When something is poorly done, often outdated, we classify it in our small local artistic ecosystem under the label of “uap-ist”[1] work. But the greatest evil of the cultural apparatus is not the existence of these out-of-place-and-out-of-time productions, but, I believe, a less visible one: the derisory nature of anomie[2]. A kind of silent killer, like the Naegleria fowleri amoeba. I am reminded here of instances such as the Sokal hoax or the principles of cultural mediation. We do not feel the need to ask a mathematician to explain why the formula 1+2+3+…+∞ is equal to -1/12, which we would say is counterintuitive; but we find it necessary that all texts accompanying exhibitions be no longer than one page, or that we criticise terms such as gesamtkunstwerk, processuality, or even indexicality as “obscure.”

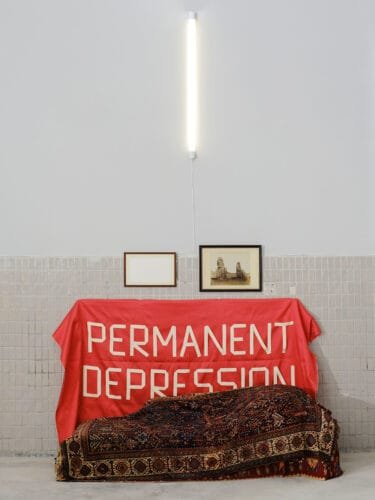

I will talk about such tropes in relation to the exhibition “Unleashing the Sins of Sculpture,” curated by Georgia Țidorescu and Cristina Vasilescu at Scânteia+. And I feel the need to mention it, because the exhibition was positively reviewed in Frieze Magazine, which might seem like a kind of approval în our small world. I will refer here, somewhat abruptly – because the format of this text is also conditioned by the aforementioned “one page” – both to the misuse or forced use of the very central concepts on which the exhibition is based, and to the grouping of the female artists under a convention of proximity and accessibility rather than one of representativeness.

The exhibition text begins with the statement “sculpture is more present than ever.” The problem is not that this is profoundly wrong – sculpture may have been inflated under communism, where this art form, which creates stature and presence within the symbolic site-space, transforming something small into something large, as in all authoritarian political systems, was dominant – but rather that there is a widespread confusion between installation and sculpture as art forms. Installation, as a medium of expression, is not a new form of sculpture, nor even an exclusive continuation of it, but a genre and a continuation of all the others; a new instance specific to the postmodernist post-media condition. To associate it with sculpture simply because it is three-dimensional is like associating video works with painting on the basis of their two-dimensionality. Let us quote Claire Bishop here:

”Installation art therefore differs from traditional media (sculpture,painting, photography,video) în that it addresses the viewer directly as a literal presence in the space. Rather than imagining the viewer as a pair of disembodied eyes that survey the work from a distance,installation art presupposes an embodied viewer whose senses of touch, smell and sound are as heightened as their sense of vision.”[3]

As for the concept of the expanded field addressed in the exhibition text, it is used by Rosalind Krauss, who coined it, to refer to a generation and a set of artistic practices that pushed minimalist sculpture into the field of architecture and landscape, in a new logic: site vs. non-site. We don’t really have such instances here.

In terms of representativeness in the exhibition, if we look at the list of nineteen female artists, in terms of sculpture – but not entirely, rather in the practice of recent years – we can say that only Larisa Sitar and Ileana Pașcalău can be identified, and in the field of installation, Apparatus 22, maybe Andreea Medar and Kristin Wenzel. Many of the artists present use specific genres that rarely intersect with installation, and not at all with sculpture: mediums such as graphics (Alex Bodea), photography (Pusha Petrov), or ceramics (Lorena Cocioni).

To complete this anomic principle, there are also a few mistakes in the display: the podium for a performance installation by Arantxa Etcheverria is used as a pedestal for one of the mannequins in the work of The Bureau of Melodramatic Research; a work which is itself incomplete, due to the absence of the video with the performance that explains it; and the wall on which Ioana Nemeș’s (reconstructed) textual installation stands is not stand-alone, the other side of it exhibiting… what else, but paintings.

[1] uap-ist: a pejorative term referring to the art of members of the Union of Visual Artists of Romania.

[2] anomie: a term first defined by Emile Durkheim in 1894, which has been used in social history and theory to describe certain historical formations of social deregulation, a condition defined by the uprooting or breakdown of any moral values, standards, or guidelines to be followed by individuals. Transposed into aesthetic and cultural debates, the term “anomic” identifies the working conditions of cultural producers for whom utopian avant-garde aspirations, or even the desire to have minimal socio-political relevance, have disappeared. Culture in conditions of anomie acquires, at best, the characteristics of a simulacrum of legitimacy and prestige and, at worst, those of a closed circuit system of expertise specialised in investment.

[3] Claire Bishop, Installation Art, Tate, London, 2011, p. 6.

“Unleashing the Sins of Sculpture” [Suprainfinit Gallery at Scânteia+, Bucharest, 27.03–08.05.2025]. Artists: Apparatus 22, Andreea Anghel, Alexandra Boaru, Alex Bodea, The Bureau of Melodramatic Research, Lorena Cocioni, Giulia Crețulescu, Arantxa Etcheverria, Andreea Medar, Hortensia Mi Kafchin, Ileana Pașcalău, Pusha Petrov, Adriana Preda, Lea Rasovszky, Ioana Sisea, Larisa Sitar, Mona Vătămanu & Florin Tudor, Kristin Wenzel. Curators: Georgia Țidorescu, Cristina Vasilescu

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.