We are at a critical point in the history of Roma movements in Europe. Day after day, we receive news of pogroms, killings, shootings, beatings, family separations, school segregations, rapes, and homophobic violence against our people all across the continent. The response from some Roma artists and writers is anger.

Anger is and has been a creative force that has produced counter-narratives of a world that is changing. As long as there is this anger, it is clear Roma have not been sedated into accepting the injustices and imposed divisions. Anger is a driving force that names the oppressor and clearly states: It shall not pass. It brings Roma people together, encouraging them to develop artistic expressions and aesthetics, which is helping shape a resistance. While there is anger, there is the possibility for a different future, a queer and feminist one.

Recently, I have been critically reflecting on centuries of knowledge production and representation of Roma by gadje (non-Roma) cultural workers, scientists, and scholars. As a PhD student studying culture, with specific interest in gender and cultural productions, I am working on decolonizing the minds of white Eurocentric art scholars and the general public in relation to the European Roma.

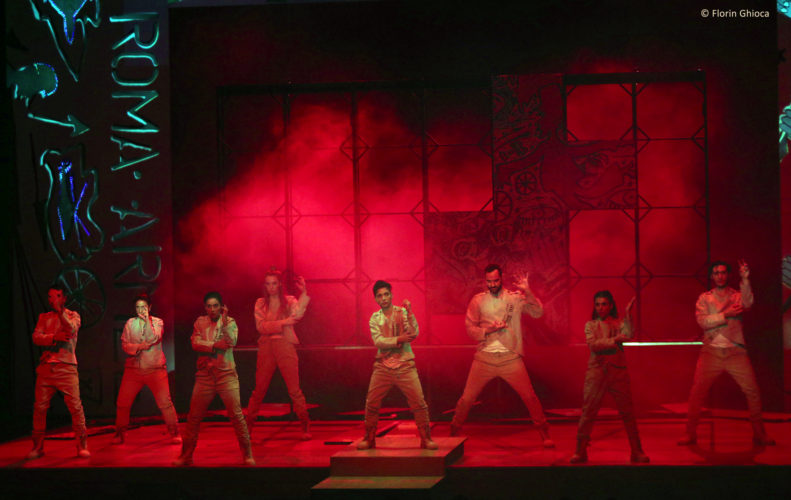

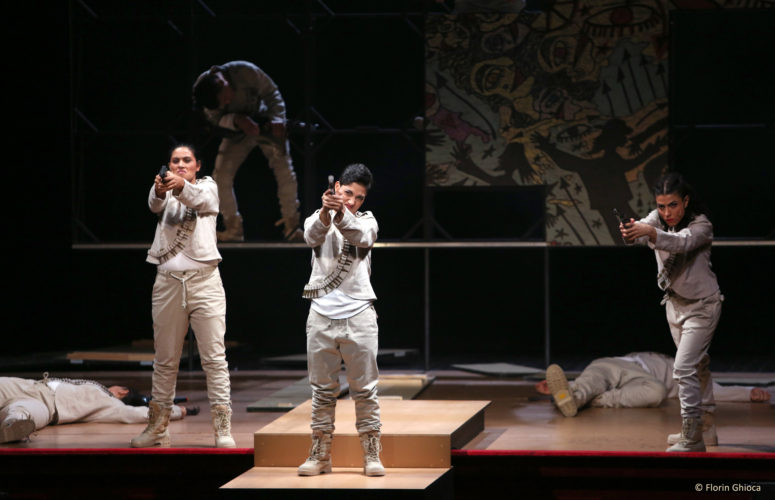

One play that has helped pave the way for a different future for European Roma is Roma Armee, directed by Yael Ronen and based on an idea by Simonida and Sandra Selimovic. The play, which premiered in 2017 in Berlin, tells real-life stories of Roma and their gadje comrades, rejecting the colonial legacy and shifting towards a self-defined and negotiated representation. This counter-narrative lives on the boundaries of documentary theatre and theatre of revolution.

The radical potential of this play lies in the necessity of actresses and actors to self-reflect on practices that have shaped the Roma conditions, which creates a sense of unity and belonging from within. As Romani queer feminist Mihaela Drăgan states in her call for a Roma feminist and queer revolution: “We cannot think of uniting with others until after we have first united among ourselves.”

Mihaela’s timely call asks us to reflect upon self-internalized mechanisms that have created divisions and to embrace the voices of those who might be the loudest but who are perceived and constructed as the most vulnerable and ostracized in the Roma community. Roma Armee effectively offers a queer and feminist strategy to transform our present and create a different future in unity.

It is clear that at the heart of this revolution is Roma-ness and queerness. Yet, simultaneously, as Katarzyna Pabijanek importantly observes in her review, Roma Armee critically reflects on the violence of heteronormative patriarchy and names the theatre as an institution that was and still is historically complicit to creating misrepresentations and perpetuating stereotypes of Roma in a painfully familiar way. Pabijanek’s contribution to decolonization of the theatre is unquestionable, however, together with the tendency of gadje reviewers who focus their writings either on the queerness or solely on the director, we lose what the Selimovic sisters and the Roma and non-Roma acting crew were so importantly communicating: a queer, feminist Roma narrative of resistance.

As a queer person of Romani heritage, my aim in talking about Roma Armee is to shed light on the importance of narratives that counter the colonial representations of Roma and queer Roma, I use the collective we as an act of resistance without the intention to hegemonize a cohesive narrative; the reality is that Roma experiences are diverse, context dependent, and fluid over time.

Roma Armee’s story is layered intersectionally, touching on race, sexuality, and class. Each act is topical and each scene adds to the audience’s understanding of the multiple forms of oppression Roma have endured. Being part of a Roma queer revolution means being a soldier who takes multiple fronts simultaneously. For example, it is never only about being a woman, it is about being a woman, a lesbian, and a Roma, as well as having been exposed to the trauma of poverty, segregation, and discrimination at school, being called the dirt of the earth, and being devalued by both heterosexual and queer whites and, often times, by members of our own community.

As the play’s co-creator Sandra says in scene five, reading a letter she wrote about her life:

“I am a lesbian. I know some of you don’t understand why I have to mention it on stage, why it should come as a topic in a show that is supposed to deal with Roma issues. But this is a show about us and I bring my entire identity into the show. I’m Roma and I’m queer, and I do not apologize for either.”

This statement asks for the recognition of interlocking identities. For some Roma, Sandra’s identity might not be “true to their ways”; for some gadje, Sandra might be seen as either a helpless victim needing to be saved or an exotic brown lesbian essentialized for her appearance and her exotic otherness. Yet by uttering her pride on stage, Sandra reveals herself as a heroine of a new wave, a new revolution. This revolution is one that encompasses all identities rather than excludes them.

The interconnections between race, sexuality, and class in Roma Armee are strongly expressed in scene four, which is called “Shame and Poverty.” In this scene, all of the actors speak of the names that were used to shame them for being brown or white. Mihaela has been called Negressa, Simonida “nigger-lips,” and Hamze “Ham se mahl ne Mark?” (Do you have a euro?), referring to the stereotype of a beggar, which is strongly associated with Roma in Europe. Sandra explains that nobody wanted to touch her at school because she was so dark. “They thought the color rubs off,” she says.

Riah, a white-passing Romani, says she is often miscategorized as gadje. This informs us about another misconception that has been historically reproduced, that Roma all look the same. In fact, Roma communities are diverse, and individuals vary in darkness and lightness of skin color. It is not unfamiliar that Roma parents are accused of stealing a child if it is blond and blue eyed, even though these children are their own.

This name-calling that gadje kids use on their Roma schoolmates shows us how white supremacy is a lesson taught to Roma children at a very early age. In those moments, Roma children construct a self-image of unworthy, dirty, unacceptable, despised, and ugly human beings.

The mutual constructedness of gender, race, and class becomes clear in the same scene when Simonida talks about period shame: “I made my own pads out of toilet paper. One day it fell down from my panties in the middle of sports class. I was so embarrassed.” Not having access to sanitation pads or tampons was not because her culture does not understand what tampons are, but because her parents were pushed to the margins of the society, denied access to employment, and making a bare living. Simonida had to work part-time to contribute to the home. All of this influenced the way she experienced her first period.

This traumatic experience has immense power in Roma Armee. The shame and fear Simonida felt is transformed into a powerful way of talking about stereotypical depictions of Roma as inherently dirty, culturally poor, and lacking basic social skills and knowledge of personal health and hygiene. It is an example of a counter-narrative that exposes colonial practices, and in this way menstruation as a topic becomes the driving force of the revolution.

Another way the play informs audiences how gender, sexuality, and class are articulated and negotiated by Roma is in the scene “Gay&Roma&Vegetarian,” which focuses on Lindy, a Swedish traveler who identifies as a gay vegetarian artist, actor, and Roma. Lindy takes a lot of pride in coming out as gay, yet he feels discomfort doing it: “I’m proud to be gay, but it’s complicated. To be gay is filled with a lot of self-hatred. I’m openly gay but not always…”

This decision—to choose when to be “out”—makes Lindy feel as if he is betraying the gay community. “I’m not openly gay because I am afraid to be rejected. I want to be loved and accepted, I want to belong. And sometimes I am not openly gay because I am afraid of my own security.”

Fear of rejection and abandonment, which are connected to his sexual identity, are fears many of us Roma gays live with. “It would be easier to be a straight man,” Lindy adds. “I have no problem being gay on stage, but I feel happy—gay—when people think I’m a straight man and when gay people say I’m straight acting, but that feeling is something I am really ashamed of.”

Lindy exposes a common misconception about queer Roma. The Roma gay man often occupies two positionalities in the white gay male’s imagination. The first is as a victim of persecution, in which the persecutor is part of the Roma culture, where it is “natural” to reject the queer. This misconception is often reproduced in academic texts and popular culture, such as the movie Brothers of the Night, where Roma men who are either gay, bisexual, or have sex with men live under the veil of secrecy and have multiple lives. This representation coincides with the stereotype of Roma as untrustworthy and liars, which is then reproduced in majoritarian queer communities.

The second common depiction is the oversexualized Roma macho, who is always straight-passing and uses his masculinity as a toy to fulfill the white gay man’s desire for a hypersexual masculine object of consumption. His only use is production of pleasure—serving the purpose of an object, a consumable good, rather than as a subject who constructs his own identity or subjectivity.

Lindy is aware of all of these markers and knows his place, as a Roma gay man, in the hierarchy of power. He takes pleasure as well as pain in both disidentifiying with straightness and passing as straight, even when performing a straight-passing gender identity is a conscious choice that might save his life. Lindy also conveys how to heal the traumatic injuries brought upon him as a young person growing up. It is through an unlearning of images and representations that have defined the ways our bodies move in space, the ways in which we assume a right to exist the way we are, and how to redefine our bodies and claim spaces for the sake of our own pleasure.

A Roma Revolution

Roma Armee is a revolutionary generational shift because it goes against everything that our parents taught us to do or be. Amiri Baraka, a writer from the United States, delivered a speech in 1965, later published in Liberator as “The Revolutionary Theatre,” addressing the importance of anger as a decolonizing strategy in theatre. Baraka defines the revolutionary theatre as one that must expose; it must attack and accuse everything that can be attacked and accused. Revolutionary theatre is shaped by the world that surrounds it and it shapes the world around it. It shows the victims that they were victims and guides them to a place of strength, even through violence, killing, anger, screaming, crying, or murdering—whatever is necessary to move someone to understand the world as it is. Roma Armee does all this.

In scene nine in the play, Sandra refers to Malcolm X in a call for a Roma revolution. She meditates upon the centuries of peacefulness that have characterized the Roma communities, even in times of adverse violence. Yet Sandra questions nonviolent resistance as a strategy and manifests a different type of revolution:

“The Roma revolution is the struggle of the nonwhites of this earth against their white oppressors… Revolutions are never peaceful, never loving, never nonviolent. Nor are they ever compromising. Revolutions are destructive and bloody. Revolutionaries don’t compromise with the enemy; they don’t even negotiate. Revolutions drown all opposition; the Roma revolution will burn everything that gets in its path. Europe is the last stronghold of white supremacy. The Roma revolution, which is international in nature, will be sweeping down upon Europe like a raging forest fire.”

This symbolic call for violence is an intervention. It comes from the need to protect Roma and communicate that Roma are not here to compromise but to de-mask the white aggressor in an act of bringing about historic justice. This affective intervention on the stage, in Roma Armee, serves the deconstruction of centuries of oppression, exclusion, violence, slavery, forced sterilization, and homo-lesbo-bi-transphobia under the heteronormative patriarchal system that we live in.

This piece originally appeared on HowlRound.com on 12 March 2019.

Roma Armee is at TNB on 26 June 2019.

POSTED BY

Arman Heljic

Arman has obtained a degree in English Language and Literature at the University of Tuzla and an M.A. degree in Critical Gender Studies at the Central European University. He has been an activist in y...

Comments are closed here.