sketch of that same boulder. What distinguishes one from the other is that the person who made the documentation went to that place to discover a boulder. The one who made the sketch went there to draw it.

Tell me a little bit about the 2017 Art Encounters experience.

We arrived in Timisoara right after the terrible storm that unfortunately caused some victims and left the city without street lighting in several areas. My first concern was to find a strategy to manage the vast material offered to me by the biennial with its multiple locations and a training program that involved a new action every hour. I knew I was going to be like a courier, so, first thing’s first, I got a bicycle. Then I negotiated my editorial headquarters, the place where I would stop between two missions, where I would put the material together and pick up news about the schedule. I got an office in the same space as the organizers, who helped me a lot and with which I had a close relationship, similar to an insider. It is a dream of mine for artists to be included in the office space (in a very broad sense, meaning any place where a, as they say, “lucrative” activity takes place), to activate in the same place as most of the inhabitants of this planet. I then had to determine how much time I am to spend in each space (leaving the possibility of improvisations and plan changes), choosing to go or no go somewhere according to my intuition, which inevitably led to a fragmentary experience. But, thanks to the bicycle’s smooth pedaling, I was under the impression that I was going through linear time that was passing by very quickly. For a week, I experienced a geographical high – the possibility of being anywhere, as long as there’s will. As far as the material is concerned, it was influenced by my initial choice of arriving about two weeks before the opening, in order to observe the work of the technicians and the internal organization that offers a show in itself. A “small” world where you can watch the world “at large”. With its interactions, hierarchies, co-operations, problems, rituals, absurdities and solutions. Technicians generally are a very generous species, despite the flaws they are known for in work culture, especially in Romania. They have an upbeat spirit, like people working on ambulances. They are the ones who finally leave their energy footprint on structures designed by others. Spending time with them, before the arrival of the artists, lead to the shaping of a sweet complicity. Thus, I witnessed how the scenography of the biennial was completed, how the works were arranged and hanged. Then came the artists, meaning a completely different relationship. Until Art Encounters, with one or two exceptions, all the illustrative documentations on art I carried out were in the area of theater. Actors, by the nature of their job, are accustomed to being watched and it is generally a pleasure to watch them, sometimes making it all too easy. With visual artists, the real challenge begins, with many of them not taking too kindly to revealing an unfinished process to the public. There was a need for diplomacy and flexibility, but I also had close relationships with artists such as Pusha Petrov, Sorin Vreme, Dan Beudean, George Crângasu. And now I ask myself, do I prefer the easy way or the hard way?

Caught in this biennial world (bubble), it would have been easy to forget the outside world, had I not seen one day, as I was leaving the Transportation Museum (one of the locations), the all too saddened figure of a woman:

A reality check on Romania’s mood.

As to the manner in which I presented what I had collected, I opted for two different experiences. For one, to showcase for the first time (I had been thinking about this a long time ago, and was waiting for the opportunity) the laboratory aspect of my work. When I’m out in the field, I expeditiously write down what I notice, and then, back in the “editorial room”, I put together the material and draw from memory, trying out multiple versions. At Timco Halls, where I was given a wall with a large metal X across, I organized some of these preliminary variations in a graph, pinning them with magnets on the metal bars. In the back, on the wall, I wrote the reason why they were rejected from the final documentation next to each drawing. I called the installation “Rejected Drafts (and Why)”. The actual documentations was presented during the preview evening with the audience in the form of a cinematic reading. I also edited the documentation as a digital album, which was presented, for the rest of the biennial, on a monitor screen.

Overall, it was a rich experience and I appreciate Diana Marincu’s courage, the curator of the biennial together with Ami Barak, to bring a practice like mine, alternative and unpredictable, to the public’s attention.

What works do you consider to be your most important projects so far and why?

I don’t know if I see things in terms of “importance” but I can say that some projects have satisfied me more than others, considering size, difficulty and diversity. Among these are “The Visual Notes of a Non-Tourist in London” in collaboration with Central Saint Martins, the two-month reportage in Porto, which included a collaboration with the Santander Foundation, the Berlin International Literary Festival documentation I did in 2016 (included as a performance in the festival) and, already mentioned, the report for Art Encounters.

How do you position yourself within the Berlin art scene? What about the Romanian art scene?

Contemporary art seems to be an effort of reconsidering and recontextualizing old forms of expression, even in new media, where the technique may be new but the approach is strongly influenced by what has been accumulated so far. From this point of view, no matter the artistic community I relate to, be it in Berlin or Romania, I am also part of this effort. On the other hand, I can say that I am a “lone wolf”, trying to do everything in my own terms, not without being communicative or very curious about the actions and peculiarities of others. A lone wolf who often visits the village. And who hopes to build a new one.

Where did you get the idea for this artist-run space – The Fact Finder? What is the connection between The Fact Finder and your art practice?

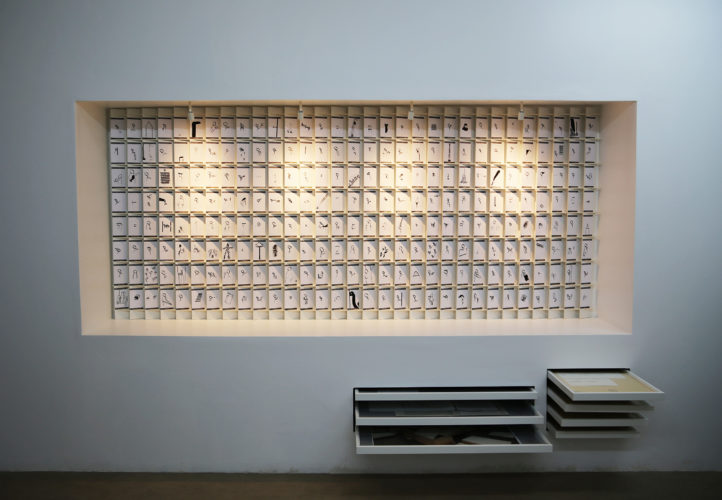

The idea comes from my own practice. I was looking for a context, a physical space in which to communicate the results of my research, a kind of “office” and meeting place. From there on there was only one step towards providing other close-knit artists with a context that would highlight their specificity. I knew what I did not want: an isolated studio to lock myself in. So I looked for a space in Berlin with a street view, not the interior of one of those Hofs. After my initial search, I did not find what I was looking for, after which I went on a trip to Italy over the summer. One day while I was there, after climbing and descending the slopes of Genoa many times, it struck me to look over the art space ads refreshed that day. I was drawn to an add for a space on Kurfürstenstraße, on the corner of Potsdamer Straße, in an active gallery area. And even though I thought it would be impossibly expensive, especially from such a distance, I decided to give them a call (without having the guarantee that someone would answer me; in Berlin there are people who are reluctant to pick up the phone, even after they list their number in a public ad). They answered the call and in a few weeks I got the space. I earned the right to pay rent (internal smile). I spent August arranging the interior to my liking. I built a wall niche with drawers for archives, to later serve as a meta-commentary of the artistic processes, presented in future exhibitions. I opened in September 2017, during Berlin Art Week, with a group exhibition where I invited new artists as well as people I had previously worked with.

How does The Fact Finder contextualize Berlin’s so very complex art scene?

The Fact Finder is one of the younger spaces in Berlin, in that it has a very precise curatorial concept, being a platform for artists who start from field research, direct experiences and values the way they communicate their discoveries. Land Survey / immersive journalism / flâneurism / archiving / travel / empathizing and narration techniques are some of the processes that we consider fact finding missions.

How do you balance your own artistic activity with coordinating this contemporary art space?

The specifics of my practice are the same as the space’s, making them go hand in hand. There are almost no boundaries between my creative work and coordinating the space; both involve fieldwork, attention, empathy, improvisation.

What kind of artists are you interested in collaborating with?

Any artist who has an excellent sense of observation and is a very good storyteller.

What exhibitions did The Fact Finder host up to now?

We had an opening exhibition with artists I had recently met and others I had worked with in other contexts (Anne Metzen / Standard Euro, Matthias Beckmann, Karine Bonneval, Alina Andrei, Sibylle Hofter), to which I also contributed; it was meant to reveal several ways of “fact finding.” Then there was an exhibition entitled “Have you seen my newest one?” (George Roşu and Theodor Schmidt), with a biographical feel and the “Bridgescratching” exhibition for the Kg Augenstern duo (Wolfgang Meyer, Christiane Prehn), which made use of audio in order to describe a sinuous cruise on the rivers of Europe.

In our latest exhibition, presented during the Gallery Weekend, we had two film projects (I’m using the word projects due to the complexity of the process and the intention of the authors to overcome the film environment using an interdisciplinary approach). One of these is “Expression of hands”, a cinematic essay by Harun Farocki detailing the presence of hands in cinema, a page in the cinematic lexicon on which he worked his entire life. One particularity of our space is to reveal in great detail the processes of a work’s conception and transformation, for which we built a special niche in the wall, with drawers and archival compartments. In the niche we had, among other things, a voluminous correspondence collection between Harun Farocki and all those who contributed to the film, notes, sketches and ideas.

The other project “Touch Me Not”, by Adina Pintilie, winner of the Golden Bear 2018 (of which we screened a fragment before the film’s release in cinemas, which will probably take place later this year) is an attempt to redefine privacy, a fiction film that has (very slightly) picked up certain documentary techniques, also redefined here. This film is the first part of a multi-platform project (film/video installation/performance/website) which can soon be followed in several art centers in Europe.

For this exhibition we had more than 300 visitors during the three days of the Gallery Weekend, which is generally a period of mass mobilization in the art world that very clearly shows how consensus is needed in order to articulate a reality: an artistic center, a school, a great artist.

For our next exhibition (which we will be doing in a different period of consensus, The 2018 Berlin Art Week), I will put together some of my cut-out installations/scenes, a game of characters that I uncovered in the city streets, titled “Un-seen people”.

What is the gain of this artist-run space and how do you imagine it in the near future?

The gain is to facilitate dialogue between artists with similar practices. I want it to become renowned as a generous context in which these practices can be carried out.

If you were to summarize your activity in one word, what would that be?

Communication.

You can watch a drawing reportage that Alex made in London as part of the Acts of Searching Closely exhibition at ASC gallery.

POSTED BY

Ada Muntean

Ada is a Graduate of University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca and has a PhD in Visual Arts (2019), conceiving a research thesis entitled "The Human Body as Image and Instrument in Contemporary Art....

Comments are closed here.