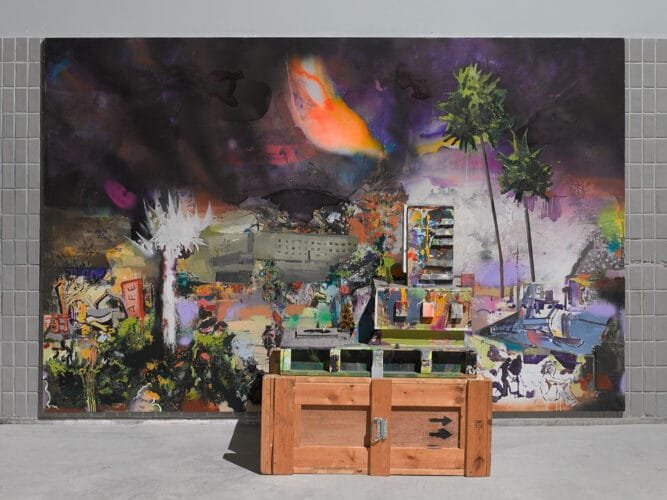

The following text, written to accompany Marius Bercea’s latest solo exhibition —one in which the painter explores & exploits, more than ever before, the possibilities of object making and installation in dialogue with painting— aims to clarify why, despite the inflation of these volumetric artefacts, we are still dealing with a painting exhibition. A total one for that. A painting-as-study exhibition, if we consider anachronistic terms, or expanded painting, if we use the contemporary glossary. In this regard, for instance, in a 2014 interview[1], Marius Bercea bluntly stated that his practice is “a kind of choreography of painting.” In this exhibition, the expression seems to be completed quite literally by a scenography of painting.

Today, when much of what we still ambiguously define under the label of “contemporary” the artistic practice appears to float free of historical determination, conceptual definition, self-referentiality, and critical judgment, Bercea stitches together—by looking back and across his own works— a dialogue about the illusory qualities contained within the flat painted surface, and through this the fundamental distinction figure–background, essential to Western painting since the discovery of perspective rendering.

On n’y voit rien, the title chosen for this brief review, references a book—somewhat sensationalist, written by art historian Daniel Arasse, which illustrates something central to the artist’s entire oeuvre. It’s about the way in which Bercea’s compositions reveal themselves iconographically, in a manner similar to those of the classical era, by leaving clues in seemingly insignificant or banal details. Be it domestic objects like the ubiquitous curtains filled with clairvoyant peacock eyes, the cloths with zoomorphic motifs referencing moralistic fables, or the symbolic wind passing through Californian fretwork walls.

At other times, the references are harder to access for those outside a specifically defined cultural area. I’m thinking here of the wooden refrigerator, painted on the front, containing only milk and eggs—as we can see through the alarmingly open door in the installation “As I walked out one evening. After a poem by W.H. Auden” (2025). This piece alludes to a very particular context: the shortage of meat in the years before the fall of the Iron Curtain.

At the same time, by adopting this title, the text also highlights another recurring feature in Bercea’s work: his generous engagement with literary sources that infuse his artistic practice. In this case, together with curator Tevž Logar, the artist reinterprets the title of a well-known play by Eugène Ionesco, New Tenant, to which he adds the grunge-chic phrase, Sunshine Noir. Sunshine Noir being a reference to a neo-noir sub-genre, a reverse neo-noir in fact, spectral, solar and superficial.

In Ionesco’s absurdist play, strikingly relevant today, he addresses the overwhelming accumulation of objects, the compulsive hoarding of furniture during when decorating the apartment, which becomes increasingly smaller as a result. This, categorically evokes the theatrical props in the installations on view, but more broadly, it refers to a state of “scenographic suffocation” that Marius Bercea also explored in his previous solo exhibition “This Side of Paradise” (2024), curated by Diana Marincu. There, the confined and claustrophobic space of the Art Encounters Foundation was filled with immense canvases that appeared, at least visually, impossible to fit through the narrow staircases and door frames.

As in a true 17th-century painting, in Bercea’s works it is life itself that we deal with—not life in the abstract, vitalist sense, but biographical, everyday life as we all know it—that surfaces. Whether we’re talking about clothing patterns borrowed from the creations of his wife, the designer Smaranda Almășan, whose studio is just across his, or about his students from the University of Art and Design (UAD), who appear individually or in groups in most of his portraits since 2019; or, whether we refer to objects such as the iconic H&M sweaters or skateboards, now repurposed as yet another support for imagery—precisely because his eldest son practices the sport professionally—all of these elements come together in a process that proves painting and the act of authorship, cannot be separated from life. Art can truly be a mirror of reality—an approach that differs from social and participatory art practices, which take an interventionist, rather than observational, stance toward the immediate. And the mirror is all the more powerful the clearer it is. This is, if you will, something anti-modernist in spirit, yet something that seems to transform the painterly substance almost in a molecular way through its disarming directness, as breaking the fourth wall, the boundary between stage and real world. Yet, just like in the aforementioned era, the downside for this approach is that unless you’re familiar with the characters, literary references, architectural and fashion tropes, the interest will not pass the aesthetic perception.

Even though mundane and precisely located, all these elements are caught in narratives that don’t depict real situations, but rather allegorical or staged ones. It’s like entering a garden of forking paths. In this context, it’s worth observing how the titles of Bercea’s works, especially the portraits, do not refer to the subject represented, but are themselves allegorical. The narratives are intentionally obscured, eerie, featuring dystopian & dichotomous architectures that piece together third-order narratives from fragments of the real ones. The artist expands the subject beyond mere quotation of mass cultural and media iconography, directing it toward a new focus on social and architectural spaces.

Atmospherically, the viewer experiences a post-historical sentiment, triggered by a blend that juxtaposes compositionally congruent elements—as if in a museum displaying a collection of disparate narratives, thus positioning the gaze at the end of history, in a point that allows for retrospective reflection.

Just as his painterly style has shifted—from a grunge, sexy-guttural materiality, where the abstract manner, dense like a nightfall, merely seemed to allow figurative glimpses to peek through, to a more refined, cohesive style with classicist overtones, so too have his characters evolved: from anonymous outlines toward individualized portrayals, almost exclusively of people from his circle.

The techniques of collage or fretwork that defines the characters in his current three-dimensional installations had already begun to appear in painted form in the works after 2010, where they resembled sticker-like cut-outs placed against phobic, abstract-expressionist backgrounds rendered using a variety of painterly techniques and accidents on canvas. Moreover, if you had visited the artist’s studio in recent years, you would have inevitably stumbled upon these cut-outs, used then as study props for painterly compositions. Their transition into a 3D diorama was just a natural next step for an artist with the curiosity and the generosity of Bercea.

All this auctorial plasticity referential to his own work and his own life—plasticity understood as the attribute of an initial substance to perpetually transform itself on contact with the environment, taking over but also remaining there, to the detriment of its sister, the elasticity, which only shows that a substance always returns to its initial form—also outlines the fresh approach of these diorama-scenographic installations which are three-dimensional renderings of paintings. The work that gives the exhibition its title, New Tenant, Sunshine Noir, is a 3D recreation of the painting Offspring of Neptune (2023), while Classic Aroma Stabilizer (2017) is the painting that forms the basis of the second installation—the one mentioned earlier with the open refrigerator door. While the first is clearly labeled as an installation in the exhibition layout, the second is catalogued as a lightbox. It is also a reference to the box with unidirectional lightning used by Baroque painters and, much later, by Corneliu Baba, a Romanian artist whom Bercea actually collects.

As for the source & type of image making, many of Bercea’s works seem to draw increasingly on the historical relationship between painting and photography. If Bercea is attentive to painterly techniques like size-sight[2], famously used by John Singer Sargent, he also integrates methods borrowed from photography—especially the crop or the chosen format for paintings, reminiscent of 35 mm film or 4×5 medium format, a nearly square.

Similarly, the way he intensely inspects the textures and colors of his domestic life is expressed pictorially with both the skill of an abstract-expressionist painter and that of a photo-realist billboard artist, evoking the sunlit promises of California in passages of sumptuous illusionism.

It is true, when following Marius Bercea’s career since its beginnings in 2002–2004, that there’s a clear tendency toward expansion, both in terms of canvas size and in the ambition of his exhibition setups. And it is equally true that an artist of Dürer’s stature, for instance, often did not achieve the same level of intensity in large commissioned artworks as in his smaller ones, or in the watercolors. It is also true that all these instances—which stem less from mere societal observations and more from one of the most archaic human gestures, that of treating a surface with a substance in order to alter its appearance—carry within them inextricable traces of personal taste. Therefore, in the same spirit, I would like to believe—and I do believe—that all these courageous, expansive, total-approaches are the fruit of Bercea’s own artistic inquiry, rather than the result of simple market logic, for an artist whose international profile continues to grow.

Marius BERCEA: “New Tenant | Sunshine Noir” [Jecza Gallery @ Scanteia+, Bucharest, 17.05 – 12.07.2025]

[1] Cultura Magazine, 481-482, 21 August, 2014

[2] Size-sight method in painting involves positioning the artwork and the subject side by side, at the same distance from the artist, so that they appear the same size when viewed from a particular vantage point. This technique allows direct comparison of the subject and the painting, helping to achieve accurate proportions and shapes. Sargent perfected the technique, often sketching the sketch of the character with brushes fixed on sticks up to 2m long, so that he could sketch the defining features as they appear in a dimension consistent with a real-life one

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.