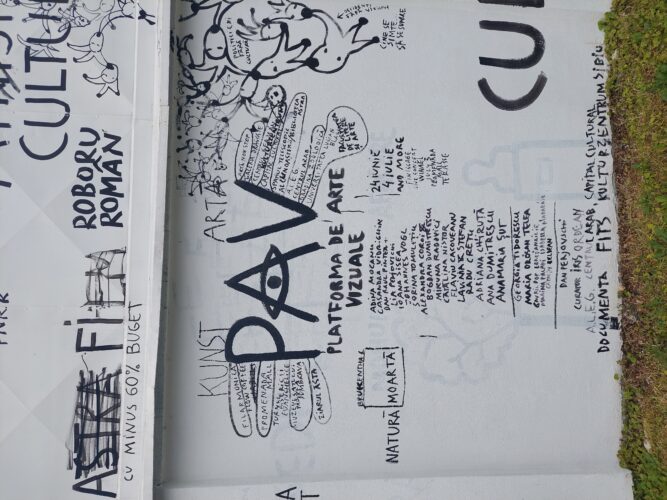

The first edition of the Visual Arts Platform took place in Sibiu from June 24 to July 3, 2022, at the initiative of Dan Perjovschi and curated by Iris Ordean, with the support of FITS, documenta15 and the German Cultural Centre in Sibiu. The event brought together Romanian artists from Sibiu, but also from other cities, even from Berlin. For the very first edition, the Platform was fruitful and ambitious: the public could get accustomed to art or discuss art twenty-three times, through lectures or installations in different places, from the Zoo to the mall.

As I arrived in Sibiu, I received, amongst other things, the VAP program in the form of a map. And this is because the dimensions explored by the artists and organizers were very diverse, and the curious art seeker had to go through various places in the heart of Sibiu. All said and seen. For a clearer picture of the events and their stakes, I’ll start with an outline of the discussion with Iris Ordean. Then, we’ll go through the proposed VAP route as we covered it.

Why VAP and alongside whom?

VAP started as an initiative to bring together multiple artists: it started with locals, then artists from other parts of the country and abroad got invited as well. More specifically, artists from Berlin were invited through the German Cultural Centre. Sibiu became a meeting place for artists to meet other artists and the public. Amongst the guiding ideas of the VAP were decentralization and community. Moreover, the organizers accompanied the artists in choosing of spaces and the management of relations with the public, a dynamic entity made up of very different segments. Starting from some already existing local nuclei, they have created the opportunity to meet guests from elsewhere and will expand collaborations in future editions.

Like any beginning, VAP is also an experiment designed to test two possibilities: recreating a well-organized artistic community by bringing together local artists and establishing a dialogue with the public that allows artists and organizers to get to better know the many, very distinct people to whom they are or might be addressing in the future. In fact, a concept around which documenta15, the ongoing project in Kassel, is centered is lumbung, borrowed from Indonesian culture. The term is used to define a type of barn where rice is stored and made available to the whole community. By extension, lumbung is used to define the sharing of resources and knowledge towards which the artistic community envisioned by the VAP aims.

The VAP map guides us

The route started with Dan Perjovschi’s Wall because it’s relevant to the VAP: it’s experimental, and playful, and it pops up where you least expect it if you didn’t already know about it. It presents event-images[1], that is, not representation-images that point to something outside themselves, but images that become events, whose meaning lies not only in their content but above all in the effect they trigger. While in terms of content, the Wall is critical and questions society and the way things work, the event dimension is related to the medium through which it is delivered, i.e. an open space, central to the geography of the city, but also ordinary due to its position behind a bus stop, in the core of everyday life. In the case of the Wall and all the works in the VAP, the event happens in the form of the encounter with viewers.

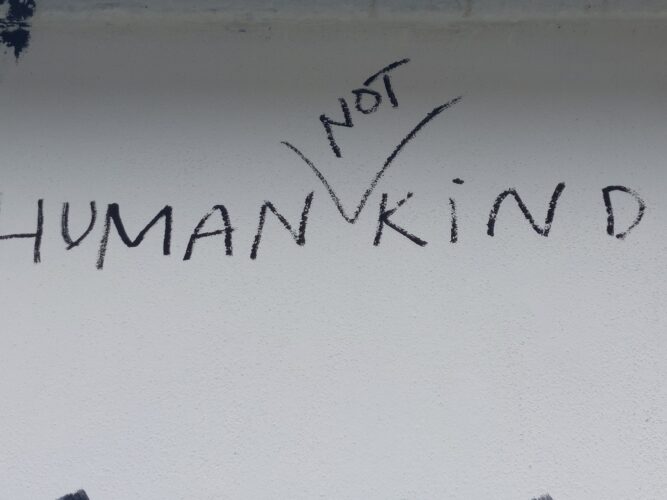

You wait for the bus in the center, near the Radu Stanca theatre. Behind the stop runs Dan Perjovschi’s Horizontal Newspaper, an ever-changing chronicle of the big and small things in the world. The newspaper is constantly changing not only because the things it talks about are changing, but also because the artist’s ways of expression are always new, and the emotions he seeks are nuanced, since he digs to the core. Dan Perjovschi’s technique resembles the OULIPO literary movement in France, which set out, among other things, to experiment with the literature subjected to various constraints. Perhaps the best-known text of this kind is Georges Perec’s novel La Disparition. But what was the constraint? To write a novel without the vowel e, the most commonly used vowel in French. In Dan Perjovschi’s case, the constraint is also a formal one, and the result is the meanings of words and images merged into formally minimal and semantically maximal constructions that come off as forced. He resembles drawing through poetry, as Hrabanus Maurus did in De laudibus sanctae crucis or, more than a thousand years later, Apollinaire. He forces the language and brings out the new, drawing on such prosodic and poetic elements as alliteration, chiasmus, and rhyme. All this can be found on the Wall. Beyond it, the viewer is free to do as they please: to move on, because they finds art that is not in the the museum uninteresting and doesn’t consider it art, they can try their own hand at writing, or they can stop and look. When they stops, and if they do, they tends to sit and take in everything.

Another stop on the map is the mall. If you look around as you wait at the bus stop, you might notice something on the wall behind you; it’s more complicated if you are at the mall. On the ground floor, next to the cinema, Ana Dumitrescu[2]‘s documentary entitled Trio was screened and portraits of the VAP participants, also by Ana Dumitrescu, were displayed in film poster format. Small figures in huge frames, in the even bigger frame of a mall cinema that swallows up images and risks overshadowing them with bigger, more visible ones. Exhibiting at the mall means taking the risk of getting lost in the garish, sensory-stirring landscape. But it also means seeking out an audience accustomed to other kinds of aesthetics and offering them new things, if they have eyes to see and want to understand. ALEG Sibiu’s installation, for example, didn’t find a very convincing formula and melted into the surrounding garish flow. Instead, Johannes Vogl’s huge shoe wheel, Walze, lured visitors, and, despite the prohibition on the shy and rather invisible sign at the entrance, they were all tempted to reach in, feel the shoes caught in the wheel and pull them out. It fitted into the flow without getting lost in it, as passers-by also stopped in their tracks for minutes. Somewhat harder to find, the installation by Ioana Sisea, From Here to Here. It will melt in four thousand seven hundred and eighty washes, proposed an autobiographical fragment printed on huge pieces of soap. If the text might go unnoticed and remain hermetic, as the viewer had no access to the personal references of the printed fragments, the material, the raw soap, might make one reflect. Also, in the space dedicated to exchanging and rapid consumption in the mall, it contrasted with the environment because it proposed precisely the play between durable and consumable.

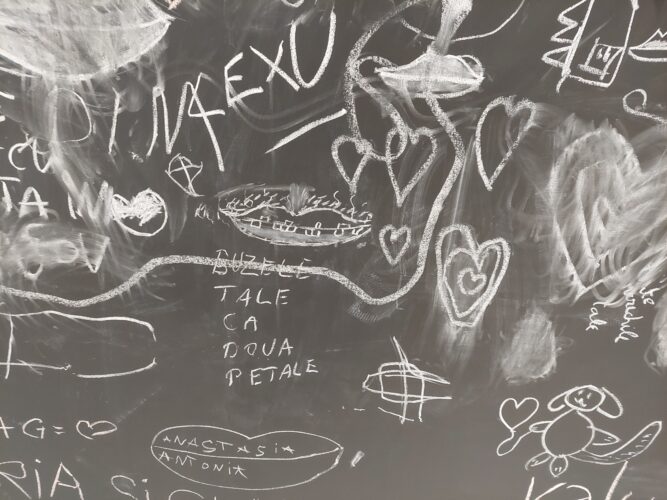

On the top floor, Anamaria Șut installed another kind of interactive wall, Les lèvres rouges, as a continuation of a personal design project: brooches in the shape of red lips, powerful symbols that are prominent in fashion mythology. As part of the VAP, the public was invited to participate in a collage of red lips and short texts. The exercise generated many interactions: some participants joined in while others hijacked it with classic phone numbers and newer Instagram IDs. The guard also joined in the exercise: he was the appointed censor, he erased the insulting inscriptions, and also did exegetical work. And so we witnessed the next scene: after a few moments of agonizing hesitation, he wiped off the lgbtq inscription with a sponge, after having wiped off a racist inscription moments before. In the end, the wall became an ever-changing palimpsest, bearing vestiges of a very diverse audience, often asked to decode a new message, to which he often reacted spontaneously, and therefore more authentically than an informed Art-educated audience would have done.

The installations in the mall played, perhaps, the best card of surprise, giving rise to a type of aesthetic experience that Hans Robert Jauss talked about in his Apology of Aesthetic Experience[3] that arouses a spontaneous reaction and that precedes the reflective stage, and then comes to renew the viewer’s perception. The choice of unusual spaces for this first edition of VAP seeks not only the spectator who is familiar with art, as mentioned above, but also the spectator who has gone out to buy something, have a drink, or see a film. However, a viewer usually uses his free time and therefore is already more willing to be drawn to something unusual than he would have been in his busy, working time.

From the center, we went to the outskirts of Sibiu, to the Astra Museum and the Zoo. In these two unconventional spaces, we also saw Casandra Vidrighin’s installation Wild Instinct (at the Zoo) and Adina Mocanu’s Breathing Eyes (at the Astra Museum). Both exploited the chosen spaces: in Wild Instinct, the movement in enclosed spaces – the three girls in the video are in some sort of cave, with uncertain viewers sitting somewhere at the end of the tunnel – while in Breathing Eyes the human tendency to make inhabited or familiar spaces out of anthropomorphic ones, having a head, eyes and a body. Adina Mocanu’s installation, though hard to find around the museum, played wonderfully with space and imagination, literally illustrating windows that have eyes and evoking, perhaps only for some, the already famous eyes of Sibiu. Perhaps it would have been better observed at night, but even so, the installation has managed, with simple means, to recover an entire mythology of the living house and to animate an abandoned house, to take it, through installation, out of the museum circuit and to bring it back to life for a while. It would be a great thing if such installations would continue to rise throughout museums in a more accessible way.

Back in Sibiu, already in the space of the cultural circuit. The ASTRA Library brought back to the public’s eyes the Telescopic Space of Knowledge, designed and installed by Lia Perjovschi. It is an approach in which the idea of archive and encyclopedia meet and propose paths of knowledge that each reader-visitor is free to recompose, starting from various types of objects that have become objects of knowledge: from magazines to umbrellas, the objects are placed in constellations into which one can delve. The term telescopic, in the title of the installation, best captures the suggested experience: one can come, look around at a sea of objects and approach, sit, then delve into one of the paths. The idea of an archive is also explored in two other installations: the archive of the Simultan[4] Association presented on a monitor in the hall of the Faculty of Letters, and Sorina Tomulețiu’s Basarabia at the German Cultural Centre. Although positioned in a central space, the first installation still proved difficult to find because of the orientation of the monitor. The place of the installation – when the screen was working – became welcoming and bright once discovered, but after the problem of space came the problem of time; it was not clear how long it would take, the cutouts were hard to read and the selections of each of the students involved were unclear. The archives presented would have been much better showcased if the viewer had been a little more informed. The same uncertainty hovered over the video installation[5] at the Basarabia exhibition, as it could have started and ended at any time, without the viewer knowing how long it would take. In the exhibition, the artist revisited her family history through the eyes of her Bessarabian grandmother, against the background of the wider history of Bessarabian refugees in Romania. The fragments of conversations exhibited and transcribed were amongst the most powerful parts of the exhibition, as they gave a direct, raw account of the refugees’ situation:

S: “What do you mean it was raining with rocks?”

N: “They were throwing rocks at us on the train.”

S: “Who?”

N: “They were asking why we were leaving. The Russians, the Jews…”

S: “Well, the Russians… the Russians…”

N: “All those who were present.”

S: “The Russians told you to leave. Why would they throw rocks at you?”

N: “Because we did leave.”[6]

Quite close to the German Cultural Centre, at the Philharmonic, lurked a kinetic sculpture by Ștefan Radu Crețu, placed near the old fortifications. With slow movements, it filled the space and stopped passers-by. Like any kinetic sculpture[7] from Galatea onwards, the orange-red hybrid also grabs you with the strangeness of the animated object. But it does so without being predictable. Like the rest of the artist’s work I discovered on this occasion, the metal bird shows a cultivated preoccupation with the geometric cutout of shapes drawn from nature and playfully rearranged into a bestiary of their own. Although bestiaries, hybrids, and automatics are very old figures and themes in European art, the bird in front of the Philharmonic looked very vivid.

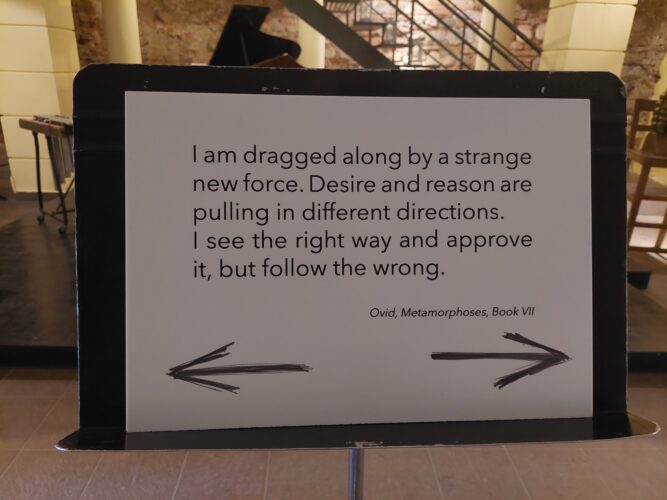

In the innards of the Philharmonic, there was another game with the living and the animal, in the Cellar. Alexandra Coroi and Bogdan Dumitrescu proposed the installation Imagined Bodies, an encounter with Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Petruț the Tiger, much more ferocious if you see him at the Zoo instead of on the screen. The multi-channel video installation sat nicely in the two tunnels beneath the Philharmonic, where the silence and darkness enhanced the background sound. The sounds were full and enveloping like shells, and the narrative felt much more real in the dark. It’s easier to imagine things in the dark, and so it was with this installation. The narrative, a kind of sensory prose, propelled you through many ways of being corporeal through the vocabulary used, charged with sensory force. The use of the second person and direct speech sped up the immersion in metamorphoses, peppered with references to other metamorphoses:

“They isolated you in the bathroom of a greek hero, I can’t recall which one. You stay there and regard all the corners from up and down. A blatta orientalis ascends straightly, then stops in the middle where the wall is shriveled and a piece of dry chalk falls. You close your eyes and hope that when you open them, you won’t see this anymore, you wish that it would disappear in the coarse and hot and nice sand. You trace your fingers through your hair, following the contour of your forehead…[…]”

The main subtext of the installation, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, serves as a source of interrogation of corporeality. In the medieval period, Ovid was not only perceived as a poet but also as a philosopher of nature, mainly due to the beginning of the Metamorphoses, where he talks about the world’s making and natural order. Likewise, here he is recovered as a pretext for exploring corporeality in movement, in the transition from one form of life to another. The way in which the relationship between man and animal is played out is reminiscent of the theories of French anthropologist Philippe Descola. While he rejects the classical nature-culture paradigm, he proposes four distinct forms, four ontologies[8] built on the axis of the relationship between interiority and corporeality through which different types of societies understand the man and the natural world. In the two video installations, bodies are imprinted with two types of movement: a mechanical movement with gestures taken from yoga, and a transformative movement as the body always seems to morph into another body. In the video installation using footage from the Zoo, human movement appears in the background and the Siberian tiger appears in the forefront, beyond the bars. It’s an apparition when you see it live. You stop to measure the powerful, living machine, with the petty, unutterable satisfaction of knowing you are safe, beyond the cage. The video installation plays with the nuances of the encounter: the massive animal and the fragile human body, the unnatural movement of the caged animal, and the hypocrisy of enjoying the spectacle without really being in danger, but feeling a shiver of fear watching it in the flesh, red in tooth and claw.

En fin

With stops, turns, and searches, the route proposed by the VAP in this first edition was more complex than we captured it here, where we only included the points we got to. I think the merits of VAP far outweighed the shortcomings, and the exploration of new spaces, together with the openness to a new audience, less used to contemporary art or not used to it at all, showed, on the part of the organizers and artists, the assumption of vulnerability and taught them to place themselves in an unpredictable scenario. The social experiment, present in most of the proposed installations, linked the works in a cohesive sequence of dialogue and updated an important dimension of the artistic act: communication. A commonplace with regard to contemporary art is elitism or hermeticism. However, the experiment proposed by VAP came to suggest opening up the artistic community to new spaces and getting art closer to more people.

[1] Thomas Golsenne, « L’image contre l’œuvre d’art, tout contre », L’Atelier du Centre de recherches historiques, 06 | 2010. http://journals.openedition.org/acrh/2059.

[2] The movie Trio, a documentary by Ana Dumitrescu, produced by Jonathan Boissay, featuring Gheorghe Costache, Sorina Costache and The Violin, 1h22min, 2021.

[3] In Hans Robert Jauss, Pour une esthétique de la réception, trad. Claude Maillard, Gallimard, Paris, 2001, pp. 135-171.

[4] The Simultan Association, Simultan Media Archive. Curator Maria Orosan Telea, West University of Timișoara. Students: Gavril Pop, Loredana Ilie, Marina Paladi, Isabella Madarász, Cătălin Beldean.

[5] Fulgerații din România, documentary by Mina Minchevici and Angela Zaporojan between 2010-2011.

[6] 4th part, Aruncau cu pietre în noi / “They were throwing rocks at us.”

[7] Titled Everything hybrid.

[8] Philippe Descola, “Cognition, Perception and Worlding”, Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, Vol. 35, No. 3-4, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1179/030801810X12772143410287

POSTED BY

Alexandra Ilina

Alexandra Ilina is lecturer at the French Department of the Faculty of Foreign Languages and Literature (Bucharest University), focusing on medieval literature, iconography derived from literature and...

Comments are closed here.