The importance of Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957) in the history of contemporary art is already beyond justification, any study dedicated to 20th century art history can stand as testimony. A secondary and negative consequence of this “universality” is the Romanian nationalist ideology, which links his sculptures to an indefinite revelation of a Romanian essence (a “Romanian feeling of Being”), as if the “primitive” forms do not belong to a cultural geography with much older and larger sphere than the borders of the nation-state. In any case, an exhibition dedicated to this canonical artist involves an effort of coordination, expensive financial and security conditions, a process of ideological asepticism as well as a specific visibility conditioned by the modernist “aura” of his works.

According to Sanda Miller if we were to make an inventory of what Brâncuși left behind we would talk about 215 known sculptures, of which at least 40 – mainly from his early period – have disappeared or been destroyed, indexed thus only from photos. Added to these is a formidable photographic archive – 560 negatives and approximately 1250 original photographs, mostly priceless due to the disappearance of the negatives. The small number of sculptures is a consequence not only of the technique used (he will abandon modelling for carving), but especially of his artistic “personality” marked by reflexivity and perfectionism. It should be noted that by 1923 he would establish a “repertoire” of forms that would be repeated, with small variations, until his disappearance in 1957.[i] About photography, a little later.

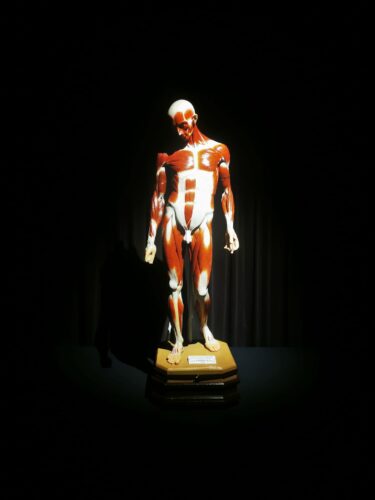

Some time ago I went to see the exhibition “BRÂNCUȘI: ROMANIAN SOURCES AND UNIVERSAL PERSPECTIVES” hosted by the National Museum of Art Timișoara (30.09.2023–28.01.2024). The curator Doina Lemny[ii] known for her research works dedicated to Brâncuși (as well as for her activity within the Centre Pompidou), proposes a diachronic reading of his oeuvre by inserting not only photographs, but also correspondence (which, unfortunately, cannot be understood, either because of the authors’ handwriting or because of the light, not being reproduced verbatim on an explanatory label); the exhibition consists in thematic separations that are marked by descriptive texts announcing what exactly you see and in which period of creation are made; video extracts from the recordings made by Brâncuși, part of the Pompidou Centre collection are also included, as well as a documentary film about the complex of works at Târgu Jiu (Monumental ensemble “Path of Heroes”) in the last room that closes the route. A successful propaedeutic exhibition that opens with the “Écorché” executed for pedagogical reasons, in 1901, in collaboration with Dr. Dimitrie Gerota and ends with the “Endless Column”. In short, you understand his artistic path and see the relevant sculptures (the exhibition gathers 100 pieces: 22 sculptures, 11 drawings, 44 photographs, but also a series of documents – the full list can be also found at the end of the official catalogue of the exhibition). Along with the connections of the curator the exhibition could not have been realized without the involvement of Ovidiu Șandor the president of the Art Encounters Foundation (appointed Commissioner of the exhibition).

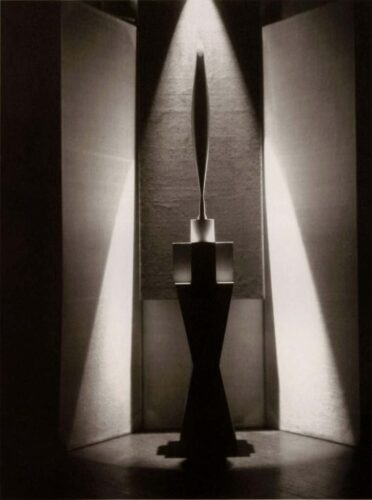

However, I left the Museum with some feelings of discontent for not being able to see the “paradigmatic” sculptures (Măiastra, Bird in Space, Fish[iii]) other than from the middle of the aisles (that can be so easily crowded) and from the front or side. I could not linger or patiently admire each work, the space being rather small and the scenography of visibility determined by the duo anthracite curtains – spotlights. I was also overcome with a slight claustrophobia; I didn’t understand why and what were the stakes, although I can understand the logic of the security measures and the need for “adaptation” to the Museum. There was no exhibition brochure, and the website offers no substantial information about the exhibition. We see the partners and financiers of this exhibition, but it seems somehow strange that exchanges based on image capital do not improve the reception of Brâncuși’s work by sponsoring some brochures or a catalogue of the exhibition at an affordable price (of course, other dimension and quality, maybe a digital version?). But coming back to what matters: I was able to discover the concept of the display only by looking on the internet for the press statements of Kim Attila, the architect of the exhibition, I quote: “The scenography here is inspired by Brâncuși. We see in his photographs that he liked to put draperies behind the works. We put this soft background, the vertical anthracite drapes and the carpet as well, to allow the viewer a moment of intimacy with the works. Only they are illuminated, our body and the sounds disappear and we remain in relationship with the special geometry of the sculptures.”[iv]

One can easily find studies (even first-hand) about Brâncuși ‘s relationship with photographic practice, as the cited one at the beginning of this text. More than keeping a photo archive of his sculptures in various stages of completion or of his atelier, from the very beginning Brâncuși was not satisfied with the photos taken, even if we are talking about important photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen or Man Ray[v]. Simply put: the dissatisfaction was related to the way his works could be received, considering that he would be the only one in a position to capture them according to their conception and intention. Although he used photography for documentation/archiving purposes and for potential buyers (collector John Quinn), it is only from 1921, when he asks Man Ray for „didactic” support, that we can speak of a real interest in “professionalizing” the captured image. To be able to indicate what exactly Brâncuși was looking for, we will compare some photos. [vi]

Bird in Space, 1925, photo: Edward Steichen,

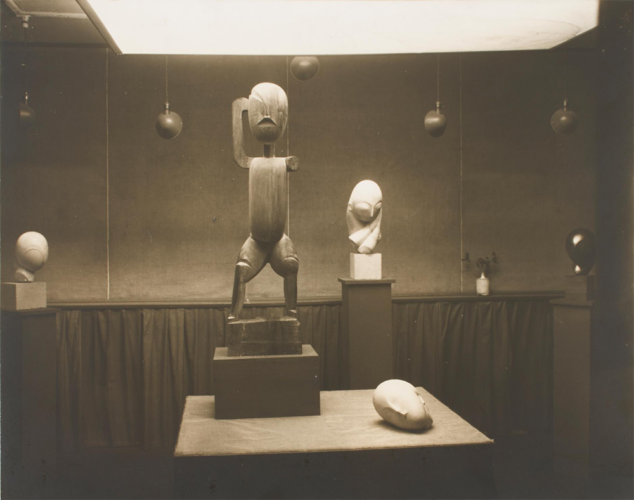

View from the “Brancusi” exhibition, 1914, Gallery 291 in New York, photo: Alfred Stieglitz

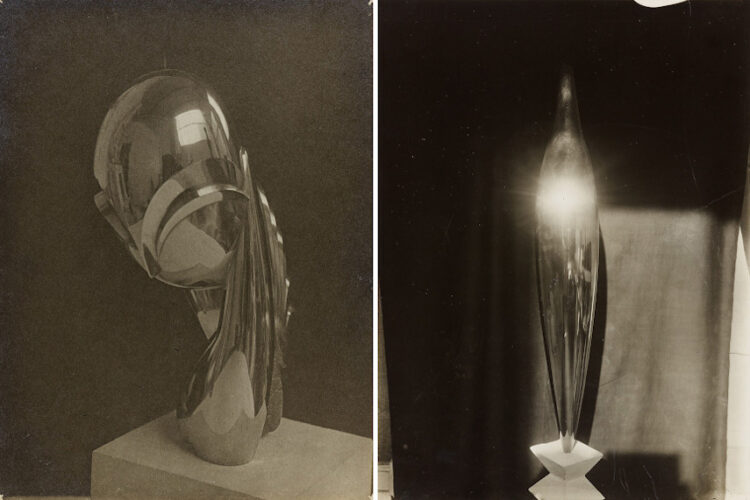

Left – Mlle Pogany II, 1920; Right – Golden Bird, 1919.

Sleeping muse, The Cock, 1924

Princess X, 1930

Bird in Space, polished bronze, 1928

Bird in Space, white marble, 1927

The difference between the first two pictures and Brâncuși’s seems obvious: the form is constantly pushed to ricochet as if the “essential” qualities are only indicated and equally separated within our gaze; the images do not aim to be formally successful but to ground the potentiality of their “representational” content. They inaugurate a route of reflection that adds content as one returns to the understanding of their sculptural proposal; meaning emerges between the interspersed relationships of light and dark or shadows and the descriptive limit of their names, “organic supplement” of a material stasis capturing a singular mood or event (in-air, in-sleep, in-water). The photos do not just fix a spatial arrangement, but above all a qualitative “disposition”, a speculative device for how to gaze. Princess X is only through/in shadow a feminine posture, the work on the other hand is a phallic “mystery” (along with Youth Torso).

Of course, the explanations can also go along the lines of his „origin” (affinities) of which he was proud, or the interest in folklore (along with the inquisitiveness of the Parisian avant-garde in the “primitive” art of whose influence he was not spared) which can be found in the subtle translations of his sculptural symbolizations: the bird or the fish captured in their environment of becoming – braked in relation to a modern knowledge – captured in the differential “nature” of their movement. The sculptures maintain this “primordial” fascination with what traverses the air, the earth or the waters, it remains to know how to look at them.

A new sculptural logic seems to be put into play, “the form becoming a manifestation of the surface”, as argued by Rossalind E. Krauss following the route by which Brâncuși forsakes a “classic” sculptural manner – structured by separate elements, articulated and connected axially to each other, intimately determined by an internal “armature” to expressivity – to establish a qualitatively unitary composition which can no longer be analysed fragmentarily (relations between the parts) and which conveys viewing in contemplation: the series Suffering (1907) – Prometheus (1911) – New Born (1915) – Beginning of the World (1920) or the series Măiastra (1910) – Golden Bird (1919) – Bird in Space (1923).[vii]

I liked the intention of the exhibition, i.e. to conceptually distinguish the contribution of photography in the strategy of arranging Brâncuși’s sculptures, to give them a well-deserved place in the visiting route (although here, too, in some cases the lights did not help to much) and to somehow put them to work not just as strictly documentary material. There is a problem, however, with the simple retention of the setup “vertical anthracite curtains with spots” that lit from above and equally regardless of the materiality and particularity of the sculptures. It would perhaps have been a plus if the exhibition took up the indicative requirements of Brâncusi’s photos finding solutions to fully reproduce the singularity of the selected sculptures.

* This journalistic material was produced with the support of an Energie! Creative Grant awarded by the Municipality of Timișoara, through the Centre for Projects, within the Power Station component of the National Cultural Program “Timișoara – European Capital of Culture in the year 2023”.

The material does not necessarily represent the position of the Centre for Projects and the latter is not responsible for its content or how it may be used.

[i] Art Since 1900. Modernism Antimodernism Postmodernism, ed. Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, David Joselit, Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Editura Thames & Hudson, third edition, 2016, pp 252-255;

[ii] For understanding the title of the exhibition see the official catalogue of the exhibition and its essay “BRANCUŞI. Wisdom of Earth – unique work” on the website https://biblioteca-digitala.ro

[iii] “Milestone” was brought from the Atelier Brâncusi of the Pompidou Center Paris, Măiastra, Danaida and Fish from the Tate, London, and Bird in Space from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection Venice.

[iv] https://romania.europalibera.org/a/s-a-deschis-br%C3%A2ncu%C8%99i-toate-drumurile-duc-spre-muzeul-na%C8%9Bional-de-art%C4%83-timi%C8%99oara/32618217.html

[v] For more details about Brâncusi’s atelier and his relationship with photography as a medium for exhibiting his sculptures – Man Ray, Self Portrait, Editura McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1963, pp. 206–213; https://monoskop.org/images/6/62/Man_Ray_Self_Portrait.pdf

[vi] A better view of the reproductions – https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.35504.html, also https://www.dappledthings.org/deep-down-things/17028/how-putting-brancusis-bird-in-space-on-trial-changed-our-societys-definition-of-art ; –https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/cRbkRk, also https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/galerie-gmurzynska-constantin-brancusi. See the marble variant of Bird in Space – https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/ressources/oeuvre/cApGqy ; – https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/galerie-gmurzynska-constantin-brancusi

[vii] Rossalind E. Krauss, Passages in Modern Sculpture, MIT Press, 1981, pp 84-104.

POSTED BY

Emilian Mărgărit

Emilian Mărgărit is an independent curator and since 2017 founding member of Image and Sound, Bucharest. He has a PhD in Philosophy (contemporary French Philosophy), he has published in collective v...

Comments are closed here.