In this traumatic period of insecurity and unbridled mass-media affects, when the COVID 19 pandemic is causing the gradual dissolution of natural communication, the art scene is struggling to survive, to participate in the all-so-necessary process of mediation, of debating current and at the same time painful topics. In this difficult context, the exhibition Wounded Identity proved timely, both as a chance to reinvigorate an art scene anesthetized by the pandemic and as a chance to reflect on the way in which we look at, recognize, and (re)construct ourselves.

Launched by the experienced curator Ileana Pintilie, this relevant project of identity questioning in the age of post prefixes (postmodernity, postfeminism, posthumanism) has brought together various media and approaches from cultural centers like Bucharest, Cluj, and Timișoara under the umbrella of a critique directed both at the limitations of a society based on uniformization and consumption, as well as at discrimination (assaulting, wounding, infecting, attacking) based on gender, sexual orientation, or peripheral position. The pandemic added a new layer to the problems anticipated by the curator and artists – such as their lack of freedom and power as actors in a scene dominated by institutional power centers and financial schemes, the intrusion of technology in the sphere of identity and authenticity (of the self, of art) – a layer marked by the replacement of touch and physical communication with interaction at a distance and the assimilation of masks into the pattern of the human face.

As a result, the probing of identity was related both to the theme of the body (be it the docile body, after Foucault’s model, Deleuze’s body without organs, or the sick/quarantined/hermetically sealed inside a zipper bag, as with the current pandemic) and with the types of media involved in the process of analyzing and laying bare identity through art. From her position as a reputed critic and art historian, Ileana Pintilie raised relevant questions like: what do the notions of portrait, self-portrait, and action presuppose today? How does the relation between identity and authenticity evolve in the age of mechanical/technological reproduction? Her investigation also questioned how art can still function cathartically for underprivileged genders, subcultures, and communities, in a post-performance age, in which the artist often forgoes their actual presence, retreating into a representation.

Among the exhibition’s five intermedia approaches, it is Pusha Petrov’s that most explicitly tackles the issue of subcultures. In my opinion, her works in the Bucharest exhibition continue and deepen her artistic research, marked by eroticism, pop culture, and camp sensibility (see her series of pink handbags, slightly opened, seen from above, reminiscent of an open flower or the female sex organ, Marsupium à main, Art Encounters, 2017), adding anthropological, ethnological, ontological (finitude, time) layers.

Her works exhibited in Bucharest are part of a broader artistic research carried out in Paris in African hair salons around the Gare de l’Est with the aim of exploring the ways in which hair can be a medium of artistic expression. The series of large-scale photographic portraits of African braids, titled (des)coase / (un)stitch, 2019, reveal hair as language, artistic medium, mark, taboo. The erotic connotations of women’s hair in oriental cultures are thus unconcealed: its status as an almost living, almost sacred thing that needs to be hidden, tied, bound, its capacity to simultaneously fascinate and frighten, to encompass a power relation similar to that of a religious object.

For Pusha Petrov, herself part of an ethnic minority of Bulgarians living in Banat, the project’s center of gravity resides in its participative side, in her visits to the hair salons in Paris, where they often attach extensions, and in her conversations with the members of the community. After the artist’s hair had been braided and transformed into an organic architecture by the African artists, Pusha Petrov initiated a new collaborative performance, a series of interventions with colored thread in her new hair structure undertaken by her and other artists. We see how the action of stitching hair, with thread of different colors than black, the one often used to conceal the act of production, as well as that of sewing together, everyone with their own laws, but in the context of the same communication platform, can be interpreted as subtle comments on de-construction as an artistic method and the way in which our identity is constructed in the mirror (see Lacan) and in the world (relative to a certain community, history, values).

This intermedia project, situated at the intersection of photography with performance and body art, is complemented by the sound installation Chignon Chouchou (2019), a series of buns braided in the same style that speak (with the help of internal speakers) about urban myths built around hair. The two projects are both a relevant commentary on the dissolution of specific art genres and languages, as well as an existential discourse built around the contested dichotomies between to be and to seem (here hair extensions oscillate between the status of mere appearance and that of a line of flight towards the vast territory of the transhuman), between the two interpretations of woman: woman as natural object and beautiful appearance (plant-like beauty lacking spirit) and woman as artwork, as essence and free spirit able to modify her appearance.

In the line traced by John Dewey’s pragmatist aesthetics (Art as Experience), recently taken up again by Richard Shusterman, Pusha Petrov’s research in the African salons confirms the fact that doing one’s hair is both an authentic episode of daily life and an aesthetic experience capable of bringing together a community (be it just for one afternoon in a modest room with work chairs and curtains). In this context, art practice becomes charged with existential value. It becomes a chance to debate and promote a set of (alternative) values and beliefs capable of outlining the basis for an existence and an identity based on belonging to that particular subculture.

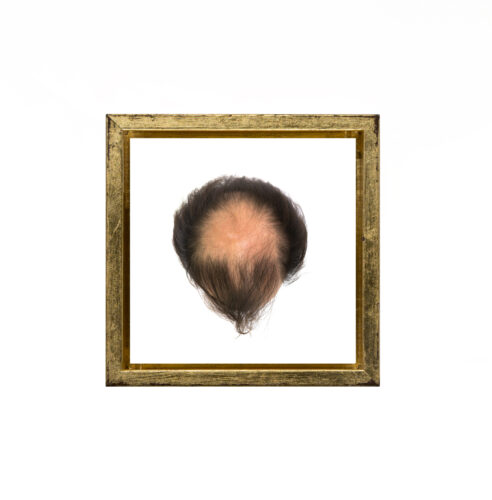

A third work, l’image qu’on a jamais, works by the principle of surprise, the unexpected angle, or the kind of deformation seen in mannerist painting or expressionist film. What at first seems like a series of portraits without features or mysterious maps reveals itself to be representations of hairless heads seen from above, a series of alopecial configurations. The universal character of these faceless faces, capable of revealing human finitude marked by every moment that, one after another, becomes past, by Bergsonian duration, is augmented by the valuable technique of digigraphy and by the golden frames.

A precious commentary on finitude is also offered by artist Olivia Mihălțianu in her project Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio (2020). The title reveals a reinterpretation of the famous La noyade (1840), the self-portrait manifesto of Hippolyte Bayard, who lost the status of inventor of photography to the famous scientist Daguerre, supported by the French Academy. In an original attempt to bring together the problem of identity and finitude, of the artist’s condition and how technology influences art practice, Olivia Mihălțianu picks up the message of Bayard, who, thanks to his paradoxical self-portrait as a drowned man, succeeds in defying the vagaries of fate and the limitations of technology (shooting a portrait back then required the subject’s immobility and the closing of the eyes), stubbornly remaining in art history, even if as the founder of staged photography.

Combining an exciting synthesis of media (photography, video, sculpture) with some of her favorite topics, like the self-portrait and roleplaying (starting with the exhibition Femidon, Galeria Nouă, 2007), the fragile relation between nature and technology (see her interventions in nature at the Tranzit garden or her contributions to exhibitions at DPlatform, 2018), Olivia Mihălțianu delivers a mature commentary that relates the portrait to technology, positions photo-video practice on the fine line between aesthetics and technology. In other words, the image produced with a camera, often dismissed as mere mimesis, a recording of reality, reveals in this context its capacities as a magic, spiritual tool (Robert Bresson) that can capture the beautiful, the aura, identity. The beauty of the technique, of the camera and its working methodology, based on chemicals, errors, and achievements, complements natural beauty.

The installation Self Portrait as a Drowned Artist and The Portrait Studio, in my opinion the strongest presence in the show, is remarkable in that it outlines a space within space, delimiting an independent slice of space-time. In other words, the artist constructs, in one of the gallery’s rooms, a replica of her studio in Sofia, in which, together with sculptor Stoyan Dechev, she devoted herself to the intermedial recording of the human body and identity, relative to perspective and lighting. Her subtle understanding of space defines Mihălţianu, who studied photography and video, as a transmedia artist, simultaneously illustrating the difference between mere photographer (in Vilem Flusser’s terms, the mere functionary of their apparatus) and the artist working with photography (film), probing the limits of the technical image and its interference with traditional practice (portrait, landscape).

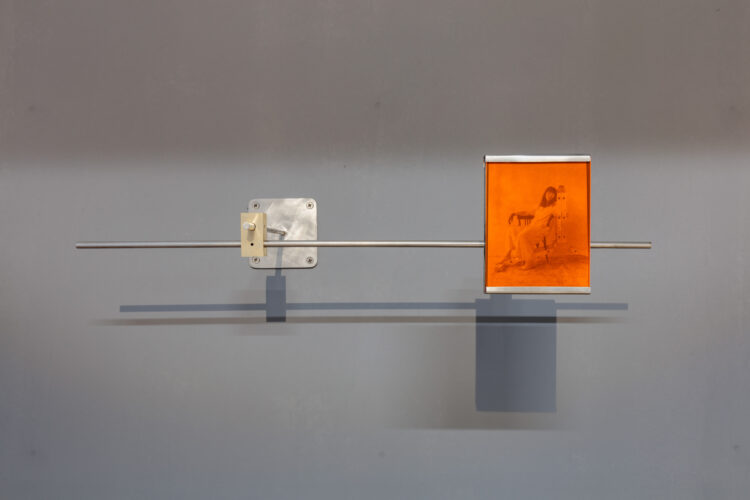

The space is organized into four cells, of which the first two seem to be dedicated to the beautiful image favoring contemplation, bringing once more into discussion Mihălțianu’s previous studies on nature, but also her sensitive cyanotypes, some of which were made in performative-participative contexts (the old cyanotype technique was practiced by Bayard himself). In the first cell, in order to evoke the fragile status of the contemporary artist, but also photography’s relation to the limitation of the body, Olivia Mihălțianu juxtaposes a sensitive and precious salt-based print, which restages the posture of the drowned man deep in healing sleep, with a series of metal rods reminiscent of the structures used in the early days of photography to immobilize the subject. The beautiful orange photograph awakens multiple connotations, from the image of Ophelia floating on the water, calm, unmoving, and the sepia blitheness of post-mortem photographs, to the redefinition of contemplation (as the assumed solution of temporarily taking refuge in dreams, in soothing beauty) and the revelation of the principle of old photography, in which the price of the immortality afforded by representation was paid through a long exercise of bodily immobility before the camera. The second cell is dominated by a video in which images from the artist’s studio in Sofia meet images from the garden of the campus housing it, including an abandoned female bust on which rain and vegetation have left their mark.

If the first cells impressed the viewer through Apollonian beauty and invited to contemplation, the final cells are defined as a Dionysian territory of action: the shattering of the dream, the recontextualization of Bayard’s protest on an art scene dominated by institutions and market value. And so, the third room, empty and flooded with a red light that gives the space an affective dimension, combines the features of a photo lab, in which development may impose a temporary suspension of our dominant sense of sight, with the tension of the erotic, transgressive act, with a bringing to life (as painful as it might be). The final room represents a photo studio recontextualized in the selfie age, in which more and more people choose to create their portraits themselves. Here the audience is invited to use the necessary props (a support and lighting that many have already set up at home for online interactions during the pandemic) to take selfies with their own phones.

Immersive and interactive, the project offers a captivating commentary on the evolution of the technical image, from the first attempts to fix a representation in a photograph to the products of the digital age, the famous selfies, staged and prefabricated, created to be manipulated and distributed en masse. At the same time, art practice is defined as a painful and transgressive act, placed at the intersection of unlimited inspiration and imagination with finitude and humanity’s tragic condition.

One step further down the path of transgression is Adriana Jebeleanu, an artist who in 2012 chose to exit the art scene – and life, too. The story of this wounded and nullified identity is presented by exploring the register of the tragic, the strange, the unformed, and the sublime in a series of works with affective notes based on the contrast between noncolors (white, black) and a strong red. The transmedial character of these actions, which are, photographed, filmed, or performed in front of an audience, combines with an anti-art orientation, revealing an acute crisis of representation felt by the artist, who had a background in painting. One example in this sense, Blind, Deaf, Mute (2011), in which the artist sits in front of a piano without touching its keys, a (white, red, black) hood over her head, is a reinterpretation of John Cage’s famous 4’33’’.

The impossibility of communication makes Jebeleanu waver between the romantic solution of retreating from the world, of projecting disconnected dream realities, and becoming involved in cathartic actions that represent both a means of protest and an attempt to escape the self towards the other. Towards this purpose, the dream state, the trace, and absence alternate with presence – the more silent and abstract, the more disquieting.

The register of retreat is illustrated both by the performance Blind, Deaf, Mute and by short videos like I will forget, 2009, built around the dichotomies of appearance-presence, clothing-body, body-spirit. If in the first case the solution seems to be probing one’s deep interiority (one’s fears, desires, drives) in search of the last traces of authenticity, in the second case a series of white garments hung in the forest reveal the lack of a body, the artist returning to a still-free nature, to the model of spontaneous creation. The action’s register is implied when the artist decides to look the viewer in the eye, directly in the context of a performance or mediated through a video like FAST FOOD, 2008, a protest against the lack of authenticity and the machinic rhythm of life, in which the artist, dressed in white, eats the petals of a lily. Even in the video version, her piercing gaze goes beyond the optic level and into the haptic, the gaze that touches, that unsettles the audience, driving them to action.

Videos like Totally Love (2011), in which a blood-like liquid overflows from a cup, invoke the link between authenticity and angst, the act of self-abandonment, the act of flowing out of the body, the painful outlines severing us from the other now melting, an act that becomes possible (as Georges Bataille warns) only in eroticism or death. Overcoming the world of conformism, of identity void, the mechanization of life, the conventionalization of art determines the artist’s engagement in a transgressive project of probing the limits of human psychology, of the frontiers of knowledge, bringing back into discussion Susan Sontag’s definition of the modern artist as a broker in madness. In this sense, we must accept that art practice that has a cathartic aim, the performative act taken to its end, overstepping physical, corporeal limits, recovers the site of the sacred, but also proves risky for the artist as a person. In Adriana Jebeleanu’s case, the price paid for ultimate authenticity, for the experience of self-abandonment, for the acute experience of the limit, which, in Bataille’s opinion, seeks “the approval of life unto death,” was passing away.

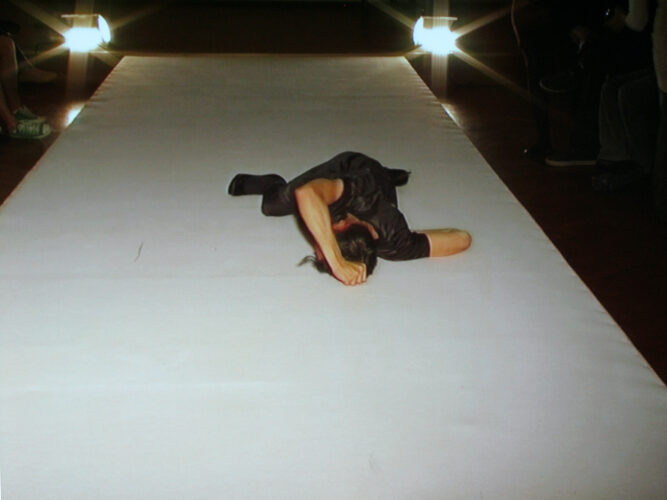

Cluj-based artist Alex Mirutziu showcases a similar process, on the same trajectory of finitude and transgression. In his two works exhibited in Bucharest, he tests the limits of the body, gender identity, and sexual orientation. In Feeding the horses of all heroes, 2010, a performance recorded at the Accademia di Romania in Rome, a conservative, institution, the artist engages in a cathartic exercise of fall and recovery. Crossdressing as a model, a predefined object of admiration, and armed with the proper attire (high heels, provocative clothing, absent, inscrutable gaze), he traverses a catwalk under the audience’s attentive gaze. Even though, for a short time, he seems to conform to the identity of a celebrity specialized in apparent living, Mirutziu breaks the rhythmic walk through an unexpected fall (with the sound of a dramatic, dissonant metallic sound), which then repeats rhythmically. This ritual of falling (the existential coordinate philosophers associate with the loss of the authentic self in favor of impersonal qualities: what people say, think, wear) seems to invoke not just the artist’s condition and the fashion industry, but the entire society of the spectacle (Guy Debord) in which we find ourselves today hooked up as devices, docile bodies, organs, anesthetized and isolated spectators, premanufactured identities.

The contrast between fall and recovery brings into discussion Mirutziu’s research on the struggle of writer Iris Murdoch with memory loss and Alzheimer’s, confirming the artist’s ability to unconceal human finitude, the limits of the body, the will, language, endurance, of recovering the beauty and heroism that are inevitably concealed in error, in human frailty. This same contrast reveals a new kind of tension, the human being’s tension between verticality and horizontality. In this sense, Mirutziu adheres, like Baitaille and Rosalind Kraus, to an aesthetics of the unformed, of basic materialism, an aesthetics of recovering the body and its fluids. Its goal is to overcome idealism and prudishness, to become horizontal, accept the fact that even though our heads point to the sky, our link to the earth, to the horizontal, remains essential.

The same revelation of modern humans’ infatuation with having surpassed the animal stage, the biological mouth-anus axis – having emancipated themselves from the horizontal – also animates the portrait Doings for a Living (2018). The image functions after the model of Deleuze’s gros plan, laid bare in his books on cinema (Cinema I, the affect image), replacing psychological representation with bringing affects themselves forth into presence (with the help of portrayed features): sadness, fear, desire, boredom. In this case we are confronted with a close-up of a mouth: a battleground (see the Nike mouthguard that boxers wear for protection), an orifice associated with poetic declamation, with the noble act of speech, with expressing concepts and thoughts, and also an emblem of the biological acts of screaming, vomiting, and spitting. In this sense, Mirutziu’s works perfectly illustrate Bataille’s theory on the world’s duality, on the double connotation of the sacred (Lat. sacer) which simultaneously signifies sainthood and the accursed, the act of killing.

Adelina Ivan stands out in the context of a series of recent (2020) minimalist actions that enter into a relevant dialogue with Pusha Petrov’s commentary on hair and femininity and with the other artists’ analyses of bodies and finitude. In the curator’s opinion, these actions fit into a category of post-performance: distant, recorded, performed for the eye of the camera, a performance in which the artist is an abstract part.

In Hello Vera, an investigation into fragile femininity, imperfect when compared to the invincible models in advertisements, the artist looks at herself in the mirror combing her hair. Her rhythmic gestures bring up both women’s status as erotic object as well as the extensive mechanization of daily life and the prefabrication of identity. Her approach does not engage an affective, expressionist register, but rather a conceptual one at the intersection between poetry and theorem (see Pasolini’s films and Georges Perec’s poetic investigations into space). The body in turn becomes a concept, a virtual construct. Brushing hair, lying down and getting up from the bed, tracing lines on the wall, these actions are transformed one by one into artistic geometries that function by the principle of repetition, into ritualistic gestures of exorcising matter, the visceral, of dispelling the tensions of an insecure and alienated world.

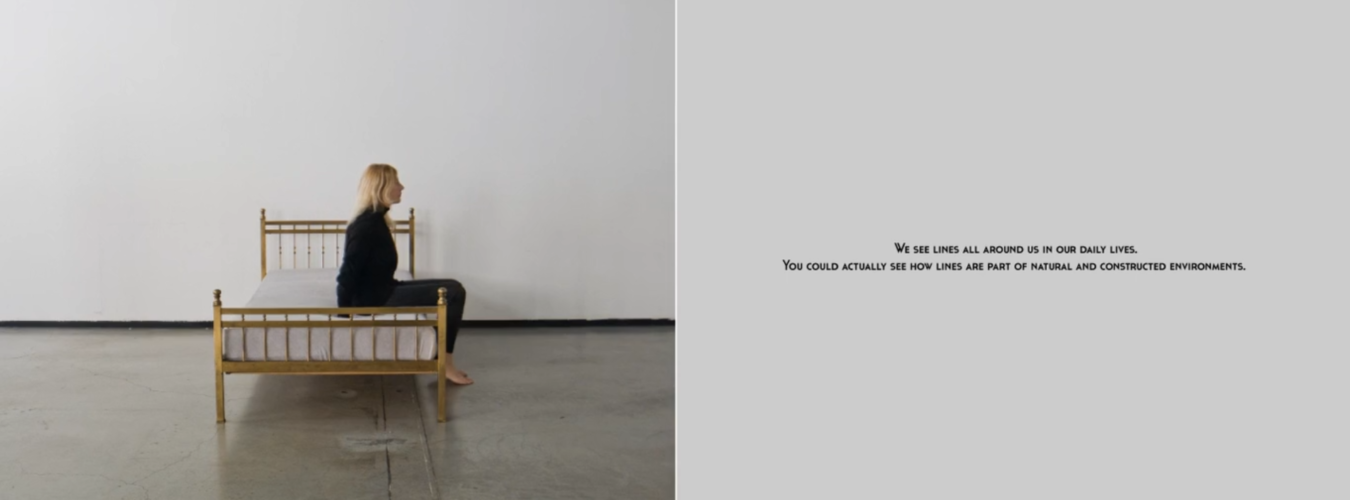

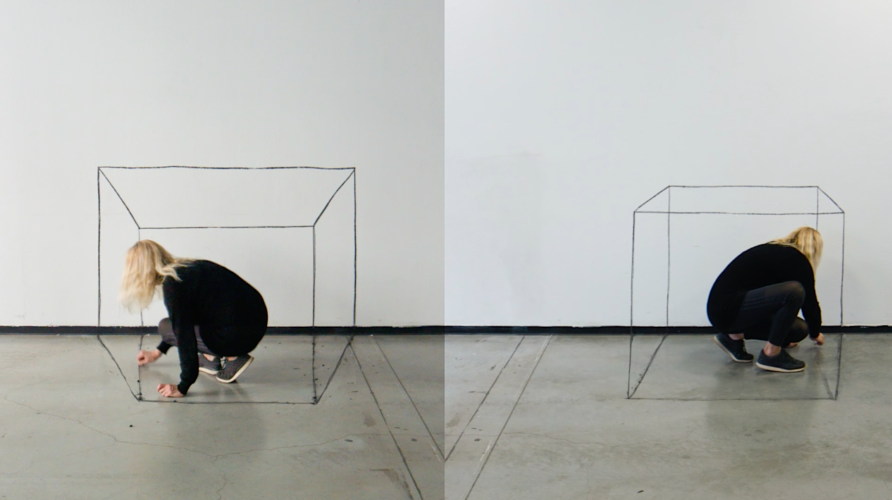

Left square, right square shows the confinement of the artist’s body into two rectangular structures. The doubling is only apparently symmetrical, as the body manages to escape from the geometric outline in just one of the two windows. The situation is reminiscent of Bruce Nauman’s projects from the 1970s, in which the representation of the body was drastically affected by an abnormal perception of space, like the alienating installation Green Light Corridor, which asked you to cross a straight, narrow, and uncomfortable space lit by an aggressive green neon light. A critique of the capitalization and mathematization of space, of reducing its natural forms (irregular, circular) to the straight line, is continued in Circling, a ritualistic performance in which the artist sits down and then turns on a bed. The image is accompanied by a second window with commentary texts around space and the language of lines (straight, circular, organic). The obstinate representation of the bed reiterates Perec’s poetic comments on affective space in Species of Spaces: “The bed is thus the individual space par excellence, the elementary space of the body.”

This is how art unconceals an interpretation of the contemporary individual’s painful isolation within the rectangular perimeter of the bed, the room, the home, and the city. If we are bodies, and our bodies cannot be separated from the world through the simple gesture of division (the inside separated by the skin from an outside), if, on the contrary, our bodies represent the extent to which we can move, know, and touch, then any act of separation/isolation represents an amputation of the body. In this sense, the project curated by Ileana Pintilie represents a phenomenological exercise that confirms, in the alternative language of the image, that being means nothing outside of being in the world, that humans cannot exist without their bodies, whose (pandemic) isolation is tightly linked with the marring of identity.

The exhibition Wounded Identity, curated by Ileana Pintilie, took place at Anca Poterașu Gallery, Bucharest, during November–December 2020.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Oancea

Raluca Oancea (Nestor), member of International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS), is a lecturer at The National University of Arts in Buchares...

www.Dplatform.ro

Comments are closed here.