Last May, in Timișoara, and last June, in Prague, took place “A Spring of Hope, A Winter of Despair”, an exhibition that proposes a different perspective on the conceptual art of the ‘70s and ‘80s in Romania and the former Czechoslovakia, together with more recent artworks that outline a new way of understanding the relationship between the artistic preoccupations of the time and more current perspectives. Bringing together renowned artists from both countries, the exhibition title is taken from the opening quote of Charles Dickens’ historical novel A Tale of Two Cities, suggesting a dialog between artworks born, on the one hand, from the political tensions of the Iron Curtain and, on the other, from the purely human desire for a subjective aesthetic experience.

Far from being a recovery or an historical exhibition, “A Spring of Hope” aims to be a trans-historical, non-linear experience with a particular rhythm. The art produced in the communist regimes of these two regions varies according to each’s specific relationship to Moscow and their distinct negotiations over its policies, both in the case of “official art” and “underground” art. A distant glance would suggest that this body of work is consistent throughout the Soviet bloc, but Western modernist influences were most felt in Czechoslovakia, on the edge of the Iron Curtain, where in the 1960s artists had been in contact with Actionism and Fluxus and experimenting with performance art and radical happenings. In Romania, we encounter artists engaging with both official and alternative art in secret, spurred on by the “liberal thaw” that seemed to be taking hold.

The political deterioration that characterized this period resulted in some of the most acclaimed works of conceptual art, created out of perseverance and a desire to experiment with whatever medium available. The demands and restrictions of official art, the gradual disappearance of private property and the ever-changing public space forced artists to investigate intimate themes and concepts centered around the body: the apolitical body, the body as measure, the relationship with nature. The wave of performance art at the time captured the imagination of artists, who approached it not for the public, like in the West, but for the photo or video camera, for documentation. These “documents” were exhibited in “A Spring of Hope” in the form of testimonies without the consciousness of a future, of intimate explorations, beyond ideology, which are still present today in the work of artists born later, such as Gabriela Mateescu or Delia Popa.

A black wall, with the word Horizon in white – Jiří Valoch’s site-specific text intervention – reinforces the atmosphere of urgency in which the conceptualism of the 1970s-80s was formed – the need to capture the present moment, to convey a message using whatever means available, unaware that these “snapshots”, sometimes on precarious video format, sometimes on precious argentic photography, would benefit from today’s visibility. Unlike “Western” art, which Milan Knížák, one of the first Czechoslovakian artists to engage with Fluxus-like happenings, described as trivial, without stakes, the “underground” art of the period was a necessity, not so much ideological, but a fundamental need to fuse art and life.

The exhibition is based on these historical foundations, to which are added multiple layers of meanings, which interweave both stylistically and conceptually through a unifying visual coherence. The human body is present in almost all of the works on display as a central nerve, from which various paths of relation emerge, emphasized by the proximity of the works. The small, archival photographs, a majority within the exhibition, are occasionally broken up by large video monitors or projections, reinforcing the idea that the themes and concepts addressed do not necessarily belong to a particular generation, but are constantly revisited and reinterpreted.

The social body was a major preoccupation under communism in both countries, and in Czechoslovakia the radical wave of Czech Actionism, characterized by experimental forms of performance art in unconventional areas, thus outside traditional art spaces, gained momentum. Motivated by political constraints, artists often chose the public space to exercise their freedom of expression through small, often imperceptible gestures full of candor and depth. We see Jiří Kovanda in photographs where he opens his arms wide in a crowded Prague square, welcoming people to pass him by (November 19th, 1976), or positioned on an escalator facing others in an attempt to open himself, become vulnerable and connect with strangers (Untitled [On an escalator… turning around, I look into the eyes of the person standing behind me…], 1977) Similarly, Decebal Scriba, with his [The] Gift (1974), is photographically documented walking through the streets holding an immaterial object in his hands, ignored by passers-by. In these works, one can discern a burning, yet unbridled, desire to connect authentically with fellow human beings. What’s more, the juxtaposition of the artists gives the impression that the works belong to one person: the two resemble each other not only in gestures, but also in the hair and beard worn in the style of their respective years.

During the event in Prague, they met for the first time and resumed these considerations, together with Marilena Preda Sânc and Vladimír Havlík, and contemplated on the past through the lens of the present, especially since both Kovanda and Scriba have remade their actions in 2007 and 2017, respectively, also present in the exhibition. The discussion touched on both the nostalgic and ironic aspects of conceptual art of the ‘70s and ‘80s. This is perhaps best seen in Gheorghe Rasovszky’s documented actions in the public space but also in his later work, which touches on other important aspects in the exhibition. In Leaving Home (1979), we see the artist literally climbing the walls – an instinctual need to escape, if not physically, then perhaps into the realm of dreams (Me Dreaming, 1988), sleeping on a bench in the public space and then measuring his dream between his palms.

Vladimír Havlík also appears to be sleeping in Attempt to Sleep, not in a city but in nature, an apolitical space of freedom. The artist wraps himself in the rich, grassy soil in an attempt to fully merge with nature. He has also addressed the lack of greenery in urban areas with the work Trial Flower (1981), in which he plants a daffodil instead of paving – the same kind of minimal intervention typical of his compatriots, yet highly significant. This communion with the elements is even more evident in his later series Winter Pieces from 2013, in which a hand showing the victory sign sprouts from a snow-covered clump of wood, revealing that even today, nature is the most successful escape from an equally troubling everyday. In A Controlled Fall (1981), Havlík photographically documents his fall from a snowy hill, an action that hurts the body but not the environment, as the snow remains undisturbed by the artist’s impact, suggesting its resilience in the face of any oppressive regime. Similarly, Delia Popa presents a video self-portrait in which she repeatedly collapses next to her grandfather’s walnut tree (Self-Portrait as a Falling Tree, 2023), a commentary on the massive deforestation undertaken by Ilfov County Council. In her view, nature cannot cope with the demands of capitalism.

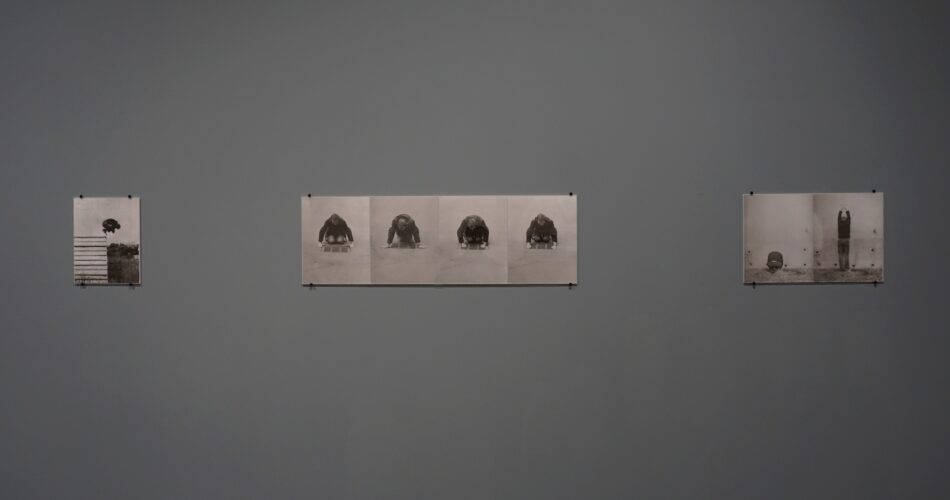

More than just a refuge, nature also represents a place for existential contemplation that can offer countless possibilities: of dreaming, of silence, of love, etc. (Observation of Landscape I series, 1974). According to Jiří Valoch, an artist and theorist inspired by linguistics and semantics, nature has its own language that can only be understood through total immersion in it, only if the body lets go of the ego and becomes one with the environment. Karel Miler adopts these views in the key of Zen Buddhism, which he has been practicing since the 1960s. Thus, in his series Either-or (1972), Limits (1973), Grating (1974) and Felt by the fresh grass (1976), the artist chooses to totally immerse himself in both the public and the natural space, measuring areas with his body, outlining a semantic poetry and a new way of relating to reality. Scriba has also experimented with body postures as a sign and a way of exploring and understanding the world, in works such as Unfolding (1982), from the Body sign series. From a defensive crouching position, the artist’s body uncoils and rises skyward; he appears stranded on the seashore (The Failure, 1982), a gesture of abandonment contrasted by his victorious arms emerging from the sea (Nothing About Drowning, 1985). Beyond the symbolism of these actions, the aesthetic quality of the works is indisputable. The body as a sign and the sign on the body – the exhibition takes a turn from the body liberated by nature to the body constrained by the restrictions of the regime. This political dimension is strongly felt in the series Mask 2 (1976), in which Scriba’s face is tightly bound with a string that leaves visible marks on his skin.

Iulian Mereuță also tackles the theme of the bound self in Captured (1970), which reveals his interest in processualism and experimental photography. The work is the result of an eight-hour performance in his studio in Bucharest – an action almost foreshadowing the seizure of his workspace after the artist emigrated to France. Here, the body is pushed to its limits, subjected to tensions hard to imagine, just as aesthetics itself is subjugated by the canons of official art. Captured is put in direct dialog with the works in Marilena Preda Sânc’s series My Body is Space in Space, Time in Time and the Memory of All (1983), where the same bound body becomes female, this time made vulnerable by interventions in ink over photographs. In this case, the imposed creative act constrains and censors the artist’s body, revealing the way feminine corporeality was represented in the visual arts at the time. The artist confesses that it was only through mail art that she was able to send her work abroad to be seen.

The exhibition “A Spring of Hope” also presents, as mentioned, more recent approaches to society’s impact on the body. Eva Koťátkova’s 46-minute film, Stomach of the World (2017) is an exploration of the body in relation to the world through ingestion and transformation. If in communism the body was consumed, bound, minimized, in capitalism the body consumes, grows, becomes a monster: the world is seen through the eyes of children who playfully explore what the self is and how it is influenced by both external and internal factors. The movie begins in a classroom, with drawing and physical exercises, slowly evolving into imaginative games and visual metaphors for consumerist society, illustrated in the final moments when the children appear hanging upside down near a landfill. The same bodily experiments of testing limits and questioning the self in relation to the environment discussed earlier can also be seen in recent Czech art.

If the artists of the past wanted liberation – political, artistic, spiritual, of movement – how do they relate to present realities now? Rasovszky ironically responds to the new circumstances offered by the free flow of goods: he smiles contently against the ultra-colorful backdrops of flea markets in fields or graveyards. The future is here, but its color and brightness are artificial; the liberalization of aesthetics delivers us into a camp, self-referential zone. The same goes for Roxana Trestioreanu’s Madame de Récamier (2011), a self-portrait in a hotel lobby, lying on a sofa against a wallpaper of fluffy clouds. The photograph has a rococo, painterly quality, but the artist’s sharp gaze conveys that while she offers herself to be looked at, the viewer is also being looked at.

This performativity informs the works described above, but the exhibition also probes into the lived experiences of those outside the art world during the communist period, in relation to the present. The film My socialist home (2021) by Iulia Stătică and Adrian Câtu opens an important conversation about dwelling. The personal space is investigated through the lens of a documentary with various Bucharest residents who still live in their communist-era apartments. Their stories reveal varied perspectives on domesticity and its often unexpected and surprising evolution as the city changed, with a focus on the emblematic socialist blocks of the period. Irina Botea also emphasizes the utopian architecture of the communist regime in her It is Now a Matter of Learning Hope (2014). In this video work, artist Ileana Faur strives to memorize passages from the utopian theories of Marx, More, Flusser and others, with Morii Isle in the background, an unfinished communist architectural project.

Given that the dreams of the past have been dashed, does it still make sense to hope for a better future that has yet to come? Gabriela Mateescu looks to her father, who lives in precarious conditions in the countryside, for answers. In her video Nothing, nothing, nothing … Chronicles of Memory (2024), the artist diaristically documents her visits to her father and his stories from his youth. As the title suggests, it was marked by deprivation and shortcomings, administrative abuses and other facts systematically omitted from history, which we can only learn through word of mouth from our parents. Gabriela Mateescu’s work opens up a useful discussion about collective memory and forgetting, as well as the importance of recognizing and healing past traumas. The same concepts can be found in Kamila B. Richter and Michael Bielick’s interactive video installation Garden of Error and Decline. Constantly updated since 2010, the work uses real data from Twitter and the stock market to generate various narratives about current global disasters. It becomes apparent that there are parallel subjective realities and situations of privilege and precarity in both the past and the present, a problem exacerbated nowadays by social media networks, with a profound impact on our perception of the world.

In conclusion, the exhibition of “A Spring of Hope” succeeds in a coherent multi-layered discourse about a possible universal aesthetic of Eastern Europe in the 1970s-1980s, while pointing out the subtle but significant differences in engagement with everyday life. It is one of the few exhibitions that comparatively explores art from two European regions under the same oppressive political regime. The similarities and differences, the dialog created, the interplay between the multiple planes of meaning reveal an artistic rigor that is not a matter of form but of content. Despite the aesthetic and conceptual similarities, it becomes clear that there is no single overview of the communist period, because consciousness is also layered, as curator Olivia Nițiș observes.

The exhibition of “A Spring of Hope”, curated by Olivia Nițiș and produced by the Contrasens Cultural Association, took place in Timișoara, at FABER, during 11.05 – 30.05.2024 and in Prague, at the Pragovka Gallery, during 6.06 – 29.08.2024.

POSTED BY

Marina Oprea

Marina Oprea (b.1989) lives and works in Bucharest and is the current editor of the online edition of Revista ARTA. She graduated The National University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, with a background i...

marinaoprea.com

Comments are closed here.