As was to be expected, perhaps, this year’s edition of the Art Encounters biennial was marked by uncertainty, by the vicissitudes of the extended global pandemic and the local measures that, necessarily, affect our day-to-day lives. The week prior to the biennial’s opening I took part in a viewing of Bucharest-based artist Traian Cherecheș’s work made for the exhibition Secret Wing, an audio-video installation that intoned, with the sufi-/effi-ciency and machine-like quality of an AI, Exit – Existence – Extinction, which gave me the auditory hallucination of hearing the word Encounters at the end of each cycle. After that I became confident in the unfolding of what is perhaps the most important art event in Romania. Even though prior to the official opening it was still not known whether the biennial would be open to the general public, as the Timișoara authorities chaotically resorted to various kinds of restrictions, this year’s edition was finally opened, though with a substantially reduced attendance. Still, the biennial benefited from a more specialized audience, including representatives of local art galleries and institutions, as well as of international ones, among which perhaps most prominent figures were Bernard Blistène, an internationally renowned curator, who was until recently the director of the Centre Pompidou, Leontine Coelewij, curator at the Stedelijk Museum, and Susan Gloudemans, director of the Rijksakademie Amsterdam. In terms of galleries, I would also mention Marlene von Carnap, director of the London branch of the prestigious Michael Werner gallery (representing the Marcel Broodthaers and James Lee Byars estates), who talked in a television interview about her her surprise discovery of two artists at the biennial, namely Ioan Sbârciu and Traian Cherecheș. There was also the consistent presence of members of the diplomatic corps in Romania, among whom the Dutch ambassador Roelof van Ees and the honorary consuls of the Netherlands, who have taken it upon themselves to promote the Dutch artists and prestigious Dutch collections that gave the Secret Wing its substance.

From the biennial’s title, Our Other Us, to its central exhibitions, in a total of 9 spaces throughout the city—Kasia Redzisz’s How To Be Together, Mihnea Mircan’s project Landscape in a Convex Mirror (created under pandemic restrictions, completely remotely, but which, in terms of practice, functioned like one of the exhibition’s central themes), and Secret Wing, curated by Maria Rus Bojan and Bogdan Ghiu—all were based on the approximation of distance (and, more importantly, its practice) which the individual establishes between themselves and the outside during difficult, turbulent times. From withdrawing to containing and recomposing the macro within the micro, most often through utopias or personal mythologies, Pavlovianly or strategically generated. The first of these, ab origine means that humans are part of nature and cannot dissociate from it except artificially and illusorily; the second refers to the diversity of cultural manifestations as source of the entire work of humanism and, implicitly, of progress.

I will talk about the exhibition about which Maria Rus Bojan – one of its curators – said that it was constructed like an ample collective poem, each line representing the universe of one artist distributed windingly into niches, perhaps a similar structure to the labyrinth on the cover of Mariana Marin’s poetry book from 1986 which gives the title of the exhibition. A poem of memory’s withdrawal but also of the symbolic fortifications emerging from difficult (to put it euphemistically), syncopated contexts, sometimes having the inevitable collective history (totalitarian regimes) as their source or with ramified and somewhat imminent implications (the pandemic or environmental catastrophes). A confessional poem in blank verse, to be recited in the cavernous insides of the Art Museum or in its well-lit niches – but never in the middle – the exhibition describes, Homerically but not hyperbolically, the beginning seemingly detached from the factual but intangible history of what we universally accept as defining for the phrase our times, which became fixed with the end of the sixties. A period about which Michel Houellebecq calls the third great mutation, as a consequence of secularization and labor movements. An era of scientific positivism, focused on fortifying the individual self and its dislocation from the moral or even natural order, employed within the wake of countercultural movements, increasingly embodied and tangible in the present thanks to the hyperconnectivity of communication networks.

The corpus of artist selected for the exhibition seems to combat the structure of political systems, denouncing the crisis of global social solutions by means of an aesthetics that often affects a resignification of the everyday – a clear examples is the series Monthly Evaluations of the late Ioana Nemeș, one of multiple tragic fates in the exhibition – by recovering the unusual from the daily cyclical grind, of the small, invasive mechanical acts situated on the fluid border between the individual and the social. Not even outstretched hands, not even cries for help. Often these practices consist in creating their own language of signs, either recovered from the history of the medium and reinterpreted, sometimes based on constructed mythologies, other times based on immutable, recovered ones that are translated in a postmodern style. Transition or transgression, depending on our chosen value system, creates a vocabulary of desire rooted in the illusory individualism of typically modern movements. But deliberate estrangement seems to also manifest a conscious and infinite feeling of the tragic, an awareness about which Lévi-Strauss said: “The one real calamity, the one fatal flaw which can afflict a group of men and prevent them from fulfillment is to be alone.” It is often the poetry of individuals whose artistic information comes from constant personal reflection rather than sensationalist news, magazines, films, or sources of social spectacle. Besides these superficial quotes, the individual elements are translated into visions with the ethereal consistency of a dream, with an open, associative structure.

Because of its placement within the museum, from its basement and innards to the well-lit rooms on the upper floors, the exhibition can be compared to an archaeological dig, one that tackles liminal spaces between reality and its representation, between real and experienced, imagined and remembered. This glissando between reality, representation, and signification outlines a fertile ground that generates both the emotion of unstable uncertainties as well as a rich plurality of meaning like modernist incunabula about the archaeology of the individual.

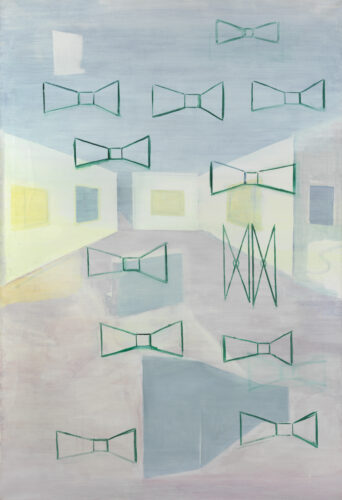

Atypical for the so-called jeans generation, the ethical mantras of poet Mariana Marin transpire repeatedly, like delimiting through a shell, creating a new functional system insulated from the general political one. Singularly, the work that embodies these themes of withdrawal and regeneration, in terms of iconography, a work which was chosen for the poster, namely La maison, created in 1986, the same year as the Romanian writer’s book, is a painting done by René Daniëls, himself having succumbed to a tragic fate. Daniëls applies, in what he called “sweet wrappings,” a white transparent layer overlapping the image, as if your vision were filtered through gauze or colored glasses. This fog offers depth to the background, returning space to its rightful owner, so to say. Floating in the background are Daniëls’s famous bowtie motives, wall structures of the exhibition space rendered diagramatically.

The lines by Mariana Marin that I chose as the title of this review illustrate, I believe, the success of Maria Rus Bojan and Bogdan Ghiu’s curatorial endeavor of recovery, in which they placed themselves deliberately on the side of the minority, which became historically cut off the moment everyone seemed determined to place themselves on the side of the majority. I think that what this exhibition can teach us is that, looking towards diversity, we should not only promote the survival of those micro-cultures that western civilization has not already wiped out, but also to encourage the birth and growth of a new age of particulars.

Secret Wing

Artists: Lucas Arruda, Vlad Basarab, Ion Bitzan (1924-1997), Kasper Bosmans, Alin Bozbiciu, Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976), Cornel Brudașcu, James Lee Byars (1932-1997), Sophie Calle, Simion Cernica, Traian Cherecheș, Yahon Chang, René Daniëls, Marlène Dumas, Constantin Flondor, Octav Grigorescu (1933-1987), Johannes Heldén, Peter Jecza (1939-2009), Anselm Kiefer, Sigalit Landau, Gherasim Luca (1913-1994), Lucassen, Ioan Aurel Mureșan, Ioana Nemeș (1979-2011), Iulia Nistor, David Robilliard (1952-1988), Viviane Sassen, Ioan Sbârciu, Kathrin Schlegel, Mladen Stilinović (1947-2016), Nora Turato, Ulay (1943-2020).

Curators: Maria Rus Bojan, Bogdan Ghiu

Location: The Timișoara Art Museum, Piața Unirii nr. 1, Timișoara

Visiting period: 1 October – 7 November, 2021

With works borrowed from the following collections: Defares Art Collection: Eckard; Matthijs Erdman; Paul van Esch; Ferri de Boer; akmo; Janneke and Marc Dreesman; Muzeul Național de Artă Timișoara; Col. Ovidiu Șandor; Galeria Plan B; Anca and Darius Nath; Dr. Sorin Costina; Jecza Museum; the Francise Chang collection; the Dr. Aeneas Bastian collection; Estate Ion Bitzan.

Organizers: the Triade Foundation and the Timișoara Art Museum in partnership with the Art Encounters Foundation, AFCN, Centrul de Proiecte al Primăriei Timișoara, European ArtEast Foundation London and the Consulate of the Netherlands in Romania. Sponsors: Grup Transilvae, Fundația LC, Galeria Plan B, and MB Art Agency Amsterdam.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.