IDEA Publishing House recently released a publication that has been long overdue, covering an almost invisible area of the Romanian contemporary art scene: performance art. Metaphor. Protest. Concept. Performance art in Romania and Moldova aims to map the artists who approach this medium in all its plurality of forms. Performance does not have a vast history in Romania: unlike other countries from the former Soviet bloc, few artists have worked with performance art before the revolution. After ’89, video art, photography and art installation caught the attention of experimenting artists, rather than performance art. We are also talking about a medium that is quite difficult to classify and document, especially in the 1980s, which left behind only a small archive. And so, this volume aims to fill the gap that has existed thus far in artistic publications. Meanwhile, performance art has become a more approachable language, especially for young artists, culminating with Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmuş’s project at the Venice Biennale in 2013.

It becomes evident today that performance is found in increasingly diverse projects that touch on social issues, queer intersectionality, feminism, political activism, but also a metaphysical questioning area of the ephemeral and the immateriality of a performative artistic act and of artistic production itself. The interdisciplinary character of performance makes it a veritable umbrella for artistic manifestations that occupy both the art gallery and the stage. Metaphor. Protest. Concept. Performing art in Romania and Moldova brings together artists from recent history that have worked predominantly in the performantive area, but the unique and very useful aspect for contemporary art is that it entirely consists of interviews. Therefore, the book is not meant to be an academic publication, nor a historical one; the interview becomes the quasi-anthropological instrument for understanding the practice of artists directly from them. Iulia Popovici and Raluca Voinea gathered a series of unmediated accounts about the artistic methodology and process, which are often more important than the final product, from the actors of a relatively small scene with vastly different backgrounds. More than the mere account of certain events, this book also has a confessional dimension: artists reveal the personal dramas that have affected their careers in one way or another, so as a reader, it’s difficult not to empathize with their hardships in their attempt to elevate this artistic movement that is so underestimated locally. The book is bilingual Romanian-English.

The book’s cover show Dan Perjovschi and Farid Fairuz during the project Hysteria / History (2007), two artists whose works come from completely different areas: Perjovschi is famous today for his graphic drawings on sociopolitical themes, with his very recognizable style, but his repertoire also includes important works of performance art, being one of the few artists to perform before 89; Farid, by his real name Mihai Mihalcea, was one of the pioneers of contemporary Romanian dance and fought for its institutionalization and visibility on the national and international scene. He was a key member of the National Center for Dance, the converging point for all experiments in the performative area, accepting leadership even during the critical period in which the CNDB lost its headquarters at The Bucharest National Theater. The administrative and institutional changes, as well as the public’s reactions gave life to the character of Farid Fairuz, which was shaped in a kind of Mihai Mihalcea’s ID. Fairuz had the voice and courage to speak frankly. His subversive performances sparked all sorts of reactions, pushing Farid into a theater / dance / activism hybrid that is akin to magical realism. He has always been interested in working in the public space, so he collaborated with Perjovschi on Hysteria / History, a key performance for the recent history of local art, in which Alexandra Pirici and Claudiu Cobilanschi were also a part of.

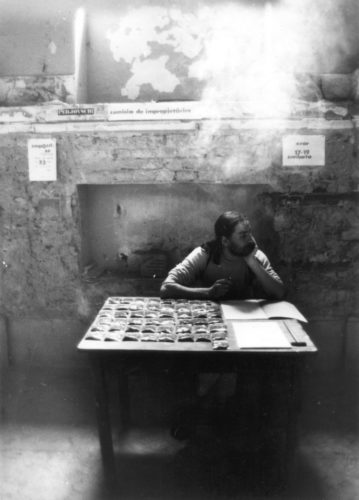

Perjovschi recalls the preparations for this event, as well as his actions during the communist period. He mentions the Zone Festival, the Peripheral Biennial and the Festival held near lake Saint Ana, major events from the past, away from the capital, dedicated to performance art, and the atmosphere back then, the low financial possibilities, but also the sense of belonging and community he no longer senses today. Performance and the ephemeral have always been a part of his art, thus developing his own language that allowed him the artistic coherence which made him famous. He also draws attention to the lack of research and documentary material on performance art in Romania.

These festivals have inspired many to start performing. Arnold Estefan went to school in Sfântu Gheorghe and came into contact with this kind of art through the ten editions of the AnnART festival, a major artistic event where actions of all kinds took place: endurance pieces, works with political or transgressive messages, similar to Viennese actionism, all during the 1990s. Later, Estefan met Anca Benera, and they became partners in life and art, after a long period in which they communicated through art, objects and images. Performance art united them. They used it as an analytical tool and considered it the best medium to express an idea. That is why, beyond the socio-cultural subjects dealt with in the duo’s art, there is also an element of meta-narrative that focuses on the work process itself.

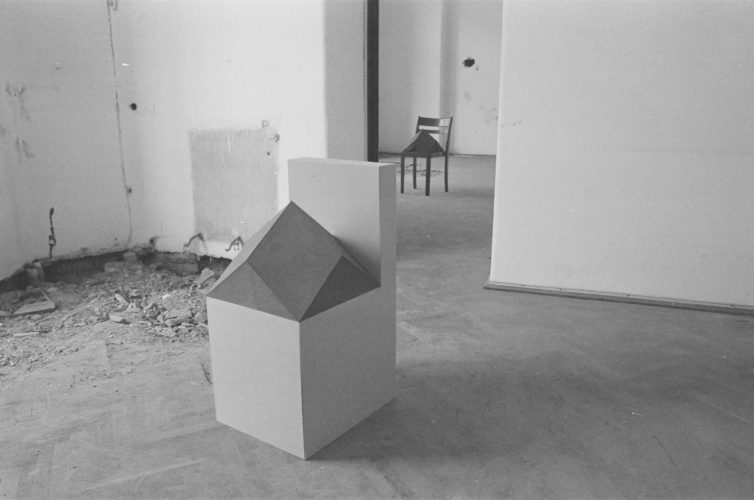

Of course, we can not talk about meta-narratives or questioning artistic mechanisms without bringing up Alexandra Pirici. She has a background in choreography, but she works with various other mediums. Naturally, CNDB provided her with a starting point to go beyond the stage: here she tested new models for actions that were somewhere in between the stage and the gallery space. CNDB’s exclusion from the National Theater sparked a series of protest performance in the public space, which later turned into enactment actions – describing a physical object using the body. In her interview, Pirici goes into detail about what followed after The Venice Biennale and how she pursued her Immaterial Collections series alongside other performers.

Paul Dunca frequently collaborates with Pirici on her projects, but he is better known outside the gallery as a queer activist. Dunca also comes from a background of choreography, mostly seen himself at CNDB along with the affiliate group. His art is very focused on the body: the way it looks, moves, feels or how it identifies in shows like The Institute of Change, actions in the public space, working with disadvantaged communities or during the Queer Night party series, where Paul became Paula Dunker, his gender-bender alter ego. Performance is part of his daily life in which he attempts to to represent the fluidity of gender through his sheer presence within the public space. Activating within the same queer paradigm, couple Simona Dumitriu and Ramona Dima, alongside Ileana Faur, Claudiu Cobilanschi and Marian Dumitru, kept the Platforma space alive. It used to be one of the MNAC annexes which encouraged performance art and activated for many years with almost no budget, but around which a tight community of young artists gathered. From the interview we learn more about the Local Goddesses, a group of feminist artists which was established post-Platforma. In parallel to their curatorial work, the duo also known as Claude & Dersch discuss their autobiographical video performances centered around identity, based on their personal experiences of marginalization both in society as well as in the local art bubble.

The local performance scene has seen several pairs of artists: Alina Popa and Florin Flueraş are both interested in the abstract structures of experience and the way in which performance is present in the most ordinary activities. Their practice is speculative and relies heavily on theory, texts, readings, interventions. Together they devised projects such as Unsorcery, Black Hyper Box or Unexperiences. Popa is also working with Irina Gheorghe as The Bureau of Melodramatic Research, and Flueraş and Ion Dumitrescu have launched the Presidential Candidate, an initiative for interventions within the paradigm of shows and spectacles with the participation of several choreographers.

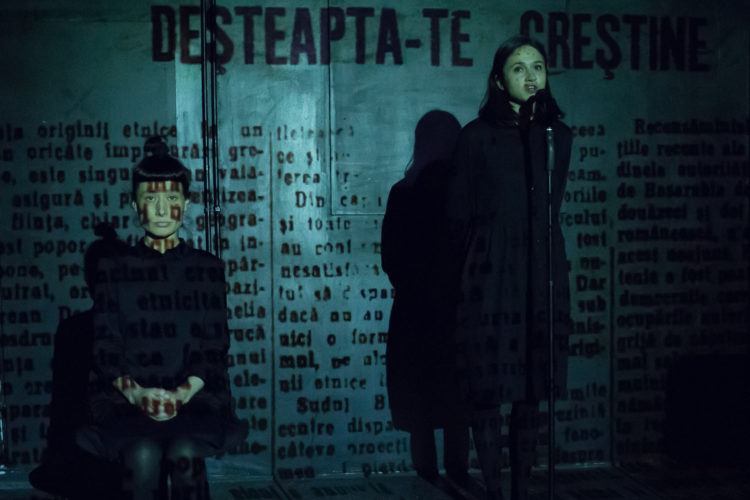

Ioana Păun does not perform, but she uses the stage, the gallery and the public space as a speaking tube to bring various local and global socio-political situations to the attention of the public, with the help of a team of performers, investigative journalists and contemporary intellectuals. Like Pirici, Păun works in a gray area of art and does not believe in the impermeability of artistic groups. She speaks about how she drifted away from the rigidity of theater, and how she became drawn to performance art after her master’s program at Goldsmith University in London. Her accounts, like others featured in the book, highlight the lack of didactic support and interest for the performing arts in Romanian universities. Upon returning to Romania, Ioana could no longer stand the mechanics of classical theater and the mentality of her colleagues when it came to performance art. In addition to documentary theater and the activist themes she approaches, Ioana often works as a curator, always keen to collaborate and promote new artists.

However, the most engaged artist, when it comes to political and activist art, would be Veda Popovici. Through performance art, she talks about about feminist and decolonial practices. She is part of the group that founded the Political Art Gazette, and later on the Macaz space, an autonomous cooperative that acts as a bar, open space for social or activist discussions and a theater. She also teaches at the National University of Arts in Bucharest. Veda recalls she first come into contact with performance art when she was a student in Timișoara. After studying in Paris and Bucharest, she becomes obsessed with theory studies; through performance, her art reveals how we, as a people, position ourselves at a political, social and cultural level according to Western standards.

Metaphor. Protest. Concept. Performance art in Romania and Moldova is a detailed account of the course of these artists, especially in their debut years, focused on the personal experiences and the various contexts that helped them establish an artistic direction. It is interesting to see how all these accounts have precariousness and lack of information as common points. Similar to Veda, others have also abandoned their basic training in favor of performance because of their need for freedom of expression. Matei Bejenaru, a visual artist and professor in Iasi, founder of the Periferic Contemporary Art Biennial, has been working with performance since the 90’s, although he studied painting. The poverty of the community in which he lived in the 1990s prompted him to start performing for the people within that community. Being one of the only artists in Iași who worked with this medium at that time, he caught the attention of the French Institute and was granted the financial support needed to launch the first edition of the Periferic festival. Szilárd Miklós describes the artistic scene in Cluj and talks a lot about the Saint Ana Festival, the ETNA archive, as well as the social discrimination against minorities that was common at that time. Like Păun, Nicoleta Esinescu studied dramaturgy and script writing in Chișinău and uses the theater stage to talk about the injustices of western society. Her accounts, as well as Paul Brăila’s interview are essential for a better understanding of Moldova’s artistic context. Brăila remembers the Soros center in Chișinău in the early 90’s, which paved the way for him to approach performance art and later got him in touch with the art scene in Romania.

This publication from IDEA is essential not only for revealing the methodologies for an extremely wide array of practices but also for the historical recount of various performative manifestations, and more, observed from completely different contexts. We note, however, the common denominator for all those interviewed: hybridity, artistic projects that can not be labeled under one genre. It is obvious that we are talking about a small but close community of artists eager to overcome their limitations and pave the way for others. This community spirit is what gave birth to the performance festivals in Timișoara, Iași and Sfântu Gheorghe, as well as Occupy CNDB; as most of the artists in the book know each other and often collaborate, we learn about all these important happenings from different sources that come to complete the fragmented image of the performative scene.

The lack of books on the history of contemporary Romanian art is more than obvious, especially in the independent sector. Besides established Romanian artists, rarely do local releases document artistic movements or careers as they evolve. This case-study publication offers artists the chance to freely talk themselves about their practice. We know too little about how an artistic scene or a generation of artists coagulates, and art publications usually analyze the artistic object, without putting to much focus on processuality, thus alienating the artist even more to the local audience. Or, when it comes to performance art, in the context of financial precariousness, the process by which these artists have produced their works is mainly based on collaboration and moral support. So, Metaphor. Protest. Concept. is not the type of publication that simply covers the careers of some artists, but rather has the feeling of a round table discussion. The light conversational style with which these interviews were conducted keeps this lecture free from any academic or pompous character. No trace of stilted speech, but there is a dictionary of people, ideas and projects for any queries at the end of the book. Iulia Popovici and Raluca Voinea managed to grasp the very essence of it all, while maintaining a natural flow of discussion that translates into a very pleasant reading. The only thing I find the book to be lacking would be a few other relevant names: Ion Grigorescu, Geta Brătescu, or Teodor Graur, important artists who worked with performance before 1989, would certainly have a lot to say about that particular epoch; Mihai Lukacs, Vlad Basalici or the subREAL group are also absent. But perhaps this is an opportunity to begin the preparation of volume II.

POSTED BY

Marina Oprea

Marina Oprea (b.1989) lives and works in Bucharest and is the current editor of the online edition of Revista ARTA. She graduated The National University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, with a background i...

marinaoprea.com

Comments are closed here.