Michele Bressan, Lea Rasovszky, and Larisa Sitar exhibited together for the first time in 2011, in a self-organized initiative that attempted to break certain norms imposed during their art studies. That is when they presented the exhibition Voiaj in the space that would soon become known to the public as Anexa MNAC.[1] Next came the exhibition Pasaj, also at Anexa, and then, in 2015, followed their participation in the Venice Biennale,[2] both curated by Diana Marincu.

Beyond the initial context that brought them together,[3] the three share a certain way of constructing personal narratives at the intersection with the world. Self-examination, subtle self-referentiality, the need of reflecting on one’s own past in search of truths breeding fascinating fictions, the ability to use visual media to convey poetic feelings hard to put into words, all of these are found, in different forms, in the works of all three artists.

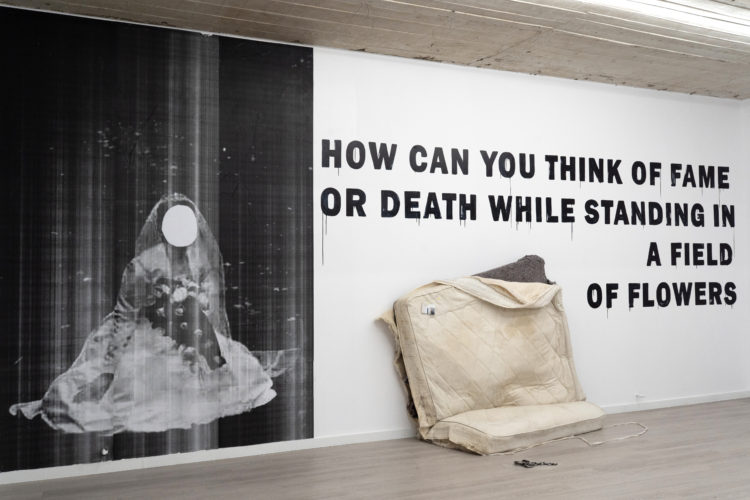

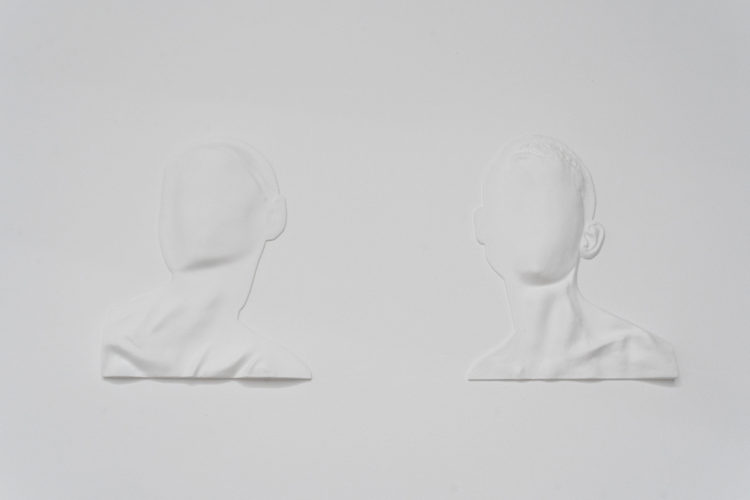

Even though the term bruiaj[4] (translated in the exhibition as disturbance) sets up a clear network of associations within the exhibition, connecting tensions or instituting sudden breaks throughout, there seems to be a second dominant discourse crystalized around the notion of absence. This latter notion appears under various guises and layers of depth: from physical, immediately perceptible absences, like the bas-reliefs without facial features (Larisa Sitar, diptych from the series Roboust Boast), the bride with her face cut out and the male character with his face covered (Lea Rasovszky & Michele Bressan, How Can You Think Of Fame Or Death), from lack of human figures in Michele Bressan’s photos (Cinema Patria and Timpuri Noi), the absence generated by censorship, in the case of the pseudo-icons hidden behind red velvet curtains (Lea Rasovszky, The Impossibility of Counting That Which is Numberless and God As A Boy) or of erased texts (Lea Rasovszky, Ode to My Left Hand), to death as physical disappearance (Michele Bressan, Like in One of my Dreams #0 and Like in One of My Dreams #2), and finally to the absence that gives a sophisticated touch to apparently easily accessible discourses, creating paradoxes in the mind of the viewer, such as the absence of ability becoming a supreme skill (Lea Rasovszky, Ode to My Left Hand), or the absence of materiality producing ghostly sculptures (Michele Bressan, Overhead Projections).

The tight, long-term collaboration between artists and curator and the flexibility of the curatorial approach, allowing for spontaneous interventions, have resulted in collaborative works and rich dialogues from a conceptual and visual standpoint. The most relevant example here is Lea Rasovszky’s in situ intervention How Can You Think of Fame or Death. Her original work involved appropriating an image from a website for second-hand wedding dresses, where the person selling the dress crops out their face to preserve their anonymity. Lea takes this photo of the faceless bride out of context and turns it into a large wallpaper print, an enigmatic apparition accompanied by the text How can you think of fame or death while standing in a field of flowers, which can spark numerous interpretations. Spontaneously, while setting up the exhibition, Michele Bressan adds two elements to this intervention: a filthy old mattress found on the artist’s daily route and a found footage still: a photo of a real estate agent with his face blacked out found in an ad for an apartment who becomes the male version of the faceless bride. This represents a dialogue between two distinct realities that will never meet in real life but which become possible and plausible in the exhibition context. The displacement and association give rise to a parallel narrative, augmented by a symbolic object – a fragment of a chain – added by Larisa Sitar. This last element is reminiscent of violence, contains a kind of latent aggression, as do the other elements of the installation.

Beyond these interactions, each artist also brings in personal projects or series with newly added elements. Larisa Sitar contributes a very unified series, Roboust Boast, which she began in 2019 during her residency at WIELS in Brussels. Her bas-reliefs, whose conceptual starting point is how the nostalgia of the past reflects itself in architectural decorations, are now complemented by a small domestic setting, a sample of early ’90s Romanian interior design. This setting consists of a collection of velvet armchairs with period-specific print, the omnipresent glass coffee table with golden inserts, and the marble-print tiles. The artist remodels the spaces in which transition-era children grew up, the time when the interior furniture and materials on offer were expressions of the questionable tastes of manufacturers that did not give serious thought to interior design, just like the stucco designs imitating neo-classical bas-reliefs represent cheap, borderline-kitsch interventions.

The numerous directions that Lea Rasovszky explores, which are exhibited together, namely the drawing with her left hand, the portraits investigating masculine types, and her more recent attempts at transposing them into the medium of ceramics, are so dense in content and visual expressions that they could function as micro-exhibitions on their own.

Lea Rasovszky’s relationship to drawing, the way she uses the medium to create hybrid imagery born out of bizarre connections, is based on fragments of memory or spontaneous perception. The texts accompanying her drawings are sometimes confusing, other times revealing, but always involving the same kind of fully assumed subjectivity. Lea is herself throughout her drawings and texts, but, at the same time, she allows you, the viewer, to be yourself, to use your own powers of imagination, like in a psychoanalysis session. There are no dominant narratives, nothing to restrict one to a pre-given reading.

The Ode to My Left Hand project focuses on the novel directions that can be opened through self-imposed restrictions, creating uncomfortable situations, overcoming challenges with potentially unexpected results. For Lea Rasovszky, this is a way of severing the invisible ties with the habits instilled during her arts education over a long period of time, a way for the artist to forcefully repress that which habit does not allow you to naturally repress, in order to allow the untrained and uncertain hand to surprise you. The series Nightmare at the Drawing Olympics also functions as an incisive critique on how art education kills creativity. Academic drawing and studies of plaster casts become pretexts to deconstruct a classical experience of learning to draw.

Transposing a subject into multiple media of expression is another feature of Lea’s work. One of her characters drawn with her left hand materialized into a sculptural object made from a frame on which hangs the livid-skinned figure made of latex, having abandoned the vitality it showed in the drawing. The painted male portraits are transposed into ceramics in experimental fashion. The busts from the Criers series are animated with various dynamic elements, like the flowing tears of the characters, a constant weeping that leaves a mark on their faces’ pigments. Their framing between dried flowers augments the work’s feeling of sentimentality and nostalgia.

Michele Bressan also returns to an older topic. His work Like in One of my Dreams #0 shows a model of a hearse, related to a model he made in 2014. The narrative however flows in reverse, as the first work in the series shows a later point in time: that of the funeral.

His intervention outside the exhibition space can also be seen as a return to older preoccupations. The sculptural object placed in front of the Art Encounters Foundation’s office is a cross section of a World War II bunker. The intervention is tied to the project RAPI (Romanian Archaeological Photography Index), which was done in collaboration with Bogdan Gîrbovan and consisted in investigating former warzones, digging up objects there, and photographing them.

One way Bruiaj succeeds as an exhibition is by offering a deep problematizing of the concept of memory. If macro-history as a science attempts to recover factual memory, however it might be recorded, for micro-history it is fictional memory that is essential. In constructing a personal or small-group identity, recounting factual evidence is no longer enough. What is also needed are the fictions born out of facts. Most of the works in Bruiaj have this quality, testing the possibility of a fine-tuning between the articulation of intimate states, subjective experience, barely perceptible sensations, without obsessively explaining every artistic gesture. The ideas are allowed to sift freely through the overlapping layers of disturbance. Clarity is here synonymous with coherence rather than with redundant explanation.

The exhibition BRUIAJ, curated by Diana Marincu with artists Michele Bressan, Lea Rasovszky, Larisa Sitar, opened on February 28th 2020 at Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara.

[1] Anexa MNAC was housed between 2011 and 2015 in the building belonging of the National Museum of Contemporary Art on Calea Moșilor. Voiaj, opened in 2011 during the White Night of Galleries, set a precedent and played an important role in transforming the spaces within the building into exhibition spaces.

[2] The exhibition Inventing the Truth. On Fiction and Reality took place at the ICR Gallery in Venice, the collateral space of the Romanian Pavilion. The artists exhibiting together with Michele Bressan, Lea Rasovszky, and Larisa Sitar were Carmen Dobre-Hametner, Alex Mirutziu, and Ștefan Sava.

[3] The three studied together at the photo-video department of the Bucharest University of Arts.

[4] Diana Marincu explains the choice of the name in the curatorial text: “This disturbance forces the path of visual experience to multiple detours, diversions and surprises stemming from themes such as the aesthetics of the private space, the everyday eeriness, funeral rites, military arsenal, ruin, and disappearance.”

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Maria Orosan-Telea

Maria Orosan-Telea has a background in art history and theory at the Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca. She arrived in Timișoara in 2009, to continue her doctoral studies at the Faculty of Arts...

Comments are closed here.