I must confess from the very start that Gili Mocanu’s painting has always exerted a constant fascination over me, without being able to fully explain why this happens and how I can get to the source of the “matter”. The truth is that I still haven’t unraveled all the threads of his artistic approach, even now, even after spending a long time analyzing it and “attaching” several theories of contemporary visuality that open up multiple interpretations, but which may as well unravel in a second, requiring rather a penetrating glance and a careful eye. Because there is something in Gili’s painting that always slips through our fingers and that “circumvents” even the most skillful hermeneutical tools, as if to show us once and again that the autonomy of painting and its living, unrestrained body always wins.

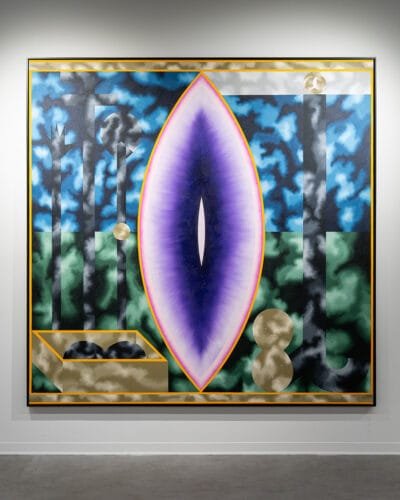

This impression, of a living creature for whom the exhibition space’s “aquarium” is overflowing, overwhelms me even now, after visiting the mini-retrospective “Hill with Skull”, curated by Mihnea Mircan, a long-standing dialog partner of the artist, an exhibition orchestrated by the Ars Monitor Gallery in Bucharest, directed by Silviu Pădurariu and Mia Munteanu, and brought to Timisoara in the ISHO Pavilion. The paintings now on display trace an arc across time and reveal a Gili made up of several artists, all striving to conquer, piece by piece, a new pictorial territory. From the formative matrix of a textually defined visual field, Consonance and Vowel, 2006, to the archetypal paintings of the mid-2000s, to more recent creations such as Revera, 2020-2024, all the paintings now on display define a path along which Gili has nonchalantly ventured, without the fears of the conqueror for whom victory means ego stability. Gili plunges into the abyss of creation without a safety net and without festive expectations, searching not only for the absolute creator, but also for that lost Hermes, who was the foundation of the first creations of humanity and who connects the earth and transcendence, urging silence and arresting the noise of everyday life.

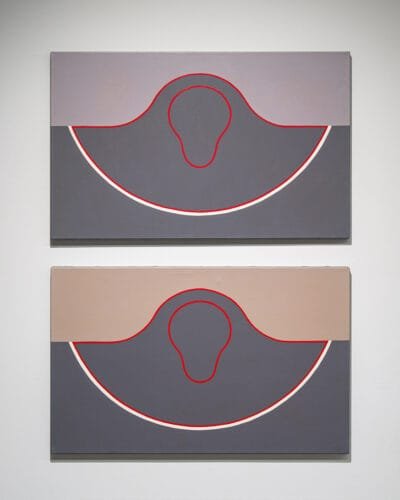

A friend confessed to me while visiting the exhibition “Hill with Skull” that she found the works so vivid and telling, that she no longer felt the need to read any curatorial text. However, Gili Mocanu’s art has also generated some of the most interesting and savory critical texts over the years. And the fact that theorists can’t stop trying to decipher what some have called “magical realism of a minimalist nature” (Oana Tănase) or “mirroring the extra-mind” (Liviana Dan) is a sign that Gili’s painting is more about us than about him, that the relationship that is established between us and ourselves, not just between us and the painting, is essential. If we look at the two paintings that face each other in the exhibition, Revera I and Revera II, we see that they define a space like a magnetic field, where once you enter, you can never leave the same way. The two works, double, symmetrical and “true” to the very marrow of their pictorial bones, pierce the universe of the visual and open a slit to the infinite, completely purged. We find ourselves gazing at one or the other, like a propeller, until our gaze detaches, takes off and distances itself, and we find ourselves gazing at ourselves.

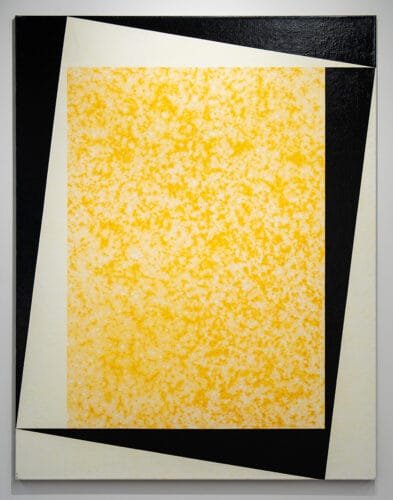

The manner in which Gili Mocanu integrates the double is not always identical. Sometimes the double becomes a doubling of the artistic act and the visual motif – see the “twin” paintings, as in the case described above. Other times that double “frames” an image, as in the untitled 2010 painting of a storm at sea, an image within an image, the painting of a black and white image, dreamed or recollected, not “represented”. Another way of doubling but also modifying an image is the last painting in the exhibition, where the death of painting becomes its rebirth, by calling on a solar Malevich this time, who no longer resorts to a black square to seal the fate of art, but to a vibrant yellow rectangle, which opens access to a painting that will never, in fact, die. In the case of the “twins”, I think that the artistic demonstration goes through several stages. On the one hand, if we reread in Freudian terms the idea of the double, this inevitably pushes us to evoke that primary mental stage, the subconscious, in which information is stifled and blocked, the image can be easily distorted, and the eternal question What is real/original and what is constructed/copied inevitably circles around us. Then, the meta-image that contains itself and everything that moves toward it becomes, in W. J. T. Mitchell’s terms, a “vortex” that absorbs the viewer’s consciousness, spitting back an infinity of reflections like a prism scattering the sun’s rays. And the last stage that the doubling of a motif proposes is the symmetry of the mirror that defines two territories on a knife’s edge. This time it is no longer a confrontation between reality and fiction, an insignificant duality in the larger construct of pictorial creation, but an oscillation between the creator and the viewer, in which the two change roles and perspectives until an uncontrollable vertigo in which each of them (de)doubles itself infinitely.

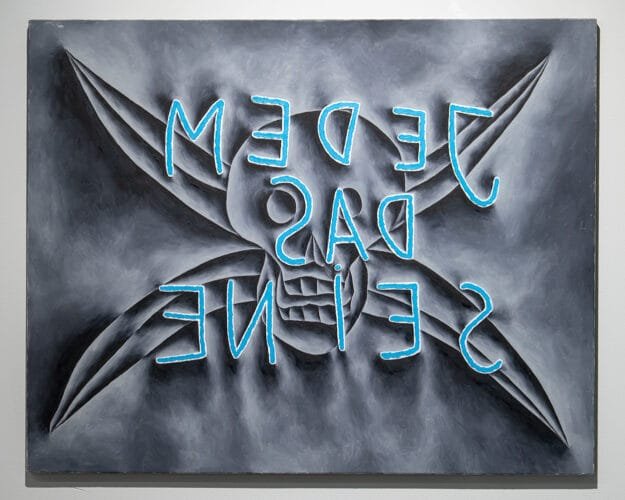

Mihnea Mircan talks in his curatorial text about the relationship between figure and background through the lens of a diagrammatic simultaneity and about another important axis of the exhibition, the visualization of the text, thus transposed into a multilayered motif. The role of text in Gili’s painting sustains a temporary alliance of words in a visible chaining, present as a near monolith, claiming the family of words and concepts from which few are extracted – those capable of sustaining a mirrored “frontispiece”. The text doesn’t seem written, but rather dug, corroded in time, it doesn’t have fluidity, but the determination with which the left hand takes control and tries to trace another course, unpredictable and lacking mastery. The mirroring of the text has perhaps its most powerful impact in JDS, 2011, where “Jedem das Seine” (to each his own), the iron inscription on the gate of the Buchenwald concentration camp, is seen from the perspective of the executioner, the one to whom this message is not really addressed; the one who does not “deserve” to suffer, to die or to be “on the other side”. Once again, the viewer is forced to look at himself, to catch himself on the outside of the twisted rope, wondering how it is possible to circumvent this iron fence and pierce obliquely through a history of winners and losers.

I believe that no other recent exhibition has so cleverly turned a mirror on ourselves, but not in order to look into the depths of our being, as we are perhaps too often and too insistently asked to do, but to remind us that seeing and interpreting are by no means separate, but, as Mieke Bal had already announced, the act of looking is knowledge.

POSTED BY

Diana Marincu

Diana Marincu is a curator and art critic, member of AICA and IKT, Artistic Director of Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara. Her recent exhibitions include: At the edge of the world (co-curator: C...

Comments are closed here.