The year 2019 was marked by the early departures of some Romanian visual artists who were at their peak and who could’ve continued creating for a long time if the thread of life hadn’t been so brutally interrupted. Such moments short-circuit the linearity of our daily lives, realizing how fragile life actually is. We selfishly consider tomorrow as already belonging to us and that we still have time. We believe that time is a friend we usually negotiate with and to whom we give too much confidence, considering that our inner rhythm is automatically linked to its natural flow. Time has never been our friend; perhaps time is our biggest opponent, not to call it an enemy. Time is betraying us.

Beyond the loss of a human being and the gap that his absence leaves, when I see a creator die I think of all the works they did not have time to do and, at the same time, of the ones they already made which acquire a completely different dimension, knowing that there will never be a person who thinks exactly the same way, that feels the same and conceives the matter in the same manner. When a person dies, a world ends. There is a sense of helplessness and of resignation all at once, we cannot stop life. Death is part of life. And death makes us most ruthlessly aware of the substance of life. There is a moment of lucidity that almost gives me a sense of asphyxiation, I can’t breathe, that I don’t know how to breathe if I free my mind from what I know in order to become conscious of the unknown. Inevitably, the question arises: would it happen to me? I think every one of us even asked themselves this question for a fraction of a second in the face of sudden death. The answer essentially does not matter because we will not find it anyway. What matters, I think, is rather the answer to the question: What do we leave behind?

The fine art artist creates objects through the specificity of his work. It is an extremely palpable and concrete trace, an undeniable testimony of a consciousness. The object bears the mark and is the result of affirming an existence. However, like the human body, the artistic object does not escape the perishable condition and the relativity of its preservation over time. How long will it last after we are gone? Under what circumstances is it recovered, recalled, archived? Artist Adriana Jebeleanu, at the end of her Blind. Deaf. Mute performance, stated the following: “The artist gingerly flaps their wings, blowing giant tornadoes in the sky. Their mute roar, their blind crying, their deaf heart beat make the artist a special being. Sentenced to death, freedom would be their last word on the scaffold. I’m an artist, nice to meet you. ”

Freedom is indeed the red thread. Not life and death. Or at least that’s what I like to believe. Freedom to feel, to comprehend, to break away, to create, to think, to decide, to be. Freedom to choose whether to leave something behind.

Possible mental interrogations about motivation in the artistic process as a first step to leave something behind: What makes you? What breaks you? What’s your “Achilles heel”? To what extent does it make you to break you? Do you like playing with your limits? Do you really want to face them? To what extent do you think you have something to express and pass on? Why did you want to make art? Why are you still doing this? If not, why did you give up? Are you writing about art? Why do you do it? Do you like to judge, to criticize? Are you looking for meaning in something that makes no sense? Do you think there must be some meaning or that things simply happen? Are you afraid of mediocrity? Does ignorance have nothing innocent and pure within it? Do you like the idea of control? Do you think you can control? Do you want to have your control? Exercises in freedom that can go on and on.

Somewhere at the opposite end, one of the most paradoxical contexts in which an artist’s legacy is capitalized materializes in an art auction event organized by big auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s. I am not referring to art auctions in general, but to this particular case in which invaluable art objects were made by artists who are no longer alive. What they left behind as a result of tumultuous, difficult lives, often lived without thinking of material benefits or the idea of leaving a cultural heritage to mankind. There is a phenomenon that I always dissect mentally because of the contradiction and the paradox of the situation. I allow myself an exercise in freedom in finding an auction full of masterpieces to be fascinating while, at the same time, perceiving it as an incredibly sad phenomenon. It’s an adrenaline rush I feel when involuntarily looking at such an event not because it represents the dream of any artist, but because I am accustomed to cultural acts beings synonymous with financial struggle and a lack of infrastructure, yet here I am, within a context where money is not a problem. But in fact, in the most ironic way, all money becomes problematic. Why? Because everything revolves around financial investment. Prove me wrong. I honestly expect someone to come up with pertinent arguments that prove that this incredibly well-organized show is about capitalizing on universal culture.

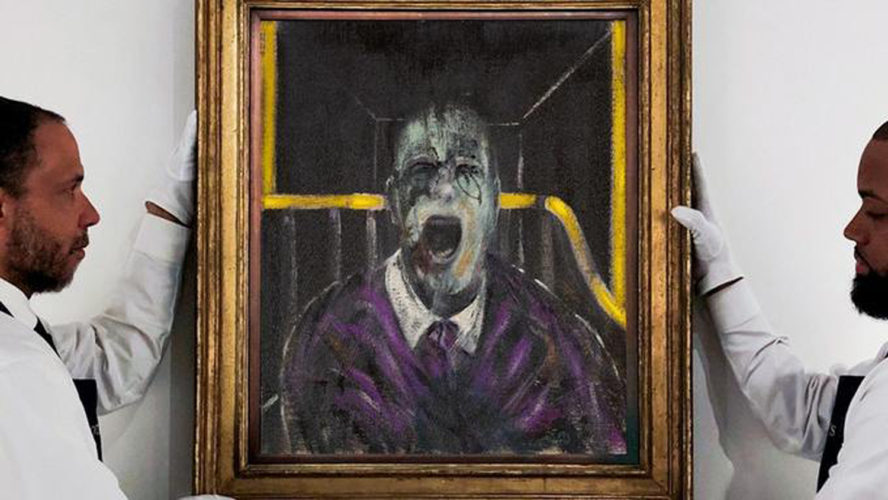

Every time a new piece of art enters the stage to be auctioned, I feel a knot in my stomach because I perceive the object, which I most often recognize immediately, I visualize the artist and their life, most of the time tragic or ,at any rate, extreme, I look at all the office/cocktail context and think of the great absence. The absence of artists and the absence of bidders (they are always on the phone, to keep their identity secret). And, of course, the absence of money, which is naturally scriptural, because there is so much money, so much that I cannot fathom it. What is being traded here? Value? An idea? A status? A projection? An illusion? The object of art bears the artist’s energy, it contains all an immense psychic and emotional load, the interface between them and the world, materialized into an object. Why would you want to give $40 million for a Francis Bacon work? I would not want to keep a Bacon locked up in a vault, precisely because of everything behind his work. It’s his life, and the freedom with which he has assumed his work, I would not want to keep it just for myself.

Bacon’s life should not be made available only to the elite, and his death should not be one of the main factors for which the object of art becomes invaluable. His own life, whose testimony is the work left behind, should be the reason why the object become invaluable. His work, in its universality, to be seen by any person, and what was left behind to be recognized as evidence of the freedom with which he embraced his own existence.

I try not to make any final judgments until I can see for myself that which I want to judge. As for the Sotheby’s auction house, I saw it in 2015 when I was in London for a long period of time, after long self-interrogations and uncertainties if I was going to be allowed to actually get in. As I discovered that the auctioned works were displayed in open public exhibitions, I decided to go see Sotheby’s for myself, to absorb the energy of the place. I did an exercise in freedom by deciding that regardless of the dress code, I would not wear the most elegant clothes in the wardrobe, nor will I try to appear as something I am not – but I will assume my identity by naturally going in just like any other ordinary person on the street. I was not very surprised to find that there were very few visitors, with the exhibitions mostly being attended by men in suits, who were also viewing the price tags, so possible collectors. I spent a couple of hours in Sotheby’s because they had lots of works, from both the modern and the contemporary era: Francis Bacon, Edvard Munch, Damien Hirst, Banksy, Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter. I witnessed, in passing, the hanging of a piece of the Campbell’s Soup Cans series by Warhol, which was being handled with white gloves, obviously. The contemporary auction featured a series of screen printings of Marilyn Monroe, and in an adjacent room there was a collection of personal belongings of the Beatles, which were integrated into a thematic auction. In other words, I was greeted by a royalty of famous works, within a very precious setting. These were valuable in themselves, and that was enough, but the frame of the exhibition would place them in a mercantile show, from my perspective.

The feeling I left the auction was a liberating one, because although I felt curious or very subtly condescending looks sent my way, it did not affect me in any way, on the contrary, the live experience of the space confirmed to me that the luxury in which art is promoted and with which it is associated has nothing in common with its substance – it describes a social context, nothing more. By visiting Sotheby’s while wearing jeans and sneakers, I have been forcing myself to untie stereotypes and prejudices and to perceive a phenomenon created around the artwork without judging the object of art according to the phenomenon.

Returning to the artistic product and the idea of cultural heritage, what we leave behind is a very personal decision, whether it’s conscious or not, which is the testimony of our existence within the known coordinates of life. Whether we leave sooner or later, what remains is our collision with time and what results from it. Ioana Nemeş, in the Times Colliding exhibition, inserted the text: “Freedom as another form of tyranny, like another wonderful cage.” Freedom can become a cage, but it’s the only thing that belongs entirely to us. What do we trade in this life? Everyone decides for themselves in a free and authentic way. What we leave behind us defines and marks a reminder of a particular vision. Whether we look at universal art or focus on local contemporary art, the material footprints left by artists come to celebrate a way of life, a way to perceive the world and they remain like portals – ways of accessing a consciousness which continues to live metaphorically through them.

POSTED BY

Ada Muntean

Ada is a Graduate of University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca and has a PhD in Visual Arts (2019), conceiving a research thesis entitled "The Human Body as Image and Instrument in Contemporary Art....

Comments are closed here.