It took many years for the curator to become an established figure in Romania, and for their work to be acknowledged not just on the administrative level (curator as manager confusion) but also on the aesthetic, affective and political ones. I spoke to Anca Verona Mihuleț, one of our youngest professional curators, about her career so far, trying to understand the stakes of her work and the places in which a curator may act.

Let’s start with your university studies.

In 2004 I graduated from the Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj, majoring in History and Art History as part of the History and Philosophy faculty, and I was one of the few generations that were lucky enough to benefit from a double major. Although there was a lot of work involved, I’ve since appreciated the consistent information I acquired there; it helped me better navigate through all the artistic styles and understand the connections between them. I’ve realized how important studying history was in 2003. Moreover, the philosophy and aesthetics courses in college made this knowledge stick. Currently, there are a lot of curating courses, but this knowledge is crucial in understanding the depths when working with culture, when making the right selection.

After that, between 2004 and 2006, I attended the Art Theory masters program at the National University of Arts in Bucharest. It was coordinated by Ruxandra Demetrescu and Anca Oroveanu. It was a good time to study because they were specialists in theory and museum studies. I managed to observe and understand how museum theory was founded in the 19th century and how it evolved along side political and historical events.

Is this masters program still available? Which of your colleagues are still active today?

I don’t think the masters program has the same structure. When it comes to my colleagues, I think of Raluca Nestor – she was also specialized in new media or Olivia Niţiş. Most of the time, those taking practical courses would join us for certain theoretical courses.

Our work was applied to contemporary art, using local or international examples. The only thing that was missing during my studies in Bucharest was the fact that we had no guests artists during our seminars. We needed to see artists talk, see them in a more decentralized way, see exactly how they gather information in contemporary art.

Did you have a graduation project, did you organize an art show?

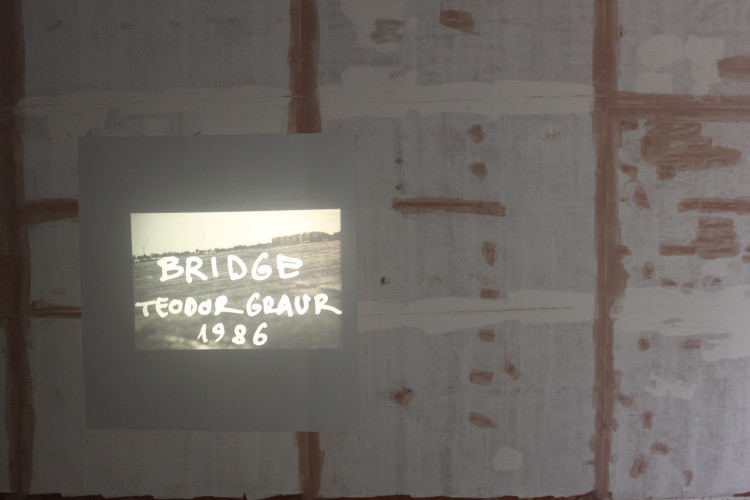

No, it was a purely theoretical project. We each picked a subject and wrote about it. Back then, I was studying theories about the city and I worked with a few artists who handled the city in a special way: Iosif Kiraly, Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, and Teodor Graur. On the other side, my diploma marked a particular moment in the evolution of how I felt about art. With the help of one of my professors, Vlad Ţoca, I presented a work on contemporary art written with the help of contemporary concepts. It was about the Supernova group in Cluj, formed by István László, Ciprian Mureșan and Cristi Pogăcean. It meant a lot to me to present this project; I was able to “tackle” contemporary concepts that were new to me in 2004 and I managed to build a complex bibliography. I was also consulting the internet, which was new at the time, so I found new information or I checked things that I couldn’t find in books.

Did you have a contemporary bibliography for your bachelor and masters programs?

During the university years we did not necessarily have access to contemporary authors in regard to the study of art history but I was able to get several books on theory from friends who were living abroad. During my masters, access to contemporary books was easier and more direct.

Did IDEA magazine help you in this regard?

I’ve worked with books published by IDEA and also used their magazine. Yet, my way of thinking wasn’t in the magazine pages – it was a bibliographic material that I treated objectively. In Cluj, it worked as a source of information for art history students – these were contemporary readings that were very handy and it was really useful for accumulating new ideas that would also say something about the world we live in.

Did you find anything similar in Bucharest?

In Bucharest I did all my reading at the library of NEC – New Europe College. A lot of what I read and summarized back then is still useful today.

Did you also study for a Ph.D.?

No and I don’t think I will any time soon. I think that working as a curator is practical enough. To study for a Ph.D., you need to discover something original and to take the necessary distance in order to analyze a curatorial method or exhibition format.

Did you start doing art shows since you were undergraduate?

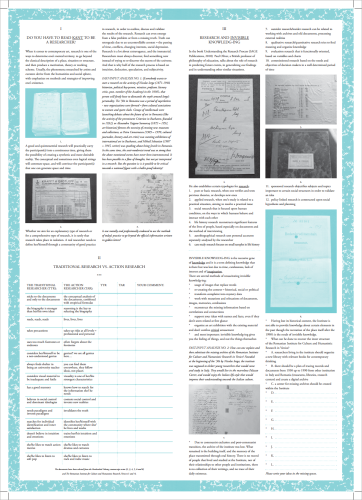

I wrote critical texts since back then. I slowly started to theorize my route and use specific instruments for theory. In 2004, the second part of my bachelor thesis was dedicated to curating – it was a study in nuce. I worked with a series of contemporary methods; for example, I conducted interviews, an unusual method for an art history program, in order to write about the specialists I was analyzing. I finished my thesis with two interviews – one with Mihai Pop, where I explored the direction he was taking Plan B Gallery, and one with Liviana Dan, whom I named “institutional curator”. Back then, to label things seemed pretty innocent, but it turned out those labels remained relevant.

I continued the collaboration with Liviana and in 2006, when the Brukenthal Museum was hosting a competition, I signed up and became a museographer. Liviana had already initiated a platform for contemporary art within the museum so we ended up working together at the Contemporary Art Gallery for seven years. We started in 2007, when Sibiu was the European Capital of Culture; over time, the gallery’s programs became more and more thematic. We worked with a yearly schedule that we prepared ahead of time even though we had no dedicated budget and a real support coming from the institution

You didn’t have a budget allocated by the institution?

It was a basic budget, no production included. After 2008, we were sponsored by Henkel for five years but this support was mostly directed towards promoting the gallery’s program. Whenever we hosted an art show, we had to work directly with the artist or curator in order to find a solution. Naturally, the museum had a structure that functioned as basic support: there was a space with regular opening hours, paid employees – it wasn’t an off space.

You hosted residencies at one point as well. Did you have a dedicated space?

It was a residency that we organized in collaboration with the Brukenthal Foundation. They had a space in Avrig, the summer palace of baron Brukenthal, which was cared for by the Evangelical Parish in Sibiu. They were interested in contemporary culture and together we organized a few residencies with international funding. This way, we could support artists for extended periods of time, up to 3 months.

We collaborated with foreign institutions for these residencies – The University in Geneva, The University in Kiel, Schafhof Freising – and with artists that were particularly interested in the landscape. The whole point of the residency was that the artists worked in a particular scenery, an elaborate baroque garden.

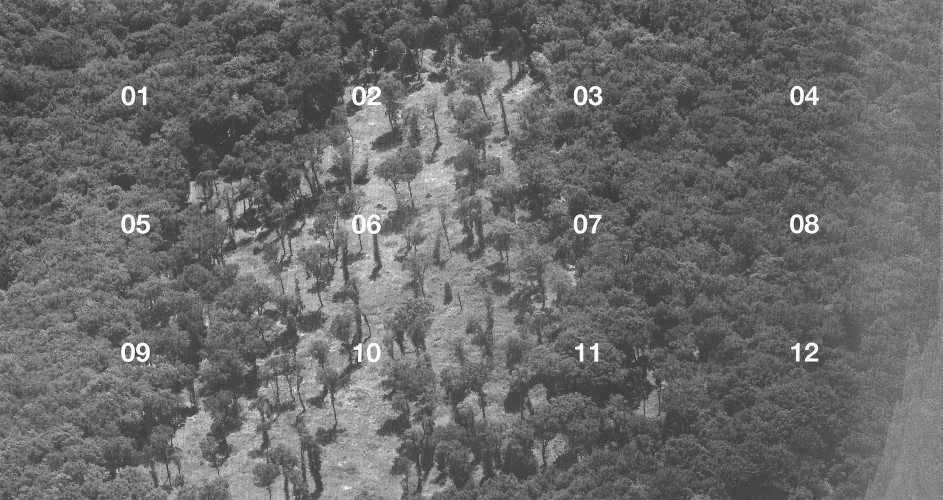

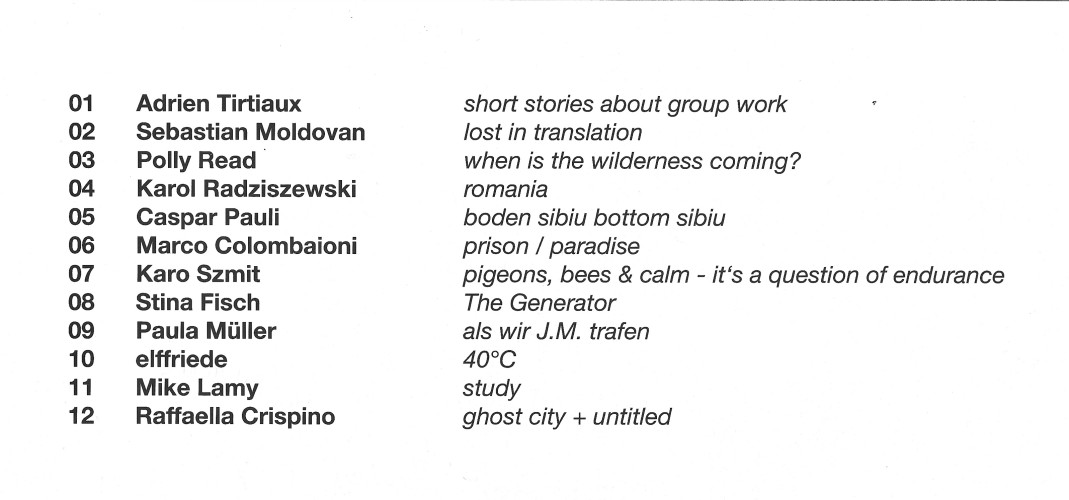

One of my favorite projects was Catching Passages in the summer of 2007, when the Contemporary Art Gallery collaborated with Casino Luxembourg for a residency based on an open call to which artists from all over Europe answered. 12 artists who worked with drawing and were inspired by landscape, by nature were selected by an international jury. They were 12 remarkable artists with whom we worked in a phenomenal way. They spent two weeks in Luxembourg where they prepared a project, then they came to Sibiu for another two weeks where they stayed in Piaţa Mică [the Little Square], in the city centre. The idea was that they observe the city – European Capital of Culture at the time – so that their experience wouldn’t be limited to just the idyllic retreat at Avrig. The Romanian participant was Sebastian Moldovan, who proposed the “hijacking” of the project: they had a big sum of money at hand for the production of the exhibition and Sebastian suggested they use this money to buy a piece of land in Romania, and come together as an association. But back then you couldn’t make such a transaction if you weren’t a Romanian citizen. It wasn’t democratic if only one member of the group, the Romanian citizen, had all the land. In the end, this land became fictitious: they took photographs of the Dumbrava Forest and made a giant tapestry of pixelated trees. The publication had 12 sections with 4 pages for each artist, and on the back of each intervention there was a piece of this forest. The visitors who took the book home could rebuild the image of the forest out of these 12 pieces. It was a project with a rare dynamic. A lot of artists, who at the time were very young or fresh graduates, were inspired by the ideas that sprung out of that fertile environment of strong and tenacious creators. They had a few mentors, of which I will mention Dan Perjovschi and Jonathan Meese. The latter organized a seminar followed by various discussions where the group analyzed ways to be combative.

Your collaboration with the Brukenthal Museum ended in 2013. Why?

The discrepancy between visions determines the aperture of new directions of action. It would be advisable to launch a broader discussion about the way the museum perceived the agenda of the gallery; there are several aspects that need to be analyzed individually in order to understand why the program of the Contemporary Art Gallery finished so abruptly. For commenting the relation to the institution a degree of exteriority is required, together with the perception of being other, different to the official institutional community, which only defends its own interests, as Manuel J. Borja-Villel puts it.

In 2013 I was working on the project for the Romanian Institute of Culture and Humanistic Research in Venice, as part of the Biennale. The project was related to art history, so in this sense, the museum was always a source of inspiration for me. It would have been ideal to create a relationship between the Brukenthal Museum and the institute in Venice, but this was not possible at that time. So I had to make a decision, to prove my loyalty to a context – in the end, the decision came naturally, since I wanted to work on the project intended for the Biennale.

Back then, besides MNAC, there were no other public contemporary art institutions.

Nothing this dedicated, no. The Contemporary Art Gallery of the Brukenthal Museum represented a very interesting model: a contemporary art gallery functioning in a classical museum.

I am asking because one of my interest points when conducting these interviews is to map the practices and ways of organization in Romanian contemporary art. I’ve heard numerous individual stories that I can’t really connect – for example, Brukenthal was renowned abroad, I knew who you were even though I hadn’t been living in Romania for over 6 years at the time and I wasn’t very connected to the scene either, nor did I know any of you personally. From afar it seemed like an idyllic situation in which the museum was supporting contemporary art.

This was due to the fact that Liviana and I were always careful to correctly present the artists’ works; we each supported artists from our generations, who we personally knew and closely worked with. A lot of the artists I worked with were good friends who I used to talk to about art and theory long before we actually started collaborating for exhibitions; even back in college we would discuss theories that are still relevant; back then, they were just taking shape. During my studies, curating was pretty cryptic and a power profession – few people had access to the type of curating that is now happening extensively.

It was the Szeemann model I suppose. Did you have any curatorial models in Romania?

You spoke about historic curators at some point. In the beginning, I had professional dialogues with two such curators. The ones with Liviana Dan had drawn me closer to this profession, since she was active since the 1980s and knew a lot of aspects regarding this profession. We became close because we worked together and shared the same office space for seven years. Then, there were the dialogues with Judit Angel, whom I met in 2006.

You’ve had numerous collaborations with other curators, like Diana Marincu. Besides that, you often work with a group of artists – Olivia Mihălțianu, Apparatus 22, Sebastian Moldovan – who take on different roles depending on the project. At one point, there is this idea of a “theoretical input” from Olivia.

Yes, these collaborations are very dear to me. I started working closely with Diana in 2014, when we were preparing the project that is now drawing to an end at MNAC – The National Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, The White Dot and The Black Cube. Nevertheless, our collaboration actually started somewhere in 2009.

About my connection with the artists you mentioned, a friend recently told me I’m a sort of Quentin Tarantino of curators: I often work with the same artists and I have a soundtrack in mind that is vital, becoming a real source of inspiration. The research project Situated Knowledge: I Follow Rivers of Thoughts has its title inspired by a song by Lykke Li that I used to listen to obsessively when I was working on this topic. Sound and music are some of the most personal vessels of communication.

In certain cases, I prefer working with the same artists because we already have a mutual understanding – of a moment, a phenomenon and a practice – which translates into respect for the job each of us does. We go far with our ideas because they don’t develop just when we’re all sitting at the same table, but also when we’re on our own, working somewhere else; when we come together, these ideas have such a tremendous force that we make them real.

That’s a good comparison, the one with the director – for example I am thinking of Fassbinder’s movies, where you see the same actors; sometimes they’re the good guys, other times they’re the bad guys. This also reminds me of the short story you wrote for the publication Reflection Center for Suspended Histories. I also think this is a good time to ask you about the importance of text in your curatorial work.

Yes, I’ve published texts since the early 2000s. Articles in Praesens magazine come to mind, where Judit Angel was editor, or Projektgruppe’s magazine in Hamburg called Journal for Northeast Issues. Geography is an essential factor that has followed me over time. It was easy for me to send them a few theoretical texts and interviews that explored their themes. They also invited me to their reading room in Hamburg, where they organized public discussions also referring to what was going on in Romania in the early 2000s.

When I was working with Liviana Dan, we had the practice of writing texts together. There was a special moment when we wrote a text because we really did it together: each of us would bring a certain research, corpus, piece of writing, and when we put them all together, the result was truly beautiful. This was the same practice Diana Marincu and I used when preparing the curatorial texts for the project The White Dot and The Black Cube.

I find it impossible not to be inspired by literature. The literary element is usually canceled out in texts written by curators – a curatorial text is so welded that it cannot be compared to a literary one. At the end of the day, even if you get inspired by fiction, you still can’t make an art text sound like a work of fiction. But I always experiment with writing and try to find new ways to write. Back in the day, I used to write in an academic way, it was constraining and I stopped doing it. Yet it is something I have been practicing along with another collaborator, Patrick Flores, who is following this type of approach in his writing. Whenever I work with him, even if the text corpus is academic, I feel free in the act of writing.

The text you mentioned was indeed interesting, the one for the publication Reflection Center for Suspended Histories. An Attempt, which accompanied our 2013 exhibition at the Venice Biennale. In this case, I was innovative with both texts I prepared. The first was a guide I made after I researched various “newspaper” type of publications from the 17th and 18th century; the text disclosed the geographic position: it started with Titian’s garden at Fondamente Nuove in Venice, then it would guide you through space and time until you arrived in the exhibition, which was in itself a geographic position. I introduced the idea of a publication as the type that goes around the room, from then on it all dilutes until you are left with the exhibition guide and the three ways of guiding or being a guide in that exhibition. I really like how I was able to achieve this thing. In my second text, the one in the catalogue, I took a short story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Mazarin Stone, and interposed it in the exhibition format. I knew Conan Doyle’s stories quite well so it was easy to find this one that perfectly fit everything in the show: the heavy 19th century atmosphere, the links between people and places … I transformed the characters in the art show into characters from the story. It was challenging to make an iconographic description while the publication worked as a iconological description – interpreting each work from various perspectives.

I admit I was surprised when I read that story. I came into contact with your way of writing during the MNAC exhibition I used as an example for the Critical Nature workshop hosted by our magazine. Diana and yourself told us – me and the students – that text is very important for you, but the essay which accompanied the exhibition seemed a classic curatorial text to me, with a lot of references and a display of terms. After discovering your playful side, I tried to understand what you are actually interested in when you write – and what interests you have when you are curating.

When I follow a curatorial work, I usually pay attention to the political dimension, the response to context, the positioning – when I first came into contact with your project at MNAC, I had the feeling that your stance was somehow in retreat, but after analyzing the rest of your shows, I am starting to see the bigger picture. So the question still stands – what is a political stance? I am also asking because nowadays it feels like the privileged position in contemporary art – and the one that is the easiest to get behind – is that of the curator. I feel like the artist only intervenes in a punctual way and it is more difficult to see the context around him, while the curator creates contexts – I think this is in fact the definition of the curator. The discussion is around the kind of contexts you can create.

I often think that you can’t consciously assume a political stance as a cultural agent – this stance forms in time without you even knowing it. I find it hard to control. Just like you, I ask myself these questions every day; sometimes you can isolate yourself from the somewhat strange context we all live in, but then I have realized that in order to be political per se, you also need the required language and experience. So I come back to an old idea of mine, from when I was working with artists on small guerrilla projects that were totally anonymous: that’s the closest I’ve ever felt to a political activity because the anonymity and that punctual action had a political layer that changed something then and there, they brought awareness for a clearly defined group of people.

When you perform a guerrilla action, I don’t think it matters that much if the means are artistic or not, or if you’re an artist or not.

That’s exactly what I liked about it, that it didn’t matter. A project that inspired me, and about which I wrote a few years ago, was that of an artist from Lebanon, Rana Hamadeh, who moved to the Netherlands and started questioning her identity. As a consequence, she filled an entire street with the word “wolf” – she saw the wolf as an animal who is not accepted, even though it is important. I thought that was a powerful gesture based on a real experience. The artist pursued a traditional art university in Lebanon. When she arrived in the Netherlands, she realized her potential and the projects she makes now are truly political. If I were to define a political artist, I would refer to Rana: she does not exoticize herself, she talks about her own existence as a healing process. I think that when someone wants to be political, they also have to be personal. We encounter this personal dimension in art; art is a place where we must talk about our problems because, in fact, they are everybody’s problems. An artist also uses a visual medium, a rich vocabulary, thus he can explain certain situations. This is how I see the political: when someone talks about themselves and their context in a sincere and representative way. After all, I think you also need a background that allows you to step out of your comfort zone, your studio – in order to record the tension, to inform yourself.

Still, I’ve never seen you curate explicitly political art. This is obviously something you’ve decided.

Yes, totally. If I were to think of a textbook type of political gesture, the RoArchive exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery in 2009 comes to mind, a project curated by Raluca Nestor. It was RoArchive‘s first presentation in a museum environment. Because the exhibition was opening on December 20th, the curatorial display also integrated photographs by Mircea Stănescu with people who had died in Sibiu during the Romanian Revolution, in 1989. Those images, those bodies introduced in the context of the RoArchive footage, stayed with me precisely because I perceived this art show as a political gesture. Any political action stays with you.

On the other hand, I don’t agree with Didi-Huberman’s method of addressing the violence within specific types of imagery. Maybe it used to work a few years ago, but now it’s just a form of free violence, a spectacle I guess.

I can’t tell just how relevant the theories on the spectacle are anymore.

They’re passé, but no matter if we accept it or not, we do live in a spectacle type of society. In art, visibility automatically imposes this state.

Precisely why I think we have to be even more responsible, because we chose to work in an environment that represents the place of oppression itself: the visible is the place where oppression and manipulation take place. This decision makes us accomplices, but we can’t just leave, the only ones left in this field would be those who would instrumentalize it.

I’ve had long talks with Rana Hamadeh about what it means to be political. I always think about the Romanian context which is hyper-politicized. I’ve decided to stop being political and to find the missing piece – I often joined the aesthetic field, personal decisions or histories that have a political stem.

When I mentioned earlier that art can create self-sustaining worlds, I was also thinking whether art’s role shouldn’t be that of asking questions that aren’t asked. Specific political questions are already asked in specialized political contexts. I can’t tell whether those who engage in art can ask questions in this same manner, or answer them with these same tools – perhaps it is worth asking the questions in the background, or the little questions hiding behind the big question.

I think you need to break this question, like when you’re doing a syntactic analysis. It is hard to make an analysis if you are strongly engaged in a system, but an artistic thinker has the potential to make such an analysis due to the diverse means they are using. This also involves role play: when you work on a project, you should have a stance that should also migrate around a circle or a question. A perfect example is Irina Botea Bucan’s work, which you can see as part of her personal show at MNAC till March 26th: she collected numerous “suspended histories” – unknown – and in their pursuit, she discovered other questions, that you can’t really tell where it all ends…

It reminds me of Olivia Mihălțianu, I wrote a text about her in the summer of 2016. What I found to be valuable in her approach was precisely this longue durée that I am starting to understand also as stemming from your decadelong collaboration.

Olivia was also a colleague during my masters. We got close back then due to our mutual interest in fashion, an area in which I was looking for a new meaning. She introduced me to the nucleus of the Apparatus 22 group, Dragoș and Erika Olea who were working for the fashion label Rozalb de Mura at the time. That’s how our group extended and we started to intensively discuss things among ourselves. It resulted in our first project, Anyone but me, Anywhere but here, which we presented at the Contemporary Art Gallery of the Brukenthal Museum in the fall of 2008 and which is still one of my dearest projects. I built it together with Olivia and Rozalb de Mura under the influence of everything we’d seen that year: Cy Twombly’s exhibition at Tate Modern, the museum’s archive and a lot of other things that made that art show so consistent. On another side, the project ideas stemming from the long-term collaboration with the collective Apparatus 22 have emphasized the ritual-like and imaginative dimension of my curatorial parkour.

What impressed me about Olivia is also the fact that her approach is 100% artistic – she is a professional artist. And you are a professional curator – you haven’t hybridized your practice in any way.

It’s hard to self-evaluate, but I would say that I generally try not to stray very far from my professional path. I think the personal trajectory is needed in any profession, it makes us aware of our temporary presence on this earth, it gives us consistency and prevents us from self-instrumentalization. For me, curating was also a way of learning about the world, of understanding it. In art, you learn to learn better.

When I said you did not hybridize your practice I also meant that your curatorial take focuses on the exhibition.

Yes, I am interested in the exhibition technique and the way in which you exhibit an idea, because an art show means so much more than that. I also see a ritualistic dimension: the way in which you prepare the show, the context, the ways of finding a space. Sometimes it takes years for me to choose a place for an art show, to understand that something needs to be done there. Why make something in a place where there is no point in doing anything?

When you talk about a ritual when it comes to choosing the context, I’m thinking you don’t see your intervention in the context as just one problem solved, but that you also take into account other aspects: the aesthetics, the emotional, the chemistry between your project and the context.

A classic example of working with the context was the art show I prepared last year for the Vargas Museum in Manila. My collaboration with Patrick Flores spreads over several years in which we talked about art history; he is a connoisseur of Southeast Asian art history and I sometimes used his methods to try to understand what was happening in the Southeast of Europe between 2002-2003. The first big art shows dedicated to art from the region were already taking place back then. I created a mental context for myself which was based on the fact that, since I was from that region, I must support the local artists, work with them – it was about solidarity. I didn’t want any fancy institutions, but an exchange of ideas – to build and discuss, to create projects that are specific for our generation. That was the first time I set a clear locus for myself.

For the show at the Vargas Museum, I worked with the specific context of the late 1980s – early 1990s in Romania. I selected works by artists that I’ve always considered important for that period and I transported them in the Manila context, at a university museum. During the exhibition, the students took part in an art critique workshop and they raised all sorts of questions about Manila and its political context. I wasn’t expecting this. I noticed they used the word “context” in many of their questions, which was obviously different than what I understood when I was referring to “the context” – their interrogation was based on the dictatorial regime that imposed a position. In any case, this made me think of dislocation: by dislocating the works of Romanian artists from their natural frame, they gained relevance in that new context. If I would have curated the same art show in Romania, it wouldn’t have necessarily had the same relevance because all those artists have become canonical – the show would have been a simple repetition in an old history. But in Manila, the dislocation made me aware of the notion of “a context” – the one I entered and the one I came from. I’ve also worked with Patrick on the idea of dislocation during the two exhibitions South by Southeast at the Osage Art Foundation in Hong Kong and the Guangdong Times Museum in Guangzhou, China.

You’ve also received the Igor Zabel Award for your involvement in the cultural life of Southeastern Europe.

During that “period of solidarity” in 2002, I was thinking it would be interesting to bring artists from our area in the Western context and demonstrate the positive difference, to bring the west to see the east. This happened eventually – Western artists have been inspired by Easterners, using their methods (low budget platforms, for example).

South by Southeast is a political project because we are talking about common place, the Southeast axis opposing the Northwest and about the need to reinterpret geo-cultural paradigms. We brought localization to the table, but also the aesthetic potential of Eastern art produced in the Southeast without any kind of exoticizing.

There is a relevant text for our discussion in the catalogue of the exhibition South by Southeast. In this text, there is a reference to an article by Suzana Milevska, who wanted to make a show in 1998 about art in Southeastern Europe entitled Honey and Blood, a phrase inspired by the origin of the toponym “The Balkans” – in Turkish, “bal” means “honey” and “kan” means “blood”. She was refused by an art space in Sweden, where she initially put forward the project, only to find, five years later, another show with a similar title, Blood and Honey, curated by Harald Szeemann.

You said that the West picked up low budget methods from the East, but two other phenomena took place at the same time: the West became increasingly precarious, especially the cultural area, which turned the discourse on peripheries into a seductive one – as a consequence, it was appropriated and instrumentalized by the West.

During one of the first curatorial trips in the East, organized by deAppel in the 1970s, the group would stop in Hungary, because it was impossible to access the countries located further East. In the book Reflection Center for Suspended Histories. An Attempt, the texts talk about this history of rapprochement between the West and Romania. During the ‘1920s, at the peak of modernism, Romania was just as developed as the Western countries – in one of the exhibitions mentioned in the book, the curators introduced high-end ceramic works, that were abstractizing the popular Romanian motifs. Then there’s the discrepancy created by communism, and since the book is about suspended history, in the second chapter Monika Wucher, an art historian in Hamburg, describes her first trip in Eastern Europe: from Hungary, where she was studying, she tried to get in Romania because she was interested to see works by Hans Mattis-Teutsch in Brașov. She had to stop at the Hungarian border because the Romanian space was closed, you couldn’t make your way in. What I liked about her, regarding this desire to not exoticize the Southeast, was the fact that she learned Hungarian to better understand the cultural environment in Hungary. Language is an entry point – I believe that any honest researcher has to learn the language of the territory they are working in, to understand the mental collective, not to manipulate or appropriate it. In the end, the job of a cultural worker is limited because you cannot hold encyclopaedic knowledge, you have to limit yourself – and I come back to context because now I can better define it: context is limiting yourself to that one route you can be loyal to.

Ștefan Tiron told me about the curatorial excursions of the 2000s, when Romania was becoming an interesting place and various institutions such as Soros’ foundation or ProHelvetica started to finance local projects, they were attempting to build histories, to find dissidence.

I was in the university back then and if such a group would visit Cluj, everyone was alert and careful about what to show and demonstrate in order to be seen. Mladen Stilinović talks about these moments in which foreign curators traveled to an Eastern country and influenced the cultural landscape.

I read an interesting text by Marga van Mechelen in which she describes the tense atmosphere of Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1970s, which was the basis for two important art shows presenting Eastern artists – one in Warsaw in 1978, “I AM”, and another one in Amsterdam, in 1979, called “Works and Words”. Van Mechelen considers the latter a semi-failure due to the fact that the Eastern artists fought to be perceived as individuals and not the exponents of a regional reality.

I think the most frustrating thing, after you spent so much time in the West and managed to solve your identity issues, is when you come back home and notice the lack of courage when it comes to positioning oneself differently than in regard to the West. Up to a point, you cannot escape this measuring up, because it would mean denying the whole Western project, which is to be the cultural model par excellence. But you would expect to see such stances in art, especially: not political in the sense of finding solutions, but political in the sense of imagination.

Well said, politics as imagination – this would be ideal even for governing a country. If we think about the first models of government during the Renaissance, everything was seen as a utopia – it was, in fact, imagination.

As a cultural worker, I can’t deny the temptation of entering politics, seeing as the general feeling is that our activity is a kind of artifice or a parergon.

Right now, I don’t necessarily believe in the edifying force of art shows. I see the educational potential of art – this just came to me, it was the elephant in the room. In an exhibition you can bring up certain issues and lately I’ve been trying to identify the groups destined for such discussions – this is how I got to children and young people. When I was in the Philippines, one of my friends brought her students to see the show; they were shy at first; after we started to interact, I was amazed by what was hiding in each person’s mind and how important this persuasive education is in very small groups. I am starting to have ideas in this sense. There’s a need for an institution to bridge the gap between the museum and the people, a special office that handles cultural education, that has nothing to do with traditional education. Specialists are needed in order to create strategies for people to become active in their own existences. This morning I saw a children’s play at Apollo111, “Carina finds her way back home”, about a girl from a rigid family that excessively protects her. The girl gets lost in Bucharest and a cat helps her read the signs on the streets and find her way home. I believe that you can teach visitors to read the signs of an exhibition as well, lead them to realization – and the cultural mediator is the one who explains everything in a playful manner; they can also make use of everyone’s mental structuralism in order to apply the principles of inclusive education.

I still find this to be a complicated question: whether education is meant to format, to transform one in an obedient subject, or to liberate and individualize. I wouldn’t eliminate this from our discussion on art education.

I think that education can offer the reading clues for the parallel processes all around us; education equally means formatting, liberation and individualization. Now is the right time for profound reforms in education and culture, for major changes that are not under the influence of external factors. Technology should become an integrated part of the educational process in a way that involves sensitivity but also rationality. Education, no matter the age or social conditions, should bring about the transformation that is much needed today.

This is the transcript of a live conversation in January 2017.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.