In the summer of 2018, the mayoral election results in Chișinău were voided by the Moldovan Supreme Court. The judges who made the decision were likely friends of oligarch Vlad Pahotniuc. This sparked numerous protests, initiated both by the opposing parties as well as by independent, grassroots movements. One of the most interesting groups that made its entrance into the public sphere was #occupyguguta, also known as #protestpermantent. The activists around OG – writers, poets, architects, economists, artists, journalists, political analysts – placed themselves in the ideological lineage of occupy-type movements. “Guguță” was the name of a café from the Public Garden (Grădina Publică), a modernist building which used to be a popular social space, named after the protagonist of a series of children’s stories written by Spiridon Vangheli. In the original version, Guguță was something of a local superhero with supernatural powers. Unfortunately, Vangheli recently rewrote the stories, making Guguță into a religious child.

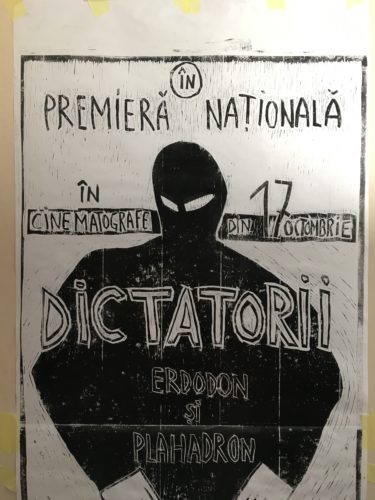

In 2018, the Guguță café was under threat of demolition, having been illegally privatized – together with many other public spaces, especially cultural ones – by companies connected to the same oligarch Vlad Plahotniuc. OG activitsts established a camp around the café, staging dozens of public actions in Chișinău as well as in other cities. OG began publishing a newspaper – “Protest permanent” – writing petitions, organizing actions, and editing books. Many of the happenings they did between 2018 and 2019 were among the most interesting action pieces from the Republic of Moldova – like Aleea Clasicelor (Alley of Classics), the poster series titled Dictatorii (The Dictators), or the numerous phantom tents from the Public Garden. These were actions I knew had to be written about and shown to the world. The works were most often collaborations, collective art pieces. I was however curious to unravel the thread of at least some of them, and so I met artist Victor Ciobanu, who told me about his contribution to #occupyguguta and #protestpermanent. Unexpectedly, the topic I was most interested in – the connection between art and politics in Ciobanu’s art praxis – turned out to be just a gateway into a discussion about the fragility of our bodies, and especially of the artist’s body.

When and how did your need to engage politically through art come about?

Since I was little. Around 6th or 7th grade. I was in secondary school at the arts high school. At that time there were some massive protests in Chișinău, some organized by students. Even though I didn’t really understand what was going on, I could feel a wind of change. Change was necessary. I was craving it. It was literally a palpable collective impulse. I took part in the protest alongside many others. As they say, it’s because of the collective that the student hanged himself. But my participation in the protests did not yet reflect in my art – perhaps only in a vague and unconscious manner. I started working with photography, for instance. I became interested in documenting events and how they may be reflected and retained in the collective memory.

Then, in high school – “Romulus Ladea” in Cluj – I was faced with discrimination. On the one hand I had the same rights as the local students, but on the other I was considered an inferior species. I was from Bessarabia, so I was seen as less smart, less intellectually gifted, basically a country kid.

What happened exactly?

It’s as if my roommates and I were speaking the same language, but different words. Our interactions would end in squabbles that then turned into discriminatory jokes. I was being reproached for many things. I was often asked for instance what I was doing studying in Romania: why hadn’t I stayed in Moldova?

Painting was my only means of responding to these questions and expressing myself. I was a better painter than the other students. I discovered it was my strength. Emphasizing the quality of my painting was a means for me to prove to everyone else that I was at least as good as them. I got better grades, received praise, was given as an example. My works were talked about and showed to other students. Some were selected for various exhibitions. I wasn’t working with complex subjects, rather with simple things. Being one step ahead of everyone else became for me a means of protest, of reclaiming personal ground.

I began consciously working with social topics when I was a student at the Faculty of Arts in Chișinău. One of my first such projects was about the absurdly low salaries In the Republic of Moldova and of the inadequate welfare system. I come from a peasant family. My parents couldn’t afford to pay my rent or keep me in school. My studies were somewhat limited by this. I was exempt from paying for my dorm. I also had a scholarship, which was so small it was as good as nothing. Anyway, I was in my second year, in 2006, when I got the idea to make a series of tapestries illustrating the figures connected to various types of welfare, starting with my scholarship, which was a kind of welfare, then with what they offer to mothers with small children, pensions – ridiculous in terms of financial support, as they could cover only a fraction of one’s living costs. There had to be ten of them. I thought about weaving into the tapestry the percentage covered by welfare of people’s actual necessary costs of living. It would have been a reflection on the period’s economy as well as a disheartening welfare report. I imagined the designs could even be sent to a carpet factory for production. They would have then reached our homes and become lessons in civic education. My goal was to stop focusing on traditional content and work with new topics and different kinds of visual content. Something that would truly reflect current issues. But my professor told me it was too sophisticated. That 10 was too much, that it should only be one piece. I was therefore forced to compress everything into a single object. That’s how Roșu de ochi [Eye-Red] came about.

But Roșu de ochi became more than some condensed statistics. If one is told they may bring to a protest not ten slogans but one that should synthesize all ten, then you won’t get one compressed slogan, but something completely different. I was sent into an area of reflection. I immersed myself in a game of physiological and spiritual recycling. A meditation on… charms. If I couldn’t change reality (yet), I thought I’d appeal to other strategies of making things right, strategies that are maybe more subtle and less common in art. I was fascinated by the basic unit making up the carpet – the woolen thread – an organic material grown on living, sacrificable bodies, then sheared off, teased, woven into a strand, all before being dyed. It’s a whole set of practices, oftentimes done manually, that become imbued in the material itself, together with the emotions of the people working it. Woolen threads are therefore a very complex material. Weaving them together means combining individual worlds. It’s no wonder that weaving is one of the most popular metaphors in talking about human collectivities or even big cities. I started by collecting old carpets. I washed and unwove them. I also did a bit of repainting. And, at the end, I began weaving a new work out of the resulting threads. Old recycled wool was a means of bringing feelings and stories into the public space. They were the shadows of artists from the past. Now they are forgotten, but perhaps we all share in this precarity.

What does Roșu de ochi mean? Is the title a wordplay from “deochi” (evil eye)?

The carpet is a visual charm. It’s an exercise in imagination that I wanted to offer everyone interacting with the piece. The dominant color is pink, not red. It is a risky color for visual artists. Many just ignore it or use it very sparsely. By chance I had found a generous supply of pink wool. In Orheiul Vechi I med baba Jenea, an old carpet weaver who had a lot of it. She was the one who determined the color. She passed away, but her wool has become part of my charm, so one can say she hasn’t died completely. Then there are the angled eyes that break the form and fire up your imagination. These eyes look like fish and oysters. It’s a brutal weave made from very thick and very thin threads.

After this how did your practice as an artist intersect with political engagement?

Working on Roșu de ochi, I became interested in video art. In fact, I filmed the weaving process, which was then showcased with the work. After college I got more into video. I made a series of works – investigations into, or maybe just video diary notes on, Bessarabian video art and cinema, focusing on new releases as well as on the barrenness of the contemporary cinema landscape, which was relatively prosperous under the USSR. Together with Marin Turea we pitched an idea for a show to a private TV network. It was to be called Cinestezia. What followed was half a year of weekly reports, obviously under a tight budget. I realized from working there that Moldovan television is run by crooks. They don’t care about the content of the program. All they see are opportunities for political propaganda.

When did your kidney pain start?

Around seven years ago. But that’s not a sign.

What counts as a sign that your kidneys are failing?

Water build-up in the body. Fatigue in the legs. Dental problems. Hair loss. High blood pressure. Migraines.

And they all started at the same time?

Yes. After I’d turned thirty. It’s hard to say now which came first. I thought I was getting better after closely following the treatments the doctors prescribed me for my migraines, but these were just symptoms, not the disease. (Victor takes a yoga mat, lays it on the floor, places a yellow ball on it, and slowly sits on it where his left femur meets his pelvis. He begins making circular motions. Then he lies down on his back and raises his feet against the wall, lowers them, raises them again.)

When and how did you begin including your kidney condition into your art?

When I got stuck with dialysis, aware of how easy it is to become a prisoner of this disease and how chilling the statistics on kidney diseases is: one in ten adults suffers from some form of chronic kidney disease. Dialysis is right around the corner for many of these people. I thought I could do something useful for them. I returned to making drawings – or, rather, woodcuts, and then linocuts. I made something similar to a poster, posters representing kidneys in various conditions together with provocative captions with the occasional dark humor, like: “Live kidneys for sale,” “Looking for kidney,” “Kidney to give,” “Human kidney. Cheap,” “Kidneys in season,” and maybe I’ll have a version with “Kidneys en gros and en detail,” “Kidney maker wanted.” The hope with these posters is, best case scenario, that a passer-by might become more aware of their condition, might start preventive treatment and, why not, might avoid needing to go on dialysis.

I know you’re working on a documentary self-portrait that includes other people who have to go through dialysis. Can you tell us a bit about the script?

In Dializa mon amour you have three stories from very different people in terms of personality, class, living conditions, and facing different kidney diseases. One of them does his dialysis in Iași and the other two in Chișinău. It’s a journey through the individual stories of these three people that will offer the viewer, and me as well, a starting point in understanding what such a life means. I’m interested in these people as individuals and less in systemic issues, like the available technology or the skillset of doctors.

When do you think it will be done?

I hope it will be done in 2021. It will be the result of three years of research and filming.

How often do you undergo dialysis?

Three times a week.

When you go do you think you’re going “on your shift,” or “to work”? Self-irony aside, do you view dialysis as labor?

You could see it that way. I have my own little locker there, my change of clothes – my work uniform. I can’t go wearing what I want. There’s a quite strict order and procedure. Dialysis involves continuous work on the self. Otherwise you simply can’t physically and mentally bear the blood-cleaning process. It involves a strict routine of preparations and exercises. You need to be constantly paying attention to how your body behaves. Any symptom has to be reported to the doctors. You come to start listening to your body. Some patients who are in better shape read, watch movies or series while hooked up to the devices. Others sit there stiff for four hours looking out into space.

Why linocuts?

I needed something that could be relatively easily reproduced though not necessarily in a very great number of copies. You can technically achieve this with linocuts.

You also made some linocuts about the extradition of Turkish teachers by the Republic of Moldova’s government back to Erdogan’s Turkey. It was, as far as I know, the only artistic response to the events. Could you give us more details on that?

There were two negatives for two sheets of paper. They were put up in various public spaces in Chișinău, especially around the presidency. They showed a masked police officer, like the ones who arrested the Turkish teachers. It was like a pseudo film poster. It advertised a movie that didn’t exist. An image to reflect the situation. The film was called Dictatorii. The premiere date coincided with Erdogan’s visit. The production company was called Orizont Production, like the high school the professors had worked at.

Like in W.J.T. Mitchell’s texts from What Do Pictures Want? Then the police caught you.

Yes, as we were putting up the posters. They didn’t fine us, nor did they arrest us. We just had to take down the poster we were putting up when they caught us.

In how far was this action part of #occupyguguta or #protestpermanent?

The initiative was mine alone, but having connections with the OG activists, I got help from two of them to put up the posters. Of course, there was also that more invisible, intellectual support akin to camaraderie. Same with our actions to save the Gaudeamus cinema. But we didn’t manage to prevent its partial demolition.

You were also one of the people behind Aleea clasicelor. Could you tell us more about that action-work?

We had two things in mind. One – the cultural patriarchy in Moldova, symbolically expressed in the lack of women’s busts on the Alley of Classics in the Public Garden in central Chișinău. We only have male classics, in case you didn’t know. There is currently no female classic there. Two – the impact that writers have on the public space and popular culture in the Republic of Moldova.

We decided to build a cardboard pedestal to resemble the other pedestals that exist – and continue to be installed on a yearly basis – on the Alley of Classics. Behind it we needed to build a stable structure so that our female friends and fellow artists could climb inside, heads sticking out at the top, and stand there motionless, representing potential female writers, scholars, doctors, artists, etc. from our country, which we thought could serve as models for future monuments. Each time one of our colleagues got in we changed the name on the pedestal. The work was conceived together with Ana Godzina, Vitalie Sprânceană, and Lilia Nenescu, but there were also other people involved in finding female models. The money came from crowdfunding initiatives.

After the tent in front of the Guguță café was removed by the police, you, together with other members, installed structures that resembled skeletons of tents. In how far was that an artistic action?

These fragile structures were there to raise questions, stimulate the imagination, and add political dimensions to the public space they were installed in. They symbolized our presence next to the café, a presence of permanently protesting protesters, undaunted and unafraid. The protesters’ tent had been removed by dozens of special forces officers, and even before that the protesters had been frightened with various chemicals. What they were we still don’t know. Our presence-without-presence in the park helped keep the flame of protest burning. This process was continued for example by people photographing these structures and then sharing them on social media. Together with other actions, this contributed to saving the Guguță café in the hopes that one day the building will become a public space again, and perhaps even a space for culture and contemporary art.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Teodor Ajder

Teodor Ajder was born in Chișinău. He studied psychology at Babeș-Bolyai, Cluj-Napoca, and got his master's degree in education sciences and his doctorate in media, information and environmental sc...

Comments are closed here.