May 12, 2015

By Cristina Bogdan

Something Proper

The proposal extended to this year’s participants at the Venice Biennial was to tackle, once more, the Western canon – aesthetically, socially, politically or commercially. Curator Okwui Enwezor directed with confidence the range of replies.

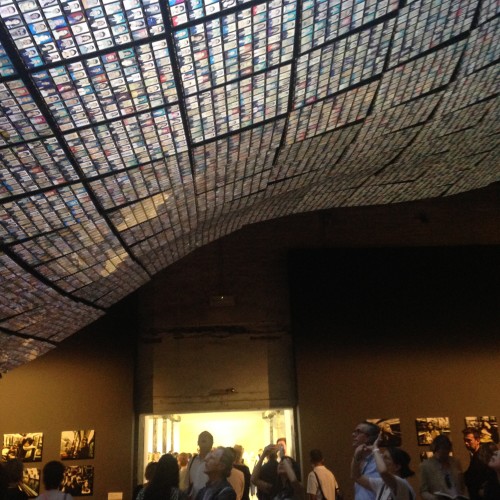

Already in the Arena, the heart of the Giardini, one can sense a physical energy that leads to performance. The e-flux supercommunity – who already invited everyone in – is the perfect hub for the entire project. Colonialists past, present and future, formalists, financers, guilty neutrals, losers and some slaves all round up. The Arena is a continuous revelation and the national pavilions are a continuous déjà-vu. Of course, one’s revelation is another’s déjà-vu. We need to make things clear.

The Arena is a mini-Arsenale with a stage in the middle, where the best pieces of the Biennale can be seen – for example the e-flux discussions or Ivana Müller’s performance where the public reads her theater play and becomes the performance. In the rest of the Giardini, the global North has a predictable and professional grasp on things, sending over professional designers, nature-conscious artists, archivers of the present or even monuments (Joan Jonas). The same old auto-da-fé white cube breeze is blowing throughout.

The global South, Russia for instance, takes the opportunity to show us that even during more complicated periods of time (the 90’s in this case), someone is still resisting. Szilárd Cseke of the Hungarian pavilion sees the entire space as a metaphor for the present: the center is empty and all around are these transparent tubes with little moving spheres. Farther away, next to Piazza San Marco, Simon Denny fully accepts Enwezor’s challenge and proposes an iconography of the world post-Snowden. But how does Romania answer to this challenge?

The old dilemma that every non-Western artist has to face is: how to make authentic art that proves the artist knows the Western codes yet he has already subverted them, that he has assimilated his own background and even re-assimilated it after living a few years abroad, that he criticizes the West as well as his own background, that he pays attention to his own attraction towards beauty, that he is neither exotic, nor conceptual, nor a humble copy-cat, that he knows his own craft although that doesn’t matter, yet he knows that he knows, that he takes advantage of his outsider stance but secretly thinks himself a classic and that at the end of the day he doesn’t even ask this question because it’s so not contemporary. Basically, the challenge is to go from Provincial to Authentic. And one manages to do so only if something is to be found behind their formal exercise. Something other.

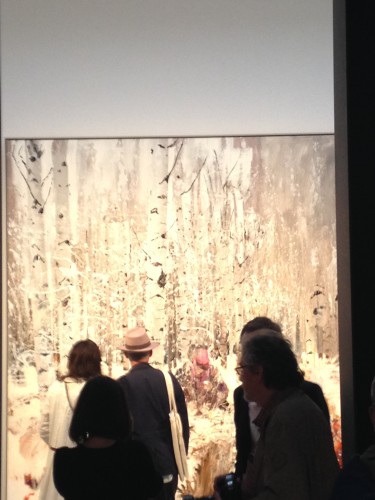

Now, behind the freshly renovated, black and white painted pavilion containing assorted black frames with Adrian Ghenie’s paintings, there is surely something. There is an aesthetic and pictorial project hidden somewhere deep, but which in the design of a commercial art gallery – something absolutely eccentric in the context of a Biennale where everyone in the same situation else pushed the limits as much as they could – is perfectly lost. Closer to the surface, a project that no art person missed – the desire to institutionally legitimize an artist with commercial success. The coat on top is that transparent film which makes the whole exhibition shine for those seeking the Authentic. Overall, a strange object whose function is yet to be announced.

In retrospect, some of Arsenale’s echoes can be heard all the way back at the Romanian pavilion. Enwezor selected a lot of beautiful artworks, beautiful as you’ve not seen for ever in a Western gallery. Masculine, colorful, energetic and exuberant works made without any pressure by Ofili, Holler, Boltanski or the less famous Propeller Group and Katharina Grosse, revitalize the mental space of contemporary art. Ghenie’s paintings can also do that, especially when they’re not trying to. The artist is in perfect harmony with the figure of the creator – the virtuous painter who never succumbed to new techniques – a dear Eastern myth of resistance.

But let’s have a look at some other possibilities. One pavilion that shocked me in the context of the Biennale was Azerbaijan’s, where four artists who were active in the 1960s-80s have been recently – what else – rediscovered. At first sight, it appears to be an exhibition held in a community center funded by lottery money. But the real shock came when I realized that Romania was in a similar position of putting forward a pavilion project that would have been ex-centric, yet not the cowardly way. Romania had the chance to speak about a past that has been left untouched for so long, the chance for young researchers, curators and artists to finally have a dialogue with an unfriendly and incomprehensible history that never offered them anything. Enwezor’s presence, a curator of Nigerian origins, signifies that there was the possibility for precisely these kinds of projects to get the attention they deserve, to be read in a context that wouldn’t denature them – or at least not as much as usual. I’m not saying that Azerbaijan did just that – it rather appears to be a Western fake with a provincial touch and possible settling of scores on some political level. But I wonder why we chose the easy way out – selecting an artist with historical portraits to make a commercial gallery show – when we had the opportunity to make a valid statement for both people living in Romania, as well those who see us from the outside. Why not a well curated show of the famous art school of Cluj. Why a salon type exhibition when the artist’s home gallery, Plan B, is one of the most up to date in Romania.

The answer could lay with the second Romanian project in Venice, Inventing the Truth. Diana Marincu is one of the best curators in Romania; all of her shows managed to present the artists in a professional manner, and that is saying a lot for Romania. The project that was the basis of the ICR Venice show was the best group show of 2014 and if Inventing the Truth were presented in Bucharest, it would have surely been the best show of 2015. But in the context of the Biennale you barely even notice it. It’s so unassuming, correct and lacking of charisma that it doesn’t bother you, either when you’re in the tiny ICR gallery or after you’ve left. The presentation text is in International Art English, the chromatic pallet is black-white-gray and the subject is history, probably the safest road for all young artists who are looking to squeeze in.

But this is because the group’s project doesn’t want to produce art – the artists and the curator are rather looking to make way for future young Romanian artists that exhibit their works in established contexts to be judged for something other than their background. There already are a few notable projects that managed to pull this off and this includes last edition’s Romanian pavilion in Venice. Nevertheless, the lack of any coherence in Romania’s cultural policies turns any Western standard exhibition into precisely this: a bland western standard exhibition. What I can take from all this is that this fear doesn’t come from exhibiting your own art, rather the fear is maintained by the idea that your art looks nothing like the right type of art. This position plays a certain role in the grand concept of contemporary art, but at the same time it has an expiry date; if it takes us another 10 years to reach a certain level, we risk getting bored ourselves.

Myself, I identify with the questions of this group rather than those raised by the national pavilion, although the pessimistic version would be that both of them are just different degrees of the same question. Inventing the Truth was produced by authentic artists that deserve a good reading of their works and that managed to create a context of normality that seemed to be expected in the Romanian art scene. It is surely one of the replies Enwezor was looking for. I can only add that if this is the path that was chosen, there are still some steps to be taken. Otherwise, it’s back to drawing board.

Maybe the answer to this type of dilemma – and it’s possible that I am exaggerating when I consider this central to the project, but I am used to see any type of art as an outsider – lies in another ex-centric country’s pavilion, Angola. As you step in, on the left hand side you can see art that you should NOT make if you belong in a non-Western country, meaning no traditional plastic sculptures, no installations out of local propaganda posters that were salvaged, filmed and projected on the floor, nothing that seems like you might be actually trying. On the right hand side however, we have the perfect object, the very essence of the whole Biennale, a short video about 4 black kids digging a hole for themselves in the sand and pretending they’re in a convertible – they talk the way adults do, going over the same fears, limitations and praise as adults, re-producing their own context. Continuous mirroring of the spectator, visible yet compact layers and a naiveté that makes the whole thing seem as authentic as possible. It’s very difficult to make something so good, yet so simple. Unfortunately, whenever someone nails it, it cancels out all the former wry attempts, no matter how proper they seemed.

All the World’s Futures, the 56th edition of the Venice Biennial, curated by Okwui Enwezor, takes place between 9 May – 22 November 2015.

Romania’s national pavilion is Adrian Ghenie: Darwin’s Room. Curated by Mihai Pop.

At ICR Venice is Inventing the Truth. Artists: Michele Bressan, Carmen Dobre-Hametner, Alex Mirutziu, Lea Rasovszky, Ștefan Sava, Larisa Sitar. Curated by Diana Marincu.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org