Viviana Drugă describes herself as a Romanian ritualista who lives in Berlin and mainly focuses on performance art and photography. In her childhood she was close to nature and Christian-Orthodox spirituality, and these influences would later fuse with her later interests, in her mature art practice, coming after a period of satirical and politically engaged art, seeking new ways for the audience to discover their own selves through magic.

Magic and art have a common genealogy. For millennia they were inseparable. It’s hard to say when the current state of art began or if there ever really was a break in the relationship between the two fields, perhaps only less frequent intersections. In spite of this, within the circuit of contemporary art, the supernatural is present, most often in its performative formulas, through the social re-acceptance of astrology, through the use of the tarot, or of other divination methods, and through the development of healing methods (touch, massage, various kinds of energy exchange), as a means of clarifying one’s subconscious or overcoming grief. The use of magic in contemporary art also consisted in rediscovering ancestral forms of knowledge as means of resistance for oppressed communities or as resources for queerness. The image of the witch, an image which one can’t help attributing to Viviana, has been closely linked, in recent decades, to that of the woman in control of her own body, who strays from the known order of things.

I met Viviana a few years ago in Bucharest, when she organized a ritual commemorating her uncle’s passing. Together with some friends of hers, we took a walk through the early 2016 snow, from the Old Center to Carol I Park, during which Viviana had conversations with her dead uncle. We each held a rose that, when we came to the end of the walk, we had to bury in the snow while making a wish for the coming year. Throughout the years we intersected briefly, but recently I realized I had to get a more comprehensive view of her practice. The interview that follows is the result of this attempt.

To be able to talk about magic practice, in this case integrated into an art practice, we also need to talk about the origin of things, about your childhood influences. Tell me more about the environment you grew up in.

I grew up in Făgăraș, where I stayed for school, and in Voivodeni, where I spent all my holidays. In the city, I went to the German school, though my parents did not speak the language, and, in the countryside, there were my grandparents, the mountains, the river, and the trees. We couldn’t wait for the holidays to run there like it was paradise. Learning German at school was my mother’s choice. She wanted to have two blue-eyed, German-speaking girls. Done and done: my sister and I were sent to the German kindergarten, then to the German school, without my mother and father, or anyone in the family, speaking the language. We did our homework as best we could, because all subjects were in German, apart from Romanian class, so they couldn’t check them. It was like schizophrenia. At home Romanian, at school German. My sister any I almost developed a secret language, a combination between German and Romanian that only we knew. This was my first evasion of reality that I would later recall, after coming into contact with other artistic-magic languages. I spoke Romanian well, while I always viewed German as a sort of shirt that I was forced to wear. It was a few sizes too big, and I never mastered it until I left Romania for good. My teachers were Saxons – descendants of the Austro-Hungarian occupation which lasted 700 years in Transylvania. Their German was local, provincial – a German my grandmother would have spoken – as I was later to learn in Berlin. But it didn’t matter, so long as I had my grandparents and the heaven in the Făgăraș mountains. I couldn’t wait for the three-month summer holiday: 15 June to 15 September. Tschuüss, city. See you! Goodbye, German. Goodbye hassle.

In that magical place I really came to life. My upbringing had a huge influence on what I am today. This rural area was the first place I experimented with and in nature. Unlike in the city, there were infinite possibilities to explore there: cold rivers rolling mountain rocks, trees to climb and make into a one-day home, almost nobody around apart from the peasants working the fields. An archaic environment that has remained unchanged for maybe hundreds of years. The beginning of things. My sister and I were practically alone in an endless landscape. Also, our grandparents were quite lenient with our education, so they let us do what we liked from morning to evening. I remember once wandering the whole day from one village to another and stopping next to the river, where we sang all day like it was Eurovision, with wooden microphones. We sang and rated each other. It was awesome!

Sisters, photography for the camera re-enacting a childhood setting, 2011

The fact that I was in the village of Voivodeni in the summer but also in the winter holidays allowed me to take part in seasonal holidays. Those that took place in winter were going caroling (colindatul), where we went from door to door and sang Christmas carols, holding an instrument with bells and images of Jesus and Mary called a viflaim, made by our uncle Gheorghe, a history teacher. Even though the lyrics all talked about the birth of Jesus, some elements of the folk rituals around Christmas time are probably of pre-Christian origin, rooted in the Roman Saturnalia and the pagan holidays of the winter solstice and connected to the fertility of the earth. There was also the summer holiday of Sânziene (fairies), corresponding to summer nights’ dreams. We slept with lady’s bedstraw (sânziene) under our pillows to dream of our future husbands. For a 5- or 6-year-old kid, all these rituals in which we also performed would encourage me to later construct my own productions.

My education was also influenced by Christian Orthodox thinking, with strong pre-Christian origins, in the village where I spent a lot of my time – that was my father’s side of the family – and with mystical Orthodox values based on visions and trance from my mother (originally from Moldova), which formed my basic trajectory growing up. Mother would spend hours in church, praying. The lights were dim, and all the burned frankincense turned everything into a misty, obscure setting. You can’t imagine the atmosphere if you don’t go to an eastern church like that. It’s very medieval, nothing to do with the 45-minute mass of a Lutheran church. This kind of church inspired me to recreate this atmosphere in my personal exhibition CONFESSIONALS 2019. That and the idea of confession. A secret placed safely in the heart of another.

Mother loved Father Arsenie Boca. Even though she never met him, it was as if she talked to him every day. They said that when you came to him, Father Boca already knew everything about you, he read you like a book. His hermit cell was, for a while, located in the mountains, on the path to Cabana Sâmbăta. Whenever we went hiking through the mountains, mother would remind me of the place from which Arsenie had prayed for us, and father would show us the earth-dug home of the Hașu brothers, my grandmother’s brothers on my father’s side, hidden by the river to not be found out, because they were part of the dissident group of Țara Făgărașului. Both were caught in the end, and they paid for it with their lives. They were only 20 years of age. Basically children.

I’ve been talking about my childhood because in my adolescence I had my big existential crisis, and, in a way, all the years after have been marked by it. In other words, I had a bout of teenage depression that lasted for a good 2-3 years, during which time I discovered Emil Cioran, so I didn’t get better thanks to him. Complete nihilism. Everything was pointless. Well, the path from Voivodeni to Cioran is one you don’t return from, so I had nothing more to do in the countryside, though I wasn’t friends with the city either, not to mention that school still stressed me out – the German language and the fact that I hadn’t fully mastered it. After my crisis I didn’t really return to normal. Instead, I became very punk. I remember being in high school, in 11th grade, and we celebrated New Year’s at my grandparents’ house in the country. Since they had passed away, the house was practically empty. I invited only psychos, we listened to Marilyn Manson and Nine Inch Nails. Uff. After we ran out of food, we were debating who’d kill the rooster to make soup. I yelled: not the rooster! So, they cut a chicken instead and I offered to remove its feathers with pliers because we didn’t think to scald it. Barbarians! We burned the firewood axe because we were too lazy to fetch wood. Everything Nihil. There were nice moments too: I remember how we tied our sleighs to a tractor to pull us from one end of the village to the other. Oh, how we yelled from joy – and probably too much wine. I was grounded for a while after that, and I’m glad of it now. My poor parents…

The period in which you worked as an artist in Romania was one when mysticism was in a latent state, I imagine. Could you please describe the twists and turns that your life as an artist took and your intellectual development in this stage?

I lived four years in Sibiu, four in Cluj, and four in Bucharest, including high school, university, and the post-university period, which overlapped with my mother’s cancer – I chose the latest city only because there was a direct train to Făgăraș so I could visit my mother. The world works in mysterious ways when you have money in your pocket: you want to get on a train to Berlin from Cluj but you have a bad dream telling you not to and that same morning your mother calls you to tell you she has metastatic cancer. In retrospect, Bucharest brought me a lot. Before I’d encountered it, I only knew Transylvania. I’d kept a certain distance from the south, because of the urban wilderness that was Bucharest, at least how I imagined it. This wilderness weighed heavily on me the first six months, augmented by the anxiety connected to my mother’s illness. The political situation was also wild. But, in the old part of town, I discovered an absolutely magical atmosphere. The way in which Armoniei Street flows into its sister street. The feeling that you never go down the same path twice or that you don’t know what you’ll find after turning the corner. Here, in this mysterious and mystical – but also very corrupt – environment, is where I discovered my vocation. I discovered that the camera is a weapon that can capture you in action. Actionism. Performance art. Photos with Romanian president Traian Băsescu in 2006 wearing a red balaclava knitted by a granny. A flash mob with naked people at 6 in the morning in Revolution Square with the palm trees planted for 30,000 Euros with one goal: to win the local elections. A communist backdrop, palm trees in the front. Kneel, Romanian, before the symbol of fleeting capitalist kitsch. You couldn’t but be politically and socially involved! Boris Groys was on my nightstand. That was in 2006. Until then I hung on. It was life and death, and after mother passed away, I took the first ride to Berlin. Romania spiritually drained me with that vital loss. I’ll never recover, but now I can say that, having become a mother myself, I have incorporated it.

Viviana Druga, Passive Guerilla with President of Romania Mr. Traian Basescu, Bucharest, 2006

Berlin brought you what you describe as “freedom.” What do you mean by this?

I was a tabula rasa when I came to Berlin. I was a wasteland. Everything that came after was limitless joy. I was freed from myself, from the past, from pain, from belonging, from the gene. I could be anything in this stage city. Stadt als Bühne. When the wall fell, the whole city was like a pile of rubble: collapsed buildings, apartments with holes in them, but there was also an incredible freedom to sow something new. Everywhere you looked, even though it was already 2007, there was art. The people, buildings, words, everything. What followed were 10 years of astounding inner transformations, in my mind and soul. I opened myself completely to these new creative manifestations of being. There was an immense need for Freedom.

Magic openly made itself felt in your art when you focused on understanding the tarot. I am curious about how it came to you and how this process of understanding and restaging this magical system unfolded.

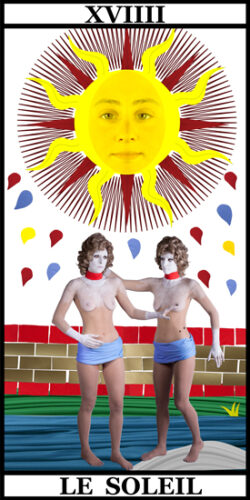

I turned to the Tarot out of a curiosity to understand the symbolism of the Marseille Tarot. I was very interested in that tarot in particular because it is one of the oldest recorded sets. It seems to have originated with nomadic tribes from Egypt, carried by travelers before the Library of Alexandria turned to ash. It traveled to Italy, where the French discovered it, in Piedmont, and brought it to Marseille, hence the name. Because I couldn’t understand it only from books, I had to come up with a better strategy: I had to stage it like a performance, with real characters, costumes, props, drapery, and setting. As I was already living in a house with ample space for such an action, in Torstrasse in Mitte – which I had gotten through a friend, and my sister was also temporarily living there, another mystical phenomenon – I had plenty of space to play with together with the designer I collaborated with, Tata Christiane. Basically, I used many elements from my home: the kitchen table painted blue, the ladle sacrificed as a prop. I didn’t organize 31 people from 17 different countries – a human collection I will end up having – but I took the time to find people resonating with the card they would be performing. Every future character received a personal invitation to take part in the project. If the answer was affirmative, we would schedule a photo shoot. The whole process took four years. I didn’t rush to make decisions, instead waiting for the so-called divine time for every action. I don’t think I could have arrived at the same understanding if I hadn’t lived and created every element in the composition myself. Learning by doing. That’s what I think happened. Basic magic, forging something with the fundamental elements of nature.

Viviana Druga, 22+1, Tarot de Berlin, photo-collage resulting from 22 performances, installation view Somos Berlin, 2014

What’s amazing about the tarot is that it contains elements from Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. It is a blend of all three religions, a kind of religious tolerance that you can’t find in such an original way anywhere else. If the basis for the tarot’s working could apply on a political level, the world would be completely different. But we’re far from something like that. In fact, lately, there’s a tendency towards our differences and not our similarities. What interests me in every magic act is precisely that it situates you in a tolerant position, and I see every act of divination as a sort of prayer to a saint. It’s like establishing a connection to a divine power, to something greater than you, in order to achieve communication in order to heal or soothe a person in need. The person doing the divination is only a conductor through whom energy passes through, nothing more. The biggest mistake would be to believe that you’re the one performing and weaving the divinatory narrative. You are not performing, you are being performed. You are directed based on color, similar to the canon of icons; the position of the head and hands is very important. If you follow this visual path in order to conduct an x-ray of the soul and you allow yourself to be led without intervening rationally, you can’t be on the wrong track.

The influence of various artists or thinkers can’t but show itself in your work. I’d like to know what resources they offered you.

Of course, Jodorowsky is the granddaddy of western tarot. He reads the Major Arcana, especially the Tarot de Marseille. I had the opportunity to offer the master a T-shirt with my tarot when he came to Berlin to present his film Poesia sin Fin. From him I learned that the tarot is a magic act, that without poetry life has no meaning, that without personal sacrifice you can’t turn shit to gold. I’ve been influenced spiritually by many people I’ve met or haven’t met: philosophers, artists like Louise Bourgeois, Niki de Saint Phalle, Leonora Carrington. Leonora seems to have stepped out from a different world, and how she survived the war and took refuge in Mexico feels like I was there living her past. Niki worked for 50 years on the Tarot Garden in Tuscany, with Jean Tinguely taking care of the mobile parts. Personal sacrifice for art – that is what touches me deeply. The ability to create a cosmos and a personal mythology that are so strong they shake your version of reality. What is reality but a consensual hallucination?

Your performances have also had an animist component, like the one in the Sahara, which makes me think back to your childhood contact with nature. It’s like a circle where things from your distant past have returned in a more refined form, impacted by the experiences that followed.

Yes, animism is the basis for a union with something greater than us, a kind of divine breath in which all forms of life exist, from plants to animals. The divine breath exists even in stones, and the fact that volcanic eruptions are born from a warm spring underground makes us think that even stones have a heart. The Sahara invited me twice to step onto it. The first time, I felt I had Fata Morgana constantly, as the environment completely took me in. I disappeared like that Chinese artist disappeared into his own painting. Suddenly you are no more, you no longer matter. You are a grain of sand in the desert. Today you’re here, tomorrow you no longer are. To make love to the desert is a metaphor that I like to use when I want to suggest precisely this disappearance into something you have created. Suddenly you are no longer yourself, you are part of something greater and overwhelming. Like when I was in the countryside in the Făgăraș mountains, and every day my sister and I decided which direction to walk in until we could walk no more. Then we had to get back, before sundown, oftentimes starving, but with our minds open to every clue. Nature, the trees – they were our friends, because didn’t have many kids to play with there, or maybe we didn’t get along, or maybe we were enough for each other, with our secret language in the middle of the wilderness. To return to the desert: escaping the I is my greatest liberation. That is why I chose the medium of performance – to disappear little by little every time I enter the “zone.”

Back to Earth, performance Sahara desert, Morocco 2013-2014

How do you perceive time when you’re performing? What are your feelings when you exhibit yourself? (“The adrenaline before something you care about,” you can also talk about the “I love you” in China, the artist as a medium, with power over the aura, and don’t forget about tuning in to the order of things.)

The Zone is a term in Tarkovsky’s Stalker. It is a place where extraordinary things can happen. A posthuman, post-war, post-time, post-space, post-loneliness, and post-sadness zone. Perhaps that’s just my interpretation, but I see this zone as very similar to the zone you enter when you perform. A non-time, a liminal space, like something out of the Matrix, to use some contemporary terminology – after all, my son is named Neo. This sacred time is the same as in childhood, lacking self-observation. The moment you enter the zone, time not only becomes suspended and slowed down, but you also get in tune with this slowness, allowing you to see the energies and states of others more clearly than in real time, and you can influence events towards the good. It makes me think of something that happened in China, in the Czech China Museum, where I was in the middle of a performance with artist Han Bing, having climbed through a hole in concrete like an opening towards the street. I was painted completely in black, and he/she in white. Together we formed a perfect, harmonious circle, yin-yang. As soon as we began throwing flowers at the viewers, the police came and asked us to stop the performance. In a fraction of a second, because I was still in that sacred time that I did not want to end prematurely, I said the only thing I knew in Chinese: wo ai ni – I love you. The officer looked at me stunned and allowed us to finish our performance, without taking us in or asking for our papers.

Viviana Druga & Han Bing, Tao Rebirth, Czech-China Museum, Beijing, China, 2017

In another recent video interview you said that “now we’ll have very interesting things, in art and in all kinds of zones… not yet, but they’ll come.” I find what you said intriguing and it is the motivation for my questions. As far as I know, the project you are currently working on is connected to memories of your origins.

At the end of April, this year, I will prepare a clay sauna inviting you to strip naked and confess yourself to a stranger. Well, this earth sauna is a reference to this hiding place, a safe space.

Starting from the Finnish proverb that says that “there are only two things a sauna can’t cure: death and a broken heart,” SAUNA CONFESSIONS is conceived as an eco-feminist remake of the Christian ritual of baptism and confession – the exorcism of sin and trauma in order to recover ourselves. The “sauna” is a purging, but every day, ritual extracted from Finland’s pre-Christian shaman culture. An Orthodox baptism in Transylvania consists of two parts: exorcism and blessing, the collapse of the good-evil duality, the integration of the darkness, rather than its banishment – recognizing its inherent divinity. SAUNA CONFESSIONS puts the participant in control of their process of rebirth. This inverts the psychoanalytic process (the analog of modernism and Christianity), where the participant seeks control over their narrative through the analyst’s mediating authority. Instead of becoming attached to a narrative, we accept, liberate, and transform.

The exhibition will take place in Berlin at Galerie im Saalbau, between 29 May and 19 June, with the opening on 29 April at 6 pm, for which I will have a performance. More info here and here.

What “interesting” things do you think will happen, especially in art, given the limits that we all feel in the present?

When I first talked about these things, the Russians had not yet invaded Ukraine. Now we’re in the middle of a war. The pandemic has also been a war, and it’s far from over. A different kind of war, but still a war. Interesting things are oftentimes not pleasant things. I worry that what will follow will make us question our faith in the world completely. The production of arms is at its peak. Why do we need another war? Is bloodshed a blood ritual for men, a replacement perhaps of women’s monthly one? Besides that, we live in a moment where old structures no longer work. Official rules, politics. We are fundamentally in a spiritual deadlock. Or maybe this spiritual crisis is caused by the void in which many of our contemporaries have fallen as a result of a heartless capitalism. Many, no longer seeing meaning in cities, retreat to the countryside, seek land, want to plant vegetables, olives, anything you can make with your own hands and that gives you a much greater satisfaction than staring at a screen all day. I hope that in art we’ll see more interesting works with a more responsible approach to their materials and maybe also able to overcome the Me! Me! Me! in favor of a WE, of the Global instead of the Singular. I can only hope…

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Bogdan Balan

Bogdan Bălan is a cultural journalist, art critic and cultural worker. He has collaborated with Goethe-Institut, Savvy Contemporary, Scena9, among others....

Comments are closed here.