Contemporary painting is often quoted as commercial, unoriginal, and irrelevant. Theorists have been claiming the death of painting since the establishment of Modernism, and shouts of its resuscitation have echoed since the 1980s. Though perhaps not leading the avant garde in recent decades, painting continues to carry weight in the collections of art institutions and the pages of art journals and magazines. Among the global trends of installation and new media, painting is still being made, exhibited, and collected. However, painting was notably absent from the 8th Berlin Biennale and largely missing from the most recent Documenta festival, and isn’t regularly shown at Berlin’s many project spaces and non-commercial galleries. Berlin is home to to an experimental cutting edge arts scene, and is an important international stage for the emergence of new practices. Where does painting fit into this terrain and what does Berlin’s painting scene look like?

Common criticisms of painting as a medium are generally associated with ideas of the art object as commodity and that the survival of this traditional medium in a digital age is purely market driven. The over-representation of painting at major art fairs certainly backs this up. Another criticism attacks the medium’s self-referentiality. A formalist approach in painting employs a unique visual vocabulary, where colour, composition, and technique are responsible for creating a meaningful viewing experience. Painting also has a self-referential entanglement with its own history. More so than new media works or installations, a painting, purely by being a painting, solicits an art historical lens for viewing. All works of painting are, in some way, in a dialogue with painting’s academic past. This past is one heavily tied up with national heritage and patriarchy, associations global contemporary art practices often attempt to reject with an emphasis on accessibility.

The twentieth century turned painting on its head, with stylistic movements rapidly developing to the point of an existential crisis. Answering to the minimalism and medium-specificity of High Modernism, emerging conceptual, performance, installation, and video art practices of the 60s and 70s emphasised concept, creative process, and inter-media approaches. Yet painting fought its way back onto the mainstage with a return to expressive and representational modes. For the German Neo-Expressionists, dubbed the Neue Wilden, this was part of a general shift in society towards confronting and digesting the country’s troubled recent history. By the 1980s, painted works of intense colour and bold gesture, of historical, mythical and erotic imagery and narrative, flooded the international art market. This dramatic resurgence in popularity, and the ensuing art-market boom, invited criticisms of a commercially focused practice, the kindling for which had been lit decades earlier.

The coming of a globalised digital age is often said to have spelled the end for painting’s capacity to stay relevant. After the fall of the wall and during the nineties, Berlin experienced a cultural shift; it was an era of experimentation. Still recovering from the cultural lock-downs of the Nazi era and Soviet censorship, Berlin embraced a new era marked by new modes of communication. Berlin was an important site in the development of internet based critique and early experimentation with internet-based art. Influential online critical networks like NetTime and the art-specific Rhizome both have their origins in a mid-nineties Berlin. New Media Art now dominates the cutting edge practices of the international contemporary art world, encompassing all forms of digital art, and including performance, conceptual, and installation practices. Berlin is home to a great number of galleries and project spaces dedicated to New Media Art and, accordingly, to global accessibility and cross-cultural exchange, that digital mediums easily facilitate.

Even museum culture has come to favour installation, new media, and performance. However, it seems art institutions are still the last stronghold for publically hyped, large scale painting exhibitions. In 2013, four of Berlin’s major art institutions thematically collaborated on four coinciding shows under the title “Painting Forever!” (coincidentally, also opening that year was “Painting Now” at the Tate Britain and contemporary painting survey “The Forever Now” at MoMA). The exhibitions all featured Berlin-based painters and showcased a range of positions, including the indulgent materiality of Anselm Reyle’s foil paintings and Martin Eder’s pyschosexual realism in the boy’s club line-up at The Neue Nationalgalerie. Contrastingly, the Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle grouping of four women artists was imbued with sentimentality with the title “To Paint Is To Love Again”.

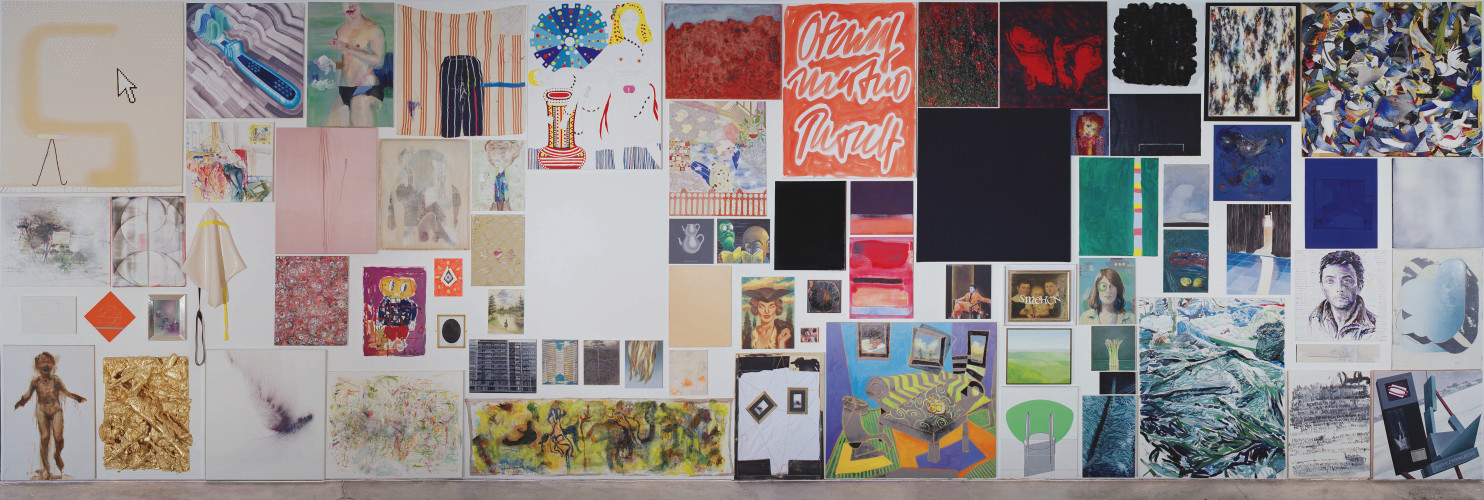

KW’s edition, “Keilrahmen”, had over 70 artists on the bill, ranging in approaches and at differing points in their careers, giving the most ambitious attempt at surveying what a current local painting scene in Berlin might look like. The tightly framed one wall ensemble included works by Frank Nitsche, Friederike Feldmann, Dorothy Iannone, Sergej Jensen, Bernhard Martin, and Andy Hope 1930. I asked “Keilrahmen” curator Ellen Blumenstein about curating and viewing art in a local context, in particular, whether it is still useful, or even possible, in a globally connected contemporary art world. Her answer emphasised the importance of the specific political, social, and cultural contexts of an institution’s location, contexts an institution’s program should reflect. The hopes for the “Painting Forever!” exhibitions were to raise questions and encourage debate about the current position of painting in contemporary art, and to demonstrate a painting scene alive and well in Berlin. While the shows were popular, criticisms proclaimed the works were mostly a reshuffling, or a reinvention at best, of recycled styles and techniques of earlier decades. This issue of originality hangs over all contemporary art making, but painting in particular has such an enormous historical and stylistic index behind it that it makes one wonder if originality is even possible at all.

The current trend of installation as an exhibition technique for painting responds to the need for originality and new demands from the contemporary art spectator. “Painting Forever!” at Berlinische Galerie boasted a gigantic wall installation from Franz Ackermann. His bright and intricate subjective abstracted landscapes and maps hung on the boldly painted walls in various methods, some on struts resembling billboards, another protruding out like a television screen. These viewing mechanisms reference the image-saturated global condition that challenge the idea of originality, authenticity, and the autonomy of visual arts. Ackermann makes the process of viewing art part of his subject. Dwarfing the viewer, the installation makes traditional modes of viewing physically impossible. In the press release the gallery emphasised the site specificity of the work, an aspect of installation that responds to criticisms of painting as a commercial commodity, delivering a one-off experience.

Sheer size also remains a successful way to impress. Finishing early this year, “Wall Works” at Hamburger Bahnhof showed a collection of imposingly large paintings and wall installations, including works by Katharina Grosse and Nasan Tur made specifically for the show. Tur’s work “Berlin says…”, 2013 was a giant rectangle patch of red paint made by spray painting text copied from graffiti around Berlin. In the treatment of process, where labour and production take import over form, context is everything. This work was accompanied by a video of the painting being made, crossing into a multi-media installation work. Grosse’s colourful spray painted installation of three huge uprooted trees appeared like giant paintbrushes marking the gallery walls. Grosse’s works often physically extend into and dominate their environment, however her recent exhibition at König Galerie, inaugurating the new St Agnes Kirche location, were all panel paintings. Her vibrant palette and layered spray-gun technique produced striking paintings worthy of the grand physical space they occupied. Though a traditional format, the large works spatially interacted with their surroundings.

Contemporary art exists in a post-studio era, where individual works are not simply considered and understood on the terms of the artist’s approach, but rather it’s all about exhibition: artworks are subject to interaction with the physical space they occupy and the conceptual planes they cross. Like all visual art, painting works are thrust into a compulsory relationship with the visual material of our daily lives, and are in dialogue with the ways in which we view and understand this material. All contemporary art is conceptual art. Even purely formal painted works are responding on some level to the postmodern condition of living in an image-saturated society. Contemporary artists can no longer make work that is viewed outside of the conceptual framework of image making itself. Many contemporary painters embrace the self-reflexivity of painting as a conceptual basis for their work, using art historical and media references to conceptually layer their work. In this acknowledgement – a critical engagement with its own history and with its position in a wider context of image making and circulation – is where I find painting as a medium has the most potential.

In trying to comprehend the contemporary art landscape and its rifts, an interesting avenue is to question the merit of a medium-specific approach to theory, criticism, and curation. Mono-medium group exhibitions and art writings work to reinforce painting as separate to other contemporary mediums and practices, maintaining its academic distance and institutional privilege, and hindering the medium’s development and its reception alongside new modes of art-making. Berlin’s art scene responds to a globalised art world, and to the new tools and modes of communication of that world. Painting as a medium is not fundamentally at odds with these trends, and so rather than asking if painting still has something to offer, perhaps the more appropriate question is whether traditional academic and institutional approaches to painting continue to be relevant.

POSTED BY

April Dell

April is a writer living and working in Berlin. She studied Art History and Film and Media Studies at University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand....

Comments are closed here.