Some years have past since I first saw a work by Olivia Mihălțianu, a black&white video about a female character with the typical apparel of a 50s movie star that is nonchalantly strolling on an island. Back then, I didn’t fully understand what the artist was trying to say, although the refined role-play was clear to me, the distance-assuming and the costumes so that you don’t identify with her as a spectator. I revisited her works at Anca Poterașu’s, where the exhibition rooms, pretty unwelcoming for object installations, were for the first time fitted for the easily fetishistic display of portraits and emblematic objects from Olivia’s costumes.

Until now, I never really paid much thought to the personal route of a singular artist – especially an artist who is so obviously preoccupied with constructing her own character – being instead absorbed by macro work, meaning curatorial projects with political implications. Besides, my tendency is to to look for the political even in situations where it is very well hidden – I also told Olivia that what draw me to her ensemble of video works + the paraphernalia from the rest of the gallery was the fact that I perceived a certain coherence which, nowadays, is political. What I am trying to say is that an artistic route that has been patiently developed for 10 years cannot be neglected, no matter if the results are intermediary or even final. In a world that seems to be characterized by fragmentation, be it deliberate or intuitive, coherence is something almost anachronistic or, on the contrary, it is a position of resistance. Coherence also means the possibility of expanding certain themes both profoundly and extensively, which leads to connections with other areas that might be overlooked in the case of a guerrilla-style intervention, but also leads to a more profound understanding of the contemporary art system, which is as valid a point of inception as any other for understanding the world, so long as it is not mystified.

At a first glance, the project “Winyan Kipanpi Win” is a (more) complex stage in outlining the artistic ego, in which Olivia reuses gestures, costumes, objects and situations from past works in order to polish up a female persona that is characterized from the very start by sensuality, silence, elegance and detachment. We begin with the very name Winyan Kipanpi Win, given by the Sioux tribe to Queen Mary during her United States tour in 1926, which gives the artist the possibility of working with a series of symbols of femininity and power. The 2008 “Island” is the first piece of this puzzle, where the artist seems to play the role of an actress caught in a moment of relaxation. Just like in that first video, the character from the series of works that comprise the new exhibition is not only detached, it is also fetishized so that any identification is impossible. One becomes subtly aware that this is as much a deconstruction as is a construction, although the two operations do not necessarily target the same object. As much as an increasingly sophisticated female character is built, so is its context deconstructed until it becomes abstract, absurd even. And whether it is the cinema start, the queen or the artist, the context in question is always the mythical public space of a selected few, the beautiful, the talented and the privileged.

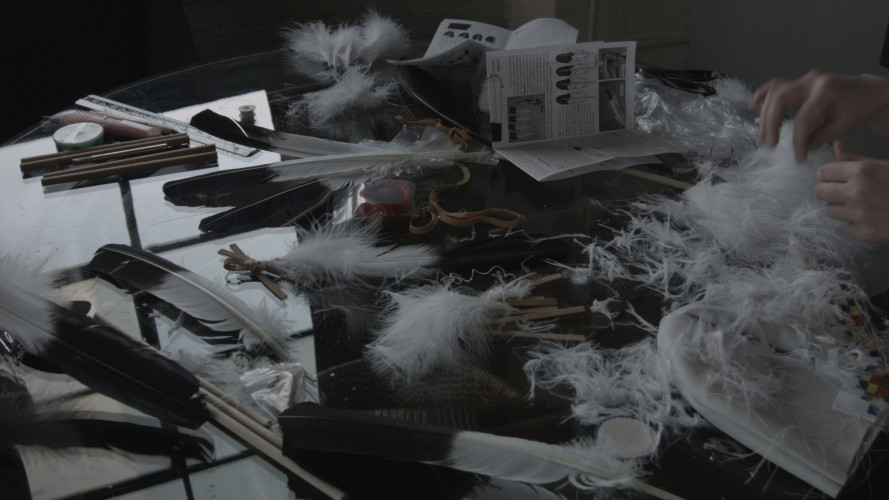

“Winyan Kipanpi Win” is the first project that brings the dimension of making of in the artist’s works, determined by the context of two residencies, one in Krems and the other in Cleveland. The first dimension is the obvious – yet deceiving – parallel between the artist and queen: obvious due to the repetition of gestures and royal symbols performed by the artist, deceiving because artists are an aristocracy in an illusory manner. The video is made up of long sequences, allowing the viewer to detect the relationships between the protagonists, to make out the outline of the frame and to even evaluate the connection between the artist and the object of the film. In the Krems work, the scenes with rituals conducted by the artist playing the role of a queen that is traveling on a luxurious ship who is awaited by the town’s people in the port are constantly repeated, leaving room for a deliberately embarrassing error. In the piece produced in Cleveland, the scenes in which the artist works on her Sioux royal crown are framed by long scenes of daily activities during the residency: an auction in the host building’s engraving workshop and a series of scenes with students visiting the local factory. So the frame itself holds nothing glamorous, on the contrary, it highlights art as a process of work, research, promoting and self-promoting, buying and selling. Therefore the spectator cannot conclude that the artist is a contemporary aristocrat – quite the opposite, all the tricks pulled by young or active artists in order to be recognized and/or paid for their works are more likely to induce a sense of unease and pity.

In addition to this, Olivia also pays attention to the process and requirements of the residency as a typical situation of artistic production. The condition of the two residencies was the social involvement of the artist, be it the so-called activation of the Krems inhabitants, or the activities organized with Cleveland students. This is such an ordinary thing in the art world that people don’t even mention it anymore, the artists write the application forms detailing an “essential” social project, and the people who live near art centers see themselves engaged in all sorts of abstract actions that rarely last or are beneficial in any way. In this regard, artists going through residencies reminds one of the official visits by long-ago queens: a lot of gestures loaded with symbols of power that disappear once the main character has left.

It is in this heavy artistic context, an industrial-declined-reconverted context dominated by superficial social policies, that Olivia manages to regain the meaning of the gestures that construct her own character, gestures that are developed either in the intimacy of the workshop or in front of the camera. So we come back to the initial intuition, that this might be some sort of self-portrait. But it has become clear whose portrait this is: not just of a woman, but of a contemporary artist, a special kind of breed, a fetishistic creature, a phantom image that hides numerous self restrains. The parallel artist/queen is not so much a flattering route, as is a source of frustration – but a frustration that is overcome with a certain feminine grace. Far from leaving you depressed and powerless, as it often happens when you attend contemporary art events that claim to be political, this art show reveals the self-referential and consistent artistic act’s potential to resist, it illustrates the determination of making art using a canon of professionalism, without trying to become something you’re not.

Olivia Mihălțianu, „Winyan Kipanpi Win”, curated by Anca-Verona Mihuleț, was at Anca Poterașu gallery.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

1 Comment

An excellent article about Olivia’s work !

Magda Carneci