One of the most consistent projects of last year was “The Ecologies of Care and Caring,” a program developed by the Nucleu 0000 Association, based on an interdisciplinary collaboration between artists, architects and professors and master students of the Faculty of Horticulture in Bucharest, which materialized in a succession of interconnected events: a series of exhibitions structured on the distinction between useful, poisonous, aphrodisiac and ritual plants in three galleries in Bucharest (Strata, Mobius and Leilei), two interventions by artists Beniamin Popescu and Miki Velciov in the Bucharest Botanical Garden, coupled with conferences, informative workshops and art walks curated by Gabriela Mateescu together with the researchers: Valentina Iancu (visual arts), Eliza Yokina (architecture), Prof. Dr. Mihaela Georgescu and head of works Lecturer Dr. Vasilica Luchian (botany).

Starting from questions derived from the homonyms of the word “care,” the cultural program “The Ecologies of Care and Caring” set out to explore the relationship between humans and the natural world in the contemporary context where, despite global connections through social networks and digital technology, we are trapped in an “accelerating social system of organized loneliness,” that is, according to The Care Manifesto (2020)[1], under the “reign of carelessness” towards all forms of life. The Care Collective, the manifesto’s authors, argue that care, traditionally associated with the private sphere and undervalued in economic terms, should be recognized as central to our lives as a transforming force based on the interconnectedness of people, nature, sustainability, and social justice.

ANDREEA MEDAR AND MĂLINA IONESCU, VIAE FERRAE 3, SOIL, WHEAT, RUBBER, ACRYLIC, 2023. PHOTO CREDIT: ANDREI MATEESCU.

So, how do we define nature? How do we view our relationship with the plant world? The project coordinators have given a special place to the “viewing” of nature, starting from the theory of “plant blindness” developed by biologists James Wandersee and Elisabeth Schussler, who have highlighted a disparity in the attention humans pay to animals compared to plants, which results in a lack of concern for the importance of plants in ecosystems, food, medicine, and many other aspects of life and has negative consequences for ecological awareness and environmental protection.

How plants influence our daily lives and, more importantly, what responsibility we have for their existence represent processes of care and caring that require mediation, as defined by Sean Cubitt in Eco Media (2005), as the only guarantee of a future in which “quality of life includes all qualities and all forms of life,” of a future global democracy whose chance of existence, as the hole in the ozone layer stretches from the northern to the southern hemisphere, requires resorting not only to technological but, increasingly, to biological means. As described by Cubitt, ecological thinking involves exploring the subject-object relations of the individual to the non-human world of nature, both from the perspective of what kind of object nature is and how we define ourselves as subjects in relation to it.

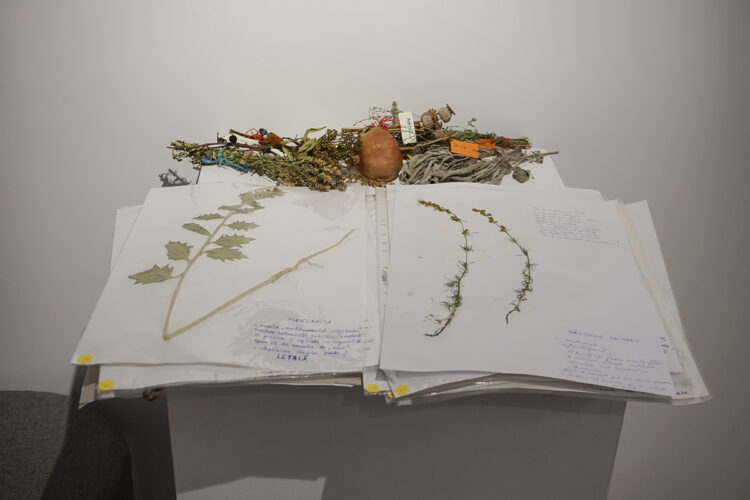

VIEW FROM THE “USEFUL PLANTS” exhibition AT STRATA GALLERY. PHOTO CREDIT: ANDREI MATEESCU.

The exhibition section dedicated to utilitarian plants (Strata Gallery, September 2-20, 2023) was inspired by the ways in which nature has been used, affected, and conceptualized as serving humanity. Plants have become resources, either cultivated sparingly in the traditional garden (found in the paintings of Horia Bernea or Hortensia Mi Kafchin) or, quite the opposite, poorly exploited, as in the work of the artist Miki Velciov: Hybrid (present in the gallery in the form of a video documenting the first intervention at the Young Naturalists’ Resort in Timișoara in 2021, but reconstructed on the meadow of the “Dimitrie Brândză” Botanical Garden in Bucharest), which questions the replacement of native species with new hybrid seeds, a process that increases short-term productivity but, in the long term, has devastating effects on soil quality and to the total disappearance of self-reproducing seeds.

MIKI VELCIOV, HYBRID, INSTALLATION IN THE BUCHAREST BOTANICAL GARDEN.

Wedged between stone and metal and cohabiting with us in urban spaces, as we see in Liliana Mercioiu-Popa’s interactive installation Vicinity: plants preserve their freedom and potential for infinite openings wherever they find a suitable place, like in the small compost bin on Ana Maria Micu’s balcony. The artist records a video documentation of an experiment that inspects apartment gardening in cramped spaces such as window sills or small balconies. The final result, where the plants grow in compost gathered from household waste, is captured in the painting: endless growth. … believing that hope can be dredged from ruin.

According to one of the most active contemporary naturalist philosophers, Michael Marder[2], life is characterized by cyclical, generational processes such as blossoming, decay, and regeneration. By deviating from this natural rhythm, mankind has created two narrative paths: the first involves the production of non-biodegradable materials, such as plastics and nuclear waste, which never decompose; the second aligns itself with utopian ideals of continuous progress and economic growth, ignoring natural cycles. We all (human beings and countless species of animals and plants, bacteria and other microorganisms, soil and atmosphere, climate, and ecosystems) experience this altered, “mutilated” narrative of the life of plants. Diana Miron’s audio artwork, The Island of Self, highlights the interconnectedness resulting from the coexistence of plants and humans. By recording plants with close-range microphones during the process of water absorption, the artist discovered rhythmic patterns and changes in sound when plants come into contact with humans.

The same Michael Marder explores the “Phoenix complex,”[3] highlighting humanity’s historical interpretation that nature’s cyclical regeneration is a guarantee of its infinite capacity to recover, thus granting itself permission to continue to harm the world, with the expectation that it will be reborn like the mythical Phoenix. This mentality is also reflected in the attitude we have towards our own bodies, expecting them to regenerate after various forms of trauma or exposure to harmful substances such as carcinogenic food additives, radioactive isotopes, and environmental pollution.

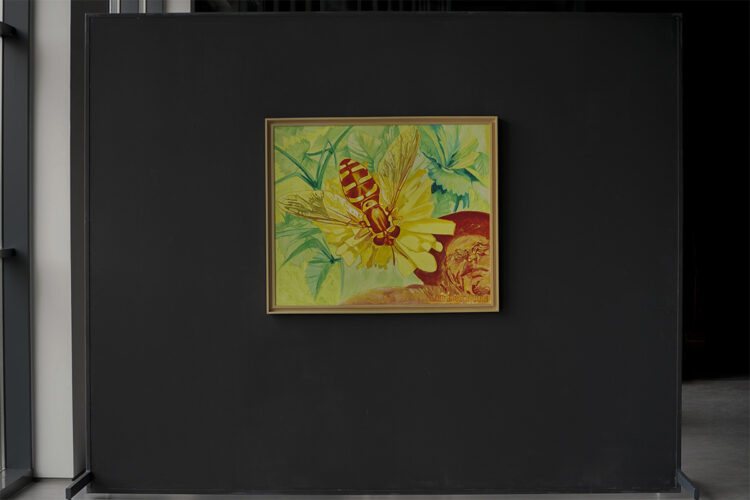

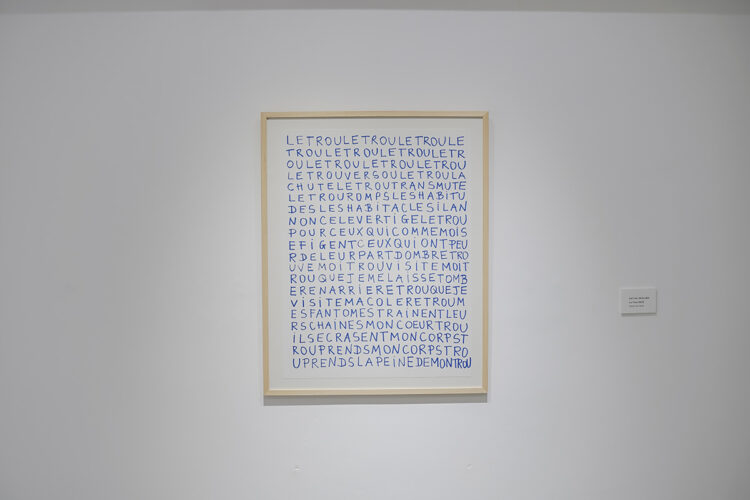

The exhibition focusing on poisonous plants (Mobius Gallery, 7-30 September, 2023) included projects presenting possible worlds in which fungi are the primordial elements of human existence, constantly metamorphosing and growing in a network of mycelium, as in The First of Us, Marina Oprea’s installation, post-apocalyptic worlds, without depth or horizon, where cacti remain among the last survivors, as in The Cactus at the End of the World, an intermedia collaboration between painting and VR by Iulian Bisericaru and Dragoș Dogioiu that gives access to the perspective of non-human life forms, or worlds that need to be discovered, composed, as in Katja Lee Eliad’s graphic poem Le Trou.

MARINA OPREA, THE FIRST OF US, DETAil. Photo credit: Andrei Mateescu.

In the section dedicated to ritual plants (Leilei Gallery, September 16–October 30, 2023), a special place was held by the belladonna (Atropa belladonna), explored visually by Diana Matilda Crișan and Marta Mattioli in soft, textile forms or, on the contrary, hard, metallic shapes, illustrating the ambivalent nature of this mythological plant whose properties have placed it at the center of magic, healing, murder, or seduction rituals. Other poisonous and, at the same time, healing plants such as the henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) and the jimsonweed (Datura stramonium often found in Bucharest’s wastelands), were brought to the exhibition by head of works Vasilica Luchian, responsible for the production of the herbariums and selecting the plants corresponding to each section.

VIEW FROM THE “RITUAL PLANTS” EXHIBITION HELD AT LEILEI GALLERY. Photo credit: Andrei Mateescu

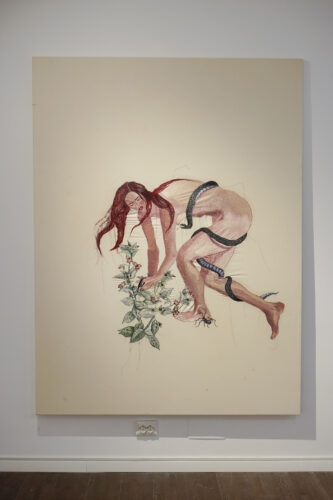

In the exhibition dedicated to aphrodisiac plants, Alina Marinescu’s papier-mâché sculptures, placed at ground level and almost lost through ivy (another plant with healing and poisonous attributes), were highlighted by red and ultraviolet lighting. The work shows various stages of love, from solitude and self-love to mutual and passionate love. Love was also represented in Livia Greaca’s sculptures budding from pressed textiles, which were set in contrast to Miron Schmückle’s visceral drawings that combine imaginary flowers with genital forms. On the same floor, Studies for Daphne by Ciprian Mureșan, the curator of the Romanian show at this year’s Venice Biennale, refers to bay laurel (Laurus nobilis), a plant that brings benefits when the leaves are used for tea or spice, but produces drowsiness and impairs cognitive functions if consumed in excess. The work draws on the legend of the nymph Daphne’s transformation into a laurel to escape the unwanted love of the god Apollo, a symbolic gesture by which woman-nature escapes from patriarchal domination.

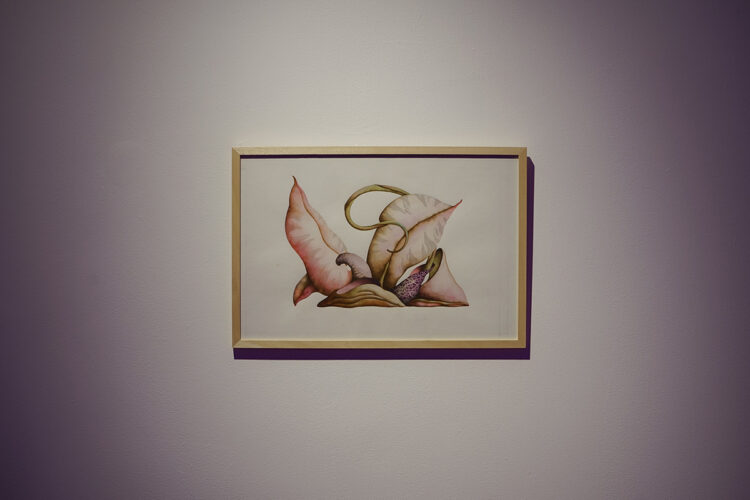

CIPRIAN MUREȘAN, DAPHNE, PENCIL ON PAPER. PHOTO CREDIT: ANDREI MATEESCU.

Each of the exhibitions included the perspective of botanical specialists, and one of the most comprehensive and informative was the research of Andrei Conțiu (a Master’s student at the Faculty of Horticulture in Bucharest, Biodiversity Conservation Management Master’s Program) from the section at Leilei Gallery.

By presenting the plant as a collection of symbiotic ecosystems, “The Ecologies of Care and Caring” highlighted the importance of interdependence and the need for mediation and solidarity between all forms of life. Designed in the context of care for nature and concern about contemporary ecocide, the project integrated contemporary art, architecture, and botanical research, offering a visual, poetic, and educational insight into the complexity of human and non-human communities sharing the same world.

[1] The Care Collective (2020) The Care Manifesto, Verso

[2] Michael Marder (2023) “A Philosophy of Stories Plants Tell,” Narrative Culture: Vol. 10: Iss. 2, Article 3

[3] Michael Marder (2023) The Phoenix Complex: A Philosophy of Nature The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England)

Translated by Camelia Diaconu

POSTED BY

Raluca Paraschiv

Raluca Mihaela PARASCHIV (Ionescu), artist, researcher, and lecturer at the National University of Arts in Bucharest. With a transversal professional background in the fields of visual practice and th...

Comments are closed here.