Yevgeniy Fiks (b. 1972, Moscow) is a multidisciplinary artist based in New York. He was raised in Moscow, where he started his artistic education, as a social realist painter and continued his studies in the US. Soon after the end of communist regimes he migrated to the US, becoming part of more diasporas: queer, Russian and Jewish. Yevgeniy Fiks is concerned about history, often forgotten stories, developing a research based practice oriented to a complex exploration of his identity influenced by the tensed cold war mythology. Fiks had articulated his artistic language connected to the diaspora studies field. Among other subjects one of his research and reflection interests is the Jewish diaspora, or, more specifically, in his terms: the Yiddish diaspora. In his artistic manifesto, Yiddish Contemporary Art, Yevgeniy Fiks imagines a visionary diaspora, creative, political and not only highly diverse, but intersectional. His process is one of queering Jewish translational culture, visualizing a future connected to both tradition and imagining a secular progressive culture.

How is the East you are thoroughly describing in your art seen in the West? How do you place yourself inside this binary?

I’m an immigrant artist first and foremost. And I think this identity is the underpinning for every art project that I’ve made and almost all of my art works were made in New York after I settled there in the mid 1990s. I came to NY at the age of twenty-two, fully formed by then as a person and artists in Moscow, a city I left only a handful of times in my twenty-two years. I had never been abroad outside of the Soviet Union until I left for good for the US in 1994. But I guess, this physical immobility during Communism was experienced by so many people in countries of the Eastern bloc, especially those who came from the middle or working class, not from the cultural political communist or state elites. Twenty-five years later, I still see a very strong attachments to Eastern Europe, to Moscow in particular and many projects that I’ve done are about unresolved issues between the West and East, in particular the US and the former Soviet Union. About finding the East within the West, about strange interdependencies and overlapping, such as for example, the history of American Communist Movement or the shared homophobia in the McCarthy-era America and Stalin’s Soviet Union.

My vision of the East is definitely extremely limited to my Moscow experiences and I have yet to engage seriously with the histories of other countries of Eastern Europe. I still feel very Soviet, very Russian, and very Soviet Jewish. Actually, the more I live in the US the more I feel as an internal battle ground of multiple sometimes conflicting and sometimes complementary diaspora-nationalisms. In my case, I feel I belong to the Russian diaspora, the post-Soviet diaspora, the Soviet Jewish diaspora, and to the Queer diaspora.

How is the West seen today in Russia (or largely in the so-called “east”)?

It’s easier for me to speak of Russia for its context I know better. I think in Russia, the view of the West is very fragmented and is divided along political or ideological lines. The pro-democracy liberal wing in Russia has always been pro-Western and has been very consistent at that. But then, there is a nationalist wing and the Left, which are consistently take the anti-Western stance. So it’s a mix.

I feel our reality is seen as something exotic in the West, how do you deal with the question of difference?

Well, for sure for an every-day American person, and often even for a member of the art world in New York, Eastern Europe in a strange big exotic blind spot at best. And in the worst case, an accumulation of stereotypes derived from the Hollywood movies and American Cold-War era propaganda.

I guess, my approach is a slow and patient work of showcasing the complexities, in this case, of the Soviet experience, trying to convey the multiple dimensions, the multiple layers of that experience. So, I guess it’s about patience and offering education.

Among your subjects, communism is very present. What is your position toward communism?

I like the theorist Svetlana Boym’s distinction between restorative and reflective nostalgia that she makes in her book “The Future of Nostalgia”. The restorative nostalgia that is being practiced by conservatives and nationalists around the world is designed to take us back to the mythical lost past, where everything was wonderful and life was easy and good. The reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, does not attempt to promise a return to lost paradise, but instead it uses history as a tool of critique of the ugly features of our present. In that sense, I’m reflectively nostalgic for Communistm. It’s the progressive nostalgia, to use curator Victor Misiano’s term. It’s about being nostalgic for the idea of social justice and economic security, even if in reality these were only ideas and promises of the Soviet system and not the actually realized practices.

How is communism seen in post-soviet culture?

I think it’s very fragmented. On the one hand, there are now large populations of middle-aged and retirement-age people who didn’t accept the fall of the Soviet Union and who suffered tremendously as a result of the free market “shock therapy,” especially in the 1990s. I’m talking about the collapse of industrial production, inflation, and severe poverty.

There are also a large population of younger people who are also disillusioned with the prospects of social mobility in the new Russian society.

There is also a vibrant post-Soviet Left, especially among the millennials, including in artistic and cultural circles, who adhere to Communism and whose belief system was formed already in the post-Soviet era, after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

You have a research-based practice. Which are your favorite topics?

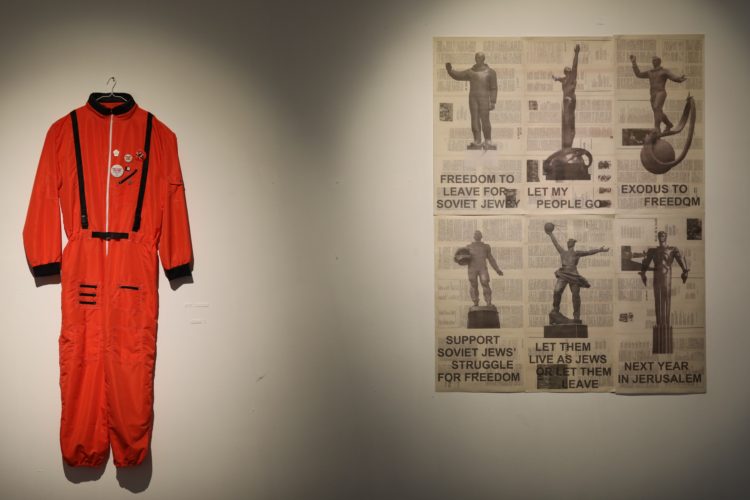

My work in 2000s was mostly made from a universalist position of a generic post-Soviet artist, who doesn’t have any particular ethnic or gender identity or sexual orientation. For example, I did a number of projects about the history and repression of the American Communist movement in the 20th century as part of the grand narrative or the 20th century radicalism. I viewed American Communists as dissidents who envisioned a different America, an America without class divisions and exploitation.

But then, in 2010s my work has changed and I started doing projects that would complicate the narrative of Soviet history or American-Soviet relations and these projects were also connected to my personal identities as a gay man and an Eastern European Jew. But I remained within my larger post-Soviet project, talking specifically about Soviet Jewish identity and Soviet LGBT histories.

I am interested to know more about your queer projects. I imagine making queer culture in Russia today is sort of a war, am I wrong?

People do it and queer culture has been developing over the last decade in Russia full speed, more than in the previous twenty years, I think. But, of course, many queer activists and artists get into a lot of trouble with the government as well. It goes hand in hand.

Most of my queer work was made in New York, so I’ve actually never been censored for my queer work in Russia. But on the other hand, I haven’t been getting many invites to show my queer art in Russia. I think the only time I showed my queer-themed work in Russia was in 2013 and it went fine. But it was a large group exhibition at a private museum, so it was easier to blend in and fly under the radar.

Interestingly enough, I get more invitations to show my Jewish-themed worked in Russia than queer-themed. I think it’s interesting because 30-40 years ago, I think, it would’ve been difficult to show Jewish-themed work in Moscow. So, times change and it makes me feel optimistic.

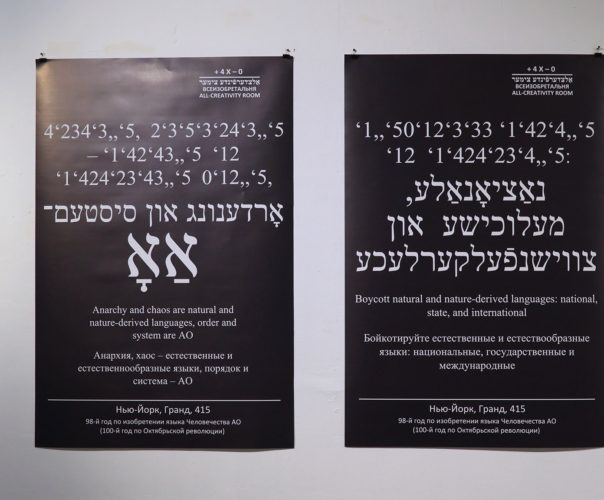

I am intrigued seeing you speak about Yiddish culture, not Jewish culture. Why? Is Yiddish language still alive in Russia today?

I’m speaking of Yiddish culture as opposed to Jewish culture to refer to a more open conception of new Yiddish culture that is not necessarily ethnicity or religion-centric. The new Yiddish culture, at least the way it’s developed since the 1970s, is welcoming of not only Jewish but also non-Jewish creators and practitioners. So it’s a post-vernacular culture, a culture created by people who often learned the Yiddish language from scratch and who come from different backgrounds and walks of life. The focus here is on the language, culture, and history, as opposed to on the power of authenticity that derives from the identity one is born into.

Speaking of Russia, sadly, Yiddish is not spoken as much in Russia today since the older generation for whom it was the mother tongue has passed. The silence of Yiddish in Russia has to do both with the result of the Holocaust and also of the state-sponsored assimilation program for Soviet Jewry, where all formal elementary and secondary schools were classes where conducted in Yiddish were closed down in the 1940s and never revived.

What is your connection with Yiddish language? Did you grow up linked with this language?

Yes, all four of my grandparents were Jews and native Yiddish speakers and spoke Yiddish at home. They all spoke Russian as their second language and would often make grammar mistakes in Russian. All of my grandparents came to Moscow form Ukraine right before the War and my parents were born already in Moscow. I was particular close to my grandparents from my mother’s side and I vividly remember them speaking only Yiddish between themselves and they would only switched to Russian to talk to us grandkids or to my parents. So Yiddish was very much alive and well in our household till 1978 when my grandfather died. Then, in around 1982 I asked my grandmother to teach me Yiddish, to my father’s dismay who felt that it was a waste of time and not a very practical thing to do for a Soviet boy of the 1980s. But my grandmother did teach me some Yiddish during that summer, although we didn’t get very far. But then after coming to New York, I took some formal Yiddish classes there.

Before reading your manifesto I was living with the impression Yiddish is dead and buried in Eastern Europe: am I wrong?

No, Yiddish is alive. There is a very large Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jewish population in the US, UK, and Israel. And there is a vibrant secular New Yiddish culture movement happening around the world, mostly in music and theater. They are the Yiddishists who are fighting for the continuation of Yiddish as a medium of cultural production, but most importantly as an everyday spoken language.

It’s true that the numbers of Yiddish speakers, especially of secular Jewish native speakers, remain small as compared to the pre-War numbers. Of course, most of the Yiddish speakers of Eastern Europe were murdered in the Holocaust. But Yiddish never stopped. It has migrated and changed. It’s a living language. It’s very stubborn and is determined to stay alive.

POSTED BY

Valentina Iancu

Valentina Iancu (b. 1985) is a writer with studies in art history and image theory. Her practice is hybrid, research-based, divided between editorial, educational, curatorial or management activities ...

Comments are closed here.