If other recent exhibitions have approached Iosif Kiraly’s work as a phenomenological architecture that uses photography to question the intimate structure of reality – time, space, memory – his last exhibition, Closed Doors. Open envelopes, opened in April 2018 at MNAC, offers a glimpse of a Iosif Kiraly who is a supporter of the constructivist game with ideal targets, with performances in nature and also part of the authentic relationships around the vast mail art network. This complex project reveals less used, hidden facets of his life and artistic practice during the communist era: a postal art collection accompanied by a collection of stamps (possible artistic identities), sketchbooks and personal notes, music reviews, official documents such the UAP permission to attend Atelier 35’s exhibitions (despite the fact that he has a degree in architecture and not the arts). Along with this playful side (focusing on either constructivism or authentic performance) the show includes a series of works from the ’90s of a strong socio-political nature, lucidly mapping the streets brought back to life with the collapse of the old regime.

It is worth mentioning that although Closed doors. Open envelopes does not directly involve what can be called as the nucleus of Iosif Kiraly’s work – see the subReal era or the renowned Reconstructions projects in its multiple and varied forms – it does offer new ways of reading his art, enriching this nucleus with new meaning.

In my opinion, the vibe of this show is based of two characteristics. First of all, it is about the desire to collaborate and open up to those who contaminate Iosif Kiraly’s life and work. One could speculate on how he was influenced by the SIGMA group, by the spirit of the Fluxus movement dedicated to live art, by Zen thought. What is important is that this show has managed to highlight collaboration as an existential trait of artist and professor Kiraly (who is part of subReal, syncretically engaged with writers, architects, anthropologists or landscape artists, surrounded by students and teaching). In this sense, I am reminded not just of the honesty with which he regards all those he worked with on performances, installations and photo projects, but also of his organic relationship with curator Ruxandra Demetrescu, the curator of this project and the exhibition that took place at Jecza gallery (Timișoara, ArtEncounters Biennale 2015), the starting point of this project.

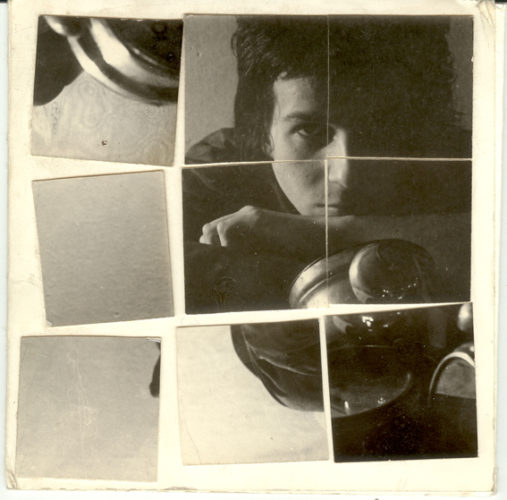

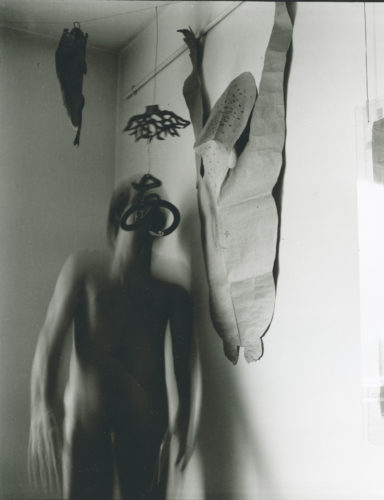

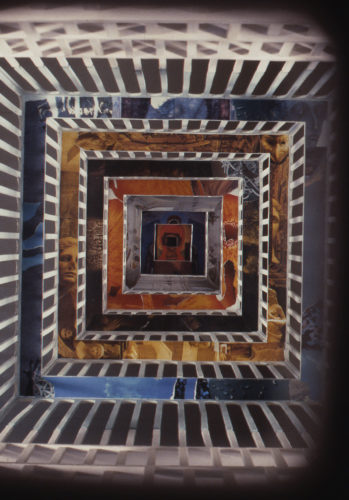

The second element of surprise would be the explosion of engaging media: from notes, sketchbooks and sketches on tracing paper, to actions, objects and photographs. Photography also comes in a large spectrum of forms: photography as an abstract game of shapes (see the reflection series, anamorphosis at an urban scale, New York, ’95), pictorial photography that questions the death of beauty and contemplation, photography as witness to an action, site specific installation-photography (the plastic organs for teaching purposes photographed in unusual contexts), photography as an expression of the street (in Romania after 1990 when the streets come alive), photography as documentation for a historical monument or political regime (Ruxandra Demetrescu mentions photography as a critical image, a concept by Didi-Huberman, the image that gazes back at you).

Next I will address a series of questions to the artist who can offer a direct recount of this complex project. I will use the object tone of a journalist, despite our close collaborative relationship:

Seeing as you used photography in such diverse ways throughout your artistic practice, would you say you developed some specific preferences? Have you developed a personal definition of photography? Would you describe yourself as an artist photographer or rather as an artist who works with photography? And seeing how you also teach, do you believe photography is something that can be learned?

As an artist, after decades of working, I’ve been through various stages and my relationship with photography was and still is dynamic, constantly changing. From a means of documenting more or less constructivist objects, personal and group actions during the ’70s and ’80s, to the basis for various interventions for mail art works (collage, stamps, sketches, painting and experimenting with different photographic solutions). I then used it as a means to subjectively document the compulsive political and social changes of the early ’90s, as well as the chronicled transition that seems to be never ending. Then came the Indirect project, which later gave birth to Reconstructions and Synapses, followed by my collaboration with architects Mariana Celac and Marius Marcu Lapădat in photographic projects about architecture: Tinseltown, Marshalling Yard or Bucharest in layers and perspectives to RO-Archive, D-Platform (which you are very familiar with since you were also involved) together with young artists and photographers, most of which were students of ours, as well as anthropologists, landscape artists, philosophers, etc.

On the other hand, in the mid ’90s I realized, along with Călin Dan within the collaborative project subREAL, the huge possibilities and challenges (from a moral, aesthetic or legislative stance) you must face when you’re an artist working with photo collections, appropriated photographs, archives and so on. That’s also when I started being interested in photography not just as a means for visual expression, but as a cultural phenomenon, as a sign language and system. This mutation could have also been influenced by my teaching career and my need to discuss with my students topics that go beyond the basic level of technique and composition. After all, this is what should separate the way in which one studies photography at practical courses as opposed to a specialized department within an art university.

Yes, photography is something you can learn. For me, one of the reasons why I founded the Photography and dynamic image department at UNArte, along with a group of friends, was that anyone who wanted to study photography wouldn’t have to aimlessly wonder for 25, like I did, in order to get to a point where you could arrive in only 5 years with the right guidance and necessary information. Another reason was contributing to creating my dream school that I would have wanted to attend after graduating high school.

I don’t mean to say that I lost those 25 years in which I gradually attained, with small successes and small failures, a certain level of mastering photograph, or that studying architecture did not prove helpful. On the contrary, I believe that in both situations I broadened my cultural and social perspectives, which was and still is extremely helpful. I also firmly believe in sinuous, detour paths that are more certain that a straight line sprint from start to finish.

Both the Bauhaus derivative that has helped me use photography combined with other techniques, as well my mail art activity in particular, where photos were edited in rather unorthodox ways, clearly make me up to be an artist working with photography instead of an artist photographer. The distinction is very subtle, yet there are nuances when it comes to the various ways of engaging with the current practice of photography.

Getting back to your current exhibition, I could gather that your students did not hesitate to assist in putting the show together and documenting it. My question is whether many youths visited the show. Is the new generation interested in art during ’70s-’90s or in recent history presented in an artistic manner? Could this non-formal educational approach to photography and art become a model for such practices on the contemporary scene?

A lot of people visited the show and it’s no wonder that the majority was young people. Despite all objective and subjective criticism towards MNAC from some of the active players in our small art scene, one thing is for sure: there is a loyal and numerous audience who visits the museum as if it were a shopping mall. I’m not sure why that is; maybe it’s because some find the place to be cool, others come for the breathtaking view on the terrace, and other just end up engaging with the many events taking place there. There are a lot of foreigners who visit the place for the first time with some even returning. Most of these people visit and re-visit the art shows as well. During these last months I was at the museum several times a week to check if everything was working accordingly and I can confirm that there were always visitors in halls. The hall custodians also told me that many youths visit the show every day.

When we were putting the exhibition together I had constant support from a group of students. Same with many other adjacent events I organized during this time (for example, the sound installation 87 Clouds Will Rain for You, which took place on the 30th of July at UNAgaleria). I believe that through these practical activities, students get a chance to come into unmediated contact with the art world and the mechanisms behind exhibitions and events, which is important. This way, they have a more nuanced perspective on artistic phenomena.

I notice something that makes me very happy regarding our current students: after a year or two of university, after coming into contact with canons from art history and photography, with names that frequently pop-up in Taschen albums or other renowned publishing houses, students yearn for something more, for something closer to their geographic area and the place they were born and raised. They want to find out more about Romania’s underground history, something that might help them set themselves apart from other youths who only get their info from said albums or steadily visiting artistic malls like TateModern, Moma or Centre Pompidou in real life, or sometimes simply online. I’ve witnessed it countless times in the last years, how students’ interest exponentially grows, how they become more interactive when I tell them about Romanian art in the ’80s and ’90s, about actions I took part in along with colleagues for photographs only or for a small gathering of friends. This did not used to happen a few generations ago. Back then, many students and young artists were enthralled with the superstars of the contemporary art market, and overcome by a provincial shame (unfortunately still present in Romanian society) that made them think that the West is where every good thing happens, whereas the East is home to all expired and worthless things. Now, most of our students are already traveling abroad from a young age, they’re communicating (in real life and also via social media) with other youths with the same preoccupations from across the world. Today’s students are more knowledgeable about life, art and „foreign” schools, allowing them to make better judgments. On the other hand, in this era of globalization, the West isn’t what it used to be…

During an interview we conducted in 2007 for the publication Photography in contemporary art, you were lamenting over the fact the Romania does not have a museum dedicated to photography, nor a photo department within the Romanian Union of artists. Did things change in these last 10 years?

Unfortunately no. There was some commotion about it and there have been public debates right after Mihai Oroveanu’s untimely death, the man who was probably the most adamant about the museum, or rather a photography center and he was willing to donate his entire collection (no doubt the biggest and most complex private photo collection in Romania), which would have been the catalyst for building a center for researching photographic images, with a program oriented towards both studying the history of photography, as well as promoting contemporary photography. Unfortunately, none of those who intended to put into practice what Mihai dreamed of did not have the influence to persuade neither the Ministry of Culture, nor the Bucharest Town Hall to fund this initiative, not to mention the inability to find a space for it all.

Seeing as you have a real interest for constantly working with photo archives (see the subReal projects dedicated to the archive of ARTA magazine and the collaboration with CNSAS, “ground zero for street photos in the communist era”) do you think that archives (vernacular, personal or institutional) constitute an important instrument for the postmodern artist? Do you think that the ongoing exhibition at MNAC could also be considered an archive?

Yes, I think it is evident that archives (or photo collection, unorganized stacks of photos) make up a material that is being increasingly used by artists. I need not look further that our own photo department at university, where each year, at least a quarter of diploma works involve, in some way or another, photos that have been appropriated from various collections. The way I see it, it might be a reaction of resistance against the proliferation of digital photography and the fact that any mobile phone user can pose as a photographer, in the sense that they can take photos that are good enough to gain some likes and hearts on social media. Those with higher photographic aspirations, especially artistic photography, but who are still too young to have coagulated their own means of expression, attempt to (technically) position themselves, whether they realize it or not, on a different level. That’s why many of them chose film photography in lieu of digital cameras or, in an even more radical manner, build their works using archives and chose to become artists working with photographs (see above the distinction between artist photographers and artists working with photography)

As for the MNAC art show, the works contained therein do not necessarily fall in the archive theme. Of course, with the passing of time, you could say that the oeuvre of any artists becomes and archive of images.

It’s evident that objects have a complex role in Closed Doors. Opened Envelopes. At first, the object is abstracted, through sketches or the object itself, so that it later transforms into a body and a pretense for photographic documentation, charged with poetic or social significance: the pig ritual or the plastic organs installation used during the communist era as learning material. As for the mail art projects, the letter-objects oscillate between experimental print and a proto-form of relational art. I’ve noticed that there are certain themes that mark the entire exhibitional route: the portrait, the mask, the alter-ego, the mannequin. The body follows a twisty path from an enveloped object, exhibited and fallen on the stairs to the anatomic mannequin with detachable organs (see Deleuze’s body without organs). In this case, I would like to know what working with the object and the body means for Iosif Kiraly?

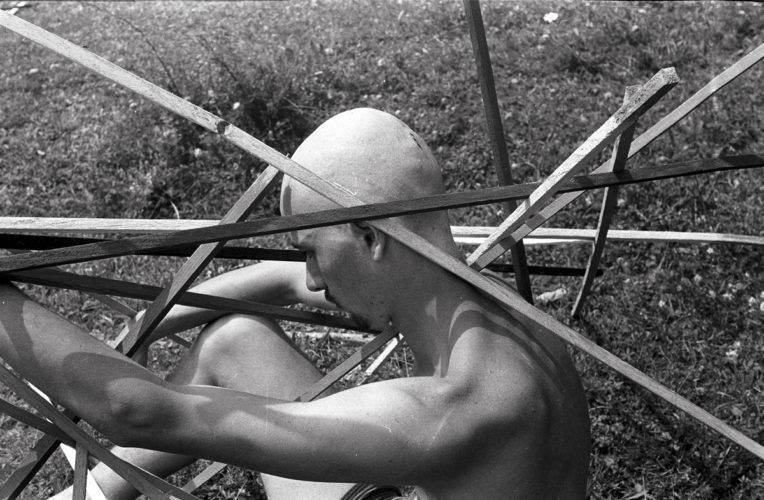

Although I love good quality conceptual art, and I know just as well as you do that there are master pieces of contemporary art that are better seen than talked about. I still think that the perfect work of art can properly balance objects and concepts. During my constructivist period, I mostly understood art from the perspective of formalism, composition, chromatics or functionality. As time passed, however, even though I continued working in a constructivist manner, I attempted to grant these shapes a symbolic, spiritual dimension. I call this phase post-constructivism. Antibabel, A dog’s research, Modular structures shaped as a cross, Mirror animals are all part of this period.

At the same time I realized the expressive power of my own body. The human body, in various forms, has been present all throughout the entirety of art history. The most intense emotions can be obtained with the help of the human body. I can’t remember the first action I ever saw where the artist used his own body. Perhaps it was in photos…

But I do know that during my junior year of high school I was doing organized practice at the art high school in Timișoara at Strungari, in the Alba district. The Tulcans were part of the organizers and the theme was Land Art. They were prepared and brought a few hundred wooden sticks of about 1 meter each, dyed in basic and complementary colors.

Some students used them for various interventions in nature. I, together with colleague Grigoraș Juravlea, did multiple variations of works in which the human body was part of a structure created in nature with those colored sticks. I remember, years after that, a certain art critic told me: I can see the Bauhaus school in this, influences by Oscar Schlemmer, etc. I was somewhat amazed because I never thought of Oscar Schlemmer. I’m not sure if I even knew of him back then, although I probably should have…

In the case of your early photo collages (see the tape, pencil or color interventions) but also in the case of some of your more recent works in which various temporal and spatial connections are marked with needle and thread, there is a certain haptic dimension. To what degree can photography become an object in the digital era? Does it make sense to take into account a possible recharge of the technical image with aura? (see bringing back the aura in Groys’ comments on Benjamin)?

Digital technology helps me tremendously in my photography work. On one hand it allows me to take a great (huge) number of photos that I use in my panoramic mosaics without worrying about used film rolls. It also allows me to work in various layers of transparency which I mold as if it were clay. I have a very tactile relationship with digital photography. I believe this is also due to the years spent doing collages and various photo interventions. On the other hand, I like to experiment, to find new visual formulas for my concepts. This is what a post-digital period looks like: returning to certain techniques and procedures that some might consider outdated (nails, wires, duct tape, etc) combined with the most digital technology possible (if you can call it that).

During the guided tours you also bring up the term vintage photography. How do you respond to this art market requirement? Is this also related to an attempt at regaining authenticity, the old status of originality?

In the case of the MNAC exhibition there was no art market requirement, but rather a curatorial decision regarding the manner in which such an exhibition that aims at history and recovery could be best produced in the context of a national museum. I talked a lot about it with Ruxandra Demetrescu, I also discussed it with other specialists, among which Carolina Levandovka, photography curator at Centre Pompidou, who confirmed that such an exhibition should exclusively make use of vintage photographs, if these are available. This, of course, despite the fact that we do have the technical and financial means to scan the original negatives and print them at a much higher quality and size.

Vintage photography is praised by both art historians and art collectors as a standard, not just for the artistic level but also for technique, and an all-around indication of the artist’s financial possibilities during the time when said photo was taken. Along with what is seen in the images, the fact that these photos were taken on ARFO, AZO or ORWO paper tells a more sincere story of that certain era than a high quality inkjet paper, be it Epson or Hahnemuhle, print could ever tell.

In my opinion, the collection of notes, letters, sketches, typewriter notes offer a certain charm: a direct look into the life and laboratory of the artist. One could say the entire route could be placed under the sign of authenticity: a very personal and brave exposure that gives the impression of an intimate diary. An exposure in which the technical image attempts to go beyond the limits drawn out by Benjamin: regaining the aura along with the honest, unflattering account of the ephemeral, the perishable. I would like to ask you two questions. To what degree do you think it’s possible to properly represent within a museum this type of live art, be it actions in nature, mail art or your personal inter-relationship set by your artistic route (this goes for other shows, like the Fluxus exhibition at MNAC from a few years back)? And secondly, I am curious if it was hard for you to decide whether to uncover your laboratory and if you’ve ever felt exposed or vulnerable?

Highlighting the artistic process rather than its end result was also a curatorial decision. The exhibition is mostly focused on presenting artistic and spiritual musing, rather that final works or solutions. In this sense, collaborating with architect duo Atelier AdHoc (George Marinescu și Maria Daria Oancea) was essential.

As for your last question, I must admit I do feel more comfortable presenting sketches or photos (even intimate ones) instead of texts from that period. Maybe it’s because the images are more ambiguous and polysemic, leaving more room for interpretations, while the texts are strictly focused on certain preoccupations or what I was reading at the time.

It is true that some texts can indeed constitute additional elements for a better understanding of what I was doing back then, however I am a bit afraid that for some viewers or lazy critics those texts might become to only key for interpreting the images, closing off other possible interpretations.

Based on what you said, that any artistic demarche needs a background, a series of models, we notice that your earlier works make up a reaction towards an entire relationship tree with your high school teachers, Doru Tulcan and the other Sigma members, and other young artists and musicians from Timișoara, like the band Trio Contraste. How would you describe this common pulse, do you think that despite the oppressive regime there was an underground communication and spirit among Romanian artists in the ‘70s and 80s? What can you remember about Timișoara’s art world (especially in the presence of the unusual group of German writers, Herta Muller, Richard Wagner, etc)?

I believe that Timișoara during the ‘60s-‘80s was the geometrical spot for numerous intellectual forces, some visible and some underground. There were all sorts of inner circles that intersected, came into touch and would more or less communicate with one another. I was gliding between the circle of mature artists, my old professors or mentors from the Sigma group or from school, to another circle of colleagues from Atelier 35 plus a group of very talented and dynamic architects who were very well informed about all the goings-on in their area. Our circle was also shared by a few musicians who made experimental contemporary music (using scores) but also had a huge appetite for improvisation and syncretic actions, thus combining multiple artistic mediums. In additions to these groups, during the mail-art period I became a part of an international organism whose pulses would translate into giving but also absorbing from me daily messages and a lot of art works.

Besides these groups which I frequented, there were also others, like the German writers you mentioned, who I haven’t had the chance to meet back then (even though I was close with other relatively known writers since before and after 1989). I did meet some members of the German writers group in the ‘90s in Berlin.

There was a very interesting experimental theater movement at the Students Hall, a cinema club and perhaps others. Before the late ‘70s (after which they spectacularly and illegally emigrated), the band Phoenix, an institution in itself, would polarize entire masses, but unfortunately I was too young to be part of it.

We’re reaching the exhibition’s hot spot, the area delimited by curator Ruxandra Demetrescu under the fit title mail art “cabinet”, where the rhythm suddenly accelerates: the viewer is overwhelmed by an avalanche of envelope objects. Here, the avant-garde meets lettrism and postmodernism, opening up multiple directions: visual poetry, stamp art, unwrapped art. This is where highly personal objects alternate (love letters to his future wife or the series of stamps which confirm the artist’s multiple personalities akin to Pessoa’s heteronyms) with letters received from various corners of the world (Kiraly’s collection contains numerous foreign works). I have quite a few questions… regarding your collections, do you have a favorite author or project? What can be said about the issue of authorship in the case of this giant archive, can we use terms like collective author or the death of the author? Then, can you tell us more about the exhibited stamps? Are they part of a game of multiple identities or a Zen game with randomness (I’m thinking of John Cage who used to distinctively, yet randomly mark his experimental prints from series like Variations III)?

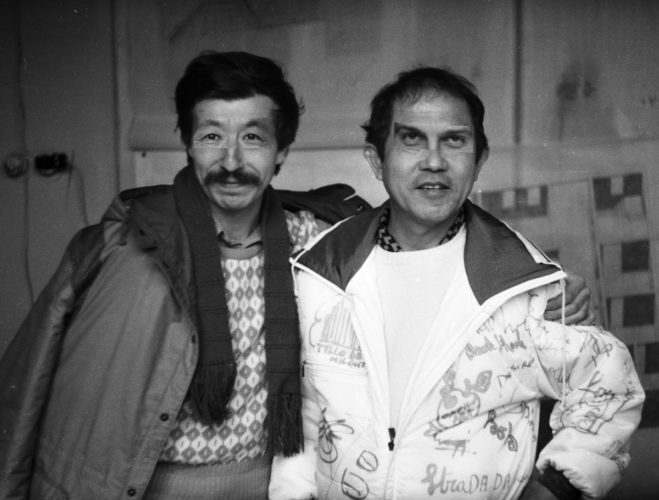

The idea of a collective author is central in mail art. One of the most interesting (and long lived) projects is called Brain Cell and it belongs to the Japanese artist Ryosuke Cohen. In his invitation to participate in the project, he wrote that a single cell has no real power, but combined together in large numbers, multiple cells can bring about wonders of nature, like the human brain for example. He would then ask each participant for a stamp, a seal or a reproducible sign.

Brain Cell was a collective project that became representative for the mail art network, where the concept and process (of creating images) was more important that the products generated by this project on periodic, weekly, monthly basis. Ryosuke Cohen acted like an artistic lung that permanently absorbed stamps, signs and symbols from around the world, after which he would mix them and send them back to where they came from. He would breathe in individual images and breathe out collective images.

Another project I took part in, in the registry of the collective author, was a performance by Shozo Shimamoto (1928-2013) at the Centre Pompidou in 1986, during a huge exhibition on Japanese avant-garde. Shimamoto, member of the GUTAI group back in the ‘50s, was one of the most active mail artists in the ‘80s. Over more than 10 years, he developed a long series of actions which transformed his own cranial crown into a support for his art. The show at MNAC exhibits a few photos from that action along the invitation I received back then to send to Centre Pompidou a word that would be written on the artist’s head during the performance. I remember I had just finished reading a volume of short stories by Borges and I was fascinated by one in which the main characters accidentally discovers a point in space (Aleph) where all points in the Universe are visible. I mailed the word Aleph; the exhibition also contains a copy of a page from the Herald Tribune with a photo of the action in which François Léotard, France’s then minister of culture, reads aloud the words written on the artist’s head. You can clearly see my word, Aleph, smack in the center of Shimamoto’s head.

In 1895, a year prior to the performance at Centre Pompidou, Shozo Shimamoto paid me a visit in Timișoara, during an art tour he took around Eastern Europe. During the two days he stayed with me, we had long, intense conversations which definitely changed the course of my evolution. I remember at one point I confessed to him I am sometimes displeased with the fact that I personally strive to send unique and personalized messages to each of my mail art partners and in return I often receive impersonal Xerox copies. He then told me something that intrigued me and I initially disagreed: “it doesn’t matter what you send, what matters is that you send it, to feed the network”. Mulling over this statement, I realized that for him, as well as other mail artists, the network itself is the work of art, not the singular pieces that circulate like particles within the network’s veins. Mail artists were a kind of bees, not stand alone organisms, but cells within an organism called hive. From this perspective, a mail art exhibition is more like an insectarium, devoid of the life or excitement you would feel when you were part of it, when you were waiting for a reply and when you opened the mail box (in the context of the ‘80s when nothing was really going on in Romania) and all sort of objects and colorful envelopes fell out, bringing with them the fresh air of freedom…

Yes, the mail art network was a utopian construction and many ideas associated with postmodernism, which were later developed and analyzed, guided me while I was doing postal art. Most of the time, when you embark on a new journey, when you’re experimenting, you’re not really aware of it at the time. You simply push forward. Only with the passing of time, if your route were to consolidate and actually go places, will you realize that you might have also contributed with a word (could that word be Aleph?) to the writing of history.

Can you describe your relationship with Ruxandra Demetrescu, the curator of the exhibition? How did her interest for the artist’s condition during the communist period, for photography as a political instrument, her appetite for researching the relation between private and public space (Hanna Arendt) mix with your role in the communist regime: a creator of alternative survival spaces (in the studio or in nature) or a subjective documentarian of a never ending transitional democracy?

Ruxandra Dememtrescu is not a curator in the sense typically used in the context of contemporary art. She is a refined erudite, an excellent scholar of classical, modern and contemporary art history, capable of offering a surprising mix of ideas from various areas of expertise. She contributed to educating numerous generations of art historians in the last decades, some of which have become renowned curators themselves, in and outside Romania. Her role models, along with those already mentioned, are Aby Warburg, George Didi-Huberman to which the exhibition, along with the text, represents a form of expressing their own ideas.

Our collaboration was smooth, no bumps in the road. I’m sure we’ll work again. She offered me freedom and at the same time she contributed with unexpected perspectives in reading some of my works or artistic phases. And I like that; I appreciate the fact that what I’ve created can give birth to unusual interpretations.

CLOSED DOORS, OPEN ENVELOPES. IOSIF KIRÁLY – EARLY WORKS, 1975 – 2000

Artist: Iosif Király

Curator: Ruxandra Demetrescu

26.04.2018 – 16.09.2018

MNAC Bucharest

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.