In the search for what it means to be contemporarily relevant, the experience that the residency in the Czech Republic offered me was an opportunity to get acquainted with and visually explore the most important exhibition spaces, galleries and museums alike, of Prague and Brno. Among the most relevant museum spaced I saw were the National Gallery in Prague and House of Arts Brno.

My curiosity was especially directed towards the National Gallery and its temporary exhibitions, as I wanted to see what kind of selection of established artists is visible in such a relevant institution. Said selection encompassed Czech as well as international artists, from nationally established names (Magdalena Jetelová) to young artists (Pavla Dundálková) to world-renown superstars like Ai Weiwei and Brian Eno.

My experience in the National Gallery spanned one whole day and was a roller coaster of swirling sensations and thoughts, having been faced with a mix of extremely different, yet individually striking artists. The first project that greeted me was Magdalena Jetelová’s Touch of Time, curated by Milena Kalinovska, which continued on the floor above with a selection of the artist’s works from the ‘80s till today. This mini-retrospective carried me inside the creative universe of an extremely prolific and powerful artist, with an impressive artistic path, in regards to the gamut of techniques experimented with along her career, as well as to the concepts supported by these visual media. The installation at the entrance to the Trade Fair Palace was conceived as site-specific, as a metaphor for a dialogue with the building’s architecture through the vibrations of the plates that mirrored the space, as well as as an invitation to reflect on the social and political instabilities in today’s world. The reality mirrored by Magdalenei Jetelová’s installation is displayed as brittle, fragile, by means of the vibrating fake mirrors, which actually reflect the exhibition space and the viewers. The artist’s position is both critical and poetic, through the way in which she makes use of the materials and the space.

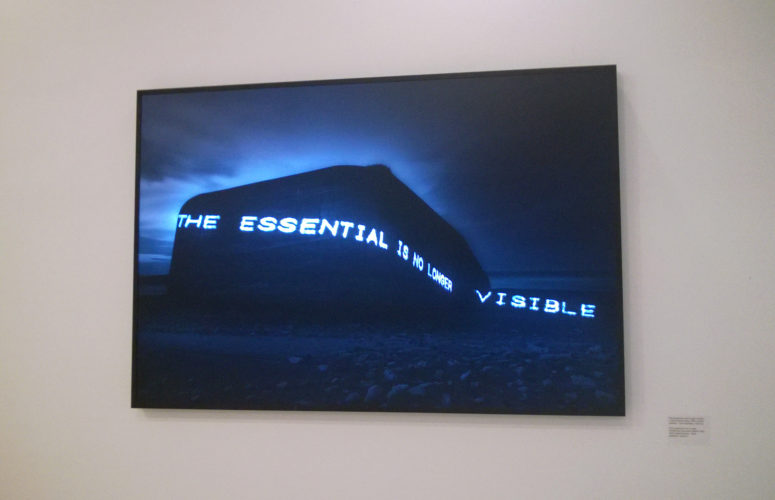

The floor above presents a selection of works which showcase the influences she had along her career: an example would be the Arte Povera “effect”, for the period in which she was studying in Italy; another would be the artists contemporary with her: James Coleman (one of her teachers) or British sculptor Richard Deacon. In her exhibition history, she participated in events in massive institutions, like Tate London, Riverside Studios London, MoMA New York, Documenta 8, and the Sidney Biennial. What struck me in my passing through Touch of Time is the versatility and the – I dare say – grandiose production, both technically and ideationally, of her works. Starting from sculpture, Magdalena Jetelová goes on to create sculptural objects that function as installations in different display formulas. One of the main themes that the artist tackles is connection, the meeting, which becomes a metaphor for the relationship established between the materials she uses and the subjects of the works. Magdalena Jetelová is preoccupied by esthetic organic experiments, in somewhat traditional plastic techniques, but also minimalist-conceptual ones, transposed in new media. Hard materials become almost fluid and weightless in the artist’s vision, and the capacity to transgress the boundaries of the predictable and to retrace some coordinates of the relationship between matter and its image (evident in the photo series presented as light boxes) outlines what I’d call an innovative, even original vision.

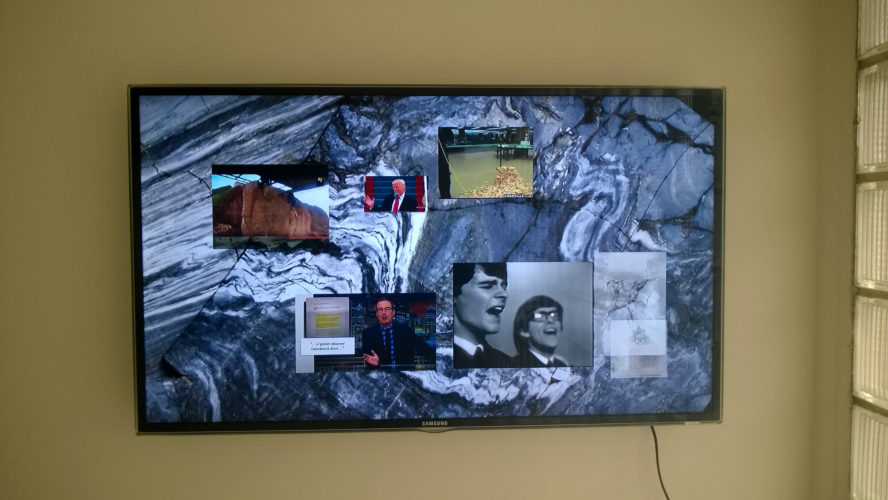

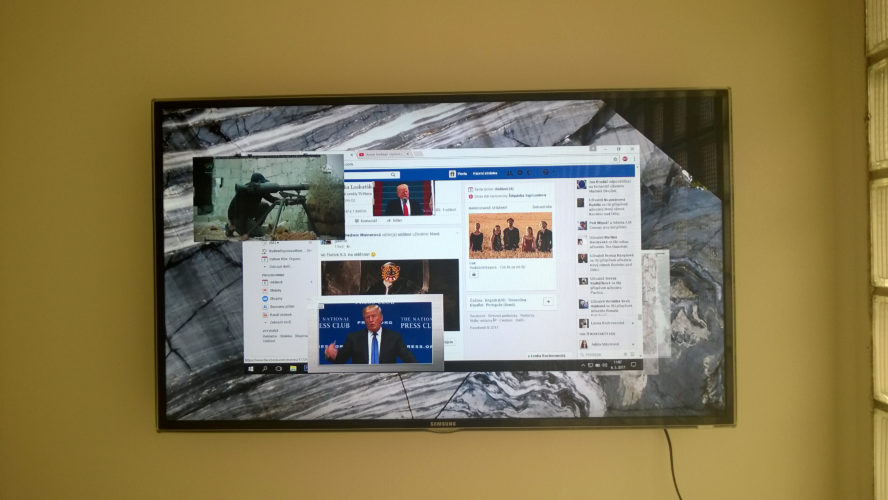

Pavla Dundálková’s When I Close My Window I Don’t Hear The Street Noise was one of the most intriguing exhibitions I saw during my stay in Prague. My meet-up and chat with her in the National Gallery’s café amplified the image I had made from the beginning – her main quality being an incredible analytic capacity, inserted in a remarkable sensitivity. Pavla Dundálková uses, as a pretext, the motif of the window as a transitory element between inside and outside, but analyzed and portrayed in present formulas. The contemporary window, with which the artist operates, oscillates from the drawn image of a window, to the photographic image, collated in drawn frames, and even to representations with volume, through elements of bas-relief applied to laptop screens (digital windows), and to social media windows and pop-ups on plasma TVs. She conceives a space-as-a-refuge with a metaphysical atmosphere in which she questions concepts that are now almost cliché – like the paradoxical lack of communication and the more or less conscious disavowal of inter-human connections in a hyper-technologized century. She puts in relationship and materializes contrasting situations between traditional (sculpture) and new media of expression. She sees no barriers in transposing a concept in a certain singular technique, seeing her praxis instead as an act of fluidly combining multiple techniques that potentiate her ideas. An artist with introspective vision, highly sensitive in perceiving and interpreting reality, which narrates her own universe with an atypical modesty – marked by shyness at times – yet anchored in the present she inhabits.

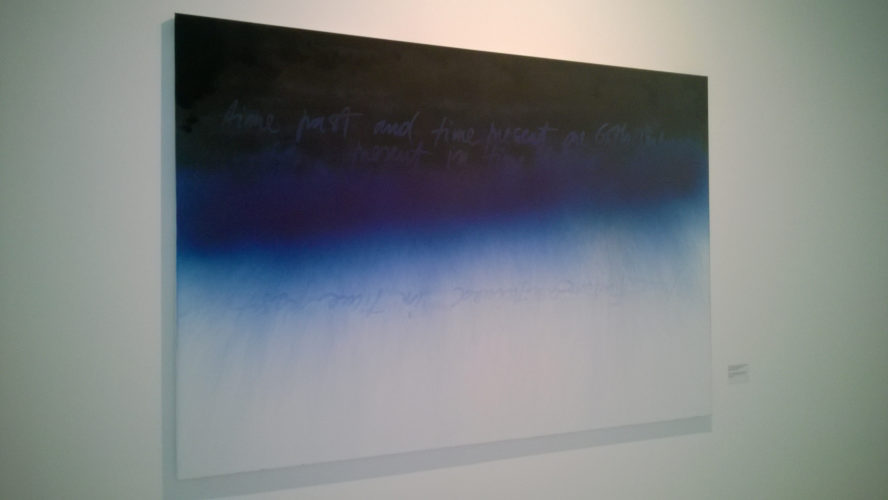

Brian Eno’s installation The Ship, from the National Gallery’s Moving Image Department sent chills down my spine; I spend a full half hour in the room where it was exhibited. The artist managed to create a solemn, dramatic, almost funerary atmosphere, by means of sound, light/darkness interplay, and a few carefully placed objects: speakers arranged in the shape of a cross, candles, and carefully constructed aisles. The feeling of vacuity in that precisely fabricated darkness, like a digital temple in which musical fragments reverberated, the voices and sounds that felt plucked from a warzone, paralyzed me in a state of taking in the feeling of anxiety that the space conjured in me. I emphasize the sensorial character of The Ship project, as the impact that the artist achieved with this installation is definitely a personal one on a sensitive level. An installation of mainly sound art, on 25 channels, described by the artist as a music novel and compared to a “theater of the mind”, it incorporates multiple types of sound, including human voices, creating an apocalyptic atmosphere. The Ship is constructed as an experience that can be seen as time travel, a temporal breach, a terminus point of contemplating the past and the present, or even as a parallel reality. The space that Brian Eno manages to create leaves you breathless, almost forcing you into a moment of introspection, inserting at the end of the installation Lou Reed’s lyrics “I’m free to find a new illusion”, and even his own voice in a sound experiment he dubs “spatial song”.

Ai Weiwei with his new project Law of the Journey is, as always, monumental, spectacular, making me constantly wonder how far he will experiment, what barriers he will transgress, what will he surprise with next. The main theme of his installations in the show is one of the greatest and most recent problems contemporary society faces today, namely the refugee crisis. Ai Weiwei assembles installations out of tweets, lifejackets, clothes and objects belonging to refugees, and photos taken at the scene where he travelled himself in order to document the state of the people in this predicament. The artist aims to challenge the viewer and draw attention to the harsh realities by reemploying objects that were part of the events which he analyzes and criticizes. The work that the viewer certainly won’t forget is certainly the huge ten meter lifeboat with survivors, augmenting through this visual formula the importance of the examined topic and our infinitesimal position in the face of the catastrophe. In a society and an age when selfie-fueled narcissism takes up a good chunk of the contemporary individual’s life, the artist directs one’s attention from the ego to the outside world, to the others, the ones less visible on our virtual reality’s daily newsfeed. Ai Weiwei accustomed us to a certain type of adrenaline, with a spectacular race that can become duplicitous, opportunist even, in the hunt for new hot topics beguile us, more or less gratuitously. The artist is exhibiting these works in the Czech Republic in order to stir controversy, as it is among the European countries which refused to take in refugees. The way in which he tries to get our attention can be seen as facile, making use of his status as public person and superstar on the international art scene in order to manipulate public opinion and to stir controversy in a cheap, even immoral formula. Conceiving such a relational installation, with such a sensitive topic in mind as the dire situation in which these refugees find themselves in can be seen as a means for the artist to draw attention to himself, and not to the social issue he examines, which exhibits, in the end, a boomerang effect.

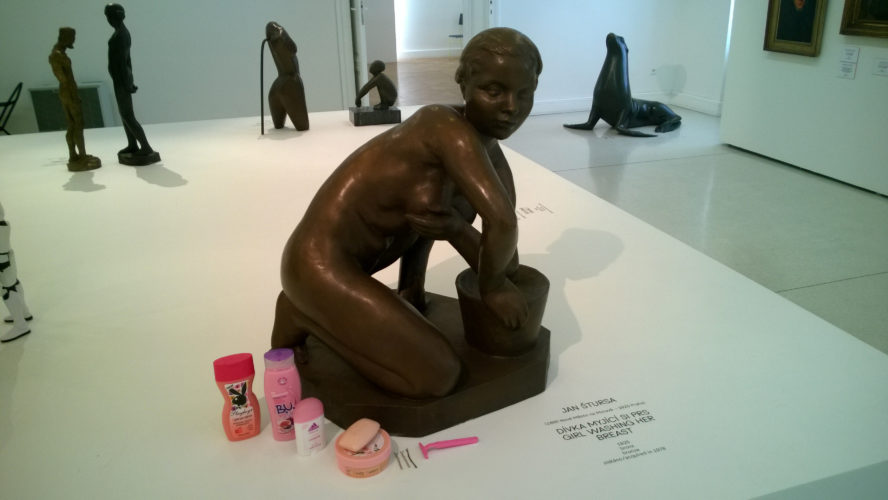

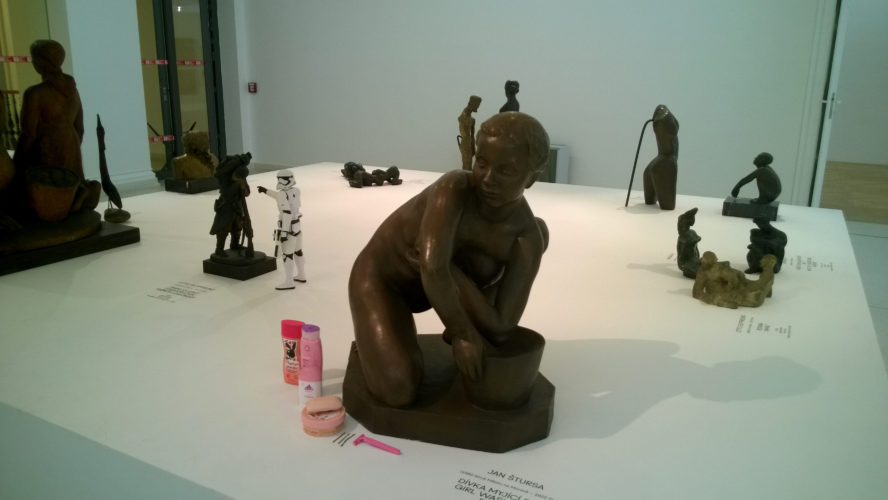

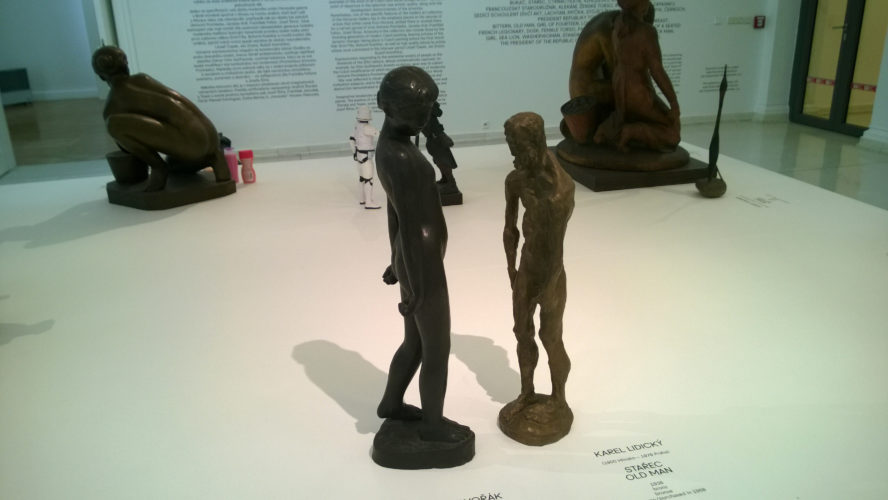

House of Arts Brno was a pleasant surprise with its impressive collection of heritage works, especially of modern art. I remembered and remarked especially an intervention on some sculptures from the museum’s collection of artist Maxim Velčovský. He declared in his statement: „I do not see my installation as a traditional „best of” show, but rather as an intervention in this warehouse full of various opinions, ideas and formal approaches.” Maxim Velčovský puts together an ensemble of works placed in the center of one of the museum’s rooms, in which he ironizes, recontextualizes, and questions the status of the exhibited sculptures, in order to potentiate the perceptual relativity of so-called established values. Time consecrates and, at the same time, spawns perceptual dilemmas, and the artist is lucidly aware of this fact. He therefore conceives of a caustic display formula for the museum pieces, in the shape of a dialogue which juxtaposes daily life items (cosmetics, a razor blade), toys portraying characters from famous movies, like Star Wars, balls, etc., with the aim of provoking a different kind of response to axiom-type objects. One can say that he operates like Marcel Duchamp. As a consequence, the cliché perception of the museum goer is forcefully directed towards a proposal for an ironic vision of the concept of “established”, of “eternal”, and, last but not least towards the relativity of the exhibition space. Maxim Velčovský’s intervention becomes an exercise in becoming aware of creative possibilities, a conscious play in which he underlines the relevance of the contemporary artist in a museum context – in interpreting, recontextualizing, and questioning, or putting into a different perspective generally-accepted truths.

The intensity with which I lived what was delivered to me in the two weeks spent in the Czech Republic “charged” me with energy and new thoughts to last me a while, accelerating some shifts in perspective which had already been kindling in me for some time, but which only found their way to light through these key events. The Czech Republic is a very culturally active country, open towards the West’s influence and opportunities, authentic and inciting as a European art scene. I’d come back any time for a new experience, and I wholeheartedly recommend exploring it. For me it was an opportunity for personal development, for gaining knowledge, and, last but not least, to reevaluate certain realities I confront with. It wasn’t necessarily an answer to the questions I already harbored. I think I simply answered myself with new questions. Which makes me want to walk on, more curious than before.

Ada Muntean’s residency was possible with the support of AFCN, Artalk.cz, The Czech Center in Bucharest and ICR Prague.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Ada Muntean

Ada is a Graduate of University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca and has a PhD in Visual Arts (2019), conceiving a research thesis entitled "The Human Body as Image and Instrument in Contemporary Art....

Comments are closed here.