The golden bathroom was legendary, a vulgar luxury in the midst of a socialist state. “In the surveillance state of Romania, the Ceaușescus demonstratively presented themselves to the public in simple working clothes, but this façade concealed the opulent kitsch, that the dictator couple enjoyed in their private home,” reads Anton Roland Laub’s prologue in his photo book Last Christmas (of Ceaușescu). And there it is in the picture, the bathroom: gold mosaics on the bathtub, shower handle, towel rack, all made of gold, plus floral tiles on the floor and a French-style stool. Tasteless, banal and wasteful, the stuff that bad telenovelas are made of.

Thirty years after the dramatic events of those Christmas days in 1989, Berlin-based photographer Anton Roland Laub visited the places of that time and photographed them: the Ceaușescus’ private villa in Bucharest, the monstrous Casa Poporului (House of the People) for which entire neighbourhoods had to make way and whose inauguration the dictator did not live to see, and the military base in Târgoviște, the old centre of Wallachia, where, on December 25th, 1989, the dictator couple was given a summary show trial: “The trial lasted 55 minutes, the verdict 1 minute and 44 seconds, and the execution less than 10 minutes,” the artist elaborates in his photo book.

The images of the execution on television, the coincidence of Christmas and brutality, shocked the world 31 years ago. Like everyone else, Laub waited in front of the television as a teenager until the images were finally broadcast. Again and again the transmission was postponed, as the videotapes still had to be edited. Incidentally, it was a small irony that the director who edited the film was the same one who had previously shot the great epics glorifying Romanian history for the state film company.

During the interview in Berlin, Anton Roland Laub tells us that he remembers his mixed feelings well: “When I saw the execution on TV for the first time, I was relieved, of course. But the images also stirred me up,” he says. “It also hurt: two frail old people being executed just like that.” Curator Frizzi Krella also recalls the Romanian-German Nobel Prize winner Herta Müller who, having been persecuted by the regime, had every reason to wish the dictator dead, and told Deutschlandfunk radio that she wept bitterly when she saw the pictures of the shooting. Immediately after the event, there were heated debates about whether it had been right to show these pictures, Laub recalls.

The events of 1989 remain unresolved, even thirty years on; a ‘stolen revolution’ still to be dealt with judicially. Who was responsible for the more than one thousand people who died in the street fights, many of them perishing only after the execution of the dictator couple? “The dead of 1989 form the collective trauma of post-communist Romania,” notes Lotte Laub in her essay for the photo book. In December 2019, an EU resolution was passed calling on the Romanian state to come to terms with the past. Anton Roland Laub has experienced for himself that the topic is not necessarily met with interest in Romania, which is precisely why it is so important to the artist to show his work in Romania. It is currently set up in the Romanian Cultural Institute in Berlin – and due to the Corona lockdown can only be viewed by appointment.

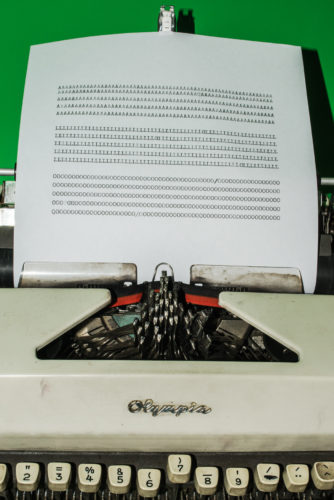

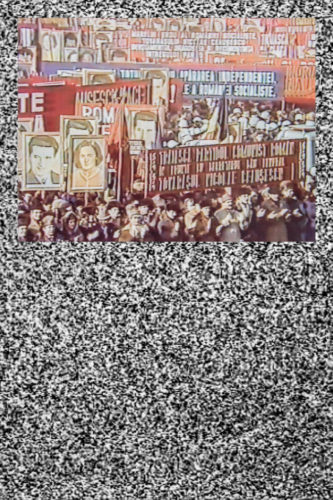

How do we deal with the images and memories of that time today, thirty years later? That is what this work is about. Laub works with historical film footage, Ceaușescu at his last speech, the protesting crowd and the dictator couple before the military tribunal, and he underlays the images with the grainy television snow that could be seen for hours in the eighties – there were only two hours of television a day back then, mainly to stage the dictator couple. And he contrasts this with the images from today’s remains: the obscene pomp of the Ceaușescu villa, Elena Ceaușescu’s furs in the closet, the open safe, the private cinema or the magnificent Louis XVI furniture in the salon and study. And the barren rooms of that military base in Târgoviște: the two metal army beds pushed next to each other, the tin bowls on the table and those two chairs – pushed into the corner and lodged behind tables – on which the couple had to listen to the verdict. The third narrative thread is his father’s Olympia typewriter, on which the latter had to deliver typed text samples for inspection every year. Laub placed it in front of a green screen – and typed “Alo” on it, the hello that Ceaușescu shouted fifteen times into the microphone on December 21, 1989 during his last speech from the balcony of the Central Committee building – the crowd no longer reacted, the dictator fled by helicopter one day later.

It comes across as abstract, like a re-enactment, with that conceptual coolness we know from the crime-scene recreations by the German artist Thomas Demand, the latter nevertheless working differently by recreating crime scenes, such as the State Security (Stasi) headquarters in Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, Saddam Hussein’s underground hide-out or the Oval Office in Washington, in paper and cardboard before photographing them. Anton Roland Laub takes photographs on location but intentionally works with oblique camera angles, cut-outs and plummeting lines; all certainties start to waver. His photographs are conceptual, working with pop references, talmi glamour and image distortions; and banal and charged at one and the same time, like an etude on what can or cannot be read from images, what they reveal, where they deceive. It is also the pop-cultural aspect that interests Laub: the uncanny historical overlap that Târgoviște, the last place where the Ceaușescus stayed, also happens to be where the mythical Vlad Țepes, alias Dracula, had a ‘Forest of the Impaled’ built from the heads of Turks and other enemies on stakes – the very Vlad who Ceaușescu attempted to rehabilitate with a monumental film that was released in 1979. Vampirism, cruelty, death, national myths and traumas – history repeats itself, creates loops, becomes knotted.

This is especially true for the convergence of Christmas and revolution. Laub has already dealt with the topic of religion in his work Mobile Churches in which he follows the traces of churches that had to give way during the ‘systematisation’ of Bucharest; they were lifted up and moved on tracks to the backyards of apartment blocks. Laub photographed the seven churches of Bucharest that were hidden behind socialist functional buildings, like alienated objects or postmodern quotes. Why this elaborate procedure, this rescue of religious spaces by an atheist state? Anton Roland Laub finds it just as much an open question as the execution of the Ceaușescus on Christmas Day of all days: “That was absurd: for breakfast, in the morning, there was the first Christmas mass – until then, church services had been banned on Romanian television. And for dinner there were the corpses, the broadcast of the shooting of the dictator couple.”

Reprint of the German text Alle Gewissheiten geraten ins Wanken. Courtesy of the Märkische Oderzeitung newspaper.

POSTED BY

Christina Tilmann

Christina Tilmann works as head of cultural editorial department of Märkische Oderzeitung. She has been writing on visual arts and film since 1999 and published several books....

www.moz.de/

Comments are closed here.