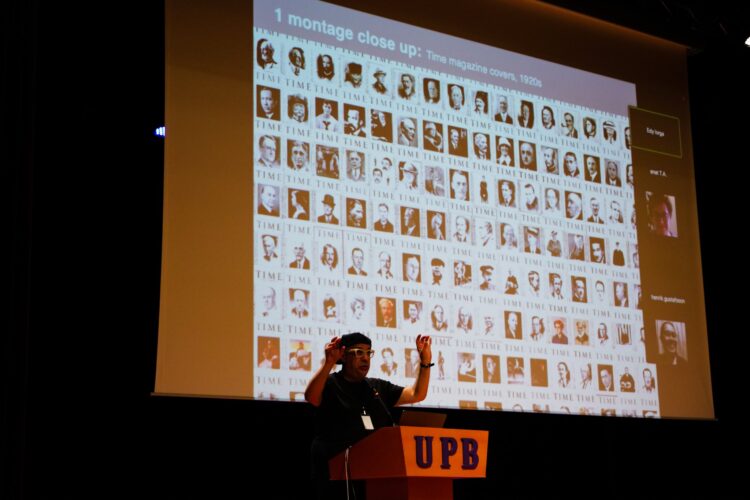

Between the 22nd and 26th of June 2022, the largest cinema and media studies conference in Europe took place in Bucharest. A reunion of the main academic network of this field, the European Network for Cinema and Media Studies (NECS) brought hundreds of researchers from all over the world, but especially affiliates of European universities, within Politehnica University. The event was organized by the University of Theater and Film, together with numerous partners: the Excellence Center in Image Studies (CESI), the Babeș-Bolyai University, the Sapientia University, the Goethe-Institut, and the French Institute in Bucharest. The researchers’ presentations revolved around the topic Epistemic Media: Atlas, Archive, Network, with 109 total panels, often 10 taking place at the same time. A wide variety of topics were approached, from using archive materials about interwar Europe or colonial Indonesia, to tracking devices, to Russian montage theory, to NFTs, from Alexander Kluge to Apichatpong Weerasethakul, from map to surface. The content of such an event would be impossible to map out from a single perspective. Any attempt at synthesis will always overlook important elements and will be accompanied by a rush between conference rooms and badge colors, from one lecture to the next. Besides the panels, each day was celebrated with a keynote in the UPB’s spacious aula magna: Stefanos Levidis from Forensic Architecture, Georges Didi-Huberman, Sybille Krämer, and Lev Manovich. The final day was hosted at Cinemateca Eforie, where a selection of science films produced by Sahia Studios were shown. These were followed by the film Pays barbare (2013) by Yervant Gianikian & Angela Ricci Lucchi and a discussion around it, broaching the topics of historical memory and archival practice, between directors Sousana de Sousa Dias and Radu Jude. Christian Ferencz-Flatz, who I had the pleasure of interviewing bellow, led the event’s organizing team, whose members included Andreea Mihalcea, Andrei Rus, Gabriela Suciu, and Irina Trocan from UNATC, as well as Andrea Virginas from Sapientia University in Cluj-Napoca.

Given the point in time when the discussion took place, some of the references may already seem outdated, given the current situation which began developing just a few months later, but this in fact augments some of the ideas expressed below. The theme proposed for the 2023 NECS colloquium, which will take place between 13 and 17 June in Oslo, is Care.

To what extent do you think that the format of such a huge conference fulfils its epistemic function, instead of being just a networking opportunity?

I think the networking function is not to be ignored. Of course, the concept has a bad reputation in the academic world because it is associated with a form of careerism, with the figure of an individual climbing the ladder through their connections, instead of through their achievements in terms of research, publications, etc. It’s more of a clique concept suggesting an illegitimate career, and of course, this meaning of networking exists as well. But there is also a meaning that’s more important to academic life, connected to extra-institutional networks, which are vital in the life of academic fields; they partly help make sure that the collaborations between specialists and institutions in a given domain work out and also ensure an ongoing form of communication between working groups. This helps make research results visible for people interested in said field. This whole thing is important for research networks and how scientific disciplines work nowadays, and I think it is especially important for NECS, which defines itself as a network from the get-go. Moreover, the notion of network pertains to the general theme of this colloquium, which was called Epistemic Media: Atlas, Archive, Network. That network had an ambiguous meaning: it referred to technologies of connectivity, to how the internet and new platforms influence our epistemic activities, but also to human networks, networks of researchers, and how these social institutions determine our research activities. And, of course, the former influences the latter, which looked different before the advent of the internet. But what I mean by all of this is that from an epistemic perspective networking is not only more interesting than it looks, but also that, this year, it itself became part of the theme being discussed.

How much of a shift in focus within media studies have you noticed from one year to the next? In how far can such an event keep up?

It’s hard to gauge how measure such an event is of producing mutations within a field. It responds rather to transformations within the field. These are perhaps less visible in Romania, where film and media studies have been a relatively small presence in academia, which is of course related to many factors, like their development, in all socialist countries, within “vocational” universities, places for the practical training of workers in the field of film. Meanwhile, if you look at the field’s development in the West, it has broadened its scope a number of times. At first, it was, roughly put, focused on auteurian analyses of capital-C Cinema, aesthetic studies of cinema as an art form. Later, this was complemented by studies of mass industries, radio and television, and many professional groups changed their names to things like film & television studies, radio studies, etc., up to what we now call media studies. The situation that the present colloquium tried to address is that these last few decades have seen the proliferation of all kinds of uses of film that, broadly, have nothing to do either with aesthetics or with entertainment. Researchers speak in this sense of utilitarian films, such as educational, industrial, but also scientific ones (as well as others), which have long been a niche topic – they are therefore often archived in inadequate conditions or even not stored at all, which is why some of these productions were dubbed “orphan films.” What’s certain is that what had previously been a marginal form of film that sparked no interest, the situation balanced out gradually, given that many professional – and not only professional – activities in contemporary society produce and use filmic images in one way or another. From CCTV to scientific research, from medical practice to the military industry etc., we have a mass of video productions that is no longer marginal by any means, but is instead prevalent within society. Media researchers have recently discovered that this is a relevant object of study, that they have something relevant to say about these materials, or, more precisely, that these materials have something relevant to tell us about media, about what film is, for instance. And it’s indeed true, we are no longer dealing with a marginal topic, as educational or science films, but with materials that are literally everywhere, and, if viewed to scale, we should conclude that cinema itself is rather a minor, marginal topic when it comes to defining film in general. And it is in this context that the epistemic use of these media plays a very important role. This is the line we tried to follow with this colloquium. Of course, there are specific problems here, as, if you think of medical imagery, a media scholar will produce a completely different judgment about what an x-ray is than a radiologist. There is a way of reading images that is internal to the scientific practices we are discussing here and a way that pertains to media specialists or visual culture specialists more broadly. The latter try to produce a series of transversal, parallel readings of the objects in question, to analyze them as material practices within a history of such images and within a history of visual practices utilized for scientific purposes; they try to offer a broader perspective in which to explain how media in general function rather than their immediate use within those scientific practices. There is a whole host of research topics that have begun to open up more acutely within the last 10-15 years, and the present colloquium comes to draw a line behind these efforts. To answer your question: of course, the colloquium’s theme isn’t new, we didn’t impose it, it has already been discussed at various levels in smaller colloquia, but our attempt to bring together people interested in this topic and to give this research a level of visibility that could not be achieved by the smaller, specialized colloquia that have already taken place is still relevant. We will be able to see the results of this attempt in the coming years. Results are not visible during the event itself, at q & a sessions, instead often manifesting afterwards, thanks to the contacts established here, thanks to the fact that people working within one sector of this discipline become acquainted with what is happening in a different one, leading to collaborations etc. Such gains are hard to quantify in the immediate posterity of such an event.

It feels that, in the last few years, there have been certain new ideas coming up more than some older ones. That new names are being mentioned. What such situations have you noticed at the congress? Lately, in the last year even, computer graphics, video, and media more generally have achieved a surprising level of technical finesse. Memes have become more refined, as have all the new graphic configurations and inserts that we see on social media or various websites. On this level, you can feel a recent fault line between present and past.

A whole array of topics has been establishing itself these last few years and the pandemic has, of course, brought them to the forefront. 2021 saw the publication of an open-access book titled Pandemic Media, which looked at how media have been present in our everyday private and professional lives during the pandemic, following research into utilitarian film and the reception of vernacular visual practices. Beyond Zoom, which was obvious, the work analyzes an entire series of apps and media augmentations in detail. Generally, this is a topic that has gained much importance during the pandemic, and this has highlighted the way in which media infuse inapparent processes in our life and how they transform it. What I would also note about the congress’s relevant themes would be perhaps – and this was a surprising thing for me – how little the topic of artificial intelligence was present among the papers proposed. I would have also expected Lev Manovici to talk more about aesthetics in connection with artificial intelligence, which was the topic of his last books. And this lack seems to me all the more surprising given how prevalent the topic has been in more private contexts, in discussions and debates among participants about the colloquium. This is also, perhaps, an effect of the gap between when the call was published and when the conference took place, because during the many months between applying and presenting, certain themes come to gain increased importance, become a larger part of the discourse. This was certainly felt in last year’s edition, when, because of the pandemic, the congress was organized one year later, in Palermo, and the theme remained migration, transport, and borders – hot topics when the colloquium was announced, in 2019, while in the meantime, as we were going through a pandemic, in 2021, the focus of the discussions had shifted. Of course, things aren’t always so acute, but I think such a delay does interfere with our attempts to really gauge the discipline starting from such events. For instance, within those six months before the colloquium, new platforms such as DALL·E started to become popular, while they hadn’t been at the start of the year, having had only a small number of users, and conversations around AI-generated images practically exploded as the year went on, while until that point the discourse was focused rather on artworks employing such techniques (from Hito Steyerl, for example). Nowadays, many of these technical advancements are open-access, in a form that didn’t exist in 2021, so that any self-respecting media scholar today has first-hand experience interacting with these materials, which they might not have had before the congress. And I tend to think that such things change the disciplinary landscape a little, even during the time it takes to organize such an event, leading to shifts in the conversation from its initial proposals.

Having taken part in the panels, two names came up again and again, which have become almost canonical: Aby Warburg and Harun Farocki.

Farocki and Warburg’s presence is not surprising, and was predicted already in the conference’s call. The concept of atlas in the conference’s theme is of course a reference of Warburg, and it is in this same Warburg vein that my colleagues involved in the colloquium’s organization and I invited Georges Didi-Huberman, who tackled two of the topics announced in the title: the atlas’s relation to the archive. In his keynote lecture, Didi-Huberman spoke about Warburg’s way of working with images in his Mnemosyne Atlas, and about his own way of working with images as an art historian, which, according to him, articulates alongside the word-based theoretical discourse a parallel form of discourse operating through images. Warburg is therefore the precursor that we related to, inevitably, when we sketched out the colloquium’s theme, and so the selection of proposals paid attention to researchers interested in how our contemporary media can be related to a wider history of visual practices which may not begin with Warburg, but certainly find an important moment in him. As for Farocki, he is also not named in our called, but is still referenced with his concept of “operational image,” a very important one in the discussions I mentioned earlier about the extra-aesthetic uses of media and film in particular. Operational images are basically images integrated into professional work processes – in factories, in security guard work, in the military sphere, in medicine – which fulfil precise functions within those contexts. And Farocki was the first to begin discussing these kinds of visual phenomena in a more theoretical way, trying to connect them to the forms and motifs of cinema. He noted, for instance, that certain types of labor associated with seeing have begun to disappear. In other words that a type of observational labor that people had to do in the field, in the factory, by the flows of molten ore, to see that everything was in order, has begun to be replaced with cameras which monitor this flow and which have begun to be augmented with all kinds of analytic instruments that can observe cracks and irregularities all on their own. Today, CCTV can not only monitor a space, but also analyze it, detecting suspicious figures, etc. Through this process, the visual labor of a security guard comes to be replaced by images and more complex forms of more sophisticated imagery: the human effort present in reading images has come to be replaced through new audiovisual forms, and this especially impacts the field of epistemology. This is why Farocki’s name was so prominent during the congress’s panels, but I would say there were also other relevant names. Eisenstein, for instance, was another important figure in our panels, with various proposals attempting to resituate his concept of montage into the new context of the medium of film and the field of its study, and the same process can be seen with many other classic concepts in film and media studies which have gained new connotations in the present. Thus, a researcher like Antonio Somaini, for instance, proposed using montage to discuss what happens in images created by neural networks – his concept of “neural montage” is one of the ideas that sprouted from the intersection of classic film studies and new media developments. Another name that was mentioned surprisingly frequently is Radu Jude, which is perhaps tied to a certain form of opportunism – participants will often send proposals involving the conference’s keynote speakers to make sure they hit the mark – but certainly it’s not just that; I think that his hybrid style of working with archives has something to say to us about how media have reframed our epistemic relation to history.

One highlight of the colloquium was the “argument” between Lev Manovich and Georges Didi-Huberman.

Yes, unfortunately conflicts always steal the show. I would say that the friction between them was somewhat inevitable: the two come from very different disciplinary backgrounds, and this incompatibility makes conversation more difficult, beyond just issues of form. Otherwise, of course, Manovich’s interventions were somewhat provocative, a sort of show-off attitude that makes things difficult for one’s interlocutors. But beyond such matters, the question Manovich asked Didi-Huberman is relevant. Didi-Huberman had spoken about the relation between atlas and archive and how when working with images, you can organize them in configurations that allow for a certain kind of reading (which is what he calls an atlas). And in this context it is legitimate to ask, as Manovich did, whether computers can’t also do something similar to what Warburg did, given all the programs using image databases for pattern reading and so on. In such a dispute there are no easy positions, you can’t say the two (i.e. Warburg and a computer) are completely different, it would be superficial. But it would also be superficial to say they’re the same thing. I think neither side’s position is easily defensible. Neither of the two participants had a predictable answer in such a discussion. Even Lev Manovich expressed some reserves regarding what you can do with the techniques of cultural analysis based on artificial intelligence. I think that if the question had been posed in a different way, Georges Didi-Huberman would have been able to enter into a conversation with him, would have had to actually think about it instead of dismissing the question. I think the question pertains to the major issue of what is happening to aesthetic categories in the age of artificial intelligence, and it’s a shame that the moment ended in an argument instead of offering a chance for dialogue.

Still, Manovich asked why Warburg is considered more important than Vertov given that the latter worked with more images…

I think some of the ways Manovich phrased his question were not the best. You can’t discuss Vertov quantitatively like that, that he had more images because you can count them frame by frame. It’s a ridiculous way of putting it. But the basic question he was driving at was in how far Warburg is still relevant when we have these contemporary techniques of pattern reading. And I think that the contrast between Warburg and a computer is more relevant than comparing Warburg to Vertov, which is pretty superficial.

A moment that was less discussed, but not overlooked, was Manovich’s intervention in the discussion with Sybille Krämer.

Sybille Krämer was talking about the reduction to the surface, to the 2D plane, as a cultural technique and a cornerstone of Western thought. Manovich’s question was whether the 3D modelling techniques and immersive technologies that are developing in the present might make this reduction to the two-dimensional obsolete. He was wondering whether we haven’t perhaps started working with images in a different paradigm than two-dimensional projection, given that immersive techniques are forms of virtual spatialization that no longer reduce space to two dimensions. Unfortunately, this discussion also reached an impasse and was not taken farther, but it started from how we are used to talking about the nuances of graphics, and writing more generally, the relations between writing and image as something happening in the two-dimensional projection, about how these things have been called into question by recent media developments. I’m sure these discussions will continue in the following years. In the end, the merit of these congresses is to broach certain topics rather than exhaust and shelve them.

Often when we talk about media we’re referring to productions of this and last century. But throughout the presentations there were also moments that drew attention to productions from farther back in time, such as physiognomic and anatomical drawings as precursors to the conversation around deep fakes.

Looking for precursors is, as I said, very relevant. Even if those drawings weren’t called media at the time of their making, nor did the term medium even exist, it is always fruitful to find parallels with earlier productions. This preoccupation can already be found in Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which is about how film developed as a response to certain pre-existing efforts, going back to what the Dadaists were doing. After film, we see new forms of reception, initially generated in completely different practices, in completely different areas of the art spectrum, which cinema then makes use of. It is sometimes fruitful to create this type of connection, to put things into perspective, within the study of film or contemporary media. In the end, I think that reflecting on media in the light of earlier forms of artistic production can be useful for both objects of study.

Deep fakes were in fact frequently mentioned throughout the presentations. As were Google Maps and memes.

The theme we proposed – Epistemic Media – was multilayered from the start. Moreover, congresses of such broad scope always try to offer as many potential avenues as possible to as many areas of a field as possible, including, for instance, things for classical film studies scholars, who can, for instance, reflect on the types of knowledge that come to be stored and disseminated through film. Thus, the congress’s general theme went from older forms to contemporary media applications and everyday platforms that organize forms of popular knowledge or that are used in cognitive or epistemic processes of various kinds. And, of course, the grand narrative that this whole story is part of is connected to the discussions in the last decades about the dangers of these technological transformations. People talked about digitalization and new synthetic images as the negation of the guarantee of truth that the classic, indexical, photographic image provided. People talked about how the internet’s proliferation and the dissemination of information had led to the disappearance of the authority attributed to the traditional press and the model of circulating and verifying information characterizing the print age. Phenomena like fake news and deep fakes are connected to these fears. Fake news as a way of obtaining knowledge about today’s world (which the news used to facilitate) which becomes increasingly unverifiable, as conspiracy theories that used to be marginal now become mainstream. And deep fakes as images that, because of how they are produced and circulated, become unverifiable in their fakeness. Basically, we are speaking here about a certain kind of image fake that points to a historical evolution: from the point where the photographic image was seen as a guarantee of truth in certain contexts, and as evidence in court, to the point where we can no longer tell whether it is true or false. The challenge that the conference call proposed was, in the context defined by these dangers, to see other opportunities this new media landscape might open. To see not just new dangers to knowledge practices but also new knowledge practices emerging which take into account these dangers and work with new procedures, new platforms, to generate knowledge that overcomes them. Forensic Architecture was quite present in the participants’ discussions and presentations – one of the keynote speakers, Stefanos Levidis is even a member of the collective, and their entire activity is somewhat symptomatic for these recent efforts to function in this transformed epistemic context that contemporary media create.

Similar connections can be made in the case of Google Maps or memes. Maps are, of course, also somewhat prefigured in the congress’s theme, and I think that Google Maps is indeed an interesting example of an operational media that has been constantly enriched these last few years, with topics like military security, and was touched on in the presentation by Forensic Architecture. The discussion was about the resolution that Google Maps, or any other open-access platform of this kind, is allowed to have, where military satellites strategically maintain superiority, beyond privacy concerns. Moreover, Google Maps is also relevant as an instrument we use every day. It is a kind of vernacular practice: we use maps in an augmented media format to find out what a street looks like before walking down it; we restructure our everyday experience in a way we did not before, not even 5-6 years ago. It is thus a palpable testament to the ways in which media interact with our everyday practices, beyond professional or research context, within the very fibers of our everyday experience.

As for memes, for a media historian, you can compare them to earlier forms of humorous images, caricatures, for example, with which they share some similarities. In contrast though, memes are caricatures that function based on seriality. They work, first and foremost, based on networked processes and how the image is replicated, giving the possibility of creating a new joke using the same visual template that has supported other jokes in the past. The success of the meme comes from the fact that it uses something extremely stereotyped in a new way, as a good meme is not one that uses an image never before circulated or completely new: it makes full use of the properties of an image that, in a traditional way of thinking, would be its drawbacks. Unlike a classical image, here the image needs to have been used: the more used, and the more novel the effect you can obtain with it through a joke, the more successful it is. The criteria for judging a meme stem from this network and serial logic which still connects to a certain history. Memes thus also contribute to this new epistemic climate of contemporary media.

On the colloquium’s last day, a series of science films produced by Alexandr Sahia Studios, curated by Ana Szel, were shown. What was their place in the context of the colloquium?

The screening was managed by Ana Szel and Gabriel Filippi, and it was, of course, an important moment, because it allowed us to sample a local tradition of epistemic film work, namely the tradition of science film. Of course, some of these films have an element of ridiculousness, but that is generally part of media studies’ interest in these materials, which history augments with properties they did not have initially. I am happy to see that more and more such materials are being rediscovered and screened in Bucharest.

What conclusions can one draw from the congress?

I already talked about what impact the congress had and where it fit into the field’s international context, but I think it is also important to talk about how it relates to what is going on in Romania. The colloquium was not just a thematic extension of the local discourse on film, as film analysis here is still largely confined to an authorial direction, focusing less on any other uses of film besides aesthetics or entertainment. As I was saying, these things have begun to change, and there are some very interesting projects in Bucharest. You can see different directions forming, such as what my friends at Image and Sound have been doing. So, this thematic extension is still important, but what I think is more important about this congress is that it has contributed to a more solid academic positioning of film and media studies, which are not yet visible in Romania as prime scientific fields – you can see this in the dearth of film and media studies programs at the moment. The NECS colloquium, besides everything else it has done, brought to the forefront the field of media and film studies in Bucharest and turned them into a magnet for interdisciplinary research in Romania, for just a few days. We had many participants coming from outside the field, philosophers, anthropologists, social studies scholars, who had their own conferences here. They have begun working, within their fields, with topics that have brought them into contact with media scholars, and I think this is a positive change for everybody.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Bogdan Balan

Bogdan Bălan is a cultural journalist, art critic and cultural worker. He has collaborated with Goethe-Institut, Savvy Contemporary, Scena9, among others....

Comments are closed here.