(myth and silicon)

Nowadays, Cluj is considered in Budapest as a cool tourist destination and a cultural phenomenon. European travellers: art from Cluj today, an exhibition at the Hungarian capital’s Kunsthalle (Műcsarnok) back in 2012 endeavoured to create the myth of Cluj here, and also contributed to this image of the Romanian city. I do not intend to discuss the exhibition here in detail, but I find it necessary to note that many players of the Romanian city’s scene considered that exhibition as one that showed a distorted image, and eyebrows were also raised about the Kunsthalle as the venue for the show. Of course, considering today’s state of cultural institutions in Hungary, even the way the Kunsthalle was in 2012 seems to be like a dream now. Cluj is cool, indeed. And sometimes surreal. For example, real estate prices, which are said to have soared when Eastern Europe’s Silicon Valley emerged here (the IT sector currently accounts for 6% of Romania’s GDP, and it is expected to grow to around 10%), and IT companies began to pay reasonable salaries to their employees. In the same context, the city has performed a leap. As the people I met in the Insomnia Café put it: just imagine a city the fourth of Budapest, with the same amount of money for development. Okay, I imagine it. Even if the money is not the same, the dynamics may be the same. What really strikes the eye is the number of small art projects, artist run spaces and initiatives that somehow stay alive. Romania has a national cultural fund called AFCN – for a long time there was no such institution there, and they envied us for ours, the NKA –, which allocates funds independently of politics. Plus, sometimes the municipality provides funds too. Importantly, Romania is a country that has more than just one city as a centre. Although making the short list, Cluj was not selected as the European Capital of Culture in 2021 (it will be Novi Sad, Serbia and Timisoara, Romania), but it is probably even better this was because it is better to leave things develop naturally, in their own way, and it is also better if culture is not used by political powers for representation. The alternative cultural scene here seems only to need venues for the projects and money they can apply for.

The Fabrica de Pensule / Paintbrush Factory is above the red line. There is no threat whatsoever to its existence – although several artists now need to pack up and leave because the building’s owner will renovate the two top floors and then rent them out as office spaces. Art will stay in the building, but on the lower floors. The Paintbrush Factory has become a legend, however, I was not so interested in its genesis, nor in the schism that took place last year, but in the various artistic lines of practice that are present there. Although his work was exhibited in the exhibition at Budapest’s Kunsthalle mentioned above, Cristian Rusu says there is no such thing as a Cluj School of painting, at least not in the sense there is a Leipzig School. When I went to the Paintbrush factory to meet him, he was busy moving his stuff from one floor to the one below to free space of the offices. As many of the artists observed, although the Factory’s infrastructure is fine, and the raggedness of its walls gives it a cool retro feeling, it is not likely that its spaces can be rented out at the current market prices. As Cristian Rusu was just moving his stuff, it was easy for him get his works off the shelves to show me. He asked me about the situation in Budapest, and when I tried to use the name of the Ministry of Human Resources to illustrate the change of the situation after 2010, our discussion soon turned in the direction of the main subject he explores in his work, the critique of modernist totalitarian visions.

(give me back my mountains)

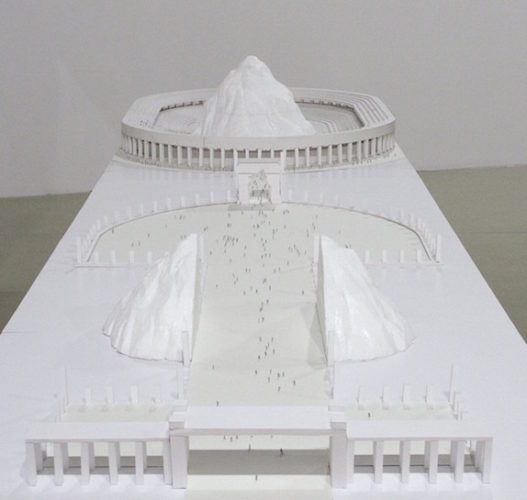

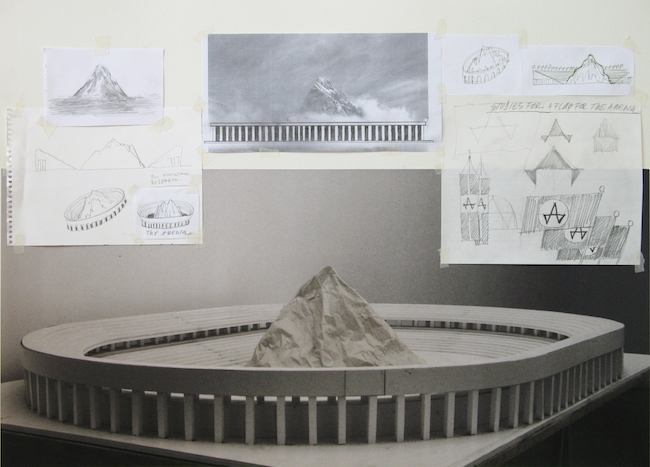

He shows me the draft of a scale model (The Alpine Project, 2014), a kind of city design – and an emblematic work in his oeuvre. The central element of the imaginary city and system is a mountain. The mountain, the peaked shape is the symbol of power, stability and aspiration to the sky, a totalitarian symbol, something that will be there for eternity. The mountain is an artificial object in this city, and the road leads to the grand avenue through the mountain split in two: a man-made gorge. The composition is imbued with irony, but as if it had been designed by Speer, with pillars on both sides, the avenue runs into a stadium. In the centre of the oval arena, there is another mountain – to be extolled, to be cheered. The mountain, this formation, the purpose and meaning of construction, of city architecture is there to be admired. As though it had come here from one of Caspar-David Friedrich’s canvases, the mountain is mysterious and raw, as is creation.

Parts of this work were exhibited in Budapest in the show Pensive Pictures, Goodbye (2014) at Higgs Field, a venue that is no longer there. The works in Rusu’s project are perfectly relevant commentaries on the current situation in Hungary too. While they are site-specific, his anti-monument scale models are universal at the same time. One of them came to be built in reality: a perfect pedestal with a naturalistically made bronze horse getting off it. The equestrian statue remains an eternal topos, even if today’s heroes rarely ride horses, but this time, even the horse has had enough, the artist explains as we are looking at other monument models. One of them is really breath-taking: it is called Wagon of Salt (2017), and there is hardly any chance for it to be carried out in reality. It is about a secret deal between state socialist Romania and Yugoslavia, which pursued an alternative path in building the socialist state. In the deal, Romania offered a railcar of salt for each Romanian citizen captured while trying to escape to the West through Yugoslavia. Timisoara and Novi Sad, the two European Capitals of Culture in 2021, would have been the locations for a railcar stranded on a short pair of rails in either city, with salt left to the weather, melting away slowly with time.

(plans)

In fact, the scale model, or the plan, has become a self-standing genre, especially in this region, where larger works are made rarely, due to the absence of institutional funding and other resources. An annual project by the AiciAcolo Pop Up Gallery (Flaviu Rogojan, Edith Lázár and Thea Lazăr), just one floor below Rusu’s in the Paintbrush Factory, seems to comment on this problem. Every year, they ask artists for Xerox copies of their works and then compile a book of the copies – a print of something that is complete, and a plan of something else at the same time. And this is what makes all that AiciAcolo does so agreeable: it is based on the intermediary, on illocality, the absence of fixed points of orientation, and on the uncertainty of a plan finally being carried out in reality.

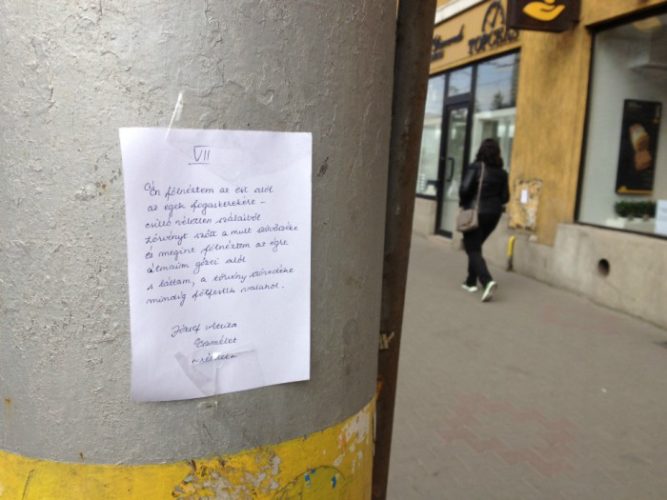

This, despite the fact that Cluj is not short of spaces – and even the public space has not been fully monopolized by business or political power. Street marking is far from being a safe kind of artistic activity in Hungary, this is also why I was amazed to see, in the morning of April 12th, handwritten copies of quotes from Hungarian poet Attila József’s poems glued on the walls and utility poles along Bulevardul 21 Decembrie. I saw the lines of the poem Eszmélet (Consciousness). Lines of that poem echoed in my head for days after that, about “the fabric of the law”… “always bursting apart somewhere”, and “what is, crumbles into fragments” (Translated by Michael Beevor).

(institutional trans)

The transitory state has become permanent – so to say –, for people in Eastern Central Europe. In Cluj there are as many as two tranzits. One is tranzit.ro, part of the network of art institutions sponsored by Erste Bank. The other is older: Tranzit House’s history goes back twenty years. While the two institutions differ in their lines of activities and positions, which may sound surprising considering that the city is not too big, what is common in them is their permanent transition. tranzit.org is now living in the threat of Erste slowly shutting down its exemplary art support programme, but the institution seems to have been embedded enough to keep on going. What exactly it is embedded in is an interesting question: rather than local exhibitions, it is a supranational critical discourse. Even within the transit.org network, tranzit.ro represents a highly progressive line, with a unique character. When I visited the place, there was no event there as the building was being refurbished. I found only a few punk bands working there, moving their sound equipment from the basement after a concert the night before. Nevertheless, I found out that this branch of tranzit.ro (tranzit is active in Bucharest, Iasi / Jászvásár and Sibiu / Nagyszeben too) focused its activities on discussion forums, debates, video screenings and collaborations, presenting critical positions. Not only is this exciting and risky, but also beautiful, as the programmes are held in a space revamped from what once used to be a printing workshop, about three minutes from the city centre, and where, as I found out from Attila Tordai, the head of the local tranzit.ro branch, Miklós Gáspár Tamás also used to work as a typesetter.

The Tranzit House was established in 1997 as a pioneering initiative, and is now preparing to look back on the two decades since its foundation and assess them. It seemed to me that the anniversary is also the occasion to redefine this institution’s role because the cultural context in which it exists is changing fast. The people of the Paintbrush Factory now in their twenties were little kids when the Tranzit House was opened in the building that had once been a synagogue. And now, these young people pursue practices different from those of the late 1990s. Nevertheless, the Tranzit House participates in interesting projects, such as an international initiative for the research of local Jewish community memory. The building itself can also contribute valuable data to the research. The building was once owned by the grandfather of Hungary’s renowned choreographer and stage director Ferenc Novák, and was the site of the first aluminium foundry in the region. It was him who sold the building to the Jewish community in 1921. This is how it became the local tradesmen’s synagogue. It was lunchtime when I got to the House. With fresh vegetables, cheese, ham and bread on the table, all from the local market, I was thrilled to accept my hosts’ lunch invitation. While munching on the delectable food – I listened to my hosts about the story of the House, and the handwritten quotes from Attila József’s poem that I had seen that morning sprang to my mind: “Like a pile of hewn timber, the world lies heaped up on itself” (Translated by Michael Beevor). It was because, as we were having lunch, Péter Novák, a descendant of the building’s first owner was holding a rehearsal of The Marriage of Figaro not far from us, at the Hungarian State Theatre. He directed the opera there in 2015, and won the award for the opera performance of the season in Romania in November that year.

(risk level)

To be honest, what I saw of the official art scene in Cluj was rather poor compared to the alternative. I was happy to find a real crowd attending the opening of the exhibition titled 6+1 at Cluj’s Museum of Fine Arts, the Bánffy Palace. Indeed, it was a real social event, with small talk, a meeting of friends, in many languages. The exhibition was rather academic, as if the works had been selected from a scene totally different from what I considered general and natural in that city. “I don’t like an art that makes the viewer feel uncomfortable while posing no challenge to the artist,” says performer Kata Bodoki-Halmen not much later at the Papillion café. She points it out in relation to the theatre, while she distances herself from the theatre as a genre, and defines what she does as fine art. And to illustrate what she says, she tells me about what she is doing these days. Nocturnal Privacy is a solo performance in the sense that it is for one viewer at a time. The Universal Pleasure Factory presents 12-minute performances for an audience of one at a time, at a venue called ZUG.zone. The show lasts for six hours, this is how long the performers work for the spectators who come one by one. And what happens in the performance is the noises in the dark room, movements, the acoustics of the space, its music and ambience, the action in the space, flashes of images, states and situations that emerge, filled with tension. “We should not reduce ourselves to the position of merely executing things dictated by others,” says Kata Bodoki-Halmen, who cannot be accused of not exposing herself to the vicissitudes of life. She does not spend on accommodation, has squatted across Europe, and spent no money on food when she was living in Barcelona. And this is what sums up Cluj’s art scene for me: the readiness to take risks, to reject conformism.

(horses’ Easter)

Horses’ Easter is something like “when pigs fly”, “when hell freezes over”, or “twelfth of Never”, to say that something is so far in the future that in fact, it will never happen, or the conditions for it to happen will never be there. However, horses’ Easter does exist, as the idiom is said to refer to the rare calendar phenomenon when Catholic and Orthodox Easters coincide. This is when horses can rest in the village. Otherwise, at Easter Romanians borrow Hungarians’ horses or the other way round, as they celebrate Easter at different times. Poor horses can rarely have a quiet Easter. But this year it did happen. And the last evening, quite unexpectedly, about all the people of Cluj who have had a major role in the city rising to European fame were sitting around that table in the Casa Boema. Then, for a moment, it became clearly visible what the myth of the city was based on. The myth, which, like all media myths, are either misconstructions or are not, but are certainly attempts at narratives about what still makes things happen in Eastern Central Europe, while neither history, nor the current political situation are favourable to anyone who gets the idea to create something in this part of Europe. And then, here is a city that proves all that wrong, mostly by presenting an incredible number of art people who think and act. A hub, a nerve centre, bringing together people, ideas, determination and action. Here, people’s determination can change “the twelfth of Never” into “the twelfth of Now.”

Translated from Hungarian by Zsolt Kozma.

Gergely’s residency in Cluj was made possible with the support of AFCN and the Balassi Institute.

POSTED BY

Gergely Nagy

Gergely Nagy (b. 1969) is a journalist, editor and author who lives and works in Budapest. Currently he is the editor in chief of Artportal contemporary art website. His main fields of interest are cu...

artportal.hu/

Comments are closed here.