For centuries, folkloric tales were intended as a cultural instrument to teach one how to protect oneself in a precarious environment. The boogeyman is one of its central characters and embodies who or what is the danger. As a communication network for transmitting information, storytelling has become technologically obsolete. It has been replaced by waterfalls of updates, favoring the evolution of a disorienting information-jungle. Each act of terrorism is a national shame, any degenerated fanatic who kills is an evil creature that slithered into our world. Unless it is a white, Christian person, and then is just news.

Through the built-in blind spots of objective politics, rational human thinking, rules and dogma, a wild aggression takes shape; from a defensive mechanism, the boogeyman becomes a trophy animal. It is presented as a cultural justification for the protection of hegemonic power. The Omul Negru exhibition, held at Nicodim Gallery in Bucharest, brings together works by thirty-four problematic artists with subjects on hierarchization, cultural hegemony, the control of knowledge, and the visual forms these take in the informational and human communication network. It begs us to raise a meaningful question for today’s reality: how has the perception of “the other” changed in the spectacle of collective fetishism?

The Omul Negru exhibition is a shadow play in which the curator Aaron Moulton takes the role of a storyteller. The narration brings forward a direct confrontation between the 21st century’s visual culture and a system of societal morality that has developed over time. It guides one deeper and deeper into the darkness of an allegory, grotesque in its abundance of visual clichés. The fear of the other is teased and tested in a cabaret speech with an occult halo that plays with our inherited presumptions of belief and truth. A heterogeneous space is unleashed, unifying the internet and geographical, cultural and symbolic dimensions. The curator’s Youtube channel trumpets signs of danger (Omul Negru – The Omen Trailer) and whispers a hymn of war against the hegemony (OMUL NEGRU — The Omegamale Trailer). The choice of time and space for the tale’s beginning implies universal superstitions and beliefs (be they the vernacular richness of folklore and oral tradition, or as epitomes of ignorance). A pagan ritual of sacrifice takes place before our eyes, displayed on the high definition retina of the personal mobile (OMUL NEGRU – Chunga Exhibition Walkthrough). The storyteller, thus, makes us not only see that the boogeyman is, but also how it is.

The scientist Richard Dawkins declared in The Blind Watchmaker that “if you want to understand life, don’t think about vibrant, throbbing gels and oozes, think about information technology.”[1] What this observation highlights is the mediation process that takes place in our engagement with information. As in the situation of listening to a story, what we are find out is dependent on the data the narrator offers us and is influenced by the manner in which he displayed the premise. In John Houck’s Portrait Landscape (2015) we see the psychological phenomenon of pareidolia superimposed on the errors of facial recognition software. This poetical reconciliation between the human mind and technology reveals that we see what we are programmed to see and then we believe that what we observe is what we are supposed to see. However, it is common sense to say we know there is not a human face even though it is instantaneously perceived as being one. Both logic and belief collide in reasoning – a phenomenological process of envisioning models of situations, as supposed by proponents of the mental model theory.[2] In Omul Negru, we discover this mix between formal logical structure and unjustifiable belief in a complex dynamic interaction. It constructs both the critical discourse and the believability of its own system in an unexpected way.

The visual discourse of Omul Negru take us through doubt and suspicion towards the equation between weirdness and ugliness as signs of a dark transcendental power or imminent dark powers of an object. Instead, the boogeyman is proposed as a mechanism of control that establishes a hierarchy of power. In 100 Reasons, the collaborative video work of Bob Flanagan, Sheeree Rose and Mike Kelley (1991), one hundred appropriate names for a paddle become rosary beads. Its imposition generates an antinomic structure, one taking the status of the sinner and the other, a legislator. Husserl’s phenomenology gives us a more adequate articulation of this relational vision. He states that what is concrete in the world we live in is relations, and what we call “subject” and “object” are abstractions of these concrete relations. The work of Benja Sachau has in this context an awe-inducing impact. A sound recording is played at 60 minute intervals in the background – FBI QO42 (That’s Right!), 2010, blasts the euphoria of the population of Jonestown, Guyana, in its last minutes of life. The power relation that gave mass control to the leader Jim Jones is revealed as a concrete mechanism which ventriloquizes the collective hand to commit suicide in the each individual case.

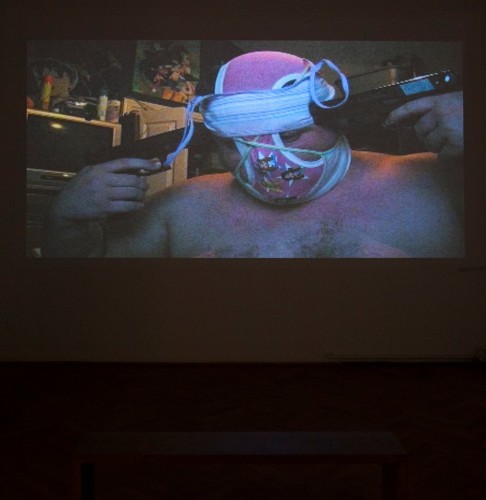

The formal pattern constructed by Aaron Moulton is precisely centered on revolt against the bureaucratization of religious belief and the distinction between “objective knowledge” and “subjective experience”, the ethical-ideological hierarchy and cultural hegemony. Of course, none of their characteristics manifest themselves in a pure state. On the contrary, each of them mixes together with the others, subject to the laws of interdependence – a dynamic is created in which one is only transformed by modifying the others. It functions as a progressive accumulation of mental images. With each step we take into this public space of the collective imagery, evil is revealed in new semantic. In Brock Enright’s video, Wellwater (2005) is the image of an erotic abandonment in the face of power. The passion and powerlessness expressed on Enright’s face challenges us to see Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-52) in a contemporary aesthetic. The divine will is replaced with the violence that characterizes a decisional system. The scene of ecstasy is transmuted in a cliché frame with which drama movies made us familiar. The innovation Enright brings is the critical shift from artistic production to understanding the causal conditions of perception. He constructs a minimal scenography: a close up screening of a facial expression with an abrupt final scene. By engaging both cultural and visual memory through the vague depiction of a suicidal scene, he makes us believe we see it. Wellwater, thus, highlights the agentive entity that mediates this process and its effects on reason: the memory. But the certainty we have over the subject of the video is distracting the attention from the actual situation with which we are confronted.

Through the exhibition, an intriguing hybridization takes place between the curatorial practice and the artistic production. We see the cynical nihilism of Omul Negru’s visual discourse making its way on a new route under the halo of gnosticism. Lazaros’ ritual actions (***, 2016 and the summoning of Ed Gein’s spirit on 6/06/16), Max Hooper-Schneider’s symbolic sacrifice (Pet Food Effigies, 2016 and the video The Canine-Grade Effigy Trailer) or the display of cryptic-esoteric signs in the gallery’s space (Brian Butler, Circle and Triangle of Art for the Evocation of Bartzabel, the Demon of Mars, 2012) realize the superimposition between reality and fiction. Cultural memory, visual clichés, religious belief and superstitions are intended to open “the Pandora’s box” of human irrationality. Thus, we find ourselves following a critical thought pattern deviated to a (more or less) believable, but absolutely illogical conclusions – as the occurrence of a supernatural event. This is Omul Negru’s dark punch line: we live in an age of lazy thought. We choose, instead, to use clichés from pop culture or literal depictions in our interpretation of reality. Thus, we see ourselves at our most weak: when we are confronted with our fears, we are satisfied by the very first conclusion, reflecting our inherited cultural habits. The more believable the end of the story is, the less we will ask ourselves if the logic of the story was also valid – susceptibility to invalid syllogism, so to speak.

The hard truth Omul Negru reveals is the vulnerability which characterizes us in front of a believable story and the archaic critical apparatus we use. When confronted with a folkloric narrative, we can be skeptical. Our culture for rationality has developed a hypertrophic sense of rationality and disbelief in the other, demanding proof before making a statement on the veracity of a story. Today, informational networks gives us the possibility to listen to live-streaming narratives, cases in which we appear absolutely naïve and blinded by the bi-dimensionality of the image. The curator Aaron Moulton, through this exhibition, offers images of a diverse collection of modern times’ human monsters. We are required to see the value systems behind our judgments and how this boogeyman-archetype is migrating, transforming in the virtual informational system. Omul Negru is a story within a story. The narration reveals the fear of the other as a political matter through the power it offers to the one who instrumentalizes it. However, there is a chameleonic structure that Moulton creates for letting us see the ideological aspect of the boogeyman, which camouflages between the values of a different thinking system. The intention is to make us perceive the consequences of equating the word with the image, and the image with the proof. In a bizarre way, one could say that our ultimate desire is to satisfy the narrator, as we are part of his dream before accepting the story as being true or not.

In the digital era, to communicate a story suppose the transgression of the frontiers between reality and fiction, image and information. We are already living in an augmented reality. In this new world, the Omul Negru exhibition makes us aware of a new applicability of the boogeyman, a hubris-crazed monster with a structuralizing force: to confer believability on a story. In front of this seductive allegory of the story as an information system, we are offered a bewildering experience; and find ourselves disarmed and awakened, somewhere in this Land of Opportunity and Self-Fulfillment. Boogeyman is dead, long live the Boogeyman!

[1] Richard Dawkins, The Blind Watchmaker. Why the Evidence of Revolution Reveals a Universe Without Design, W.W. Norton & Company, New York and London, 1996 (1986), p.112

[2] Johnson-Laird, P.N., Legrenzi, P., Girotto, V., Legrenzi, M., Caverni, J., “Naive probability: A mental model theory of extensional reasoning”, Psychological Review, 1999, Vol. 106, No. 1, pp.62-88

Omul negru was at Nicodim Gallery between 6 June – 7 July 2016. It is the first part of a folkloric trilogy, entitled The Trito Ursitori.

Artists: Daniel Albrigo, Will Boone, Mike Bouchet, BREYER P-ORRIDGE, Gunter Brus, Brian Butler, Church of Euthanasia, John Duncan, Damien Echols, Brock Enright, Bob Flanagan, John Wayne Gacy, Ed Gein, Adrian Ghenie, Douglas Gordon, John Houck, Jim Jones, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Ted Kaczynski, Daniel Keller, Mike Kelley, Lazaros, Lionel Maunz, Asger Kali Mason Ravnkilde Moulton, Alban Muja, Ciprian Muresan, Steven Parrino, Hamid Piccardo (Marco Lavagetto), Ana Prvacki, Jon Rafman, Sheree Rose, Sterling Ruby, Benja Sachau, Max Hooper Schneider, Richard Serra, Robert Therrien, Ecaterina Vrana, and Zhou Yilun.

A full-color catalog with texts by Aaron Moulton, Alissa Bennett, an interview with Dr. Philip Zimbardo, an anthology of evil words and images has been published by Nicodim Gallery.

POSTED BY

Carmen Casiuc

Carmen Casiuc (b. 1994) is an independent art researcher and critic working with ideas and actions that ignite the role of imagination in theoretical science. She studied History and Theory of Art at...

1 Comment

A remarcable interpretation of a difficult and disputable group exhibition in Bucharest.

Magda Carneci