The exhibition “Eco-Cultural Tides – Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord”, curated by Mirela Stoeac-Vlăduți at the contemporary art gallery META Spațiu in Timișoara, maps the cultural and ecological layers of the Danube and Oslofjord – two bodies of water with distinct histories, but interconnected by the flows of memory, ecology and social change. The exhibition presents these waterscapes as archaeological sites, and artists Kristin Bergaust, Cosmin Haiaș, Alex Mirutziu, Marina Oprea and Alexis Parra (Pucho) identify the sediments of history, artifacts of human intervention, and power structures, as well as invisible and submerged narratives.

The exhibition is just one stage of a larger transdisciplinary research project, which was based on the collaboration between art and science, including field research in the Danube Gorge area and an artist residency in Oslo. The artists had the opportunity to collaborate closely with specialists from various fields, exploring topics such as the exploitation of natural resources and the ecological impact on these landscapes, the cultural heritage of the Oslofjord and the Danube Gorges, methods of preserving collective memory, etc.

The curatorial and artistic research is centered around the mythology of the two natural landscapes that are seen as living spaces, constantly evolving and in constant negotiation. It would be unfair to talk about the Danube and the Oslo Fjord only in the familiar geographical and economic terms. Beyond these anthropocentric perspectives that impoverish their history and significance lie marginalized communities, forgotten migratory flows, ecological shifts, the ruins of exploitation and shipwrecked histories. In his book Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (1984), British cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove argues that landscapes should be understood as cultural palimpsests, shaped by power, ideology and historical processes, rather than as neutral and untouched spaces. The exhibition adopts the concept of deep mapping, developed by Cosgrove, an artistic and scientific method of integrating history, memory, mythology, ecology, and human and non-human experience to shape a more complex and relational understanding of a place.

Initiated in collaboration with partners in Norway, the project aims to adopt a new eco-cultural framework, outside the boundaries of anthropocentrism, in which we relate to the Danube as more than a natural resource. Artist, researcher and professor Kristin Bergaust initiated the Oslofjord Ecologies project in Norway – an interdisciplinary based artistic research project with the goal of creating new artistic practices and new models of thinking that explore the crises of the past and present, imagining more sustainable ways of living together for the future. The endeavor centered around the Oslo Fjord, the social, economic, cultural and ecological life on its coast, both above and below the water. Thus, inspired by the success of the Oslofjord Ecologies project, Eco-cultural tides aims to develop a new vocabulary of relating to the Danube, to adopt and promote a new way of relating – more conscious and engaged.

From the bloodiest border in Europe and a forbidden landscape under communism, to the sinking of Ada Kaleh Island and the construction of the Iron Gates I and II Hydropower and Navigation System, the Danube continues to be seen today only as a natural, energetic and economic resource. However, the Danube remains an important conduit of history, a liquid archive of the past, witness to political, ecological and cultural transformations. “What can never be taken from you? What will you become in 50, 1000, 2000, 5000 years?” – wonders curator Mirela Stoeac-Vlăduți, addressing the Danube in the journal she kept throughout the project. Confronted with this intimate journal before stepping into the exhibition proper, we are taken through the stages of the project and the curatorial approach, through the discussions held both on the fjord coast in Oslo and during walks along the Danube, through the artists’ individual interactions with the natural landscapes, etc. This journal, a book-object filled with the curator’s intimate thoughts and reflections, Polaroids of the team of artists and photographs of details of natural elements, anticipates the intimate and epistolary framework of the exhibition.

The exhibition thus opens as a collective letter of reconciliation and closeness, initiating an ongoing dialog with the Danube itself. Each work in the exhibition represents personal alternative cartographies of the Danube and the Oslofjord, encapsulating intimate experiences and layered multidimensional narratives that encompass both the sediments of history and speculative futures.

Artist Alexis Parra (Pucho) approaches the Danube and Oslofjord as vast, liquid archives that conceal and reveal traces of human activity. In Fishing Report, the artist recovers and repurposes corroded iron objects found in the depths of the water, which become artifacts of oblivion, material ghosts of unseen stories. Water, in Parra’s vision, is both a guardian of memory and a force of entropy, eroding human remains while paradoxically preserving them in layers of sediment and corrosion, revealing the fragility of human presence in the face of natural forces. His approach is neither purely documentary nor nostalgic. Rather, Fishing report functions as a speculative, non-linear mapping of history, questioning the fluid nature of memory, which is always in a process of reappearing and reinterpreting.

The process of memory formation and preservation is further explored and developed by artist Marina Oprea. In the installation Where lucid waters flow, the artist introduces us to the landscapes of two bodies of water: The Danube and the Oslofjord, presenting a video essay, film stills and site-specific found objects, which she has incorporated into molecular spheres of ‘water’. But these organic and artificial assemblages seem to acquire their own ontology and generate a new landscape. By suspending the organic elements in synthetic materials (epoxy resin), the artist examines the tension between conservation and transformation, asking whether archiving does not inherently entail alteration of the conserved object. Marina Oprea also intervenes on photographs with these “water molecules” that function as lenses, creating new centers of interest, ultimately shifting the focus from human constructions to natural elements, inviting a comprehensive vision and a detachment from the anthropocentric perspective. The video essay, which presents an intimate, almost dreamlike meditation, extends this discourse, through a continuous flow of thoughts and fragments of water, investigating the tensions between preservation and decay, past and present, human and nonhuman time. The work mimics the echoing rhythms of water itself – flowing, eroding, reshaping – revealing how memory, identity and landscape dissolve and reconfigure themselves ceaselessly.

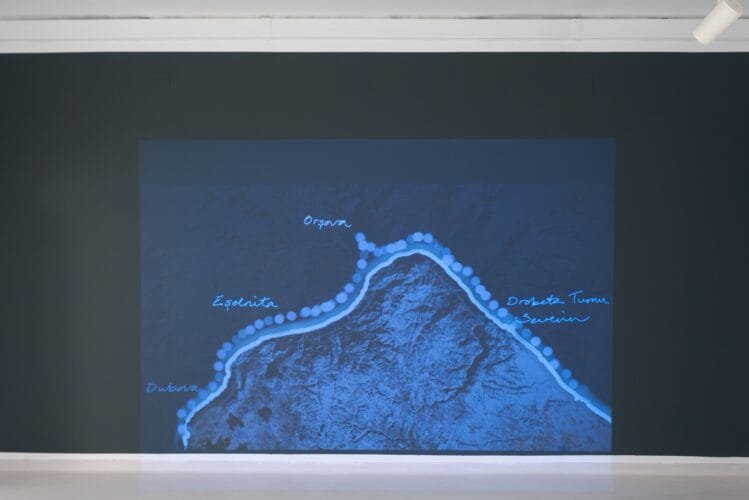

In her video essay Rivers of many names, Kristin Bergaust presents a poetic juxtaposition of archival material, moving images and soundscapes, evoking the Danube as a space of unresolved conflicts, an ecosystem where past and future coexist, where traces of migration, industrialization and climate crisis are sedimented in layers both visible and invisible. The Danube’s multiple names – derived from different cultures and languages – show the fluidity of its identity. By visualizing the sinking of the old Orșova, the disappearance of meadow biotopes, endangered fish species and, last but not least, the displacement of local people’s houses, the artist takes us through the layers of history and the complex dimensions of crises. Kristin Bergaust reiterates the need for a comprehensive and inclusive approach, whereby every element both human and non-human is equally considered, ultimately summing up Donna Haraway’s call for direct engagement with the complexities of the contemporary world without seeking simplistic solutions. Donna Haraway introduced the concept of staying with the problem in her book Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2016) as an alternative to anthropocentric thinking and the simplistic solutions identified for the ecological crisis. Staying with the problem entails a tentacular and porous way of thinking through staying in complexity, learning to live with global crises in a responsible and relational way, without placing the human on a superior tier.

Alex Mirutziu expands the artistic discourse and moves into another, more intimate and deeper dimension. The video work Dump Cinema introduces us into the territory of mental ecology, as described by Felix Guattari in The Three Ecologies (1989), where the river becomes a performative entity of questioning identity, distortion of perception and fluidity of consciousness. The soundscape, punctuated by guttural voices and a discontinuous rhythm of images, induces a sense of dislocation, a state of suspension that undermines the viewer’s certainties and defies logic and linear narrative. By aligning the queer body with the incessant movement of the river, Mirutziu looks beyond the weight of all rigid categories, be they gender, sexual or even social, and emphasizes the impossibility of a definitive fixation of the self. Researcher Astrida Neimanis writes in her book Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology (2016) “We are all bodies of water. In fact, paying attention to hydrological cycles presents a rather queer notion: water is evidently both finite and inexhaustible; both the same and always becoming different, too.” [1]

Astrida Neimanis sees water not just as a physical element, but as a conceptual and physical metaphor for identity shaping and liberation, a medium of connection between bodies, history and memory. By introducing the concept of hydro-feminism, Neimanis challenges the notion of a circumscribed and autonomous self, suggesting instead that identity is relational, porous and deeply connected to natural and social ecologies. Ultimately, Alex Mirutziu’s work is a meditation on the fluidization of identity outside of any mechanisms of social control.

If Alex Mirutziu tackles the limits of the subconscious and the fluidity of identity, artist Cosmin Haiaș confronts us with our own future consciousness, in which mental ecology is no longer framed within the limits of human perception, but is found at the intersection of memory, technology and nature. The work Fish & (Micro)chips consists of a series of luminescent panels that merge the organic with the artificial, encapsulating the geological traces, vegetation and chromatic essences of both the Danube and the Oslo Fjord. Haiaș examines the relationship between technology, memory and perception, envisioning a future in which the natural and the artificial merge and become a whole. The work represents a speculative archiving of landscape, where natural elements are preserved in synthetic materials and databases, interrogating the ways in which the memory of a place is transformed when transposed into an artificial or even virtual environment.

The exhibition “Eco-Cultural Tides – Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord” is an exercise in memory, retrieval and revisiting one’s own histories and interactions with the natural landscape. Through diverse approaches, from deep mapping to speculative archiving, the artists reimagine the Danube and Oslo Fjord as living archives, where the artifacts of the past intertwine with the uncertainties of the future. Caught up in a world of overlapping ecological, social, political and personal crises, Eco-Cultural Tides does not attempt to offer simplistic solutions, but rather creates a space of questioning, reflection and dialog, as well as listening and coexistence.

The exhibition “Eco-Cultural Tides – Submerged Narratives of the Danube and Oslo Fjord”, curated by Mirela Stoeac-Vlăduți, with artists Kristin Bergaust, Cosmin Haiaș, Alex Mirutziu, Marina Oprea and Alexis Parra (Pucho), took place at META Spațiu in Timișoara during January 31st – March 22nd 2025.

[1] Neimanis, Astrida. „Posthuman Gestationality: Luce Irigaray and Water’s Queer Repetitions.” in Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, p. 66. Environmental Cultures. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

POSTED BY

Marina Paladi

Marina Paladi is from The Republic of Moldova and is a master's student in Heritage, Restoration and Curation Department at the Faculty of Arts and Design, West University of Timișoara. She is intere...

Comments are closed here.