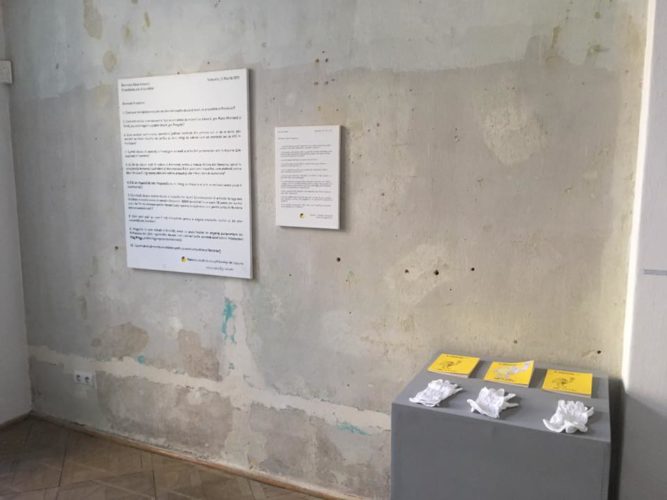

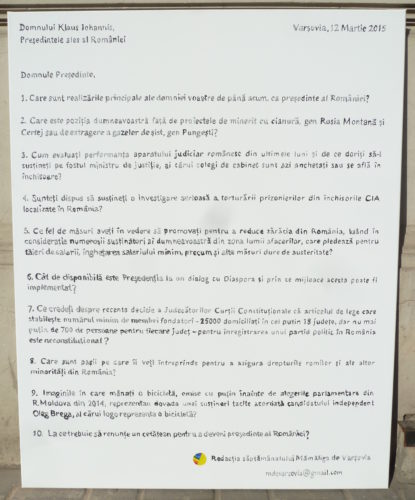

I met Teo Ajder in June, in Warsaw, at an opening at the Palace of Science and Culture, when he also offered me the two then-existing issues of the magazine Mămăligă de Varșovia/Mamałyga warszawska, at which he is a writer, editor, and translator. Of the fact that there is a collective of Romanian expatriates active on the Warsaw culture scene I’d found out a few days before, at an exhibition at the Lokal_30 gallery titled Do or Die/Czyń lub giń. Reopening the old debate about the need for artistic social involvement and connecting it to immediate and local concerns through panel within the Culture Congress – the preparations for which being where the initiative for the exhibition was born – as well as in a 2007 essay by Artur Żmijewski, where he attacks the concept of autonomous art, the exhibition brought together multiple explicitly political art initiatives, though autonomous art is still perceived as dominant in the cultural sphere. Both conceptually and method-wise, the projects were highly diverse, ranging from social projects in the true sense of the word, like the Alfa Omegi project, putting up for sale (within the exhibition) backpacks and footwear handmade by women from a slum in Nairobi, Kenya, to a textual and visual telling of the war in Ukraine by Oksana Briukhovetska, from the subjective p.o.v. of a man met on a train. In this setting there was also a large canvas on which, to my surprise, I saw text in Romanian, and which contained ten questions for Romania’s president Klaus Iohannis, signed by “Redacția săptămânalului Mămăligă de Varșovia” [the editorial board of the Mămălligă de Varșovia weekly]. Apparently they wanted to deliver it personally to the president during his official visit to Poland in 2015, at a meeting with the Romanian Diaspora at the Warsaw embassy. In the end, the questions were handed on a piece of paper to his spokesperson, to be forwarded to the president. They are still awaiting reply, and the painting itself was never sent. The whole story is told in the first issue of the magazine, along with a humorous exchange of messages between the editors regarding whether they should post on social media a photo of them with the canvas in the background of which (the photo) there was a skull.

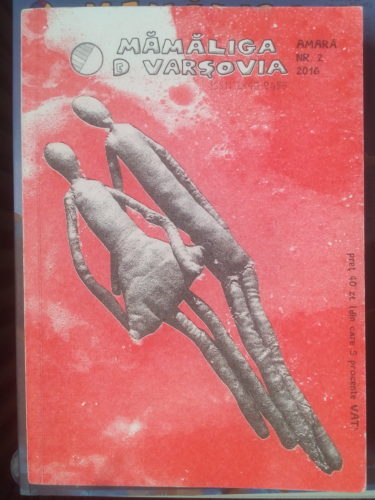

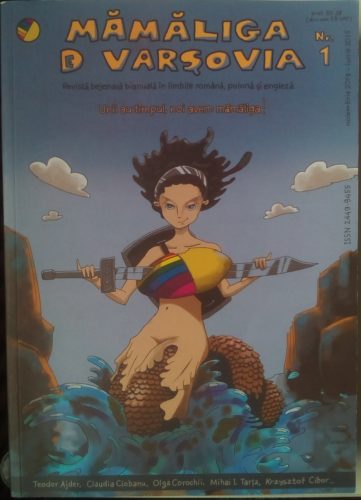

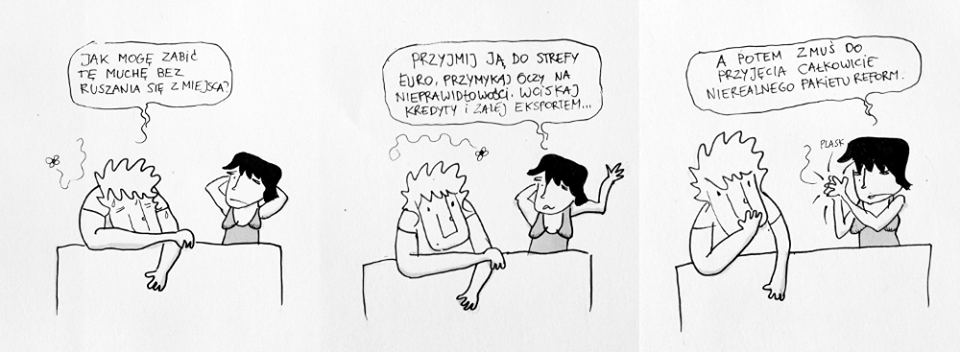

By this detour I meant to underline the fact that Mămăligă de Varșovia (“Warsaw Bitter Maize Porridge” – on their second issue) does not exist solely on paper, but is the product a socially engaged and culturally active collective, to whose actions the magazine is at times complementary. Reading through the publication we find out for instance about a children’s book club in Romanian, a flower-planting initiative on the 1st of May, as well as about a public talk on austerity and its religious appeal (according to the speakers) to certain individuals and governments, held by Mihai Tarța and Vitalie Sprînceană, moderated by Teo Ajder, with a number of interventions from the audience (all of these in Warsaw). The magazine’s launch events are also documented, one taking place at the Moldovan Embassy in France. Aside from the events organized by the editorial staff, we have numerous impressions of cultural events in Warsaw, as well as exhibition and book reviews. The editorial board of the magazine, which is trilingual, with an emphasis on Romanian, is made up of Teodor Ajder, Claudia Ciobanu, Olga Corochi și Mihai I. Tarța, each with his/her own distinct textual voice. Adding to its personality, the magazine has its own font, comic panels by Krzysztof Cibor, and even a mascot – a half-rainbow polenta, with a brief, kind of surrealist backstory in the first issue.

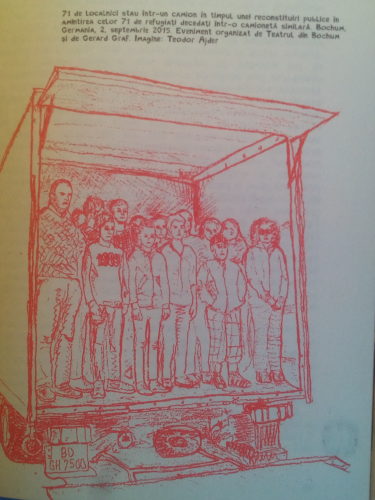

They also run a blog, where some of the texts that find their way into the print version are published for the first time. Both issues are, as the very open nature of the magazine would dictate, eclectic content-wise, also containing, besides what I already mentioned, opinion pieces on international politics, recipes, and short stories. Thematically, the second issue is more thematically focused, around the issue of migration. This identity of the magazine as a platform for expat voices everywhere is of course implicit in the first issue, but it’s in the second one that we see a more conscious militant position, on topics ranging from the refugees crossing the Mediterranean or who become the victims of human traffickers to Chechen asylum seekers in Poland, to day-to-day worries of an immigrant to a country whose language they didn’t master, on how adapting to such an environment and having a family there raises unforeseen quotidian quandaries decisions, like what to name your children or what language to speak to them in at home.

I don’t want to get too specific, since I could fill this article and more just with retold anecdotes, taken from analyses, interviews, confessions, etc., each with a unique voice behind it. Sure, some themes come up more frequently than others, but I feel I’d be denying each case its uniqueness if I were to begin an analysis from abstract categories and work my way down, every micro-narrative flowing into something grander, vaguer, fragmented, that we can easily identify with. This isn’t to deny the relevant systemic issues that transpire in some of the texts.

The issue of national identity is also present. The magazine is, as is stated in the opening text “of the Romanians in Poland”, but, some editors being from the Republic of Moldova, this is a more nuanced statement. They write in Romanian, but the Romanian and Moldovan Diasporas are each sketched with their particularities. We have for instance a critique signed by Mihai Tarța of both a Romanian unionist discourse and of a certain pro-union arbiter/big brother discourse, uncritically adopting a Romanian-centrist perspective, coming from the Polish side.

I certainly appreciate the cohesion, the feeling of belonging propagated through the magazine and beyond it to the Romanian-speaking community in Warsaw and the Diaspora in general. It’s also an example of how an immigrant can view their role in the new society they find themselves in as well as their link with “back home”, and the kind of social involvement and responsibility described in the publication can only be, I feel, enhanced by belonging to a community. Those we read about really want to contribute actively to Polish society, from organizing events with a local target-audience to voting in local elections, being at the same time attentive to things going on back home – I’d cite here a text by Vitalie Vovc, as well as Teo Ajder’s response to it, about the parliamentary elections in Moldova at the end of 2014. They constantly straddle the two worlds, the language and culture they bring from home, both written about extensively in the magazine, and the new environment, to whose taxes and laws they are subjected, and into which they want to become immersed. What’s truly enriching in my view is these cultural hybrids spawned by such interactions, among which the magazine itself, and whose development I can only acclaim.

This isn’t to say the worldview one might get reading the publication is overwhelmingly optimistic. The need for involvement, for fighting for right transpires, in most of the texts, even if it’s not mentioned explicitly or if the tone doesn’t seem to suggest it, but is only the logical conclusion of the indignation felt after reading various stories of flagrant injustice (especially in issue #2). The scope of the magazine doesn’t stop at the national (Romanian or Moldovan) level, and I feel the Romanian/English/Polish-language voices, setting their national, and of course relevant particularities aside, identify on a fundamental level with that of an “immigrant in general”, who is entitled to certain rights, who is perhaps unsettled by a certain virulent discourse or, to return to where we started, by the legal regresses on the part of the Polish state.

POSTED BY

Rareș Grozea

Rareș Grozea (born 1995) got his B.A. in Art History from the University of Bucharest and is currently studying for a Master's in Berlin....

Comments are closed here.