Fascination with poverty and misery and its subsequent frequent exploitation in art, (still) a primarily middle and upper class endeavor and preoccupation, is well documented and certainly nothing new. Not surprisingly, it manifests itself predominantly and most clearly in mediums which, historically speaking at least, have the value of document inherently attached to them, such as photography or video, where the pretense of “capturing reality” persists to this day, often functioning as pretext. Romanian artists are no strangers to this phenomenon, especially given the context of the former Eastern Bloc, where a post-communist environment and an arguably failed transition created dire socio-economic conditions for a considerable proportion of the population.

In the local scene’s recent years one odd case of such artistic exploitation is that of photographer Mihai Barabancea, who has been enveloped in various levels of scandal from the very beginning of his career. The peculiarity stems first and foremost from the number of occasions in which he was offered a platform for his work, leading in time to repeated offenses, deontological missteps, exploitative and at times outright deplorable behavior, both towards his subjects and his collaborators. It’s a particular situation demanding a somewhat more in-depth look, analyzing the work itself, his approach in creating it, and the claims surrounding it (both his and others’). His edgy persona started developing, in the art scene at least, around 2013, when I was hearing more and more of him as this promising but troublesome young artist, even with such accounts of him getting on the roof during the opening of one of his exhibitions, threatening (or joking?) to jump. It’s such stories he will in fact come to benefit from throughout his whole career, learning to use them to his advantage and probably being fully aware of how efficient it is to instrumentalize transgression whenever possible in today’s dreadful attention economy.

Nevertheless, his real problems began after the 2015 launch of the Overriding Sequence photobook. A superb object-book sporting remarkable attention to detail in craftsmanship, design, photographic selection, and (as its title suggests) sequencing, it didn’t take long for it to make waves in the photographic community. It would also cement Barabancea’s style, photographing people situated on the fringe of society, resembling Boris Mikhailov’s Case History series, but applied with care to the book format and the Romanian context. All this considered, a little more than a year after the launch, a startling blog post was made on the personal page of photographer Mugur Vărzariu – a character who, ironically, himself created a career out of frequently exploiting misery, albeit in a more well established and socially accepted fashion through regular bland photojournalism (Renzo Martens’s 2008 film Enjoy Poverty is probably the best explanation yet of how this functions). It had the inflammatory title of “State Funded Childhood Pornography,” and it quickly achieved its goal of gaining traction and making rounds on the internet. The accusations in the title are somewhat ridiculous for anyone with a whiff of artistic training, pornographic intent clearly not being present, Vărzariu rather choosing to obfuscate the whole point of the book by using a single image from it. What truly generated feelings of disappointment throughout the artistic community, however, was the revelation that most of the photographs were staged in one way or another, in spite of Bogdan Ghiu’s foreword stating otherwise, confirming the suspicions of many at the time actually. Disgust also made itself felt, as it was clear this was frequently done with complete disregard for his subjects, Barabancea sometimes also offering drugs or money in exchange for them posing. Needless to say, these facts brought grave ethical and deontological problems for the project.

Some time had passed, the issue appeared to be forgotten, and he was offered another chance and platform in 2017 with the production and launch of The Kiss – another impressive object-book production, catering also to blind persons through the use of varnish and Braille writing. Trying to come ahead of similar accusations to the ones faced in 2016, he came up with ingenious concepts such as ”hyper-reality-hacking” and ”guerilla-style photography,” admitting to the staging factors in his practice. This project would nonetheless prove problematic too when, trying to promote it, he released making-of videos in which it was clear the process involved more ”guerilla” than ”style,” not only staging photographs, but in actuality often aggressively forcing situations and subjects (even kicking them in order to start a fight) until he obtained the shot he wanted. It once again demonstrated his deplorable behavior towards the very people on the fringes of society he so adamantly claims to stand by. The contrast was much too stark this time for the community to forgive him any time soon. The next scandal, although extremely minor, would be a decisive blow for much of the reception of Barabancea’s art – an advertising pictorial created for the Bucharest expensive footwear shop Sneaker Industry. In it Barabancea deemed fit to use an eccentric old fiddler as model, staging photographs in ghettos around Bucharest to better sell original Nike sneakers. In other words, he exoticised precarity and a frequently discriminated-against racial minority (as fiddler culture is closely connected with Roma people in Romania) to better cater to middle and upper class consumption habits.

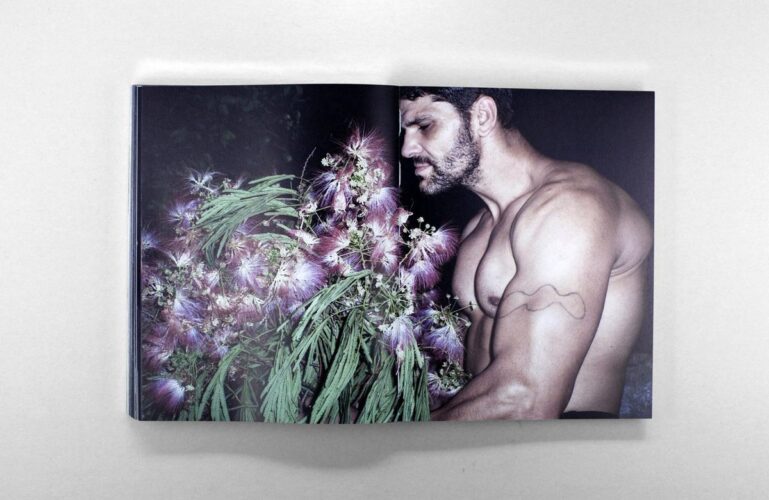

I think, in order to better understand the repeated chances Barabancea has been offered to show his work, it’s important to examine the allure of his photography and the artistic context in which it operates. Among plenty in the photographic community the consensus is quite clear – extremely good work, real shame about the person and the “creative” process behind it. What I’d argue however is said work would be unattainable without Barabancea’s problematic approach towards creating it, losing its attractiveness otherwise. In the Romanian art scene there is no other such perspective upon the fringes of human society, on people and communities forgotten by the “civilized world.” Virginia Lupu does an amazing job, working with these communities via photography in apparently similar fashion. On closer inspection though it’s clear that while her projects denote warmth, community, and support for the persons involved in them, those of Barabancea denote agitation, grime, violence, abuse of both substances and people (occasional uncanny tenderness is also present, predominantly in The Kiss). In other words, while one represents genuine care towards the subjects being photographed, the other is dedicated to creating tension and bringing to surface the squalor felt on a day-to-day basis by those traditionally excluded by society. He reveals the misery we know flourishes beside us, but which we actively avoid perceiving except in a controlled / safe form such as a photobook or exhibition.

Unfortunately, Barabancea is able to do this so effectively by specifically employing aggressive force and creating problematic situations himself in the process. It’s the secret ingredient to the impact of his images, generating so many uneasy emotions. Elements like violence, squalor, and abuse are always ready to burst out of the frame, precisely because they’re inherent in his practice. He ingeniously reveals a hidden world, but is able to do so only at the extremely high cost of exhibiting ignorant and at times reprehensible behavior towards his subjects, thus defeating what should be the very purpose of the work. I do not know why, after repeatedly failing to use a proper attentive approach, he still refuses to understand the ethical dimensions of his photography, choosing instead to be impervious to the required responsibility assumed by an artist dealing with vulnerable human beings. It’s hard to shake the feeling that marginalized people and their conditions are more akin to a resource for him, extracting misery-porn wherever he sees a potential for it.

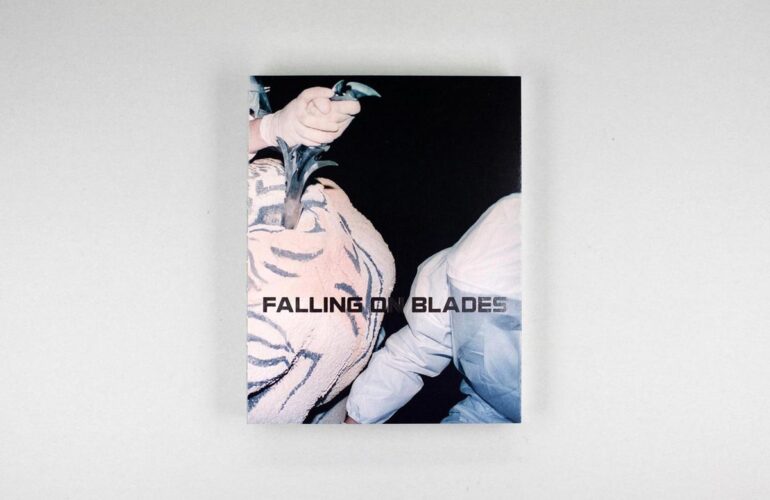

In early 2022 he launched an hour-long video promoting his latest book Falling on Blades. In it, he mish-mashes at some point excuses for his past behavior. He never formulates a clear apology though, nor gives signs of truly understanding what he did wrong, instead resorting to whataboutism and fact obfuscation typical for the post-truth era. Needless to say, it proved a thoroughly unconvincing affair, for the Romanian artistic community at least, as it remains unclear if his international audience is genuinely oblivious to the issues surrounding him or they just find them convenient to ignore. There’s no telling what he will prepare next, who he will manage to persuade to exhibit his photographs, if he’ll ever be able to meaningfully atone for his sins or, even more so, to understand them. It remains to be seen, but I suspect things will sooner take a turn for the worse than the better.

This article was published in Revista Arta issue #58-59, as part of the Scadalogy thematic dossier, coordinated by Valentina Iancu.

POSTED BY

Andrei Mateescu

Andrei Mateescu is an artist working with photography and an alumni of the Bucharest National University of Arts, holding a BFA and MFA after studying in the frame of the Photography and Dynamic Image...

andreimateescu.ro/

Comments are closed here.