After the revolutions of ’89 and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the West has become rather engrossed with the events from East Central Europe. During the last decade of the twentieth century, various exhibitions, presenting Eastern European artists, were organized in the West, exploring the particularities of this area, the political changes and the role of the artist in a period of transition (Europa, Europa 1994, Der Riss im Raum 1994-1995, Beyond Belief 1995, After The Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Comunist Europe 1999 etc.). The gesture of organizing these exhibitions encompasses the curiosity of the West and its desire to delve deeper into the Eastern European region, believing it to be more of an exotic and primitive space, where, as Slavoj Žižek claims “in Eastern Europe the West looks for its own lost origins, for the authentic experience of ‘democratic invention’”.[1] However this interest is not unidirectional, Eastern Europeans have always been lured by the West, wishing to belonged there. In her essay, Romanian Democracy and Its Discontents, written for the catalogue of the Beyond Belief 1995 exhibition, Roxana Marcoci notices the peculiar relationship between the two Europes, which seems to be “a seductive exchange of mirroring gazes, a narcissistic mode of subjectivity wherein each perceives the other as desirable and worthy of love”.[2]

This dissonance and mutual attraction were fueled over time and they’re vaguely discernible even today. 30 years after the Revolution, the East still views the West as a “promised land”, and the two exhibitions that took place in Timișoara, Europa Wonderland (curator – Olivia Nițiș) and Body Space: Territories and Citizenship (curators – Olivia Nițiș and Dana Sarmeș), attempt to dissolve this illusion. One of the exhibited artworks intentionally provides a different image of Europe. MIRAGE. Side effect of a fabulous promise by Cătălin Burcea, reveals the abstract topography of the continent on the backdrop of disquieting and alien sounds, alluding to the fabrications that occur in relation to Europe out of ignorance and need for illusions.

The two simultaneous exhibitions, which are intertwined, supporting each other, try to simulate a Wonderland of seeking an identity and personal and social frustrations. A Wonderland, not like that of Alice which fascinates precisely by the improbability of its existence, but one that is much closer and uncomfortably real. Thus, the exhibitions represent a map of Europe on which the twenty invited artists marked their own worries and revolts.

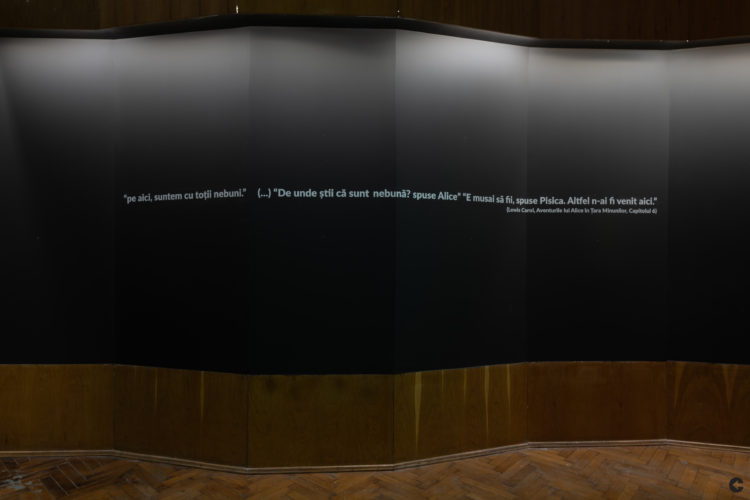

Similar to Alice in Wonderland, where an impossible world is revealed, questioning the concept of limit and moral code when everything is allowed, the exhibition presents Europe as a world of every possible and inevitable trouble, disputing the existence of a social contract of each individual and the limits of personal freedom.

While Body Space: Territories and Citizenship discloses the individual experiences and frustrations of artists related to the outside world and its limits, Europa Wonderland offers the economic, political and social context where artists are in a permanent oscillation. The two exhibitions should be viewed incorporating the same discourse that challenges the utopic dimension of Europe, slightly disintegrating the image of a “promised land” attributed to this area and debating the need of a European identity and what that would entail.

Starting from his own pilgrimages through Europe, Ciprian Homorodean reflects, through his work LIMBO 20/20, on the European ideal of supranationalism, which seems to be overshadowed by the growing nationalism and the spread of stereotypes in recent years. The artwork consists of 27 boom barriers, distributed in a circle and raised at different heights, while Chubby Checker’s Limbo Rock plays in the background. Despite the free circulation between countries (an aspect that drastically changed because of the pandemic), crossing borders is seen as a limbo dance, in which the difficulty level increases and the risk of disqualification is much bigger due to cultural differences and growing nationalism. The artist explores the concept of freedom and limitation, which, as in dancing, come to determine each other.

Beyond the hopeful aspects and the normal life of migrants, which Sanda Sterle pursues through her work Angered@home, the phenomenon of migration also encompasses less pleasant dimensions, such as discrimination or even closing borders in some European countries. Sorin Oncu, a great Romanian artist of Serbian origin, who passed away in 2016 and to whom the exhibition pays homage on this occasion, disputes the hostile attitude towards foreigners. The work A motto of disappointment LIBERTÉ ÉGALITÉ FRATERNITÉ consists of three large, black canvases, which allegorically imply the image of death or mourning, and on which are inscribed the three values of the French Revolution ideal, being, in fact, written in Arabic characters. An ideal with global implications that does not seem to work in relation to the Arab world. The media, the policies of rejecting the waves of refugees and the fear of the ISIS terrorist organization have led to the mass conviction that Muslims and Arabs are terrorists. But how fair is it to operate with generalizations and stereotypes? With his usual simplicity, Oncu tries to deconstruct false perceptions in relation to the Arab world and to criticize the ignorance and the hypocrisy of the West.

However, the exhibition is not strictly limited to the geographical outline of the EU, but presents multiple external perspectives. For Ardan Özmenoğlu, a Turkish artist, Europe means absolute freedom and gender equality. The artist vehemently criticizes acts of violence against women as well as the position of the Turkish state, which does nothing to protect them, but instead plans to leave the Istanbul Convention – a convention that prevents and combats domestic violence. The work Red represents the portraits of the victims, screen-printed on post-it notes as a symbol of memory in order to bring to light the deplorable situation women are facing in Turkey. The artwork resembles an unsettling website – a digital memorial to women, that records the annual number of murders and the circumstances in which they occurred, while criticizing the superficial approach to this topic as a mere statistic.

Capitalism, perceived after ’89 in the Eastern European region as a lifeline and proximity to the West, is viewed skeptically by contemporary society because it emphasizes human superficiality. Andrea Cioară, a young artist from Iași, created a curtain of labels from clothes, trying to understand why people value objects so much, to the point of replacing human affection with them. Curtain represents a commentary on the consumerist society and the superficiality of our choices. The attachment to objects and labels is only on an emotional level, deceiving us with their usefulness, so that the desires do not reflect our needs anymore, or even, as the artist says, “desires exceed our possibilities”. Although each piece of clothing has its own history inscribed on the label, people attribute their own stories to it, forgetting about the production process, the country of origin, the cheap labor involved and thus unconsciously supporting consumerism, through a complex process of alienation. Cosmin Haiaș, through his work Made in China, also makes critical comments on consumerist society. The work, which visually coincides with the title, offers a feeling of luxury and grandeur, which are actually cheap, trying to imitate authenticity. Haiaș criticizes the hypocrisy of the western society that strongly wants to remove what is foreign, self-deceiving itself through a “Certificate in Europe” pasted on imported products. Why do we need this Western affiliation even for the products we use?

After a long process of democratization and closeness to the West, the trauma of the Ceaușescu regime still does not seem to fade away, and the remnants of communism can still be found in people, in houses, in ruins. In the post-socialist/industrial context of the country, Sarah Muscalu explores the concept of ruinophilia (introduced by Svetlana Boym). Ruinophilia is the fascination with ruins, which is different from nostalgia, because it does not imply a melancholy and longing for the past or what the ruins represented before they were ruins, but rather experiences the irreversibility of time and the present state of ruins. Romania’s recent history resembles a “palimpsest of architectural and identity reconstruction” on the foundation of socialist industrialization. The artist’s work, Under Construction (an installation consisting of an oil painting of a ruined building, over which a plexiglass covered with a layer of plaster was placed) questions the current condition of the relics of the former regime. By sandblasting the plaster layer, its remains represent a replica of the ruin in the painting, and the very gesture of gnawing the plaster reveals the need for a collective effort to overcome the post-socialist condition of the country.

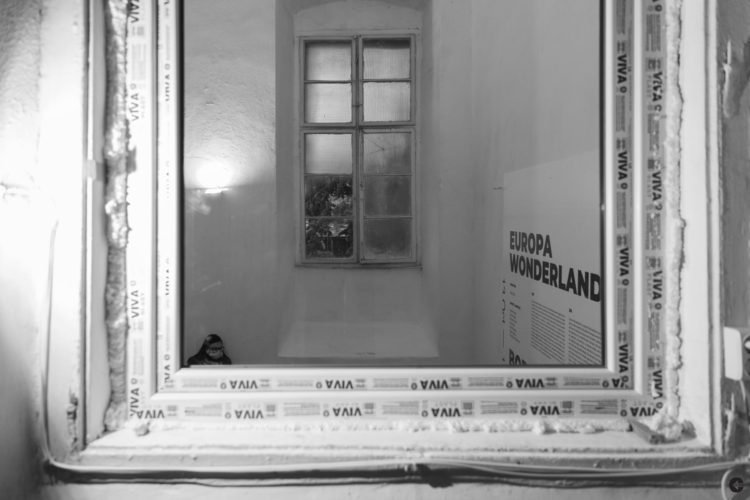

The exhibitions Europa Wonderland and Body Space: Territories and Citizenship took place in a significant space in Timișoara – the former Garrison Command building, which is a valuable heritage building. Due to the current condition of an institution in transition, to be renovated for the opening of the Museum of the Revolution, the Garrison represents a symbolic space for the theme of identity explored in the exhibitions. Claudiu Cobilanschi protruded this space with some early “renovations”, he installed a double-glazing window in an already existing frame. Window to the Future is an ironic work that criticizes the superficial postmodern renovations of heritage buildings. Intentionally installed with the handle on the outside, so that it cannot be opened, the window becomes useless and ridiculous, representing the absurdity of the situation in which renovated heritage buildings end up losing their architectural value, an absurdity that, unfortunately, has become commonplace in Romania.

The event is an exhaustive and complex research, and although it may seem like a victimization of the individual in an illusory world, the exhibitions’ manifesto advocates strengthening the social contract and criticizes the open ignorance of people who detach themselves from issues that do not concern them personally. In the current Romanian context, a visionary exhibition on Europe and on its own condition was more than necessary, in order to disperse hollow illusions and to pragmatically reset freedoms and limits.

Both exhibitions took place between 13.10-13.11.2020 at the Garrison Command, Timișoara.

EUROPA WONDERLAND

Curator: Olivia Nițiș

Artiști: Cătălin Burcea, Cosmin Haiaș, Delia Popa, Matei Bejenaru, Valeriu Șchiau, Decebal Scriba, Zoița (Delia Călinescu).

BODY SPACE: Citizenship and Territories

Curators: Olivia Nițiș and Dana Sarmeș

Artiști: Ana Hoffner ex-Prvulovic (AUT), Andreea Cioară (RO), Ardan Özmenoğlu (TU), Ciprian Homorodean (RO), Claudiu Cobilanschi (RO), Elana Katz (DE/USA), Mălina Moncea (RO), Renée Renard (RO), Sandra Sterle (HR), Sarah Daria Muscalu (RO), Sorin Oncu (RO), Veronique Sapin (FR), Xenophon Sachinis (GR).

[1] Slavoj Žižek, “Eastern Europe’s Republics of Gilead”, in New Left Review I/183, September-October 1990

[2] Roxana Marcoci, “Romanian Democracy and Its Discontents” in Laura J. Hoptman, László Beke (ed.) Beyond Belief: Contemporary Art from East Central Europe, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1995

POSTED BY

Marina Paladi

Marina Paladi is from The Republic of Moldova and is a master's student in Heritage, Restoration and Curation Department at the Faculty of Arts and Design, West University of Timișoara. She is intere...

Comments are closed here.