During his 4-year directorship at the Czech Centre, I spent many afternoons chatting to František Zachoval in his office overlooking Piața Universității. His curiosity about the local actors, their connections and respective positions was always a source of heated discussions. I returned to Bucharest almost at the same time as he took his position, and it can be said that our understanding of the scene grew simultaneously, and we meet in almost all of our analyses. It was therefore a great pleasure for me to record this brief conversation with one of the cultural actors who was most relevant for the Romanian arts scene in recent years.

What was your background before you came to Bucharest as the director of the Czech Centre?

I graduated as an artist from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, and then moved on to a more theoretical practice. I am one of the co-founders of Artycok TV. I was also head of the Digital Laboratory, an independent space at the Academy of Fine Arts, which provided practical courses for the students.While I was at the Academy I moved to Berlin, where I was a foreign correspondent for several cultural platforms such as Vernissage.tv and was thus able to understand the contemporary artworld. During that same period, between 2010-2014, I organized several projects with Romanian artists: I curated a show of the Bureau of Melodramatic Research in Školská 28 Gallery and I organized a very large conference on the theme of exile in which I invited Ștefan Tiron to take part. Then I applied to the open call for the director position at the Czech Centre in Bucharest and was selected. I started in March 2015, so almost 4 years ago.

What were the requirements in order to become director of the Czech Centre – in Bucharest and in general?

There are 3 steps in the application process. The first one addresses the applicant’s capacity to lead a cultural institution for a longer period, so it is important to have had this experience for at least 3 years. In the second phase, the applicant must propose a project and in my case I looked at how to connect the creative industries with sponsorship. The third step requires the applicant to confront their virtual project with the specific conditions of the country where the Centre is located.

Does the Czech Centre have an overall strategy for all of their branches? How much freedom does the director of a branch have to decide his or her own strategy?

The director has a free hand to create their own program – they can make a specific offer for the specific conditions in which they find themselves. On the other hand, the general aim of the Czech Centre is to raise awareness of our own culture, using the means each director finds most suitable. Some branches promote the Czech Republic through Vaclav Havel or Milan Kundera, but that was obviously not my interest. I was more attentive towards the local cultural scene and trends, rather than pointing out again and again simple facts about the Czech Republic.

Let’s start unpacking the 4 years you spent here. What is your perception of the visual arts scene: how is it connected to the other areas of culture? What do you think are its strengths and what are its weaknesses?

To me, the visual arts make for the most underestimated field in terms of public funding; institutions have no idea about the main challenge in this field, which is production coupled with presentation (display).

In Romania there are 2 separate scenes, one in Transylvania and one in Muntenia. From the beginning, I wanted to understand why the Cluj scene had so much visibility. To me, the painting production from this school takes no risks, it is very flat. One can find in other countries the same practice, the same approach – for me, it is really not stimulating. Some of the artists from this scene might be more interesting than others, but overall I could not support much work coming from there.

I should mention that the Czech Centre embraces proactive diplomacy, in the sense that not every event needs to be connected to Czech culture – on many occasions, we created and supported projects that Romanians required, thus filling gaps, rather that adding more unnecessary events on top of others.

You mentioned the Cluj and Bucharest scenes, do you think there are art scenes in other cities as well?

Except for Cluj, which is remarkable for the painting school and the market, none of the other cities really have something specific. In Iași there is the art school and there are a couple of theoreticians, so we could say that there is a small scene there. I don’t think there is a scene in Timișoara: there are no striking artistic personalities and their big event, Art Encounters, had a terrible first edition, something like a showroom for the best Romanian artists, I didn’t see any concept, strategy or some kind of ideological aim, the second I didn’t even visit.

What do you think is characteristic of the Bucharest scene?

UNArte is characteristic of the Bucharest scene. There are few commercial galleries, all quite small, then the semi-commercial ones like Anca Poterașu and Eastwards Prospectus puzzle me, as they have no clear statement or curatorial vision. So for me it’s really UNArte running the scene: many teachers are a part of UAP and the Union owns all major gallery spaces and artists studios in the city. In the 90s, the Czech UAP was completely dissolved, and we started from 0 and it was quite positive moment. Whereas the Romanian organization kept their properties and members 30 years after the political change. This moment I paradoxically appreciate because UAP became a social network for the oldest generation or a social meeting point for excluded artists. However, UAP has not upgraded in terms of content and is not attractive to artists from other fields or to young artists. UAP could, for example, offer their spaces, such as Simeza, Orizont, Centrul Artelor Vizuale or Atelier 35, to young curators who could turn these dead places into cultural hotspots.

On the other hand, places like Salonul de Proiecte, Tranzit, ODD and Macaz are still the minority. Perhaps Salonul has become more financially stable recently, but with most of these spaces it is impossible to have a coherent approach for a longer period. Many projects here host one another as spaces are constantly lost. These initiatives are of course more valuable than the projects proposed by UNArte and UAP, municipality’s agencies. The city has the potential to have more spaces with a comprehensive and stable program, but city agencies such as Arcub and Creart create public events without any kind of vision, sort of copy-paste of TV productions. This city is responsible for a long-term vision in respect to culture: what kind, for whom to produce it. But the leaders of Bucharest and of the state are using culture to their electoral means. Every project supported or produced by one of these agencies bears a huge logo of Primăria București, something which I find is not sufficiently debated in the public sphere.

In your program you always chose to support the independent scene, either organizations or individual artists and curators.

We decided to work with artists and organizations considered unprivileged from the state’s perspective. Their proposals are never understood by the state institutions which should support them. We also ceased our support for big events which have been running for many years and which now receive the support of the state or are commercially viable, such as TIFF; in their case, the visibility of the Czech Centre is very small and their budget is 100 times bigger than ours.

Yes, it is also a fact that these large festivals not only receive the direct support of the state and are commercially profitable, they also use this in order to apply for small funding schemes, such as AFCN or CNC, designed to support independent projects, something which I find indecent.

It is more than indecent, it’s greedy. They would apply for a 200 Euro film license to the Czech Centre when the overall cost of the festival was something like several hundred thousands Euros – ridiculous. So immediately upon my arrival in 2015 I decided we would focus on small initiatives. The new generation needs a huge support: the mid-career generation already knows how to work sustainably, but the young one needs motivation and encouragement that they will be able to achieve something significant with their work.

Your predecessors were also big supporters of independent initiatives.

Yes. One important example is the fact that the Czech Centre is the founder of the documentary film festival One World Romania in 2008. In the beginning the Czech Centre ran this on its own, later an association was created, which for the last 2 years has been completely self-sustainable. We started another project which we support in its beginning with the aim of it becoming independent, Cinemascop Eforie.

What was not present in the program of my predecessors is this proactive diplomacy, in my case manifested as the creation of the Future Museum, a space dedicated to Romanian artists.

Tell me about the Future Museum.

Several things are important in its regard. First thing is production. In Bucharest there is only one medium-sized gallery, Salonul de Proiecte, which affords production costs and offers a generous space to artists. We wanted to offer local artists these 2 elements, production budget and a space. This is something that big institutions – galleries or museums – should be doing, but they are not.

The second thing is that our space here in the Embassy is very decorative, so it is a huge task for the artists to work with it. Hence, we showed sculpture, installation and videos, never painting, as we weren’t even allowed to hang things on the walls.

The third thing is that we focus on solo shows, either the artist’s first public presentation, a semi-retrospective or the display of works made by important Romanian artists who either had left the country or had not shown locally for many years.

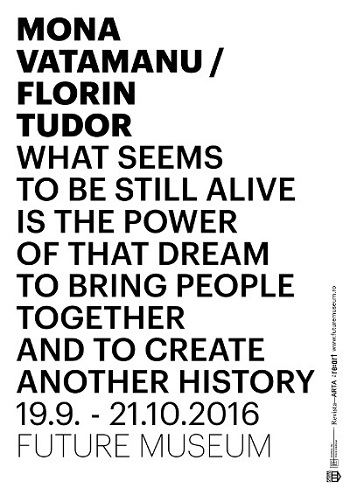

Finally, we invested in mobility: we showed work from Tatiana Fiodorova from Chișinău, Vilmos Koter who is from Miercurea Ciuc, Anca Raluca from Arad. After that we showed work from émigré artists such as Ovidiu Anton, Anetta Mona Chișa and Andrei Ujică. We also exhibited a new piece by Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, who had returned after many years of living abroad and who, despite being two of the most important living artists in my opinion, hadn’t showed in Romania for 8 or 9 years.

I remember we were having many conversations at the time when you were setting up the project and I was telling you how much I appreciated the work, which it would have been the job of institutions such as the MNAC to do. It’s fascinating that someone running a foreign cultural institute is doing the job of our institutions. Moreover, the choices you were making showed a real attention to the needs of the scene: helping young artists, people who hadn’t shown for many years in Romania, people who were important yet they were not visible. It really shows a good level of research – perhaps you can discuss how you made this research, what tools you used, how you went about understanding the local scene.

It’s very simple. If you come here and want to work, you must find the niche, the field that is not covered. The structure of the Czech Centre is that each member of the team covers one field and I was responsible for the visual arts. Before creating the structure of the Future Museum, I attended all the openings in Bucharest and traveled as much as possible around the country to attend events that I found interesting. I met people who had been active in the scene for several years and knew what the local issues were – people like you, Raluca Voinea, Ștefan Tiron, Alexandru Polgar, Alexandra Croitoru, Matei Bejenaru and many others. One might say I met the right people!

Many of the projects you showed at the Future Museum were quite political, they took stands on various matters.

As far as I can see, artists here tend to react to everyday issues. If you are living in a country where many things are not correct such as transparency, lack of responsibility, clientelism, nepotism, basic human rights, etc. then you automatically develop a specific practice. And visual art is one of the few mediums where self-censorship is not so present…

What about these projects you initiated that are very specific researches on Romanian issues – I am referring to the two projects on public space.

Jakub Charousek, my colleague from the Embassy, and myself, together with a variable team of collaborators, are running the platform Protect Public Space. We monitor, photograph and research not only monuments, but also the space between private properties – the actual public space, decorated with mosaics, welcome signs, art works and details on buildings of very high aesthetic quality – as it was built between the 1950s and the 1980s.

The official political discourse in Romania is anti-communist. It is a manner of not dealing with and not understanding recent history. It is a way of denying a period in its totality.

Therefore it also denies the entire artistic production of the period, including public constructions. This legacy must be researched and published, first of all to raise awareness about it. Recently, I was spending my weekends at Predeal and I discovered the unbelievable train station there, one of the most incredible in Europe, even in the world! However, it is not being taken care of, no money is being invested in its preservation or reconstruction. Romania is full of these fantastic buildings and arworks, particularly in the coastal area, as one can discover in the book published by Alina Șerban, Enchanting Views.

So far we have put together an Instagram account to showcase images of these spaces. We also have an offline project stemming from our research, Cinemascop Eforie. Last summer, with the help of the local authorities in Eforie Sud, we cleaned the outdoor cinema, then organized a 5-day film festival in it. It was an incredible success and we became convinced of the importance of leaving our Bucharest comfort zone.

Right now we are preparing a printed map, which will cover every corner of Romania and show the location of these jewels. So far we have gathered a huge archive of documentation, which will become publicly available in time.

What is your take on the art market in Romania?

It is very conservative. Look at the collection at MARe! It is just an investment. It’s funny that these collectors are trying to be smart and they hide behind a “respectable” art institution. To me, it completely lacks credibility: they are only interested in money. All over Central Europe and the Balkans, local biennials hide the financial interests of a collectors. What is more, these biennials are usually one- or two-man shows – think of Bucharest Biennial, even Art Encounters. They do not involve discourses from more institutions or personalities, something that would balance personal taste and widen the problematics.

This might be a typical impasse in Romania, where people tend to become the institution because of the lack of actual institutions.

It’s a question of precarity, but also a legal question: I was amazed that in order to found an NGO, I had to ask the permission of my neighbors! Nothing of the sort is required in the Czech Republic. It is very difficult to run something in this crazy bureaucracy.

So, what have you learned from your stay in Romania?

This was my second long stay abroad after Berlin. I spent more time learning cultural codes. Stereotypes are able to destroy individuals and I learned that we cannot simply judge people according to their cultural background. However, understanding between people also passes through the decoding of our cultural patterns.

Where to now?

One of the reasons I am leaving my position a bit earlier is that I won the competition for the position as director of the Gallery of Modern Art of Hradec Králové. The collection features more than 6,000 pieces from modern, avant-garde and 19th C artists. I will focus on visual arts, so back to my initial training! But the experience at the Czech Centre, where I was multitasking daily and dealing with all the cultural fields, will be very useful in dealing again with the visual arts.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.