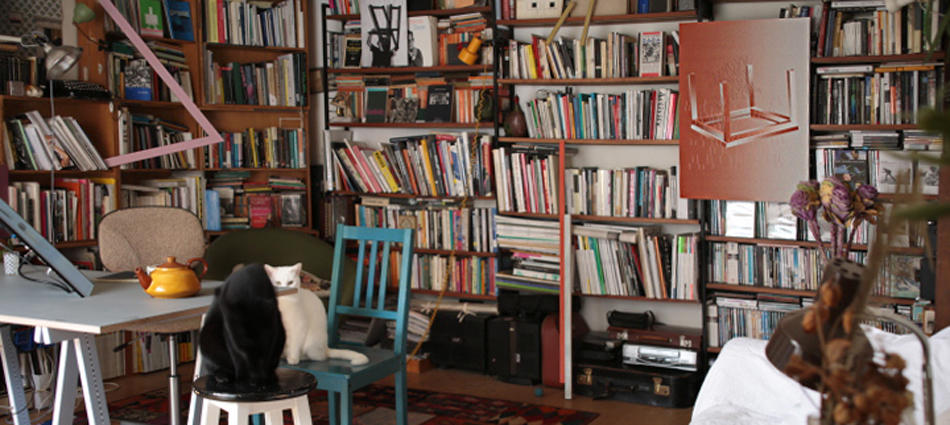

Letiția Călin is a Romanian artist who received her education at Goldsmith College in London. She has been living in South London for over 5 years, continuously accumulating objects in her one-bedroom flat. This fall, she turned the apartment into a very particular type of gallery. Cristina Bogdan talks to her about this original situation.

Why art in a flat? How is showing art in a flat different than in a public gallery?

Many artists have historically used their apartments to host exhibitions and share their work and ideas amongst friends which then became sites for collaboration and intimate social situations and which fuelled a lively art scene in the process. In my case the reason is manifold but it primarily came out of a desire to foster this kind of conviviality in relation to art and of course out of necessity as space is now the ultimate luxury in London. And I do think that hosting events in a private space imbues everything with an intimacy and honesty that is quite rare in the art world and I prefer it this way. I was offered at one point to host my film screenings in a public gallery but I decided against it as I think that a private domestic setting enables a more relaxed atmosphere while allowing for more meaningful relationships to form at the cost of having a wider audience.

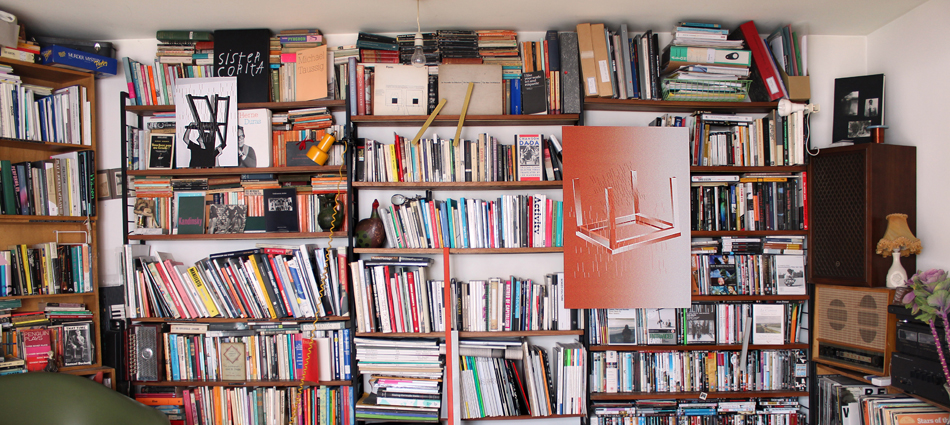

I should say that I did not set out to organise exhibitions in my flat from the beginning, particularly given that my flat is very small. For a few years the space was run as a semi-public gathering space for interested parties coalescing around shared interests and taking part in reading groups and film screenings where discussion and a spirit of communal learning was key. It was only recently that I decided to find out what hosting art works in my house would imply both for the house and the artworks. An important decision from the outset was to leave everything as it is and to not try to emulate the white cube of the gallery. Of course I leave it to each artist to decide what they might want moved or taken out temporarily but in general the idea is to work with the space as it is, not deny or camouflage its domesticity. And this is where the differences between showing art in a someone’s flat or in a gallery becomes evident. Conventionally, the traditional exhibition set-up with its bright white walls, quiet reverential mood and legitimising press releases is too often a prescribed environment with an overdetermined set of behaviours for encountering artworks and frankly I think that this model of the institutional white cube emulating the museum space and its self-historicising grandiosity is not always doing the art on display any favours. Conversely, one’s domestic ecology, with its messiness and manifest subjectivity allows for a more personal and dynamic encounter where new and unexpected conversations are allowed to take place and these inevitably rub off on to the artwork.

I always love going to someone’s house for the first time and seeing what things they choose to live amongst, the stuff they collect, the books they have, the colour of their sofa and other details of their domestic and decorative arrangements. It satisfies a voyeuristic curiosity and helps understand someone’s sets of references better. A lot of the stuff we choose to keep within our home can be considered trivial and inconsequential but at the same time the home is the place where most of what matters in people’s life takes place. The division between major and minor is important precisely because the consequences of the latter are often hidden and disregarded despite being just as significant. I like that this type of setting brings with it a widened and more porous system of valorising.

What is the program you are proposing for your gallery?

I decided to run the first few shows under a framework of friendship given that an artist run project-space’s audience is primarily made up of friends and friends of friends. The idea was to invite a friend and ask them to subsequently invite another friend who then in turn invites another and so forth, thereby setting in motion a chain reaction based on friendship. They would each be free to use the space as they wish and create as many works as they see fit. These solo shows would then be interrupted by a parallel series of group shows taking their theme and direction from the subject matter brought forward by the preceding solo show. Although for the next show I’m preparing something a little different. Additionally, each solo artist gets commissioned to create a small edition of a ‘useful’ object such as a design for a cup, a glass, a plate, a kitchen towel, a scarf, etc. Just another way of extending the art into the domestic sphere.

How did the domestic framework of the flat cohabit with the first show, A well-furnished room, and how did you decide on the first artist to invite?

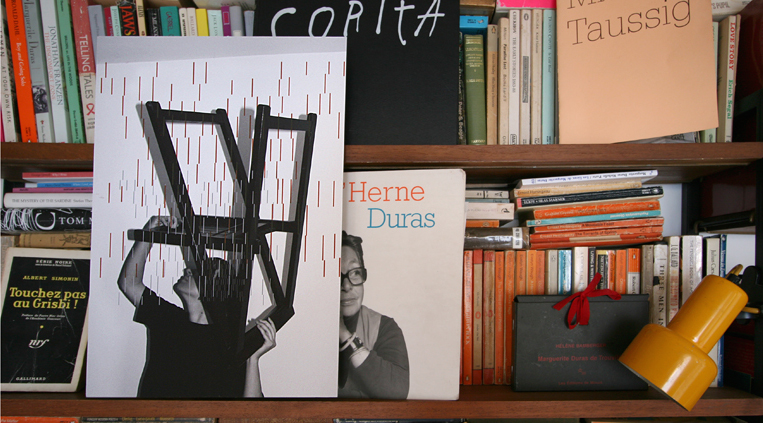

As I mentioned earlier, the domestic space with its middle-class coziness and conventionality sits in opposition to the traditional conditions for the display of art but also as subject matter, the domestic has been forever relegated, alongside the decorative and the handicraft, to the feminine, the minor and the superficial so I was looking for someone who would be sensitive to these aspects and happy to engage with this terrain. For the first exhibition it was important that the artworks presented enable a self-reflexive mode of the set-up and highlight the inherent properties of the space surrounding them. To first understand what the space does in its current form on encountering artworks before choosing to push it into more radical and new configurations, if you will. So the first show was as much Mădălina Zaharia’s work as the flat which housed it. I invited her to do a show because she is an old friend and I was very familiar with her practice and particularly intrigued by her interest in the use of furniture items in popular idioms. I admire her visual vocabulary and her penchant for the absurd. She chose to anchor her exhibition in an 1840 essay by Edgar Allan Poe entitled The Philosophy of Furniture in which Poe discusses matters of taste in interior decoration and strongly criticises the bad taste of the American bourgeois who emulates a European aristocratic tradition that the republic never actually possessed. He also puts forward the idea that interior decoration should be judged similarly to a work of art. I liked the contentiousness of this statement and wondered whether its opposite might be true.

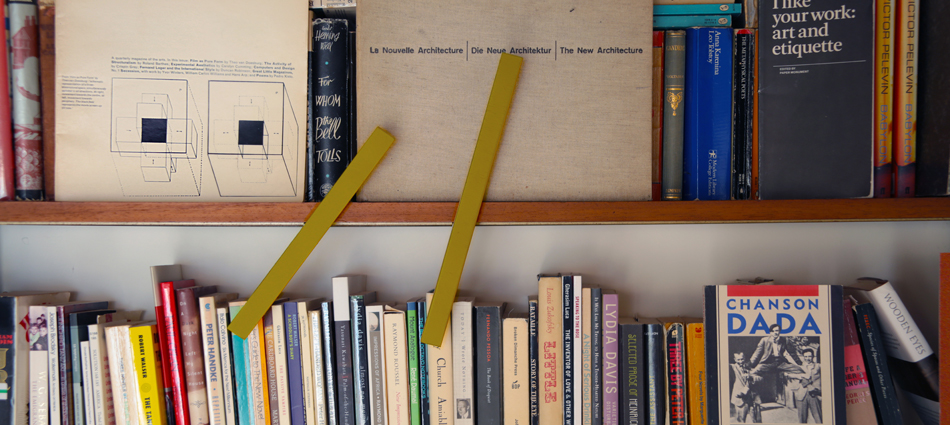

All of the works Mădălina has made for her exhibition at Ingrid possess a self-consciousness as both artworks and decoration and were so skillfully integrated into the overall arrangement of the room that on a first glance seemed to have dissolved into the architecture. A case-in-point was her vinyl wallpaper design which translated E. A. Poe’s tenets on interior decoration and rendered them into a geometric patterning akin to a language – a diagrammatic, impenetrable, decorative morphology literally embedded into the architecture. This work as well as the rest of the installation poses an interesting tension between frippery and formality which speaks of a wider ambivalence in the relationship between modernism and decoration. The repeated dismissal of decoration within Modernism is well-known – from Adolf Loos’ condemnation of ornament as antithetic to the evolution of culture in his famous manifesto Ornament and Crime, to Le Corbusier calling it an abominable little perversion – pattern and ornamentation have remained embedded into the Western cultural psyche as emblematic of vulgarity and unrefinement. But why should interior decoration be seen as embarrassing and discrediting in relation to high art? I believe there is a more complex relationship between modernism and decoration than that of binary opposition and Mădălina Zaharia’s work displays a productive ambiguity in the way it positions itself in relation to this conflict. The overall quality of her installation tends toward ornament with its almost baroque flourishes yet her concentrated compositions aspire to a certain austerity. Their sculptural dimension dissolves into a decorative surface which rather ironically exhibits the ‘flatness’ of the picture plane that Clement Greenberg deemed necessary for abstract painting to transport itself from ‘wallpaper patterns’ to high art. Her work puts itself in a compromised position, which carries within itself conflicts of interest that even risk being self-defeating and I think is stronger for it.

The elements of furniture in her prints and in the animation work appear familiar and at the same time alienated from their usual communicative capacities which in their abstracted presentations become pure form, oblivious to their functionality. The animation functions in a similar way by fusing the reality of an object with its virtual depiction. In this case an industrially produced chair appropriated from a furniture display on the internet. By replacing and re-purposing the original tabletop into a display platform for the showcase of an animated chair, a conscious correspondence is struck between the concreteness of the grey tabletop and the immateriality of the grey flatscreen onto which the chair is performing an endless 360 degrees swivel. Like the self-generated tempo of a skipping CD or the idleness of a screensaver loop, it is forever revolving in its persuasive pursuit at commercialised seduction. But there is an honesty in its persuasion as this chair isn’t trying to be anything other than itself. Sometimes ‘a good chair is a good chair’ as Donald Judd would say.

How could these works be classified, in terms of medium, aesthetics and function?

The works relate to different disciplines – to the discipline of sculpture, to the art of installation, exhibition display and interior design. They behave in a way that references furniture, an abstracted chair or the movement of a cabinet door. They don’t read like functional furniture or interior decoration but have the attributes, the sensibility of furniture and a decorative morphology both in their materiality and the specificity of their placing in the room. Functioning in the key of interior design – considering all the parts and their placement in an environment, determining the flow of a room and how one moves through and views the objects.

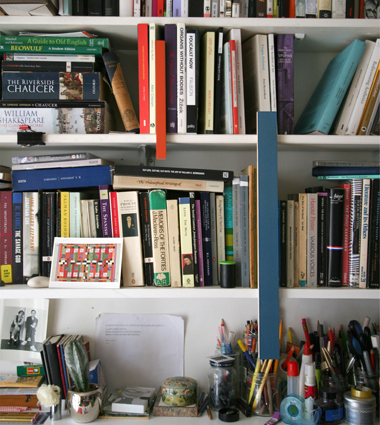

Hence, her sculptural geometries take the guise of domestic decorations. Poised between the scenographic, the sculptural and the painterly, abstracted vertical and diagonal lines are given physical presence in a series of sculptures. Their clean lines and structured forms contrast with the messy conglomeration of colours and typefonts on the book spines they were derived from and which act as their backdrop. Perched around the room, they seem to be hovering in the air, their sculptural quality emphasized and undermined by their lightness and flat surfaces, situating themselves somewhere between props and graphic glyphs, caught in the act of an illegible private conversation. They possess a type of cartoon economy and their bright colours make them seem like a dance of abstract lines and shapes, as if they jumped out of an Oskar Fischinger animation right into a tridimensional setting. They behave like abstracted units of furniture and choreograph the viewing.

What is then the new understanding you are proposing for the relation between art and decoration?

I enjoy Greenberg’s disdainful description of Robert Motherwell’s paintings as possessing an ‘archness like that of the interior decorator who stakes everything on a happy placing’. But is ‘the happy placing of an interior decorator’ really a complaint, or is it not a compliment?

Mădălina Zaharia, A well-furnished room, was at Ingrid Projects London between 4 October – 12 November 2014.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.