David Schwartz is a theater director, he lives and works in Bucharest. He is interested in performing recent histories, in subjective histories of the post-socialist transition, and in art as a way of political emancipation. He works on political theater projects that involve: miners and other worker communities; institutionalized elders; refugees. He is the co-founder of Gazeta de Artă Politică.

In your last shows, the director, from the canonical point of view, is missing. Is there no need for a director anymore? Did you change your way of working?

In our last shows it was very important for us to make it clear that not just the director, nor the director-playwright team, is the author of the show, but that the plays have a collective author that equally captures the perspectives and ideas of all those involved in the project. Beyond this general aspect, there were some specific reasons for the “missing director”, all of which were closely related to the working methods for each show. “Moldova independentă. Erată”[1] (“Free Moldova. Erratum”), a show we did at Teatru-Spălătorie in Chișinău about transition and Moldavian contemporary history, was put together with the help of local artists. I was the only Romanian. We made the text together, we had the same perspective and we talked about it a lot during our work process, but the vision of the history of Moldova and the direct experience is theirs first and foremost, my role was to ask questions, clarify some aspects, see things from the outside and put everything into context. The last thing I wanted was to share my opinion about Moldova, especially since in Romania, this kind of condescending attitude is a common habit. We, Romanians, always know what’s best for the people in Moldova. So we thought it was natural, according to our work methods, but also from a strategic point of view, to sign off on this show together.

With “Voi n-aţi văzut nimic!”[2] (“You Didn’t See Anything!”) it was a wholly different situation. It is a project, a route that involves research, initiated by Alexandru Fifrea, an actor and playwright, a mixture of documentary-theater and personal history. The boundaries between the position of director-playwright-actor are harder to pinpoint, we worked together on the text and the editing, and our roles, in terms of artistic decisions, were equal.

So the boundaries were naturally set as you went along?

Precisely. It wasn’t my from now on I won’t be the director project, things evolved towards that, they changed each time, and with “What We Could Be If We Knew”, our latest show, it was sort of the same situation: a project that began with a lot of our ideas and research, that myself and the artistic team put together. It was important to promote it as a group effort. On the other hand, “What We Could Be If We Knew” is a very direct political show and we are aware of that. It puts forward an ideological perspective on the future from the resistance’s point of view, an ideological perspective on protest movements and the relationship with recent history. We, the team, believe in these things and it was important for us that we sign off on the show together. The work process, just like before, was a collective one.

All of these aspects don’t affect the director’s contribution. It isn’t about the “missing” director – directing, from making and following a unitary concept for the show, to harmonizing the various components (art direction, music, etc), to coordinating rehearsals and working with actors, is still something that needs to be done and something that I, as well as the rest of the team, partly own up to. What actually changes is the perception of the director-as-author-of-the-show. Directing is just part of working within a group and it is just as important as any other job, and the shows represents everyone’s perspective and point of view. This is why it is rather upsetting to read in articles and reviews about “director David Schwartz” who did this and that… and when “he enormously hears and monstrously sees”, and when he has “a special type of sens of humor”, and when “he (and him alone) is preoccupied with left-wing subjects”, and when he mixes too many ideas in the same show, it is always about the director-author. Unfortunately, a big part of the criticism and the local cultural press doesn’t seem to understand and accept the process of working within a group, shows we own up to and built together, where everyone gets to contribute, including with the concept and vision. Whereas this aspect is detrimental to the kind of theater that we make. The fact that most press interviews are with me, or with Mihaela Michailov at times, is telling for this situation. Team G.A.P. had to conduct, most of the times, interviews with the actors of our shows as well.

How were the tasks split when working on “What we could be if we know”? Are there any coordinators in a collective work process?

At first, the research work was split equally between us. We chose various themes, we decided on the subjects we were about to research together and what we wanted to say in the show. Researching also involved archive, press work and looking into the documents belonging to the repressive side, as well as literature, memoirs and personal interviews. The actors, the scenographer, the playwright, we all worked together side by side. The documentation process was coordinated by Marius Bogdan Tudor and Ionuţ Sociu. Then we all worked on building the script. Writing the text was also a collective task, where everyone came up with scenes, directions and editing suggestions, helping with the texts that others wrote.

What is the relationship with the archive documents?

The show is 100% based on preexisting material that we combined, edited, reinterpreted. I am talking about the archives and documents belonging to the Securitate, trial transcripts, various news clippings and texts that are over 80-90 years old. Naturally, putting on the show is a process of fictionalizing these materials.

Is there any historical accuracy to the show?

Yes. There clearly is historical accuracy, we did not make anything up, we did not change dates or situations. We took everything from the archives and, when it was possible, from personal interviews. Of course, there is a degree of fictionalizing, some of the material has been edited, shortened, was taken out or was condensed. For example, during the military trial for the ones who beat up the strike leaders of 1918, there were more soldiers involved, but we reduced the number to just two. There are some small changes of this sort and we think it does not affect the historical perspective, it is just an adaptation to give it a show format. The historical accuracy was very important when it came to the data presented. There is a lot of data, lots of numbers and economical and historical info in the show, both in the Arimania [4] part, as well as within the fragments. They were all gathered from historical research papers, economic history papers, etc.

The presence of utopia heightens the dramatic feeling of the historical past and it also gives meaning to these fights. Why do you use the future tense?

We thought it was important to present an egalitarian version of what a possible socialist society might look like. On one hand, as a strategy for explicitly owning up to an ideology, on the other, to distance ourselves from rudimentary anti-communism, where “communism” is the same as a dictatorship. Utopia has to be seen as a doable possibility and as an incentive to built a better and more righteous society. As Veronica Lazăr recently said in an article [available only in Romanian], we should not forget the fact that universal voting for women, freeing the slaves and the 8 hour work day were, at one point, considered utopias, dreams apparently impossible to accomplish. That being said, even though the fight for these rights is far from over, they are attainable and part of any progressive political agenda.

In 2014 there was a movie, “The Giver” (I don’t know if you’ve seen it), that purposed an egalitarian utopia, a perfect society with no pain, suffering, or wars. This entire community is represented in black and white – that suggests the fact that this ideal utopian society cancels out the individual, it castrates their emotions and does not allow a real personal development. The Ahriman costumes are grey.

An egalitarian utopia, of which many of us, the ones that worked on the show, think that it would be a step forward for the well-being of a great number of people in the world, implies rules that have been very well set, owned up to and respected. I think that a system that works based on equality and cooperation, that is fair for as many people as possible needs rules that, of course, should not be hierarchically imposed, but rather constantly debated and improved, with a wide contribution. As such, we did not want to present a naive utopia in which we see some hippie Ahrimen that have fun all day, smoke weed and tell us that everything is cool and OK – you don’t need to work, you don’t need to do anything, every problem takes care of itself. We wanted to present a version where the Ahrimen are workers as well, who love and work together as a team, where the collective is the most important. During rehearsals, we talked a lot, among ourselves, about the relationship between self-imposed rules that are followed by the whole group and individual freedom and how these things are negotiated. It is important to think about the limits of individual freedom in a world where everyone’s rights and necessities are being taken care of as much as possible.

We did not want to built a hyper-relaxed and hyper-naive future where, no-one-knows-how, all of humanity’s problems are solved. We really questioned how this society could function and I think it could work with definite rules that everyone owns up to and everyone considers to be working in everyone’s advantage. This is why we chose the uniforms, in order to built an Ahriman work collective, where working-actors work in teams, synchronize and help each other out.

Earlier you mentioned that the show is ideologically owned up to, a group ideology that you do not name.

We set out to capture the history of Romanian protest from 1918 to 2000. Within these temporal limits, we are looking for the general perspective of the workers, of those who formed the protests and resistance, not the perspective of those who wanted to kill these movements. This is, of course, a left-wing vision of historical trials where what mattered were the groups and individuals who fought for our rights, who challenged, from an egalitarian perspective, the beginnings of the capitalist system, and the opposed the various forms of fascist dictatorship. But this is also the case for the workers who had a communist point of view during the socialist period and criticized the fact that the system is not really communist because it is based on a hierarchy and exploiting workers. For the period after 1990, we return to a type of interwar version where resistance movements must confront themselves with an unregulated capitalism, where the imposed foreign neoliberal economic order is the political dominant.

“What We Could Be If We Knew” is the most aesthetic show, which might emotionally empower the spectator. What does the show’s aesthetic mean for you?

This is a very interesting discussion that deserves more space, especially since a lot has been written lately about the role of aesthetics in political art and the various forms of “formal revolution”. In short, I’d say that the Dadaist dictum “aesthetics is compressed ethics” is representative for our team and we work based on this saying. You want to send out a message, a perspective on an event, a context, a situation, etc. This is where you start to look for the best and most coherent formal solutions for representing said perspective/situation. Depending on how strong the emotional as well intellectual impact is on the spectator, we think that our aesthetic choices were suitable. Of course, this discussion is a lot more complex, there is much to say about the democratization of the show, about the type of participation the audience can offer within a show, and i think that there is still a lot more room for searching and experimenting.

Minimal realism, or 3 chairs – 3 actors – 1 projector, has become a repetitive scheme, an almost boring cliché of contemporary theater.

I think that this minimalist aesthetic offers a rather big artistic challenge. How and how much can one convey with the maximum economy of means? On the other hand, the option for minimalism is a reaction to the sometimes revolting opulence of state theaters, where huge amounts of public money are spent on shows that are performed only a few times. I think this is also an ethical dilemma – for me it is important to have a certain restraint when it comes to the budget for decor and costumes. This is also a reaction to a type of aesthetic show where the concept, content, message are completely diluted. Of course, this aesthetics is sometimes related to various material or logistical constraints. When you’re working with small budgets and alternative scenes without great lighting or sound systems, you automatically restrict as much as possible and build things this way. All in all, sometimes it’s about adapting the show to the environment and the conditions in which it is produced and performed. For example, with “SubPământ”[5] (“UnderGround”) we set out to make a show that is easy to move and adapt. With our own lights, music with no amps, no sound system. Our stake was to perform the show in the cultural centers and schools of mining towns, knowing that it was possible that these spaces might not have the right technical setup. So we thought of a show that can be easily performed anywhere, even in a school classroom.

Can the historical fragments you chose be seen as a subjective left-wing history? I want to know if there is more to this besides documenting and performing these protest.

It has been said about this show that it is a history of communism or the Romanian left-wing. We never intended this. A history of the Romanian left-wing should probably start with Bălcescu. This type of history is such an ample subject that it is hard to believe that it can be represented in all its complexity even in a book with thousands of pages. Our show had a more modest purpose, although still ambitious: the history of protests and anti-system revolts post 1918 from a left-wing perspective, focusing on unions. We did not intend to write a complex, comprehensive history, but rather to shed some light on certain episodes that might make the viewer want to do his own research, find out more and bring a new perspective in understanding local history. One important aspect was to eliminate the auto-colonial deeply rooted belief, in Romania as well as in other Eastern European areas, that there weren’t any real protests or resistance movements and that the Romanian people are soft and passive. Historically, things weren’t like that – and we think there is much need for narratives that offer a different point of view.

How many people took part in the protests you illustrated? I am wondering how large is the collective character. Is the number representative for society? Are these people visible?

It depends on the situation. In 1918, over 100 people were harmed and killed and there were around 800-1000 strikers. In other situations, like the general strike of 1920, tens of thousands of workers from all over the country, from every field, including public clerks and the military, were involved. It was a strike of huge proportions. During the interwar period, there were numerous strikes with all kinds of workers involved.

On the other hand, the idea is not to calculate the percentage of people that revolt, but to use these examples and learn from them. Especially since, most of the time, these fights brought about obtaining a lot of important rights. It’s about recovering certain historical episodes and offering a different take on historical figures and movements. The idea is to built an alternative history that gives people something to think about.

I don’t know if our discourse will ever become official, and it remains to be seen if we’ll ever make it in the history books… The socialist state tried to use a similar model, but it was taken over rudimentary in a Roller version, in order to return to Burebista and his succession of “great leaders” during the 1980s.

But I think it is important to build these breaches within the public discourse, for an alternative discourse of history to resurface. This is the focus of our show. Certainly not a history of communism, much less a history of Romanian communism seen from the Marxist-orthodox perspective, as other wrote about it.

Yes indeed, the article written by Iulia Popovici [available only in Romanian] postulates a number of untruths. Hope you’ve read it by now. Not sure if you’ll write a reply, just asking if you want to jump in right now.

I’ve read it and I think there are multiple aspects which definitely deserve a closer look. One of them is that the article operates with a typical method of false argumentation – firstly, it postulates that the play purposes a history of the Romanian political left-wing, and secondly, it criticizes that this left-wing history is neither complex nor rigorous enough. This is the first catch, the article is missing the play’s main point. Another weird thing, the article criticizes the mixing of anti-discrimination and the struggle of women as concepts that do not conform to the Marxist philosophy. But including the history of resistance movements, even when they were illegal, within Orthodox Marxism has no historical basis. Romanian socialist and communist movements have been quite various, opinionated and eclectic. Like today, all kinds of conflicts, confrontations, ideological divergence arose. Even when it came to the illegal communist movement who’s ideology was guided by Comintern, there was a fluctuation and a diverse policy where modernization and industrialization were priorities. Thus, in the prewar communist movements, equal rights for women and men, illiteracy issues and fair rights for women workers were quite relevant. All of these taken into account, it was very important for us to highlight women’s roles in the resistance movements, including the fact that we wanted to challenge the cliche image of the reactionary man. To a higher degree, ethnic autonomy and the fight against ethnic/racial discrimination were central to the communist agenda. During the war especially, one of the main goals of communism was to fight fascism. Stopping Jewish executions was a huge and central focus for the party, with some of the members even organizing protection groups for the Jewish population. This was not by any means a secondary cause, an added extra to the class struggle. Besides, persecutions were also common – the authorities built labor camps for both political prisoners and for ethnic minorities (Jewish and Roma communities) as well, peaking with the Vapniarca and Rîbnița prisons that were especially built for Jewish communists. Basically, you simply cannot write a history of the illegal acts during the war without mentioning anti-fascism and ethnic persecutions. Another important aspect of the article is related to aesthetics, but unfortunately it operates with simplifications and omissions. It’s important to question why a play has to be Brecht-like all the way and what Brecht-like means all together. It’s hard to believe Brecht himself was “a-consequent-Brechtian-all-the-way”. From my perspective, detaching oneself from Brechtian inspiration works best in counterpoint with realist scenes, scenes with a huge emotional charge. What we’ve tried to do in many of our latest shows was to combine a realist type of play with various moments/fragments/means of detachment and rejection from and of any convention. Of course, time will tell as to what degree this strategy was a success. In the play “What We Could Be If We Knew”, using the Ahriman frame, we wanted to build autonomous scenes, containing different play conventions, from expressionist or Brecht-like scenes, to documentary realism or agit-prop. Basically, we tried to build episodes that are always based on the characteristics of the dramatized documentary material and the necessities of the messages/ideas we wanted to convey and discuss. Again, we can debate whether this strategy works, it is also something highly subjective. In the end I think it’s necessary to look at the various forms of propaganda theater – from Brecht to Meyerhold to agit-prop – as if they were tools which await the politically engaged artist, tools which can be used in a wide variety of contexts, but that shouldn’t be totally or exclusively used, no is it mandatory to use them. But in no way do these tools exclude the use of various realist theater forms, including any kind of combinations. But I agree with Iulia Popovici’s article, I too would’ve enjoyed to see more agit-prop in the works.

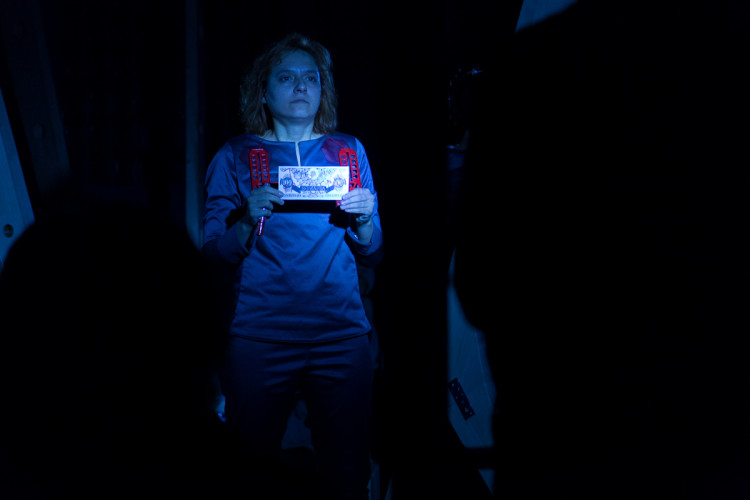

“What We Could Be If We Knew”

By: Mădălina Brândușe, Paul Dunca, Adela Iacoban, Alice Monica Marinescu, Mihaela Michailov, Katia Pascariu, Alex Potocean, Cătălin Rulea, David Schwartz, Ionuț Sociu, Andrei Șerban, Marius-Bogdan Tudor.

Centrul de Teatru Educațional Replika, 2015 (as part of the Platform for Political Theater 2015, a project that is financed by a grant from Island, Norway, Liechtenstein and the Romanian Government).

[1] “Independent Moldova. Erratum” (Teatru-Spălătorie 2013, a show by: Ion Borș, David Schwartz, Dumitru Stegărescu, Doriana Talmazan, Irina Vacarciuc)

[2] “You Didn’t See Anything” (Salonul de proiecte 2015, a show by Alex Fifea, Cătălin Rulea, David Schwartz)

[3] “We Weren’t Born in the Right Place” (2013, by Alice Monica Marinescu and David Schwartz, with: Alex Fifea, Katia Pascariu, Mihaela Rădescu, Andrei Șerban, Silviana Vișan).

[4] A utopia written by the left-wing activist I. Neagu-Negulescu, that inspired the framework for the show “What We Could Be If We Knew” (“Arimania or, the Land of Good Understanding” / “Arimania sau țara bunei înțelegeri”, Brăila, 1923)

[5] “UnderGround”, a show about the life and the state of mining communities in post-socialism (2012, by Mihaela Michailov and David Schwartz, with: Alice Monica Marinescu, Katia Pascariu, Alex Potocean, Andrei Șerban)

POSTED BY

Valentina Iancu

Valentina Iancu (b. 1985) is a writer with studies in art history and image theory. Her practice is hybrid, research-based, divided between editorial, educational, curatorial or management activities ...

Comments are closed here.